It is Saturday, 1 November 2014. I am book-browsing at Barnes and Noble on Fifth Avenue in New York City when my attention is caught by a collection of beautifully produced volumes. I look closer and realise that these books are part of what’s called the Leatherbound Classic series. An assistant informs me that these fine specimens help to ‘embellish your book collection’. Since this exchange, I am reminded time and again that, as symbols of cultural refinement, books really matter. And, though we are meant to be living in a digital age, the symbolic significance of the book continues to enjoy cultural valuation. That is why, often when I do a television interview at home or in my university office, I am asked to stand in front of my bookshelf and pretend to be reading one of the texts.

Since the invention of the cuneiform system of writing in Mesopotamia around 3500 BCE and of hieroglyphics in Egypt around 3150 BCE, the serious reader of texts has enjoyed cultural acclamation. The clay tablets on which marks and signs were inscribed were regarded as precious and sometimes sacred artefacts. The ability to decipher and interpret the symbols and signs was seen as an extraordinary accomplishment. Egyptian hieroglyphics were thought to possess magical powers and, to this day, many readers regard books as a medium for gaining a spiritual experience. Since text possesses so much symbolic significance, how people read and what they read is widely perceived as an important feature of their identity. Reading has always been a marker of character, which is why people throughout history have invested considerable cultural and emotional resources in cultivating identities as lovers of books.

In ancient Mesopotamia, where only a small group of scribes could decipher the cuneiform tablets, the interpreter of signs enjoyed tremendous prestige. It is at this point in time that we have one of the earliest hints of the symbolic power and privilege enjoyed by the reader. Through limiting access to their magical knowledge, ambitious scribes protected their cultural authority as readers jealously.

In the seventh century BCE, when the Old Testament’s book of Deuteronomy was written under the sponsorship of King Josiah in Jerusalem, the high bar was set for veneration of the book. Josiah used the scrolls written by his ‘deuteronomists’ to solidify a covenant between the Jewish people and God – and, in an inspired act of political strategy, to legitimise his legacy and claim to the land.

In Roman times, starting in the second century BCE, books were brought down from heaven to earth, where they served as luxury goods that endowed their wealthy owners with cultural prestige. The Roman philosopher Seneca, who lived in the first century, directed his sarcasm at the fetish for grandiose display of texts, complaining that ‘many people without a school education use books not as tools for study but as decorations for the dining room’. Of the flamboyant collector of scrolls, he wrote that ‘you can see the complete works of orators and historians on shelves up to the ceiling, because like bathrooms, a library has become an essential ornament of a rich house’.

Seneca’s hostility towards the ostentatious book collector was probably influenced by his aversion towards the public reading ‘mania’ that appeared to afflict the early Roman Empire. This period saw the emergence of the recitatio: public literary readings conducted by authors and poets that many wealthy citizens regarded as an opportunity for self-promotion. Seneca looked on these vulgar performances of literary conceit with contempt, and he wasn’t alone. Readings by self-important and vain individuals in Rome and other parts of the Empire became a target for sarcastic humour. Many leading Roman writers and satirists, from Horace (65 BCE-8 BCE) and Petronius (27 CE-66 CE) to Persius (34-62) and Juvenal (55/60-127), directed their wit at the ostentatious display of public readings.

According to the Roman satirist Martial, not even public toilets were off-limits for intrusive public-readers. In one of his sarcastic epigrams, he wrote:

You read to me as I stand, you read to me as I sit,

You read to me as I run, you read to me as I shit.

I flee to the baths; you boom in my ear.

I head for the pool, you won’t let me swim.

I hurry to dinner, you stop me in my tracks.

I arrive at the meal, your words make me gag.

The satirists who mocked the recitatio understood that a reputation for refined reading represented an important source of cultural capital. The sharp wit they directed at their targets can be seen as a form of literary policing. Petronius’s ridicule of Eumolpus the ‘tiresome enthusiast of poetic recitation’ in his Satyrica can also be read as an example of the policing of taste. Not for nothing was Petronius described by his contemporaries as the arbiter elegantiarum – judge of elegance in the court of the Roman Emperor Nero.

After the fall of the Roman Empire in the fifth century, Europeans who possessed material wealth but lacked the elegance and sophistication of their noble social superiors created private libraries to gain a reputation for refinement. Indeed, for many, the possession of a well-stocked library was an end unto itself. Almost 1,000 years later, with the advent of the Renaissance and the rise of commerce and trade, ownership of books had expanded and the cultural distinction bestowed by reading fell to more people still. Geoffrey Chaucer in his poem The Legend of Good Women, written in the 1380s, exemplified this trend by declaring that he held books ‘in reverence’.

By the 14th and 15th centuries, the pretentious, pompous reader had emerged in full force. Richard de Bury’s essay Philobiblon, written in 1345 but published only in 1473, is said to be the ‘earliest English treatise on the delights of literature’. But Philobiblon says very little about de Bury’s actual experience of reading. He was a classical book fetishist whose real interest was collecting books rather than their study.

His biographer William de Chambre claimed that books surrounded de Bury in all of his residences and that ‘so many books lay about his bed-chamber, that it was hardly possible to stand or move without treading upon them’. De Bury must have anticipated that his avaricious appetite for collecting books could become a target of criticism and sarcasm, for he explicitly defends himself from the charge of excess in the Prologue to Philobiblon, declaring that his ‘ecstatic love’ for books led him to abandon ‘all thoughts of other earthly things’. The purpose of writing Philobiblon was to let posterity understand his intent and ‘for ever stop the perverse tongues of gossipers’; he hoped that his account of his passion would ‘clear the love we have had for books from the charge of excess’.

the portrait artist, seduced by the book’s spiritual and intellectual properties, continued to embrace it as an essential artistic prop

But the German humanist theologian Sebastian Brant didn’t get the message, at all. His satire Ship of Fools (1494) portrays 112 different types of fool. And the first one to climb aboard the ship was the Bookish Fool, who collected books and read for effect. Brant has him say:

If on this ship I’m number one

For special reasons that was done,

Yes, I’m the first one here you see

Because I like my library.

Of splendid books I own no end,

But few that I can comprehend;

I cherish books of various ages

And keep the flies from off the pages.

Where art and science be professed

I say: At home I’m happiest,

I’m never better satisfied

Than when my books are by my side.

Brant’s satire became a bestseller and was swiftly translated from German into Latin, French and English. But book lovers – fools and otherwise – could not be deterred. By the 16th century, a secular idealisation of the ‘love of reading’ had truly taken hold. Reading came to be regarded as a medium for self-discovery and for gaining spiritual insights into the ways of the world.

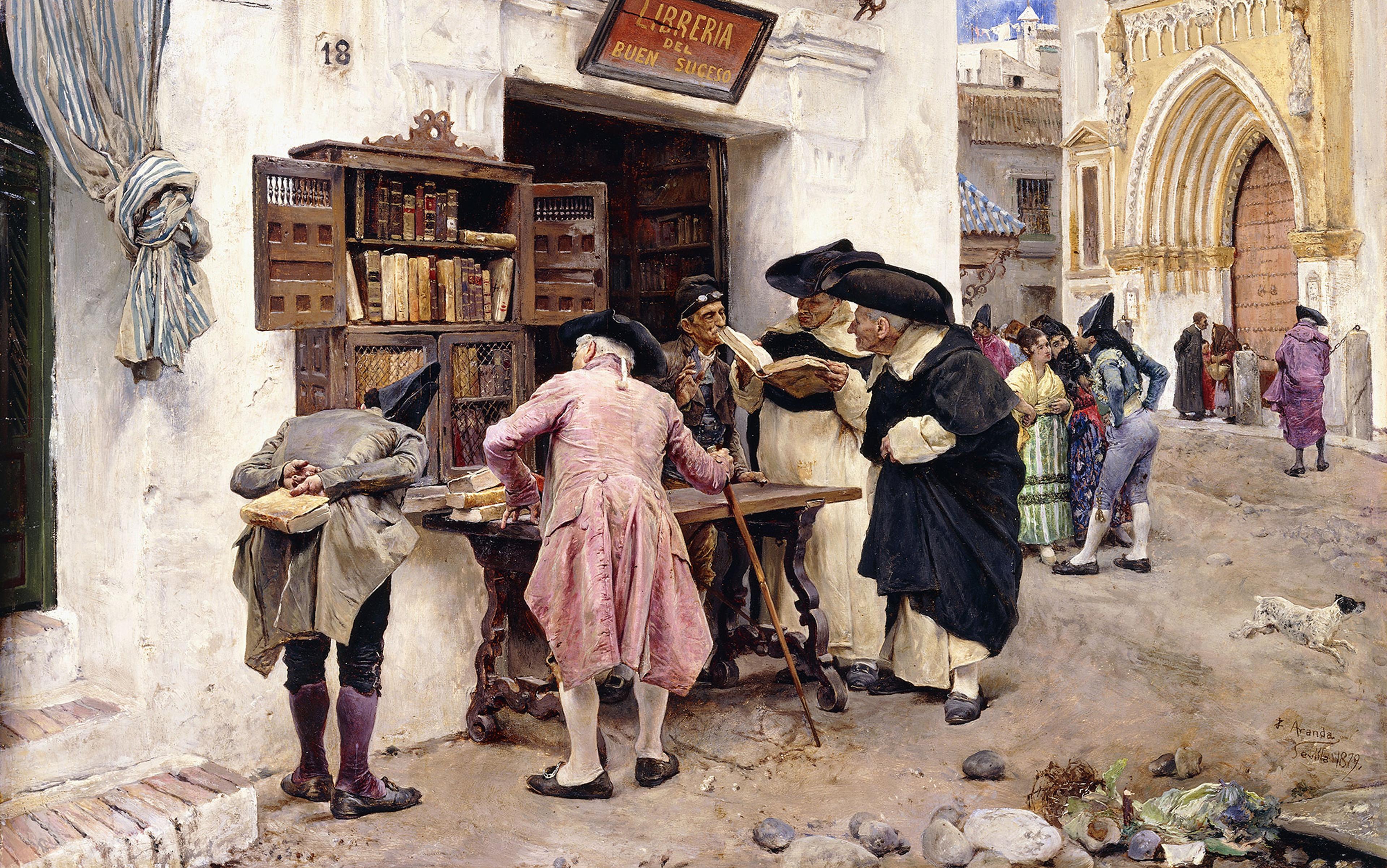

The symbol of reading was, perhaps, bigger than the act of reading itself. Individuals sought to capture their devotion to books through painted portraits that depicted them deeply absorbed in reading a text. Paintings of people reading and portraits of individuals embracing a book became widespread in Renaissance art. The manuscripts of this era are ‘inundated with images not just of books, but of people reading the books’, as Laura Amtower writes in Engaging Words: The Culture of Reading in the Middle Ages (2000).

During the centuries to follow, the portrait artist, seduced by the book’s spiritual and intellectual properties, continued to embrace it as an essential artistic prop. Paintings of the humanist poet Dante invariably depict him reading. A painting by the 16th-century artist Agnolo Bronzino – entitled Allegorical Portrait of Dante – depicts the poet holding open a very large edition of the Paradiso. The portrait is as much about the book as it is about Dante. Watching Dante’s performance of reading reminds the viewer of this man’s status as culturally accomplished and spiritually advanced.

With the 18th-century expansion of reading among the populace, the intelligentsia went out of its way to reinforce its superior status by emphasising the distinction between itself and lesser readers. By now, the literary critic had displaced the Roman satirist, praising accomplished readers as ‘men of letters’ while their moral opposites were characterised as ‘unlettered’.

‘To read is not a virtue; but to read well is an art, and an art that only the born reader can acquire,’ the novelist Edith Wharton insisted in her essay ‘The Vice of Reading’ (1903). Wharton wrote that the ‘mechanical reader’ lacked ‘innate aptitude’ and the ‘gift of reading’, and could never acquire the art.

By the 20th century, reading had been elevated into an art form, with intellectuals drawing a line in the sand. On one side was the so-called pretend reader and on the other – the elite. Even the novelist Virginia Woolf piled in. In her essay ‘The Common Reader’ (1925), she described the average reader as someone ‘worse educated’ than a critic, an individual ‘nature has not gifted’ so ‘generously’ as his more accomplished counterpart. According to Woolf, the common reader is ‘hasty, inaccurate, and superficial’ and of course ‘his deficiencies as a critic are too obvious to be pointed out’. The perspective stuck: readers continue to be classified and judged to this day. In The Pleasures of Reading (2011), the literary critic Alan Jacobs dared to differentiate between the vaunted readers and the lowly ‘people who read’.

In fact, the act has become so prestigious that reading to a child signifies parental competence, at a minimum, and moral and cultural superiority, at best. A parent reading to a child in a public space is making a declaration to the world – and so lofty is the activity that mothers and fathers now devote considerable time and resources towards encouraging children to physically embrace the book. It is not uncommon to see a toddler perched in a child seat in a car holding and looking at a little book.

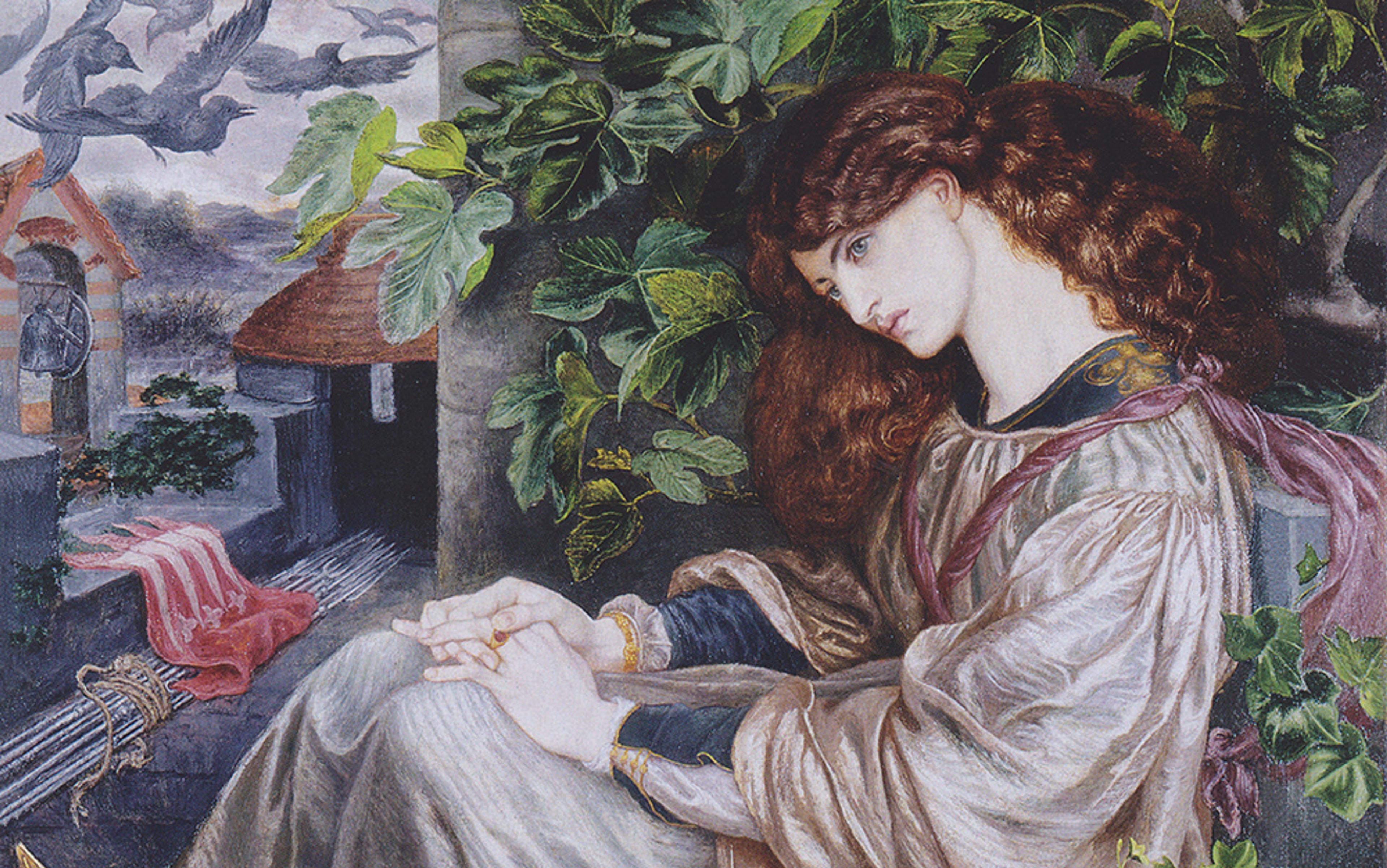

The contrast between an 18th-century woman reading a book and a teenager gazing at her smartphone illustrates the different ways we construct identity through reading

Before too long, these 21st-century toddlers might abandon the showy display of reading a book in public and adopt the habit of regularly checking their smartphones. If Seneca or Martial were around today, they would probably write sarcastic epigrams about the very public exhibition of reading text messages and in-your-face displays of texting. Digital reading, like the perusing of ancient scrolls, constitutes an important statement about who we are. Like the public readers of Martial’s Rome, the avid readers of text messages and other forms of social media appear to be everywhere. Though in both cases the performers of reading are tirelessly constructing their self-image, the identity they aspire to establish is very different. Young people sitting in a bar checking their phones for texts are not making a statement about their refined literary status. They are signalling that they are connected and – most importantly – that their attention is in constant demand.

With the rise of digital technology, the performance of reading has altered. The contrast between a woman absorbed in reading a book in an 18th-century portrait and a teenager self-consciously gazing at her smartphone illustrates the different ways that individuals construct their identity through reading. Today, the sophisticated consumer of digital text competes for cultural affirmation with the reader of physical books, but which performance of reading ought to be valued most?

For those who want to announce their intellect to the world, the choice should be clear: digital texts do not serve as markers for cultural distinction. Perhaps that is why, despite the widespread usage of tablets, sales of paper books have increased recently. Unlike books, tablets do not offer a medium for demonstrating taste and refinement. That is why interior decorators use shelves of books to create an impression of elegance and refinement in the room. Businesses actively promote the appearance of sophistication by offering ready-made libraries to consumers interested in acquiring the appearance of taste. One online company, Books by the Foot, offers to ‘curate a library that matches both your personality and your space’, promising to provide books ‘based on colour, binding, subject, size, height, and more to create a collection that looks great’. An online business that thrives on selling customised libraries indicates that, even in the digital age, the bookcase symbolises high culture.

The Bookish Fools are still with us, but fortunately many readers are not simply interested in the performance. They still lose themselves in the text and actually fall in love with the stories they read. Regardless of medium, what matters is the very human aspiration to embark on this voyage. It’s not the performance, and not the optics that really matter, but the experience of the journey to the unknown.