‘How-to writers are to other writers as frogs are to mammals; they are not born, they are spawned.’ So jeered the influential New Yorker journalist Dwight Macdonald in a 1954 screed against the self-help guides he worried were taking over the culture. Macdonald voiced the prevailing view that the distinct spheres – or species – of literary author and self-help writer had little, if anything, in common. Serious authors create; self-help writers multiply. But the influence of self-help on prestigious literature is much deeper and more sustained than figures such as Macdonald would have us believe.

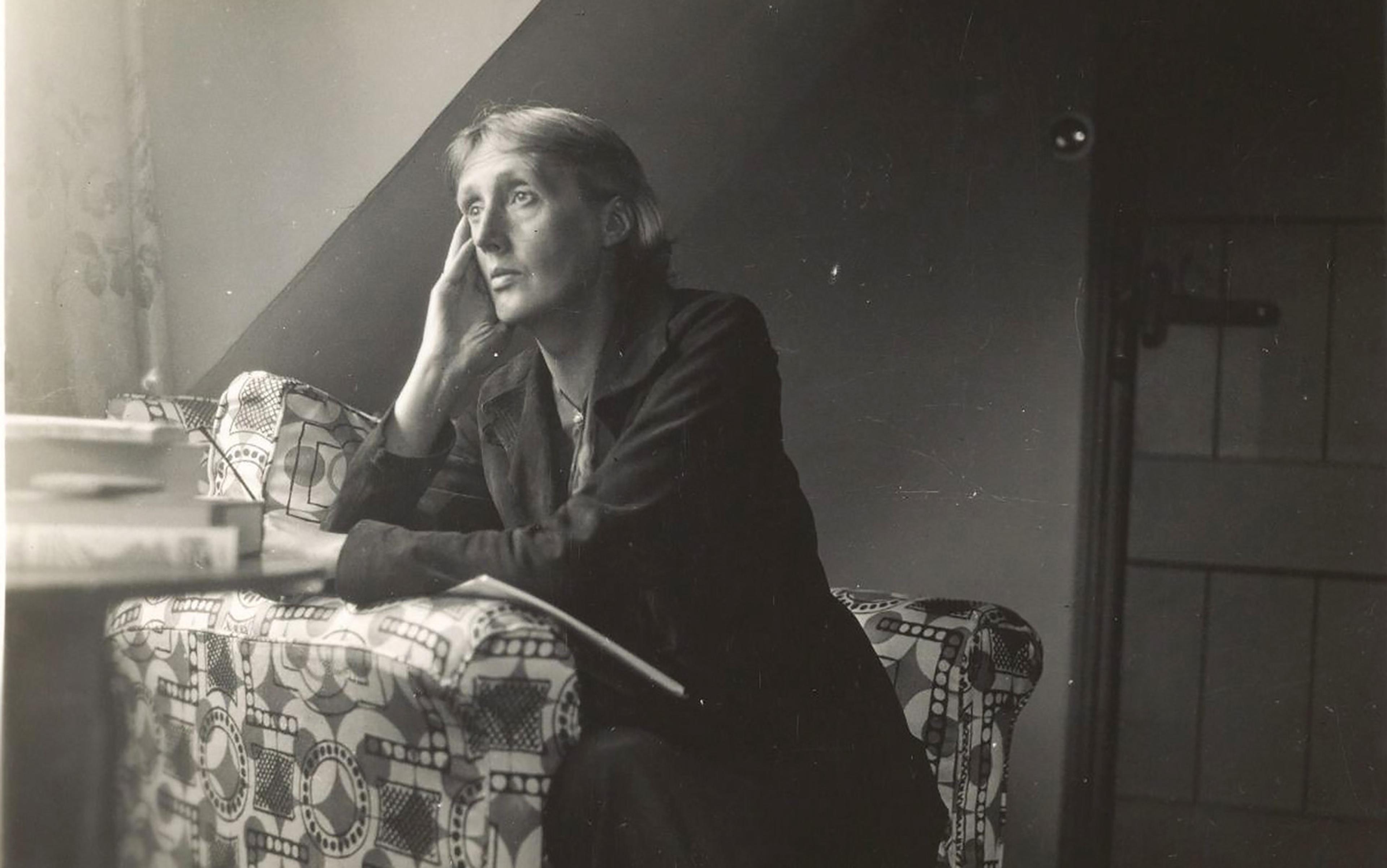

With the rise of the 20th century, literary authors had a new book genre to reckon with. It might seem anachronistic to picture the French symbolist poet Charles Baudelaire bingeing on ‘how to get rich quick’ books in 1864, or to imagine the late-Victorian aesthete Gustave Flaubert annotating a do-it-yourself manual, or to conceive of the ethereal modernist Virginia Woolf becoming so inflamed by Arnold Bennett’s practical guide How to Live on 24 Hours a Day (1908) that she writes her own time-books Mrs Dalloway (1925) and The Years (1937) in response. But this seems surprising to us only because most scholars – particularly literary scholars – have been so busy ignoring or dismissing self-help that they have failed to recognise its long history and tremendous impact on even the most prestigious literary authors. These authors often made fun of self-help, deriding its crass instrumentalism but also, and more surprising, they learned from its appeal, borrowed its techniques, and coveted its cultural influence.

As firmly canonised literary figures, Baudelaire, Flaubert and Woolf might have won the culture wars, but we are living in self-help’s world. A formidable force in the publishing ecosystem, the self-improvement market in the United States will be worth $13.2 billion dollars by 2022, according to Market Research. And though it is difficult to obtain exact figures due to the different labels under which it is sold, self-help – whether in American or native form – is a bestselling genre in Latin America, China, Africa, the global South, the Middle East – in short, all over the world.

The industry’s international appeal dates back to the first blockbuster improvement manual: Samuel Smiles’s Self-Help (1859), which turned the term into a catchphrase, and described successful labourers, artists and inventors who had used industry and perseverance to improve their conditions. Critics disparaged it, according to Smiles, as a ‘eulogy of selfishness’, but he saw his manual as a tool for working-class inspiration and uplift. The book marshalled scores of aspiring autodidacts in early 20th-century Nigeria, Syria, Guatemala, Trinidad and Japan (it’s said that late-19th-century Japanese samurai lined up overnight to buy a copy of the manual). In a 1917 review, the American poet Ezra Pound dismissed such ‘improving literature’ – ‘Samuel Smiles’s Self-Help and the rest of it’ – likening it to a ‘virus’, and the English author H G Wells wrote a cautionary tale, ‘The Jilting of Jane’, about a young man whose reading of Self-Help goes to his head, inspiring him to abandon his fiancée and his principles in favour of a higher match.

In these early years of the industry, literary authors enjoyed ridiculing self-help, occasionally even borrowing from the rival profession’s methods, but it was rare for a literary author to also establish a career in self-help, or vice versa, with one notable exception. Bennett was one of the few respected Victorian novelists to also enjoy a robust career in self-help. Like Smiles, he attracted polarised responses among the literati of the day. Widely mocked for his prolific output, his prominent stutter and his predilection for yachts (he owned two), he took breaks from writing popular novels such as Clayhanger (1910) and Hilda Lessways (1911) to write his ‘pocket philosophies’: portable, commonsense guides on topics including Literary Taste: How to Form It (1909), Self and Self-Management: Essays About Existing (1918), and How to Make the Best of Life (1923). How to Live on 24 Hours a Day, his most commercially successful book, promised to turn its reader into a ‘millionaire of minutes’; Henry Ford bought 500 copies to pass out to his staff. Though aware of the risk that such practical writing posed to his serious reputation, Bennett proclaimed that his self-help books ‘brought me more letters of appreciation than all my other books put together’.

If many today have never heard of Bennett, it might be because he fatally provoked the ire of Woolf – or that ‘queen of the high-brows’, as he put it – after his ambivalent short review of her novel Jacob’s Room (1922). Bennett found it a ‘clever’ work but maintained that ‘the characters do not vitally survive in the mind’ and that ‘her books seriously lacked vitality’. His review hit a nerve. ‘I daresay it’s true … that I haven’t that “reality” gift,’ she conceded, and wondered: ‘Have I the power of conveying the true reality?’ Woolf found Bennett’s approach to reality equally insipid, remarking that: ‘He can make a book so well-constructed and solid in its craftsmanship that it is difficult for the most exacting of critics to see through what chink or crevice decay can creep in.’ And yet, despite Bennett’s elaborate narrative architecture, she concludes that: ‘Life escapes; and perhaps without life nothing else is worthwhile.’

Beyond a mere irritation, Bennett’s quibbles with Woolf ended up inspiring some of her most famous manifestos about the technique and uses of fiction. The resulting essays, including ‘Modern Fiction’ (1921) and ‘Mr Bennett and Mrs Brown’ (1924), have become some of our most useful documents for understanding the modernist project and the way in which it departed from Victorian predecessors. And they are also revealing of how serious authors of the period sought to distinguish themselves from self-help’s increasingly popular ‘middlebrow’ literature. As the scholar Samuel Hynes quipped in 1967: ‘For one paragraph of mixed praise and criticism of Jacob’s Room, Bennett had reaped six separate published attacks and one lecture.’

The ‘ordinary waking Arnold Bennett life’ of his self-help manuals became a catalyst for Woolf’s fiction

When Bennett finally met Woolf and her husband Leonard at a dinner party, all of Bloomsbury held its breath. ‘Both gloomy, these two,’ Bennett remarked. ‘But I liked them both in spite of their naughty treatment of me in the press.’ For their part, the Woolfs were a little less conciliatory; they afterwards mocked Bennett’s speech disability and remarked that his only conversational contribution was to lean across the table and stutter: ‘W-w-woolf d-d-does not l-l-like my novels.’ And yet, after Bennett died suddenly in 1931 after drinking a glass of water contaminated with typhoid, around the time of his dining with James Joyce and his wife Nora in Paris, Woolf’s antipathy softened. The typhoid incident made its way into Joyce’s novel Finnegans Wake (1939), which, as the scholar Tom Henthorne points out, makes explicit reference to the polluted water and to Bennett’s novel The Grand Babylon Hotel (1902) or, as Joyce puts it, ‘babylone the great-grandhotelled’.

Woolf was rattled by the news of Bennett’s unexpected demise. As she wrote:

Queer how one regrets the dispersal of anybody who seemed – as I say – genuine: who had direct contact with life – for he abused me; and I yet rather wished him to go on abusing me; and me abusing him.

Remarkably, Bennett’s ‘contact with life’, the quality that she had so vehemently maintained ‘escapes’ his materialist fiction, was now what she grieved. Woolf was still pondering the aesthetic limits and possibilities of Bennett’s pragmatic view of life in 1933, two years after his death, when she recorded in her planning notes for The Years (then called The Pargiters) her ambition to provide ‘intellectual argument in the form of art: I mean how give ordinary waking Arnold Bennett life the form of art ?’ We might be glad that Woolf did not possess the ‘reality gift’ in the way that Bennett understood it, for her mystical attention to the unsaid and invisible defines her enduring novelistic vision. Rather than a mere affront or impediment, however, the ‘ordinary waking Arnold Bennett life’ depicted in his self-help manuals became a catalyst for her fiction.

There are numerous other such fascinating cases of productive mutual abuse, as Woolf has it, between literature and self-help. For instance, the same years that Bennett was dashing off his tremendously popular guides, Ernest Hemingway, a seeming world away in Kansas City, was implementing the self-help guidance of his uncle, Alfred Tyler, whose manual he likely acquired in 1917, as a graduation present. Alfred T Hemingway’s How to Make Good, or Winning Your Largest Success: A Business Man’s Talks on Personal Proficiency and Commercial Character Building – the Only Success Insurance (1915) combined Christian ideals of martial courage and stoicism (also touted by Ernest’s father) with the commercial and business strategies of the new popular advice. Presenting itself as a guide to help young men ‘make good’ in the world, it offered a compendium of many of the prominent self-help theories of the day, referencing Horace Fletcher’s ‘mastication system’ (a dietary philosophy advocating the extreme chewing of food), William James’s treatise on habit, and the theory of ‘autosuggestion’, advanced by the now largely forgotten yet extremely influential French positive-thinking pioneer, Émile Coué.

As literary scholar Michelle Moore observes in her book, Chicago and the Making of American Modernism (2018), Ernest’s personal copy of Uncle Tyler’s self-help manual bears the inscription: ‘Ernest Miller Hemingway. From Alfred T Hemingway (Uncle Tyler) Kansas City, MO. June 1917.’ Though Ernest moved many times, subjecting his enormous book collection to a great deal of vicissitude, he managed to preserve this volume his entire life. Describing the ‘worn binding’, Moore notes, ‘The book wasn’t just a childhood treasure, more symbolic than read. He read it repeatedly and most likely read and consulted its advice through the early years of his career.’

Just as Bennett enquired ‘What is the object of reading unless something definite comes of it?’, the first page of Uncle Tyler’s manual contains the single instruction to ‘Read with a Purpose.’ Inside, the advice continues: ‘Look your man squarely in the eye.’ ‘If a thing is to be done, get about it, and do it.’ ‘Be straightforward. Do not try to fool yourself or other people.’ ‘Be honest from top to toe.’ ‘Be adaptable. Don’t dread the new.’ ‘Be quiet. Be a “good listener”.’ ‘Show the real quality of your manhood. Be willing to do the hard things.’ ‘Study men,’ for ‘often you will see in men the thing to be avoided in yourself as well as the thing to be emulated, and the one is as important as the other.’

Critics have long discussed how Hemingway’s work with The Kansas City Star (a job he acquired though Uncle Tyler’s contacts) shaped his writing philosophy, but for anyone even remotely familiar with Hemingway’s work, the parallels between his uncle’s self-help advice and Ernest’s writing philosophy are striking. Much of Hemingway’s work is a ‘study’ of men or of ‘manhood’, as his uncle recommends, and Alfred Tyler’s principles of self-discipline and economy of expression carried through to Hemingway’s minimalist aesthetic. While Uncle Tyler instructed young men to learn to ‘be a good listener’, Hemingway echoed: ‘Listen now. When people talk, listen completely.’ While Alfred Tyler touted the necessity of ‘top to toe’ honesty, Ernest repeatedly advised to ‘write straight honest prose on human beings’ and to ‘write the truest sentence that you know’, insisting that, in addition to ‘invention’, honesty was the other essential quality of a writer. And perhaps with his uncle’s titular goal of how to ‘make good’ in mind, Hemingway’s letters abound with references to the literary problem of how to ‘make it’: ‘I’m trying to do it so it will make it without your knowing it,’ and ‘the thing to do is work and learn to make it.’

‘He never understood that it was just writing as well as you can and finishing what you start’

The revelation of Ernest’s careful engagement with his uncle’s self-help manual also offers fresh insight into a cliché of Hemingway studies, that of the ‘Hemingway hero code’. In the 1950s, Philip Young, one of Hemingway’s most influential critics, argued that the author’s works all follow a ‘Hemingway code’ by promoting the principle of ‘grace under pressure’ and the values of honour, courage and control. Young claimed that this life philosophy is embodied in Hemingway’s fiction by a ‘code hero’ who upholds these principles for the younger protagonist of the stories to emulate. Young’s theory of a Hemingway hero acquired a great deal of traction in Hemingway criticism (that is, until antiwar sentiments arose during the Vietnam War, after which at least one article instructed people to ‘Throw Away Your Hemingway Codebook’), but little attention has been paid to the self-help origins of this instructional outlook – as well as of the ideals of manhood, brevity and character that Hemingway advocates.

In light of the tremendous influence of Hemingway’s writing advice on those coming after (he is ‘the father of many writers who today sneer at him,’ in Ralph Ellison’s view), his case makes particularly visible self-help’s neglected entanglement in the literary tradition. The influence of Alfred Tyler on Hemingway’s art shows that some of the most canonised techniques of ‘high’ literature did not spring from rarefied principles but from the same commitment to commonsense values of honesty, directness, attention, economy and discipline that one finds in practical literature. As Hemingway complained of F Scott Fitzgerald, ‘Scott took LITERATURE so solemnly. He never understood that it was just writing as well as you can and finishing what you start.’

Hemingway didn’t just borrow aesthetic ideals from Uncle Tyler’s manual – he also satirically emulated its instructional voice in some of his early Toronto Star editorials, such as the piece ‘Popular in Peace, Slacker in War’ (1920) written for Canadians who had never set foot on the battlefield but wanted to benefit from the cachet of having served. There Hemingway offers ‘Some hints to those Canadians who went to the States to work at munitions and are now getting 15 per cent on their United States money,’ such as to purchase a trenchcoat from a second-hand store, to learn to whistle the tune of ‘Mademoiselle from Armentiéres [sic]’ on the streetcar, and ‘When you are asked by a sweet young thing at a dance if you ever met Lieut Smithers, of the RAF, in France or if you happened to run into Maj MacSwear, of the CMR’s, merely say “No” in a distant tone.’ Here, the terse masculinity for which Hemingway is known emerges as a form of what Judith Butler calls ‘gender performance’. His engagements with the reputation-management advanced by self-help support the theory that Hemingway’s masculinity was always somewhat satirical, aware of its constructed and instrumental quality.

In one of the rare exceptions to literary scholarship’s self-help obliviousness, Edward Said – though seemingly unaware of Uncle Tyler’s manual – noticed an affinity between Ernest Hemingway’s writings and the technical orientation of self-help. In ‘How Not to Get Gored’ (1985), Said wrote that Hemingway ‘took pains to convert his style of living into knowledgeability’, contextualising his brand of ‘American expertise’ within the obsession with ‘how-to-ism’ rampant in US culture. Reviewing a posthumous volume of Hemingway’s works, Said saw them as evidence that literary interest in self-help had run its course: ‘What stands revealed here is the great problem of American writing: that the shock of recognition derived from knowledge and converted into how-to-ism can only occur once, cannot be sustained.’ But contrary to Said’s assertion, literary authors’ fascination with converting knowledge into instructional imperatives has only increased.

The unabated literary interest in self-help is manifest in the many narratives of the past decade that take the ‘howtoism’ that Macdonald derided as a structural premise, such as Sheila Heti’s How Should a Person Be? (2010), Charles Yu’s How to Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe (2010), Mohsin Hamid’s How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia (2013), Eleanor Davis’s How to Be Happy (2014) and Jesse Ball’s How to Set a Fire and Why (2016), with more emerging every week. Written by novelists from all over the world, such works testify to the global reach and increasing cultural legitimation of a genre whose very existence once seemed to pose a threat to the purity and integrity of serious art. Instead of upholding Macdonald’s hierarchical distinction between self-help and serious literature, contemporary authors affirm the overlap between the two worlds. The protagonist of the acclaimed Mexican novelist Brenda Lozano’s Loop (translated in 2019 by Annie McDermott) proudly proclaims: ‘I read all literature as self-help,’ while Hamid’s narrator declares that ‘all books, each and every book ever written, could be said to be offered to the reader as a form of self-help.’ Contemporary novelists don’t feel obliged to choose between a commitment to beauty and the desire to amass some useful words to live by.