At Wat Doi Kham, my local temple in Chiang Mai in Thailand, visitors come in their thousands every week. Bearing money and garlands of jasmine, the devotees prostrate themselves in front of a small Buddha statue, muttering solemn prayers and requesting their wishes be granted. Similar rituals are performed in Buddhist temples across Asia every day and, as at Wat Doi Kham, their focus is usually a mythic representation of the Buddha, sitting serenely in meditation, with a mysterious half-smile, withdrawn and aloof.

It is not just Buddhist temples in which the Buddha exists in an entirely mythic form. Buddhist scholars, bewildered by layers of legend as thick as clouds of incense, have mostly given up trying to understand the historical person. This might seem strange, given the ongoing relevance of the Buddha’s ideas and practices, most lately seen in the growing popularity of mindfulness meditation. As Western versions of Buddhism emerge, might space be made for the actual Buddha, a lost sage from ancient India? Might it be possible to separate myth from reality, and so bring the Buddha back into the contemporary conversation?

The legendary version of the Buddha’s life states that the Siddhattha Gotama was born as a prince of the Sakya tribe, and raised in the town of Kapilavatthu, several centuries before the Christian era. Living in luxurious seclusion, Siddhattha remained unaware of the difficulties of life, until a visit beyond the palace walls revealed four shocking sights: a sick man, an old man, a dead man and a holy man. The existential crisis this sparked led Siddhattha to renounce the world, in order to seek a spiritual solution to life. After six years of trying out various practices, including extreme asceticism, at the age of 35 Siddhattha attained spiritual realisation. Henceforth known as the ‘Buddha’ – which simply means ‘awakened’ – Siddhattha spent the rest of his life travelling around northern India and establishing a new religious order. He died at the age of 80.

Only the bare details of this account stand up to historical scrutiny. According to contemporary academic opinion, the Buddha lived in the 5th century BCE (c480-400 BCE). But the failure to identify Kapilavatthu implies that he was not a prince who lived in a grand palace. The most likely sites are the Nepalese site of Tilaurakot, an old market town about 10 km north of the Indian border, and the Indian district of Piprahwa, to the south of Tilaurakot and just over the Indian border. But the brick remains at both places are a few centuries later than the Buddha, which at least agrees with the oldest literary sources: according to the Pali canon – the only complete collection of Buddhist literature from ancient India – the Buddha’s world generally lacked bricks, and Kapilavatthu’s only building of note was a tribal ‘meeting hall’ (santhāgāra), an open-sided, thatched hut (sālā).

Since Siddhattha lived in a wooden house, he would not have spent his youth sequestered in a palace, unable to experience the painful facts of life. Indeed, in the Pali Mahāpadāna Sutta, one of the most important sources for early Buddhist myth, the story of the Buddha’s youth is attributed to the entirely mythical figure of the former Buddha Vipassī, said to have lived 91 aeons ago (an inconceivably long time). This text is not a reliable source for the life of Siddhattha Gotama; to build up a more reliable picture, we must consider older parts of the Pali canon. In none of these is the Buddha ever called Siddhattha. Indeed, since this word means ‘one who has fulfilled [siddha] his purpose [attha]’, it looks very much like a mythic title, and in fact is used in only late mythic texts such as the Pali Apadāna.

The early texts instead refer to the Buddha as ‘the ascetic Gotama’. While the Mahāpadāna Sutta states that ‘Gotama’ was the name of the Buddha’s family lineage, other evidence tells a different story. Most texts say that the Buddha’s family belonged to the lineage of the ‘Sun’ (ādicca), which agrees with the Buddha’s oft-repeated epithet ‘kinsman of the Sun’ (ādicca-bandhu). Since there is no reliable evidence that the Buddha’s family belonged to the Gotama lineage, and a mass of textual evidence against it, how are we to explain this name? It is likely that ‘Gotama’ was the Buddha’s personal name, just as the Sanskrit equivalent (Gautama) is a common personal name in modern India.

Other aspects of the myth must be stripped away. The Buddha’s father Suddhodana was probably not a king. In an early story, the Buddha remembers attaining a meditative state as a child, while sitting under a tree as his father worked nearby. Are we to imagine that the King of the Sakyas had to work his own fields? At the most, Suddhodana would have numbered among the Sakya chieftains. The death of the Buddha’s mother, Māyā, when giving birth to him serves no purpose as myth, and can therefore be accepted as fact, but no early evidence states that, prior to his religious career, Gotama had been married to a girl called Yasodharā. When the Buddha’s son Rāhula is mentioned, his mother is simply called ‘Rāhula’s mother’.

Bringing the reliable historical fragments together, and discarding mythic elaborations, a humbler picture of the Buddha emerges. Gotama was born into a small tribe, in a remote and unimportant town on the periphery of pre-imperial India. He lived in a world on the cusp of urbanisation, albeit one that still lacked money, writing and long-distance trade. More importantly, we might ask what happened to Gotama after he had been drawn into a counterculture of ascetics and philosophers, and especially after he had attained his ‘awakening’. The texts say that the Buddha achieved remarkable success as a teacher straight away, but this seems unlikely.

The Pali account of the Buddha’s ‘First Sermon’ claims that its five recipients immediately attained enlightenment. But other texts give reason to doubt this. Indeed, these disciples are hardly mentioned again in the textual record, and in fact the occasional appearance of some of them is not entirely flattering. One text tells the story of an encounter between the Buddha and Koṇḍañña, the most prominent of the first disciples. After a lengthy absence from the Buddha, Koṇḍañña acts like a supplicating devotee, not an enlightened Buddhist saint (arahant): he is said to prostrate himself on the ground, stroking and kissing the Buddha’s feet, all the while announcing: ‘I am Koṇḍañña, I am Koṇḍañña!’

Another prominent member of the group of five, called ‘Assaji’, is mentioned in a few more places. But one text records the occasion when he was ill and became upset because he could no longer attain meditative absorption. Just like the text on Koṇḍañña’s emotional reunion with the Buddha, Assaji is not depicted as an enlightened saint. This suggests that, within the old Buddhist literature from ancient India, pre-mythic stories about the Buddha’s life have survived. Further historical fragments can be retrieved from myth, for example the primary Pali account of the Buddha’s ‘awakening’, where we are told that Gotama considered not bothering with teaching, since nobody would understand him. After Gotama did decide to teach, the first person to encounter him, an ascetic called Upaka, was not impressed. Upaka asks who Gotama’s teacher is. When Gotama replies that he is fully awakened, and so has no teacher, Upaka simply shakes his head and walks off, saying ‘maybe’.

He emerges as a lone voice from the wilderness, inspiring others to join an austere cult of meditation

So a critical study of the textual record suggests a surprising story: Gotama doubted his own teaching ability, was not taken seriously by the first person to witness him (as the Buddha), and did not achieve notable success with his first audience. How, then, did he succeed? That the Buddha had a major effect on Indian culture and society cannot be doubted; no comparable attempt was made to preserve a record of any other figure in ancient Indian history. A good idea of Gotama’s personal impact can be seen in the testimony of an old spiritual seeker called Piṅgiya:

I see him in my mind, as if with my eyes,

diligently, day and night,

I spend the night honouring him,

and think there is no separation from him.

My faith, joy and mindfulness

do not deviate from Gotama’s dispensation,

Wherever the one abounding in wisdom goes,

I bow down in that direction.

What inspired such commitment? Although Piṅgiya’s declaration does not tell us very much, its position in the Sutta-nipāta (‘A Collection of Discourses’) – an old corpus of wisdom literature – is more revealing. Gotama here emerges as a lone voice from the wilderness, inspiring others with a call to join an austere cult of meditation. An important text in the collection is the Muni Sutta (‘Discourse on the Silent Sage’), almost certainly known to the Indian emperor Aśoka (who reigned c268-232 BCE) as the Muni-gāthā (‘Verses on the Silent Sage’), and so in its extant form dating to the 4th century BCE, not very long after Alexander the Great’s Indian campaign (c326 BCE). In this text, the Buddha describes the sage as a radical outsider:

Danger is born from intimacy, dust arises from the home. Without home, without acquaintance: just this is the vision of a sage.

Avoiding the enveloping ‘dust’ of society, the sage remains aloof from worldly values, ‘not trembling amid blame or praise, like a lion not shaking at sounds … like a lotus not smeared by water’. Focusing his attention instead on the quest to cultivate deep states of meditation in the forest, the sage is likened to a swiftly flying swan, whereas a householder is imagined as a blue-crested peacock, beautiful but slow. A comparable image is found in the Khagga-visāṇa Sutta (‘The Rhinoceros Discourse’), another old text of the Sutta-nipāta, which points out that even two gold bracelets will clash when worn on the same wrist. The message is clear: it is better to wander alone, in the wilderness, like the single-horned Indian rhino.

Gotama’s otherworldliness can also be seen in many stories about his quietism. The account of his visit to Prince Bodhi’s ‘Kokanada’ mansion says that he remains silent and ignores the invitation to ascend to the upper terrace. But after casting a telling glance at his assistant, Ānanda, the Prince is told to roll up the cloth covering the stairs: Gotama is so removed from civilised norms that he will not walk on covered ground, and will not even break his silence to explain himself. Elsewhere, Gotama accepts invitations by staying silent, and expresses his appreciation of being alone in the forest or on the road. He also advises his followers to maintain a ‘noble silence’, so that when Ajātasattu, king of Magadha, comes to visit, the intense quietude he encounters is so overwhelming that he worries about being lured into a trap.

Gotama’s quietism also finds enigmatic expression in his teaching. Most striking is what could be called the ‘dialectic of silence’: when asked abstract metaphysical questions, such as whether the world is eternal, whether the soul is different from the body, or what happens to a liberated person (tathāgata) after death and so on, Gotama stays silent, or points out that he has set these subjects aside. The reason for this was partly pragmatic: such questions are said to serve no spiritual purpose. But there is a subtler reason too.

In the early Pali texts, the Buddha’s philosophical reticence is sometimes explained as a form of skepticism: Gotama does not accept the presuppositions of the questions. The term buddha (‘awakened’) indicates that normal experience is a dream from which Gotama has awoken. One old refrain tells us that Buddhas draw back ‘the veil’ from reality. Gotama thus sees things as they actually are and, from this awakened perspective, realises that ideas such as ‘world’, ‘self’ or ‘soul’ are not ultimately real. And if these aspects of experience belong to the unawakened perspective, the questions are unanswerable. The ultimate truth to which Gotama has awakened is that our world of experience belongs in the mind:

I declare that the world, its arising, cessation and the way thereto occurs in this very fathom-long ‘cadaver’ (kaḷevare), endowed with perception and mind.

This peculiar teaching suggests that the world in which we live is a state of experience, not an objectively real entity. This explains Gotama’s focus on the painful nature of human experience, and especially the means of deconstructing it. This analysis is not without logical problems, however. For if individual existence in the world is a conceptual or cognitive construction, what is the point of the spiritual life? Without an essential subject or ‘soul’ to realise an essential reality, how can spiritual discipline be worthwhile and meaningful?

It is a wise allegory on the essential tragedy of the human condition, and the possibility of redemption

Early Buddhist teachings bypass these problems by focusing on the fact of suffering (or unsatisfactoriness: dukkha), and the possibility of its cessation (dukkha-nirodha). In this elegant scheme, spiritual practice is a form of mindful introspection: by paying close attention to experience, and keeping guard over the likes and dislikes that pull one into it, the painful experience of conditioned reality unravels by itself. This approach to the spiritual life is well-expressed in the Buddha’s teaching to a seeker called Mettagu:

Whatever you observe, Mettagu,

above, below, or all around in the middle,

Warding off delight and attachment to these objects,

let not your consciousness linger in being.

Living thus, mindful and diligent,

the wandering mendicant abandons appropriations;

That wise one, right here, will abandon suffering,

birth, decrepitude, sorrow and lamentation.

Early Buddhist accounts of the path to liberation build on this approach. The classic source is the Sāmañña-phala Sutta (‘Discourse on the Fruits of Asceticism’), which lacks anything that could be described as a meditative ‘practice’. It instead indicates that cultivating mindfulness leads to the abandoning of negative mental states, following which the mendicant must only sit in solitude, being mindful ‘around the front’ (of the body), for meditative transformation to occur. The penultimate stage of meditation, which paves the way for the ineffable state of liberation, is described as follows:

With the abandoning of pleasure, pain and all former states of joy and dissatisfaction, the mendicant abides in the fourth stage of meditation, a complete purification of equanimity and mindfulness. Just as a person might sit down, his entire body up to his head wrapped in white cloth, so too does the mendicant pervade his body with a purified mind, so that no part of his body is not pervaded by it.

Like the dialectic of silence, this account of personal transformation studiously avoids the metaphysics of ultimate reality. Suffering ceases. Neither a soul nor a spiritual reality is asserted. Gotama’s system is subtle and elusive – no wonder he hesitated before teaching, and no wonder that later followers created the Buddha myth. Perhaps the early myth-makers realised that Gotama’s movement needed more than meditative quietism, and a teacher who would not answer certain questions. Instead they attempted to capture some of Gotama’s truths in a poetic guise. The myth of the Buddha as a prince, sequestered in a palace and blind to the suffering of the world, is a wise allegory on the essential tragedy of the human condition, as well as the possibility of redemption through awakening.

We are lucky that the myth-makers did not tamper too much with received traditions. This allowed early stories about Gotama to survive, and even if the textual record is partial and fragmented, its depiction of Gotama as a wandering sage is carefully drawn and surprisingly fresh. As the Muni Sutta states, the sage remains aloof from society, like ‘the wind not caught in a net’. According to the Sāriputta Sutta, another old text from the Sutta-nipāta (and probably also mentioned by Aśoka), the wilderness is the proper setting for spiritual discipline, despite its many dangers. It is here that a mendicant can mindfully observe his inner desires, and so come to abide with a ‘released mind’.

Over the millennia, the fragmented Buddhist movement lost sight of Gotama’s lifestyle and ideas. Monastic institutions preserved mythic versions of his Dharma, and in most places these provided essential support for the state. When some of these institutions migrated to the West in the 20th century, they brought local traditions with them, rather than authentic teachings of the founder. The modern mindfulness movement is a good example. The Americans who adapted mindfulness in the late-20th century drew on a 19th-century revival of meditation in Burma. And so rather than transmitting an ancient practice, they instead promoted a new spiritual discipline, formulated when Burmese Theravada was suffering in the shadows of the British Empire.

A feature of the modern mindfulness movement, inherited from fairly recent Burmese innovations, is its appeal to the laity, and hence its essentially therapeutic, rather than salvific, aim. Nothing could be further removed from the Buddha’s radical ideal of sagehood. By insisting on ascetic discipline and a life of homeless wandering, Gotama presented mindfulness as a total life commitment. Practised in this way, attending to the constituents of experience can be transformative: Gotama claimed it is a way of undoing one’s mentally constructed world, along with all its unsatisfactoriness and suffering.

Whether or not Gotama is correct, his voice is worth hearing. His antirealistic analysis – in which the world depends on the activity of our minds and sense faculties – could be a useful aid to modern cognitive science, and might broaden the focus of the mindfulness movement beyond therapy. More generally, perhaps, Gotama’s radical approach to enquiry could be revived. With its mix of meditation and rigorous conceptual analysis, it could open up a new domain of speculation, in which the pursuit of wisdom is an austere vocation, a lifestyle commitment, rather than a matter of religious belief.

Wandering around the ruins of former Thai kingdoms, from Ayutthaya to Sukhothai, one comes across ancient icons of the Buddha. Some still stand tall and brilliant; others can be found here and there, under trees and enveloped in creepers, their colours gently fading, their older aesthetic crumbling into oblivion. A complete lineage of images, going all the way back to the Buddha, would take us past the exquisite icons of the modern age, and beyond the great remains of antiquity. The trail leads us deep into the forest, and it is here that we find Gotama, the Sakyamuni.

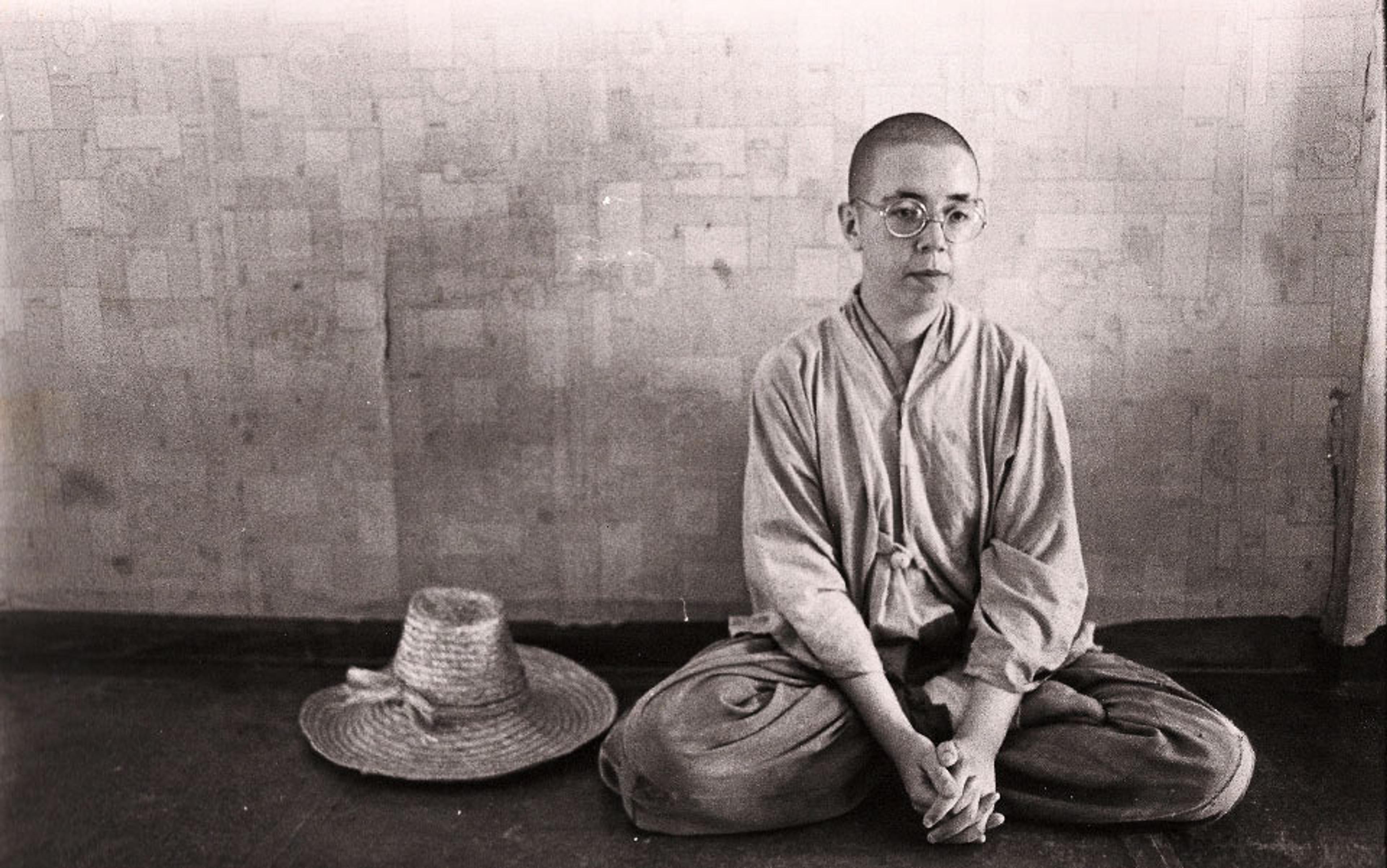

Sleeping out in the open, eating once a day, and frequently on the road, Gotama cuts a more austere figure than expected. His silent wisdom comes from somewhere else. We learn about his early failures, and then the strange story of his success: how he created an ancient cult of meditation, through enigmatic silence, radical ideas, and a simple insistence on being mindfully aware of the moment.