Alan Bennett describes the experience perfectly: you’re halfway through a book by a long-dead stranger, and there it is: an idea or feeling ‘you had thought special and particular to you… set down by someone else … as if a hand has come out and taken yours’. I remember the first time this happened to me. Growing up as a bookish boy in a house with few books, I had learnt to be indiscriminate: the back of the proverbial cereal box, my father’s Soviet manual of civil engineering, or – as on this occasion – whatever my sister had brought home from the school library.

First Term at Malory Towers (1946) opens with an image of its heroine, 12-year-old Darrell Rivers in front of a mirror, pleased at the look of her new school uniform. ‘It’s jolly nice,’ she says to herself, ‘I like it.’ What will her first term at boarding school be like, she wonders. Like something in a school story? Probably not: ‘I expect it won’t be quite the same at Malory Towers.’ Straightaway, Darrell and her creator – the prolific and much-maligned children’s novelist Enid Blyton – own, and promptly disown, their literary inheritance: the British boarding-school novel. Like thousands of other Indian (or Australian or South African or Singaporean) children, I learnt from her books that there was such a place as Britain, that some children there went to boarding schools, and that other people wrote books about them.

The tradition of the boarding-school novel begins, more or less, with Tom Brown’s School Days (1857), that classic of hearty didacticism set in Rugby School when that most eminent of Victorians Thomas Arnold was headmaster. Its author, Thomas Hughes, made no apologies for all the moralism: ‘Why, my whole object in writing at all was to get the chance of preaching!’ he said to an imagined critic. Tom Brown has most of the tropes that would come to distinguish the genre he invented: the pre-prepubescent naïf leaving home for the first time; the bully; the climactic cricket match; the intense friendship and the equally intense rivalry; and, in all this, the fate of our young hero’s soul hanging in the balance. Will he choose the way of virtue or vice? Or will he become that awful thing, a prig, a contemptible parody of the good man?

Blyton was a late entrant to the game. By the time she tried her hand at the form in the 1930s, it seemed to have exhausted its possibilities. Far better writers than she had attempted it: Rudyard Kipling with Stalky & Co (1899) and P G Wodehouse with The Pothunters (1902). Not even the transplant to an all-female setting was original to her: Angela Brazil had got there first with The Fortunes of Philippa (1906), and the formula was perfected in the ‘Chalet School’ novels (1925-70) of Elinor Brent-Dyer. Blyton, like her heroine Darrell, knew the conventions well: each book had to be structured around a single school term, that intrinsically dramatic thing; the new girl finding her way around a strange new community in a fairytale landscape; the tragedies of unrequited childhood friendship; the brief reappearance of the largely invisible parents at half-term; the end-of-term exam and, vastly more important, the end-of-term lacrosse game.

Our first glimpse of 12-year-old Darrell staring into her uniformed reflection sets the tone for the series. Darrell sees only a schoolgirl staring back at her in the mirror; she wants to be nothing else. But we know soon enough that there is more at stake here. Darrell arrives at the railway station to catch the school train half-aware of her violent temper, almost a tragic flaw in Blyton’s hands. At the station, she meets, and falls for, Alicia Johns: clever, funny but, alas, callous. She doesn’t know quite what to make of Sally Hope, quiet and seething with mysterious resentment. But everyone knows immediately that Gwendoline Mary Lacey is a bad egg when they see her ‘clinging to her mother and wailing’. She is everything that in Blyton’s books signals depravity: blonde, fond of letting her hair loose, and waited on by a fussy mother who wears too many scarves. The girls watch her platform histrionics with scorn. ‘Alicia snorted. “See what’s made Gwendoline such an idiot?” she said. “Her mother! Well, I’m glad mine is sensible. Yours looked jolly nice too – cheerful and jolly.”’

‘Sensible’ is high praise at Malory Towers. The new girls are taught a new language, and with that, briskly initiated into a new form of life:

No one seemed to like two girls called Doris and Fanny. ‘Too spiteful for words,’ said Alicia … ‘They’re frightfully pi.’

‘What do you mean – pi?’ said Gwendoline …

‘Golly – what an ignoramus you are!’ said Alicia. ‘Pi means pious. Religious in the wrong way. … Trying to stop people’s pleasure. …’

Blyton, like Hughes, was a brazen preacher. ‘My public,’ she wrote, ‘bless them, feel in my books … a sure knowledge that right is right, and that such things as courage and kindness deserve to be emulated. Naturally the morals or ethics are intrinsic to the story.’

Will Darrell be a success? Will Sally, or Alicia, or Gwendoline? It is all splendidly uncertain at the start. Recall Alfred Hitchcock’s neat definition of suspense: you show the audience a bomb that’s about to go off in five minutes, and then you have the characters talk baseball. Blyton’s bomb is the half-formed character of the 12-year-old girl with its infinite capacity for anger, jealousy, cruelty, pettiness and self-deception; she lets us know where her characters are weakest, hints at catastrophe, then she has them all play lacrosse. I, for one, was hooked.

Shortly after she arrives at Malory Towers, nervous Darrell is taken to the headmistress, Miss Grayling, to hear the words she says every year to the new girls: ‘I count as our successes those who learn to be good-hearted and kind, sensible and trustable, good, sound women the world can lean on. … [E]asy or hard, [these things] must be learned: if you are to be happy after you leave here, and if you are to bring happiness to others.’ There is no mention here, or indeed anywhere else, of husbands or children. Miss Grayling promises or, what is more honest, offers the hope of, happiness. And the surest way to be happy, she suggests, is to take the happiness of other people just as seriously as your own.

The books’ drama is structured around this idea. The characters must face up to their own faults and their failures of empathy, confront the consequences of their own actions when they cause grief to themselves and others. What goes around at Malory Towers, more reliably than in real life, comes around. But this doesn’t always take the form of punishment in the conventional sense. The punishment for being a certain kind of person – self-involved, petty and malicious – is to have to live as that sort of person.

The girls at Malory Towers are archetypes. Yet, little about the books’ plotting is obvious or inevitable. Blyton’s characters deliberate, make choices, act, are capable of remorse and (within limits set by their temperaments) of growth. They are, in the sense that really matters, free. What stands in the way of goodness is, for them as for all people, the temptation to solipsism.

The wages of sin at Malory Towers is solitude. The girls’ most effective rebuke to egotism gone wild is, in a wonderfully medieval-sounding phrase, to be ‘sent to Coventry’. No one will talk to her until she has found her way back into a recognition of what it means to be one girl among others, all equally real. An instinctive, untheoretical moralist, Blyton would never have put it quite this way. I borrow the phrasing from Iris Murdoch, a novelist and philosopher who wrote for grown-ups. I discovered her work studying philosophy at university, admired its gentle, enigmatic wisdom, and didn’t deplore – as many academic philosophers do – the apparent lack of arguments in her prose, perhaps because I had already been primed to recognise their truth. It was, again, as Bennett put it, as if a hand had come out and taken mine.

Time and again, the girls must be brought to their lowest ebb before a glimpse of self-knowledge and the chance to get back on their moral feet

‘Love,’ Murdoch wrote in an essay called ‘The Sublime and the Good’ (1959), is ‘the extremely difficult realisation that something other than oneself is real.’ At various points in her school career, Darrell feels this difficulty. Told by her friend Sally that: ‘All you do is put yourself into the place of the other person, and feel like them … That sounds muddled – but I can’t very well say exactly what I mean. I haven’t the words,’ Darrell responds: ‘Oh, I know what you mean, all right! … get into somebody else’s skin … But I’m too impatient to do that. I’m too tightly in my own skin!’

The schoolgirl’s hell is not, as a character in Jean-Paul Sartre’s play No Exit (1944) memorably puts it, other people; her hell is the isolated self, incapable of getting outside itself. Time and again, the girls must be brought to their lowest ebb (ostracism, betrayal, near-fatal illness or, worse, near-expulsion) before they are offered a glimpse of self-knowledge and the chance to get back on their moral feet. Sometimes an apology will do it, or an acknowledgement, or some gesture of recompense to those harmed. But Blyton, like life, can be brutal: not every character is redeemed by the end of the series, and no character is straightforwardly rid of her vices. There is only the lifelong challenge of acknowledging the reality of other people.

The most purely enjoyable of the books is In the Fifth at Malory Towers (1950). Darrell, now aged 16, must write the script for the school Christmas entertainment, a pantomime Cinderella. She is nervous – Darrell has never written anything so ambitious before, but has a sudden flash of partial self-knowledge. ‘“It’s wonderful!” she said to Sally. “I didn’t know I could. I’m loving it. I say, Sally – do you think, do you possibly think I might have a sort of gift that way? I never thought I had any gift at all.”’

Producing the pantomime turns out to be hard work – so many girls, so many egos. There’s bossy Moira who wants to call the shots and Gwendoline who won’t make the slightest effort. But Darrell’s exasperation turns into an epiphany: ‘Well, it took all sorts to make a world, and there was a place for the Moiras and Gwens…, thought Darrell.’ It takes all sorts to make a world – the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein loved the phrase when he first heard it from his Cambridge cleaning lady. He thought it ‘a most beautiful and kindly saying’. It is beautiful, and kindly, and generous, and surprisingly difficult to live out.

Like other writers in her genre, Blyton certainly valued sporting ability and physical fitness – the girls who find favour with her are the ones who like swimming, lacrosse and long walks along the Cornish coast. But she didn’t condemn the nonconformist: the girl who prefers horses to people, or maths to lacrosse. Indeed, her highest approval turns out to be reserved for the girl who wants to be a writer. ‘It takes all sorts to make a world’ is the ethic of the novelist.

Malory Towers was an early immersion for me in what the schoolmen call female subjectivity. The books threw me into a fictional world where being a girl was normal and fun. I’m not sure they converted me to feminism, exactly, but all that time spent with the idea of girls as agents certainly made it harder to see women as objects.

Blyton didn’t convert me to that awful thing, Anglophilia, either. The first Malory Towers book was published in 1946, the last one in 1951; there is no reference in any of them to Empire, and the closest they come to jingoism is in their light-hearted ribbing of their few non-British characters: the prima donna-ish visiting American and the two Mam’zelles, French teachers who get to be the target of more than one clever prank.

Blyton’s vision of Britishness in these books is instinctively post-imperial. The ‘good-hearted and kind, sensible and trustable’ women Miss Grayling wants to turn out are never going to be memsahibs; the white woman’s burden is best left to the frightfully pi. Blyton’s fiction more generally, with its wishing chairs and enchanted woods, its fairies and brownies, its hidden coves and treasure islands, belongs to a heterodox, proudly minor, idea of Britain. Britain to my childish mind wasn’t the imperial metropole but a place of weird, prehistoric magic.

One way for the ex-colonial to be post-colonial is to stop letting colonialism be the only measure of our attention

Central London – all statues and imperial war museums – came as a rude shock to me when I first visited. Well, the statues and the wars are part of the truth about Britain and there’s no point pretending it’s all faraway trees and pixie dust. But what does one do with this truth? When I first came to Britain for university, a friend showed me a poem by the US poet Jack Gilbert, ‘A Brief for the Defense’ (2005), a line from which I’ve made into a sort of personal talisman: To make injustice the only measure of our attention is to praise the Devil.

Doubtless everything’s political. But it doesn’t follow, and it isn’t true, that politics is the measure of all things. Politics, like dust, is everywhere; but there are other things in the world, nicer things, and to attend to them we have to ignore the dust awhile. This is a kind of political view too, just one that puts politics in its place. The opinion pages of the newspapers are full of vulgarians who spend their days drawing up balance sheets for colonialism – railways on the one side, famines and massacres on the other – as if what we need is a moral bottom line to save us the trouble of telling the full, messy story. I reckon that one way for the ex-colonial to be post-colonial is to stop letting colonialism be the only measure of our attention. The thing is not to gawp, in admiration or horror or awkwardness, at that history, but to find ways of putting it to use.

I didn’t go to Britain expecting it to be like Malory Towers (I had read other books by then). Even so, my first glimpse of a game of lacrosse – between two teams of hulking Canadians – was a far cry from the relatively sedate sport I had pictured. But then I found that there was one thing on which Blyton had been entirely truthful. The south-eastern coast of England, where the books are set, is exactly as Blyton describes it. A few minutes’ walk away from a village of pensioners, and there they are: the off-white cliffs, the uninviting beaches where children still go fossil-hunting and groups of doughty grey-haired women walk in the cold and rain clutching their Ordnance Survey maps. This Britain I could live with, only half-tamed, surrounded by a sea of greater antiquity than any empire.

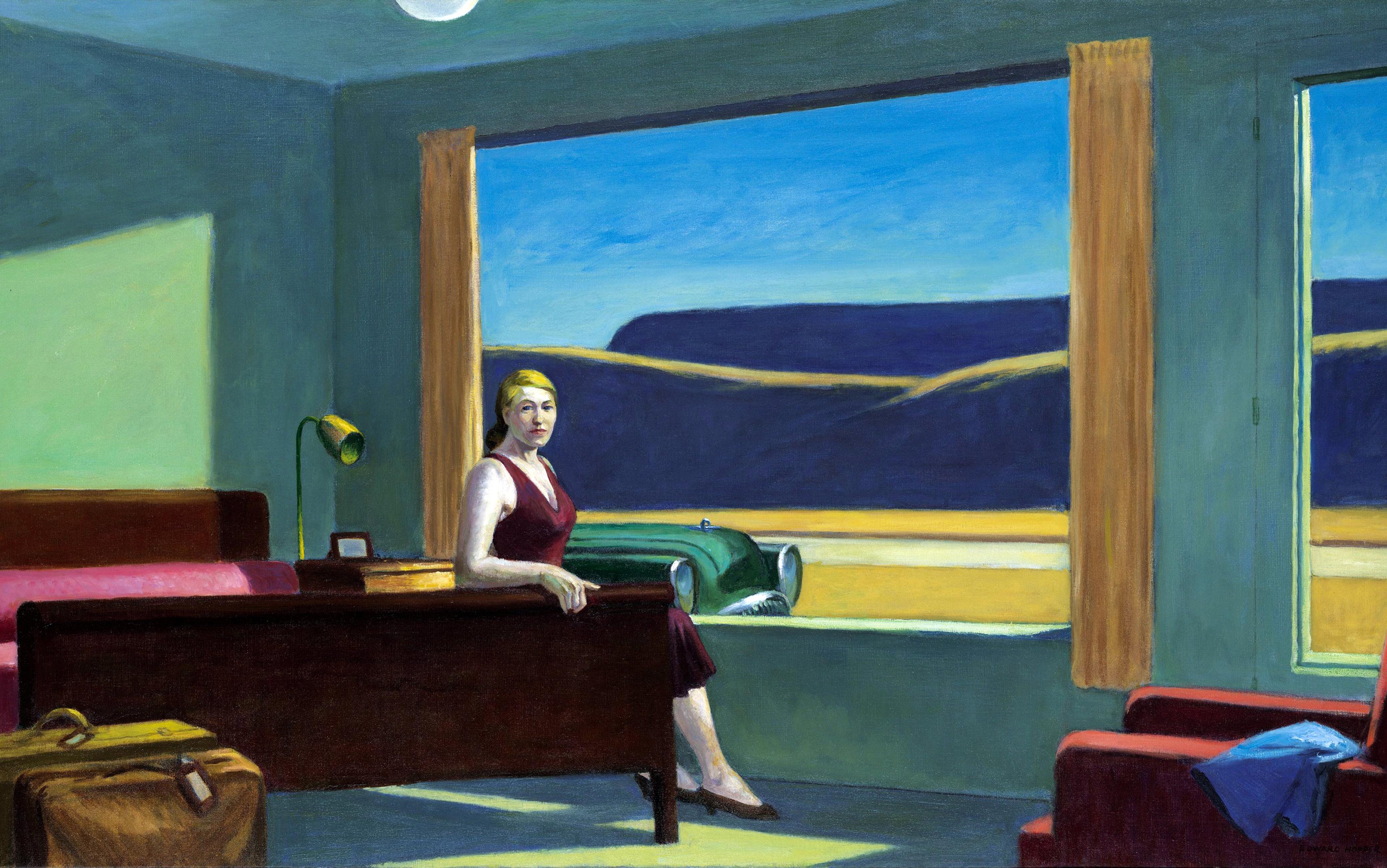

The most compelling image in the Malory Towers books is that of the school swimming pool, hollowed out of a stretch of rocks down by the sea: ‘Seaweed grew at the sides, and sometimes the rocky bed of the pool felt a little slimy. But the sea swept into the big natural pool each day, filled it, and made lovely waves all across it. It was a sheer delight to bathe there.’ For years, the thought of the pool filled me with conflicted longing.

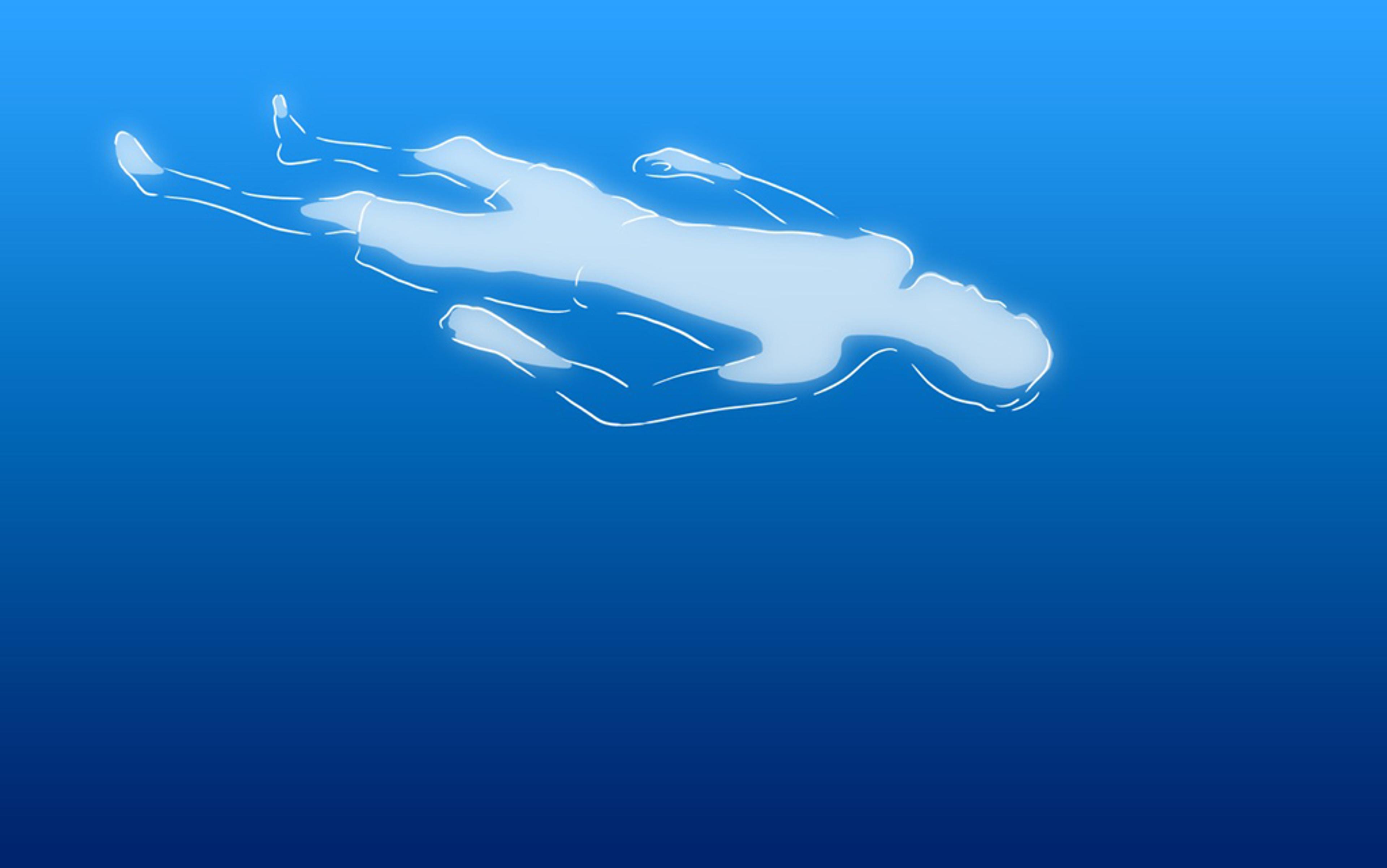

Bookish, gauche and deeply self-conscious, I’d got through adolescence adamantly refusing swimming lessons. The fact became a persistent source of guilt, putting me as it did among the Gwendolines of this world, shivering awkwardly at the water’s edge afraid to plunge in. I resolved in my early 20s to learn. It took me a year of mortifying, repetitive lessons in the university pool, surrounded by competitive swimmers doing an effortless butterfly-stroke, before I could complete a respectable length.

A couple of years ago, a friend of mine asked me along to a weekend on a campsite by a beach in Dorset, not far from the rock-pool thought to be the inspiration for the Malory Towers swimming pool. It was late summer, that cruellest of British fictions. Early that chilly morning, the party scrambled down the sandy path to the water. We had our swimming things on, but kept our beach towels wrapped tight around us against the wind, carrying bags of woolly jumpers for when we got out.

I stood on the sand, let the waves lap at my feet for a minute. No one wanted to be the first one in. But then I heard the voice of jolly, sensible Darrell Rivers in my head, bemused at the girls who fear the cold water: ‘But that’s what’s so lovely about the water … If you could only make up your minds to plunge in instead of going in inch by inch, you’d love it.’

I took a deep breath and leapt. Darrell was right. It was lovely. I swam a little way out, a bobbing speck of brown amid the grey-blue waves, looked back on the curving shore, and shouted out to the others to plunge in. It was almost too much to take at once – this sense of Britain as a little magic island, this sudden consciousness of my body as a source of joy rather than shame, and the strange, deep knowledge of being one frolicking person among others, all equally real.