Recently I watched again the classic film adaptation of The Bridges of Madison County and felt a bolt of recognition at what is known in film circles as the ‘Madison County Moment’. Francesca (played by Meryl Streep) is with her husband in their Chevy, and her lover is in the pick-up truck in front. She grips the door handle, her life on a pivot: should she stay or go? Caught between duty and freedom, she’s in no doubt of the love she feels for Robert (Clint Eastwood), but to pursue it would entail destroying her family and living with a haunting regret. However, if she stays, will this passion persist in her consciousness as an unrealised, unlived life? When young and childfree, it is much easier to break away from a partnership and start afresh, but those of us with family need to understand that damage is inevitable, that it’s simply not possible to shake off the past. ‘No matter how much distance we put between ourselves and this house, I bring it with me,’ Francesca had told Robert on the last evening they’d spent together, when he’d begged her to leave with him. ‘And I’ll feel it every minute we’re together.’ The life that was left behind.

Married to a good man, with two young children, I too, was struck by true love for someone else. We met at a dinner where I broke my molar on an olive stone. I caught myself opening my mouth to show him the severed tooth. Parts of my body were crumbling, I was ageing, time was running out. My diary entries from the time were breathless with wonder. Whenever he was in the same room, I simply wanted to be near him. After many years of ambivalence in my marriage, the clarity of my certainty came as a relief, a profound comfort, restorative in its ease. It helped steady the ground as the life I knew threatened to shatter. I did not want to destroy my family, but I’d opened the door on what had felt like a cage, and a broken bird had finally found its wings. It was not possible to shut the door again, and I did not want to live the rest of my life wondering what might have been. I was well aware of my privilege compared with women in Francesca’s time, when leaving a marriage entailed losing everything. I was able to take the children with me.

But this was not the easy road: leaving a ‘good enough’ marriage in the hopes of creating something better often fails. The foundations of a stepfamily are riven by the fault lines of failure and loss, divorce or death, with children having no say in the matter of rebuilding – who did not choose this new family structure. Constructing a new life from the fragments left behind can feel like trying to glue back a ceramic vessel that has smashed into a thousand tiny pieces and restore it to its original form: the contours of the break will always be visible. How you knit the jagged edges of two broken families and make it work brings other challenges besides, particularly in the West, where we look to the nuclear family and its image of wholeness and safety as our guide. How this image beats like a heart in the imagination – the ideal of a natural union, mother, father and biological children. If my second attempt to create a family has a fighting chance of defining itself, it must be set free.

Through the rosy tint of a new romance, anything feels possible; but add ready-made children from a previous marriage and the picture distorts. In the early months, I turned to R and said: ‘You’re not only taking me on, but my children as well.’ Seven and nine at the time, their presence was intense and vital. He nodded reassuringly, but I could see the panic in his eyes. When the four of us were together, they attached themselves to me like Velcro, clinging to my hands and waist, creating a six-legged creature; they were disruptive over dinner, vying for my attention. I longed for uninterrupted time to nurture this nascent relationship without those grasping hands, but I also felt wretched: I was their mother, and they were children. This man was a comparative stranger. They were still coming to terms with his explosion into our lives, the result of a decision I’d made for myself. The weight of my choice and my power to change the course of their lives was paralysing. I wondered if this selfish act would be a curse, always getting in the way of cohesion and happiness?

Each time I walked into my ex-husband’s rental home, the smell of his clothes took me back to our merged lives, the former cradle of us and our family whole. Also, the oddness of familiar details: pots and pans given as wedding presents; mugs we’d both drunk from; chairs we had bought one sunny day when the two of us were hopeful for our future. Later, visiting his new family home, where he lived with his second wife and toddler, a polished stone elephant, cold to the touch, transported me straight back to our old family home, with windows open to birdsong and our children at ease in their neighbourhood: bonds we had worked hard to nurture. Echoes of the past like ringing bells of memory. Bittersweet.

I invited R into the centre of our new home and made our relationship the children’s central point of navigation

I was now in the world of split assets, reduced income, a deep sorrowful pain overwhelming me each time the four of us were in a room together. The pendulum of intense mothering, followed by the drag of absence when the children were gone, our lives unmoored and unstable, all of us caught up in grief. Left alone at weekends, I felt uptight and distracted, an aching in my bones. Restlessly I kept looking over my shoulder for something lost, an essential part of myself like a foot or a hand accidentally forgotten. During this transitionary period my heart was still marked by the first-time family; it was important to honour it for the sake of all that was to follow.

I can’t say that R and I got it right, but we took things very slowly, and I followed my instincts which, in the initial years, were almost entirely aligned with my children. When R and I finally moved into a house together, I suggested the kids have their bedrooms on the same floor as ours, and that R take the two attic rooms for his study. A secret part of me that wanted to tuck him away, for his sake as well as ours; I wanted to be available to my kids, but I also dreaded them disturbing his work. We considered getting insulation between the floors.

As the moving-in date got closer, I realised it may be better for the children if I invited R into the centre of our new home and made our relationship the children’s central point of navigation. He would have his office on the same floor as our bedroom, and the children – almost teenagers now – would have the privacy of the attic. Still, I spent those early years in a state of hyperalertness, intervening whenever R showed signs of assuming a parental role; I would echo his commands as if softening them with the cotton wool of my approval. Whenever I disagreed with him, I rushed in to defend the children, and this made him retreat into near-silence.

Most stepfamily literature focuses on stepparents because they are the outliers. But it is the job of the biological parent to hold all the disparate pieces together: keeping the children happy, honouring the wishes of the ex-partner, while trying to keep the new relationship alive. I was anxious if R was left in a room with the children without me as intermediary. But this attempt to placate and to harmonise, to resist discomfort, delayed what was inevitable – that R needed a voice in his own home, and a relationship with my children. Not so much a father as a father-figure; a constant in their lives, and a positive role model of a very particular kind. We did not set out to form a stepfamily – we simply fell in love – and we moved slowly so as not to force things. In fact, it was my children who first used the term ‘stepfamily’.

Over the past century, families have become more fluid to include non-married parents, same-sex parents, polyamorous coupling and scatterings of half-siblings, yet the nuclear family ideal still dominates. In the United States, the term ‘blended family’ with its positive connotations has slowly been taking over the term ‘stepfamily’, keeping pace with shifting demographics. According to Patricia Papernow’s paper for therapists ‘Clinical Guidelines for Working with Stepfamilies’ (2017), in the US 30 per cent of children will spend some time living in a stepfamily before they reach adulthood; 26 per cent of all marriages include stepchildren, and about 42 per cent of all Americans have a close stepfamily relationship, which includes stepparents, children, parents and grandparents.

These figures are significantly higher than in the United Kingdom, where the 2021 census suggests that stepfamilies make up just under 5 per cent of all families (defined as married, civil-partnered or cohabiting, with or without children, or a lone parent with at least one child). The term ‘blended family’ has not yet overtaken the more predominant term, stepfamily, in that, according to the census, it involves at least one child of the stepfamily being the biological child of both parents, alongside stepchildren from previous partnerships.

The etymology ‘steop’ in Old English, via German, means ‘orphan’, reflecting that, historically, most marriages ended because one parent – often the mother, often in childbirth – died; and stepmothers particularly have taken a bad rap, as evil or avenging monsters in fairy tales like Snow White and Cinderella. Even so, ‘stepfamily’ feels more synonymous with the reality of starting and maintaining a second family than ‘blended’.

To me, ‘blended’ suggests a homogenised state of merging; or, more precisely, of erasing differences and becoming indivisible; the new family, a seamlessly repaired vessel trying to replicate the original before it was ruptured. This attempt at merging into one is where so many stepfamilies go wrong. How families deal with this tension differs dramatically according to what age the children are when the adults meet, and how active a role the stepparent takes in everyday parenting. The term ‘blended’ risks denying this tension. The stepparent is a parent and not yet a parent, the stepfamily is a family but not a family, and one of the base-level challenges to the stepfamily is that its bonds, at least initially, give primacy to pre-existing biological connections rather than the romance that birthed it. Blending is a process that can happen over decades, and sometimes not at all.

The nuclear family cut women off from their extended families and the greater community

Papernow is a leading expert on stepfamilies and the author of one of just a handful of clinical books on the subject, Surviving and Thriving in Stepfamily Relationships (2013). She claims that, in stepfamilies ‘straining’ to recreate the atmosphere of the first-time family, grief is always present. Papernow has long advocated for more study of stepfamilies and more focused training in stepfamily therapy. Not least because, at its most extreme, the ‘straining’ can result in what she calls a ‘scrap and build’ culture, whereby the biological mother or father is exiled entirely, with the stepparent stepping into the breach. The surname changes that result can deny a child’s previous identity and erode their connection with the wider family of grandparents, cousins, uncles and aunts.

Historically, popular representations of stepfamilies haven’t helped: the US sitcom The Brady Bunch (1969-74), with its symmetry of three girls and three boys, a massive house in the Los Angeles suburbs, and the original separation due to bereavement on Mike Brady’s side. There’s no mention of what happened to Carol Brady’s husband. She even denies her stepson’s identity by claiming that the only ‘steps’ in their household lead to the second floor. This image reeks of shame and whitewashing, a rubbing-out of the lives that came before, and a desperate attempt to make two halves a whole. It is a false dream.

Besides, the conventional family structure does not work for everyone. Back in the day, my ex-husband and I formed a nuclear family, by design. He worked long hours running his own business and I cared for the children, trying and failing to keep my career going after my debut novel was published the same year I gave birth to my first child. I was incredibly lonely, and isolated, living in a different city from my wider family; plus, I’d bought into ‘attachment parenting’ and was frightened of sending my children to nursery or asking for external help from strangers before they were ready. In Matrescence (2023), the writer and journalist Lucy Jones describes feeling similarly isolated ‘in a white Western culture without formal rituals and traditions without a culture of asking for and accepting help.’ Formed in response to industrialisation, the ‘nuclear family’ took root when families migrated to cities and the home became a private and nurturing space, locking women into motherly roles to raise healthy men who could go out to work, and healthy women to become their wives. The nuclear family cut women off from their extended families and the greater community. Privacy, at its best, is the family’s strength, but privacy can also signal its downfall, setting the family apart: elevated, rule-bound, protected but enclosed. The carapace can foster confidence, resilience, safety – but also dysfunction, violence and abuse.

I was flailing in the nuclear family, grasping at alternative ways of living in order to bridge the gap growing between my husband and me. After dinner, I’d corner him and tentatively suggest he take a three-month sabbatical; we could rent our house, hire a camper van, give the kids an adventure, give ourselves the chance to live more profoundly as a family, with equal responsibilities. But this wasn’t to be. Our mortgage was too big a burden; the risk of being out of work too great. There was no wriggle room, no flexibility. I felt trapped by convention in a life in which I didn’t belong. I had been drawn to marriage for its immovable vows, the idea that it might create a frame for me to hold on to and force me to grow up. But, also, because it was what everyone else was doing. These were not solid reasons. Raised by a single mother, with a father who’d left us to pursue an alternative lifestyle in a commune, a four-cornered family was not the most natural configuration for me. Unhappy inside the construct I had chosen, I began to see other possibilities.

In Matrescence, Jones references recent research in neurobiology that supports alloparenting, that is, providing parental care to a child unrelated to you. The experience of pregnancy is not essential for reconfiguring a woman’s brain into infant-caring mode, while hands-on parenting can rewire a male brain in similar ways to how a female brain is moulded through pregnancy and childbirth. Such evidence supports those individuals wanting to build networks of support for their children beyond the nuclear structure, but also those struggling to claim their space as a stepparent. According to Papernow’s research, stepchildren tend to do better within cultures that are more community centred, such as African American, Latino and Asian cultures, where childcare does not start and end at the family’s door, and children are accustomed to being nurtured or disciplined by grandparents, neighbours and family friends. This extended support introduces different influences, lifestyles and ways of being to the children, enriching their life experience, while taking the weight off mothers. Within African American families, it’s striking that ex-spouses are considered part of ‘a rich cross-household network of emotional, financial, instrumental, and spiritual support’; generally, there are friendlier relationships between mothers and the non-resident fathers, and non-resident fathers are more involved with their children than their white counterparts.

When my husband and I talked about separating, I told him we could sell the house and buy two smaller houses next door to each other. We could continue to coparent, but live apart. I have since discovered a term for such an arrangement – ‘a parenting marriage’. Coined in 2007 by the therapist Susan Pease Gadoua as a viable alternative to divorce and a form of practical parenting, it describes a situation where the emotional bonds are dissolved but the parental ties remain. At the time I suggested it, this seemed impossible: too painful, perhaps, but also too far from the norm.

What if the cracks are the very thing that give a stepfamily its power?

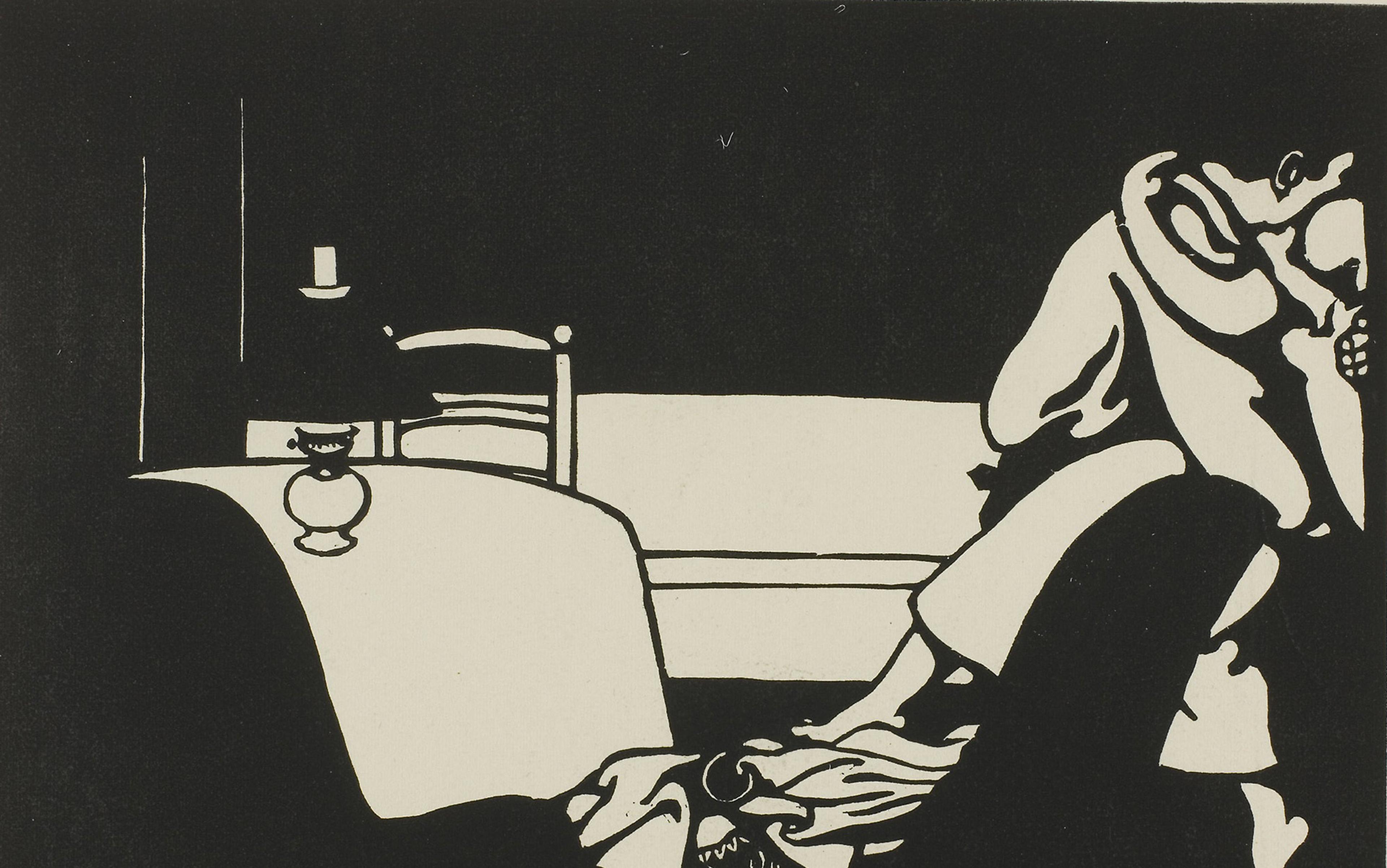

Mothers in almost every culture are programmed to bury their needs in the greater needs of family. Acting on their own desires, following their hearts, searching out their own private happiness – all of this is still perceived as transgressive and profoundly selfish. The writer Rachel Cusk is living proof of the attacks that women face when openly admitting their ambivalence, but she also nails how ‘othered’ women become when they go against the grain of keeping a family together, no matter what. In her memoir Aftermath (2012), which chronicles the wildly unstable weeks following the end of her marriage (she left), Cusk captures the exclusivity of family – but now from the outside looking in. She and her children are at a Christmas carol service, and she views the other families as if:

I were looking in at them through a brightly lit window from the darkness outside; see the story in which they play their roles, their parts, with the whole world as a backdrop. We’re not part of that story any more, my children and I. We belong more to the world, in all its risky disorder, its fragmentation, its freedom.

Cusk calls out how a two-parent family puts a wall between itself and the world, and how leaving a marriage hurls you into a rude reencounter with chaos. In the tentative stage of making a new life in Bristol with my children, I met a woman – another mother – at a party and told her the reason we had moved from London. ‘I went through a divorce,’ I said bluntly, and she flushed red and our conversation stalled, as if I was no longer a collaborator – as mother, as wife. I was hurt and felt ostracised, but I see now that I was a threat to other families struggling to maintain the nuclear norm; I had broken ranks, trashed the sacred contract, and made it possible they could too. The author Leslie Jamison writes beautifully in her memoir Splinters (2024) about the aftermath of walking out on a marriage with a young child. She captures her ambivalence:

When I was a kid, I liked to write fairy tales with unhappy endings. The dragon roasted everyone. Or else the princess left her prince standing at the altar and flew away in a hot-air balloon over the sea. Maybe this was a happy ending, just a different kind. Not a wedding, but an untethering. Sandbags hurled over the edge of the basket. Flames blooming under the silk.

More radically, I’ve begun to ask: what if the cracks are the very thing that give a stepfamily its power, if it’s the patchwork of love, individuality and experience that make it special? I like the term patchwork family – as opposed to step- or blended. It makes me think of the loving way we stitch together different lives, different interests, different needs, and the careful attempt at creating an imperfect whole. Much like a beloved building that has been altered and extended over the years, making a point of the demarcation between old and new, the patchwork family can be a proudly mongrel creation, rather than a seamless pastiche. A celebration of its past, together with the rich addition of its new present. The beauty is in the fault lines.

The Japanese art of kintsugi is an apt metaphor here. It is the art of piecing back together something precious with glue, but not with the intention of making the breaks invisible and replicating what was – instead, tracing the mended edges with gold makes a feature of them as they are integrated back into the whole. The seams are visible as a kind of golden scar that recalls the breakage, challenging our concept of beauty as something aligned with perfection. Borrowing from the Japanese philosophy of wabi-sabi, the imperfection is a new kind of perfection.

Perhaps the ghosts of the original family can be embedded in this new and beautiful creation. They are the splinters but also the gold leaf in the glue. They are strong enough to hold the possibilities of the first-time family that were cut short, and the way that life continues to shine bright in the expressions of the children who bear the genetic imprint of the absent parent; they are the connective tissue between two different worlds. This can be celebrated, not feared. Soon after we met, I took R’s hand and quoted part of the poem ‘The Summer Day’ (1990) by Mary Oliver: ‘Tell me, what is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?’ We took a risk. And we are still arranging the broken pieces and waiting for the glue to dry; but the gold is precious and bright.

Five years into our patchwork family, it is still a work in progress, but the children have an extended network – a stepmother, two stepsisters and R, adding to their lives and experience. Not long ago we got a puppy to join our old cat, a mongrel to fit our crossbreed family who instantly became a shared focus that gave everyone something to laugh (or scream) over. When we built a kitchen extension, each of us wrote our names into the wet concrete, forever marking ourselves, together, into the foundations of our home. These days I can be upstairs, knowing that R and the children are downstairs and that I don’t need to intervene; they have formed their own relationships, despite me, and have enough to talk about, whether it be the dog, or the washing up, or whether it’s time for my son to take out the recycling. House rules – the details of living – and our crazy pets have become the bonding glue in the absence of blood.

I know it was right to take the path untrodden, even if I regret the pain it caused. I can mourn what was lost and what might have been, but not the action that took me to that fork in the road. Wanting more for myself and not wanting to compromise by giving in to a life that did not feel right feels like the right path for me now, but also the right example to my children. Was it worth the sacrifice? When breaking up a marriage, Cusk tells us, you break more than just your personal narrative: ‘You break a whole form of life that is profound and extensive in its genesis; you break the interface between self and society, self and history, self and fate as determined by these larger forces.’ Knowing that I made the right decision for myself, and arguably by extension for my children, I have a deep sense of the responsibility of my actions, like a psychic wound that might never fully heal.

Jamison writes about hiraeth: a Welsh word that means the yearning for a home that no longer exists, or maybe never existed at all. But to her it feels more like a grieving of her marriage, missing not what it had been but what it hadn’t been, ‘what we’d both hoped it would be.’ There is such a primal need to join as one, like two different substances, poured into a vessel, blending to form an amalgam. When R and I first met, I sent him a Van Morrison song, ‘Tír Na Nóg’ (1986), and we often sang it together in the car, as a token of our joint nostalgia at the decades we missed not knowing each other: ‘We were standing in the garden wet with rain/And our souls were young again.’ Through that song we were able to imagine we’d met in a different incarnation, before this life, before these children. We could return to the land of the young, and never grow old, preserving our love.

But I no longer feel this longing for another life. I think back on Cusk writing about being relegated to the outside, looking in through a brightly lit window, and realise that this isn’t a disadvantage. We are alive in the now, in our new family. Our new reality, with a gash and then a scar – a golden scar – at its centre, is hard won. We are happy in the home we have built. As Cusk wrote in Aftermath: ‘We belong more to the world, in all its risky disorder, its fragmentation, its freedom.’ Our beautifully mended pot with its gold and celebration of difference is also highly functional, watertight and of great use to all.