A suburban playground on a cold winter’s day. A man in his early 30s, wearing a beanie, leather jacket and scarf, pushes a toddler on a swing, a dead look in his eyes. On the climbing frame, twins are jostling each other. Their mother stands underneath, hopping from foot to foot, her eyes darting from one girl to the next, issuing warnings, instructions; her voice rises anxiously in pitch. Looking around, I see only one adult smiling, but then she’s talking to her friend; their children are some way off, fighting each other with sticks.

There’s nothing particularly striking here. It could be any day of the week, in any town. And there’s nothing revelatory about the thought of parents secretly wishing they were anywhere else but the local playground, perhaps envying their childless friends; even wondering, during the sleepless nights, or in the aftermath of a fight with a recalcitrant teenager, why they had children at all. What is distinctive of our times is how few parents — still, even in our post-Freudian age — will openly admit to feelings of ambivalence towards their children. In an age where very little — from sex to money — is left a mystery, parental ambivalence remains one of the last taboos.

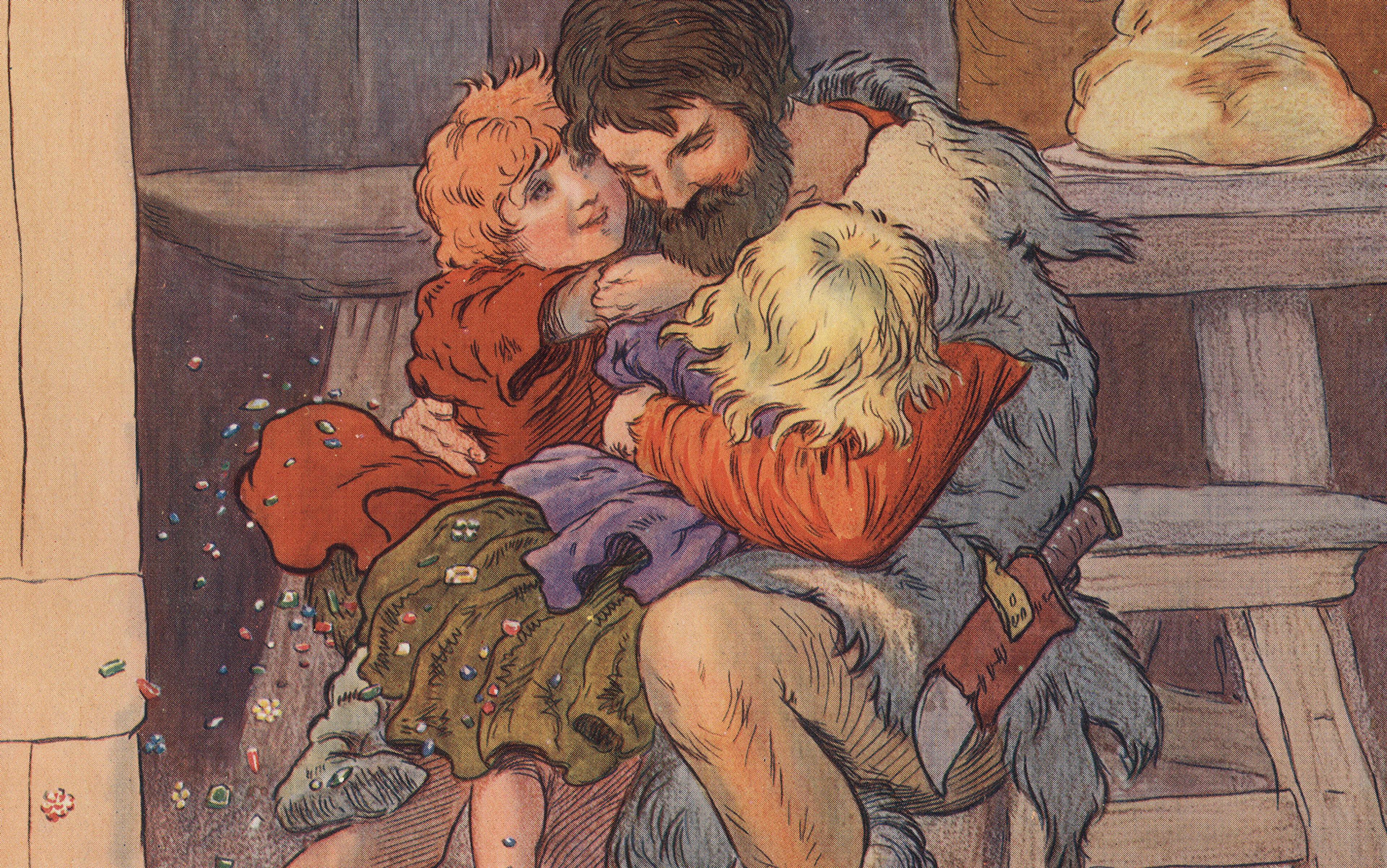

And yet the fact of parental ambivalence is a truth as old as mythology itself. Think how many fairytales begin with children being cast out by parents, either, as in the Brothers Grimm story ‘Brother and Sister’, being forced to leave on their own; or, like Hansel and Gretel, abandoned in a place from where they cannot find their way back. The fate reserved for older children, often adolescents, is usually more severe: the jealous queen in ‘Snow White’ orders her stepdaughter to be killed; and, in ‘The Three Languages’ by the Brothers Grimm, the king, frustrated by an adolescent son who persists in going against his wishes, eventually casts him out and orders his servants to do away with him. The narrative use of the wicked stepmother is worth noting here: it’s as if the child intuitively understands that his mother (and indeed father) can sometimes harbour hostile feelings towards him, but it’s safer to locate this cruelty in the figure of the stepmother, who can then be dispatched to a bloody end.

When hostility is denied an outlet in words, where else can it go but outwards, in the form of some kind of violence, or inwards as depression?

Nursery rhymes similarly reassure parents that there is nothing new about sometimes feeling murderous — rather than perennially loving — towards their children. And indeed what parent, their sleep broken yet again by a colicky baby, has not found some relief in being able to gently sing of the bough breaking and the cradle falling to the ground at the same time as they rock their baby back to sleep? Or secretly enjoyed the sadism meted out to the little darlings — the dismembered digits, the immolation, the starvation — in Heinrich Hoffmann’s 19th-century stories about children behaving badly in Der Struwwelpeter?

But first, some definitions. In modern usage, ambivalence is often taken to mean having mixed feelings about something or someone. This, though, is a watering down of the concept. As developed by psychoanalysis, ambivalence refers to the fact that, in a single impulse, we can feel love and hate for the same person. It’s a potent, unpalatable idea; and in the grip of intense ambivalence we can feel overwhelmed and confused, as if a vicious civil war is underway inside us: no wonder we’d rather render it toothless. And yet, as any honest parent will tell you, this is often how it feels. Speak of it, though — as Lionel Shriver did in We Need to Talk About Kevin (2003), where Eva, the novel’s narrator, openly admits to deeply ambivalent feelings about her son Kevin — and you will face criticism, even ostracism, from those who would rather not believe that parents can ever harbour such feelings. The problem with Eva, of course, was not that she had ambivalent feelings towards her son, but that she dissembled throughout Kevin’s upbringing, pretending, through all her frantic biscuit-making, that all she felt for her cold, unlikeable son was love.

The question is why she, like so many parents, found it so hard to acknowledge her ambivalence, even to herself. Part of the reason must be that we all know — even if we’re not abreast of current statistics — that we live in a society in which shockingly high levels of violence are inflicted on children. According to the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, one in four young adults is ‘severely maltreated’ during childhood, whether in the form of sexual, emotional, physical abuse or neglect. It’s a startlingly high figure, by anyone’s reckoning. And, if we acknowledge that we, too, sometimes have less than loving feelings towards our children; if we, too, sometimes have the wish to hurt, even if we are able to restrain ourselves, then does this mean that we too could be abusers? Every day, it seems, brings a new story of parental violence, neglect or abuse — a father killing his children and partner and burning down the family home; a couple being accused of murdering their toddler; or the ‘feckless’ mother who abandons her own daughter to take a holiday. Who would not want to put as much distance as they can between such cases and their own situation? Hence the attention given to a novel such as The Slap (2008) by Christos Tsiolkas, where the inciting incident, and cause of great parental angst, is a grown man slapping a badly behaved three-year-old boy (not his own son) across the face.

Societal pressure exacerbates the situation from the outset. ‘Congratulations!’ friends say, on learning news of pregnancy. And of course we might be pleased; but we might also be anxious, dimly aware of the pressure to be unequivocally and everlastingly grateful for our good fortune. The greatest pressure, of course, is placed on the mother, who is expected to have an uncomplicated and adoring relationship with her baby; who is expected never to tire of playing with Lego. For mothers, the state of motherhood itself is credited, in the words of the psychotherapist Rozsika Parker, author of Torn in Two: The Experience of Maternal Ambivalence (1995), with being able to ‘satisfy a woman’s longing for union’.

But what if, Parker writes, a mother doesn’t ‘experience a joyful sense of love and oneness’ immediately after giving birth? ‘Some do but many don’t,’ she says:

… and warnings that it may not happen tend to fall on deaf ears. For women carry babies for nine months within a culture which represents the postnatal mother-child social relationship as if it represented the intrauterine state of antenatal union. The 19th-century tradition of presenting a new mother with a pin cushion bearing pins arranged to spell out the words ‘Welcome Little Stranger’ was in many ways a more appropriate representation of the state of affairs.

Pins notwithstanding, consider how much harder to admit to ambivalence when you’ve been through five cycles of IVF; or have spent several years being grilled by your local adoption agency before being allowed to become a parent. Whatever its constitutional components, the current high incidence of post-natal depression in the UK, where some three out of ten new mothers are said to be afflicted, cannot be unrelated to the pressure placed on mothers to deny their ambivalence. Once hostility is denied an outlet in words, where can it go but outwards — in the form of some kind of violence — or inwards, as depression?

The paediatrician and psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott, who spent a lifetime working with children and families, understood why the scales of ambivalence might tip more towards hate than love. The baby, he wrote, ‘is a danger to her body in pregnancy and at birth’, he ‘is an interference with her private life’ and he ‘is ruthless, treats her as scum, an unpaid servant, a slave’. He ‘shows disillusionment about her’, he ‘refuses her good food… but eats well with his aunt’; then, having ‘got what he wants he throws her away like orange peel’. He ‘tries to hurt her’, and, ‘after an awful morning with him she goes out, and he smiles at a stranger, who says: “Isn’t he sweet?”’

And then there is the effect of the arrival of a third party — however planned and wished for — on a couple’s relationship. Nora Ephron, who wrote When Harry Met Sally… (1989), saw it explosively: the birth of a baby, she once said, was like ‘throwing a hand grenade into a marriage’. Lionel Shriver’s mother felt similarly, warning the author, then in her mid-30s and newly in love, that, should she and her partner decide to have a child, motherhood would ‘completely transform’ their relationship. ‘Though she did not spell it out,’ Shriver has written, ‘there was no question that she meant for the worse’. And yet many couples, finding themselves drifting apart, or fighting, opt to have a baby (or another baby) in the belief that this joint creation will restore their lost unity.

Fortunately, societal expectations are changing, albeit slowly. The feminist movement of the 1960s — typified by such books as Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique (1963) — overturned long-held received wisdoms that designated motherhood (in the words of the social researcher Mary Georgina Boulton) as ‘intrinsically rewarding and not problematic’ and refocused attention on women’s actual experience of motherhood. Even so, Friedan set the blame for maternal ambivalence at society’s door, rather than acknowledging that, like paternal ambivalence, the very essence of the maternal role is contradictory, and the feelings roused in parents are equally powerful and often confusing.

Even now, when 21st-century mothers admit to ambivalence, as Rachel Cusk bravely did in her memoir A Life’s Work (2001), they are attacked as irresponsible, even unfit to be parents. And so we continue to enter parenthood blindly, relieved and proud that our genes will survive, and oblivious to the unrelenting demands ahead, or that we have unwittingly signed up for a job for life, with no training, pay, prospect of sabbatical leave, change of career or get-out clause. It’s a job that will require endless investment and patience and, if all doesn’t go too badly, one in which we are finally made redundant. Of course there are rewards, but these come fitfully and often when we least expect them.

Estela Welldon, author of the acclaimed and influential study Mother, Madonna, Whore: The Idealisation and Denigration of Motherhood (1988), says that the trend to have children later in life — and the consequent feeling that having them involves considerable sacrifice — can trigger hostility towards children. ‘For people these days, having children is a big investment,’ she told me. ‘They often give up part of their careers. Parents do so much for their children that sometimes I wonder if the parents need the children more than the other way around. The parents are investing a lot, and they expect a lot in return.’ If the return is not forthcoming, hostility may not be far away.

Before having children, and provided we’ve moved on a little from the maelstrom of adolescence, it is possible to think of ourselves as good people: patient, kind, loving, tolerant

Hostility can also be triggered when we are made to face things we’d rather not. And few roles in life do this with as much relentless consistency as parenting. Before having children, and provided we’ve moved on a little from the maelstrom of adolescence, it is possible to think of ourselves as good people: patient, kind, loving, tolerant. A few years of parenthood strips us of these illusions and we see ourselves in the raw: capable of fury, rage, pettiness, jealousy — you name it. For children confront us with the infantile aspects of our own personalities, the parts of ourselves we’d most like to deny, and we can hate them for it. Worse still, they can thwart our wish, even our need, to feel loving and effective. When Mrs Morel, in DH Lawrence’s Sons and Lovers, acknowledges that she had not wanted her son Paul because of her relationship with her husband, she looks at her child with fear: ‘Did it know all about her? When it lay under her heart, had it been listening then? Was there a reproach in the look? She felt the marrow melt in her bones, with fear and pain.’ Aware of her ambivalence, she resolves to love him as passionately as she can. But with other parents, it can swing the other way: full of self-reproach for feeling ambivalent, we can hate ourselves — and then turn against our children for ‘making’ us feel this way.

The problem is not that we feel ambivalent towards our children, but that we try to deny it. If we do this, then before long we cease to know what is appropriate anger towards our children, and what is dangerous hostility. Through anxiety and uncertainty, we try to repress all our negativity — not only in ourselves, but also in our children. As Welldon cautions: ‘The important thing is that children of whatever age feel they have the right to express feelings of hostility and anger. The more they try to repress it, the more it will explode into action.’ So: deny ambivalence, in ourselves or in our children, and you will find yourself living at the volcano’s edge, anxiously anticipating an eruption, whether physical or verbal.

What, then, can psychoanalysis teach us? And how might therapy help? Let me describe a hypothetical patient, based on my clinical experience. Sadie’s mother died giving birth to her, and she was raised by her father. In an attempt to make her depressed and lonely father happy, Sadie became a perfect student. Whatever negativity she felt, she repressed. By the time she was a young adult, she no longer knew what she felt. When her boyfriend left her with two young children, rather than express her rage outwardly, she made an attempt on her life. In treatment, she found it hard, especially in the early days, to express any kind of hostile feeling towards me. Whenever I drew attention to her need to keep the relationship with me calm and free of conflict, she would agree, smile, and change the subject.

Motherhood provoked great anxiety, and Sadie found it very difficult to tolerate any kind of negativity from her children, aged six and four. In therapy, though she denied her own negativity towards me, her actions revealed other feelings: after holiday breaks, she would routinely ‘forget’ to come to her session, causing me to worry about her. Only gradually, by acknowledging the pain of her own losses and the degree to which she repressed her anger, did she begin to be more overt in her hostility towards me. In turn, as she discovered to her astonishment that I could survive her antagonism, she became more assertive with her children, and they began to calm down at home and at school. Family life is still very hard for her, but she is starting to feel less anxious whenever she feels negative feelings rise up in her; less afraid that, by voicing even the smallest degree of negativity, she will destroy everything.

Not all therapists would agree that negativity must be voiced in order to liberate the patient. There are those who champion the concept of the ‘corrective emotional experience’, first propounded in the 1940s by the psychoanalyst Franz Alexander, which would, he said, ‘repair’ the effect of previous traumas. But Estela Welldon, along with most psychoanalytic practitioners, does not favour this approach. ‘We are not therapists so that people can love us. People need to be able to not like us. People slam doors at me, they shout at me. I facilitate their expression of their anger.’

Her point is well made, since once words have been found for anger, then the emotion is no longer literally embodied. In ordinary terms, once we have said how angry we are, we are less likely to hit or shout or do harm. Then, like Sadie, we are more likely to be able to draw appropriate boundaries; to be able to say ‘no’ to our children; and to defend our own interests in a way that is neither selfish nor aggressive.

In one of his papers, Donald Winnicott related a story that has relevance to all parents struggling with ambivalence. During the Second World War, he and his wife found themselves looking after a nine-year-old boy with a history of violence and truancy. ‘My wife very generously took him in and kept him for three months, three months of hell. He was the most lovable and most maddening of children, often stark staring mad.’ When the boy became violent, Winnicott said, he ‘engendered hate in me’. The fact that Winnicott allowed himself to acknowledge this meant that he was able to contain his own impulses to retaliate. ‘Did I hit him? The answer is no, I never hit. But I should have had to have done so if I had not known all about my hate and if I had not let him know about it too.’

The sanction that Winnicott devised for the boy might seem somewhat Victorian, but it enabled him to contain his own impulse to hit the boy:

At crises I would take him by bodily strength, and without anger or blame, and put him outside the front door, whatever the weather or the time of day or night. There was a special bell he could ring, and he knew that if he rang it he would be readmitted and no word said about the past. He used this bell as soon as he had recovered from his maniacal attack… The important thing is that each time, just as I put him outside the door, I told him something; I said that what had happened had made me hate him. This was easy because it was so true.

Interestingly, Winnicott never had his own children, which might have facilitated his uninhibited investigation of ambivalence, since there were no offspring whom he might have felt the need to ‘protect’ from reading his thoughts.

Controversially perhaps, because it implies that patients are not all that different from children, Winnicott claims that the analyst, just like the mother, must be able to hate as well as love his patients: ‘However much he loves his patients he cannot avoid hating them and fearing them, and the better he knows this the less will hate and fear be the motives determining what he does to his patients.’

If we deny our hate, and try to suppress our ambivalence, then we become risky to others. In this state of denial, intent on seeing only one side of our natures, we are apt to demonise others, to cheer tabloids when they ‘name and shame’ paedophiles; to wallow in the stories of Jimmy Savile’s abuses at the same time as we turn a blind eye to the moments when we lash out at our own children, or allow our own cruelty, rather than appropriate discipline, to inform our sanctions or punishments.

Becoming aware of our destructive impulses is painful, and it can bring on a degree of guilt-driven depression. But guilt sometimes has its uses. It can spur thought about how to do better next time; to repair what we might have damaged. And in the end, our children survive our hate, just as they survive our love.