I’ve been haunted for some time by an expression in The Fall (1956) by Albert Camus that goes: ‘After a certain age, each man has the face he deserves.’ The idea makes me instinctively scan all the faces that I’ve seen in my life so far. My neighbour growing up, ‘Mister Bruce’, who smoked weed all day and told us stories about the Watts neighbourhood in Los Angeles. His son Daveon, a Crips gang member, who once showed me and my brother where the police shot him in the ass when he was fleeing arrest. Kendrick, a class clown against whom I had my first street fight, and who died a few years ago in a drug deal gone wrong. All of these faces, their subtlety and nuance fading in my memory such that only the most intense aspects remain.

On the corrections bus, it’s hard to see people’s faces. They hang their heads on their chests, examining the new shackles – wrist to wrist, around the waist, down the back and each ankle. The cuffs couldn’t feel more foreign on your body, rigid and tight and biting into the skin. It doesn’t matter how many times you’ve been cuffed before, each time you get the feeling they don’t fit right.

Arlington, Texas, skating past the window, is one big consumerist amusement park. It’s all strip malls, dive bars, pawn shops and strip clubs, wavering in the unforgiving heat. The juvenile facility we’re destined for is in Fort Worth; when the bus hits the highway, the neons from the roadside restaurants can be seen all at once, a glowing line to the horizon. They’re all slightly different versions of the same thing – sports bars, Mexican restaurants, fast-food chains – yet they look so inviting from the vantage of someone in chains. I quietly resolve to go to all of them when I get out, and I don’t care how long it takes. I want to know what people in there are bullshitting about, what’s on their TVs, what their salsa tastes like. But the bus keeps going.

It’s funny to appreciate a city from a jail bus, because it’s that very city that’s sending you away. And I mean all of it is sending you away – from the disciplinarians that fancy themselves educators, to the bullshit jobs that treat you like a crook from the first day, to the police who menace you everywhere you go. The city taught me the survival mechanisms it would ultimately punish me for. There’s no other way to understand it.

My earliest memories of my late father are his lessons in how to fight. He himself was born into a violent home, taken into care, and sexually assaulted by his first foster parent. My dad knew the world he brought me into, and he knew what it would take to survive it. He’d teach me what to do when facing multiple people (line up and get your back to a wall), when someone has a knife (wrap your jacket around your arm and don’t fight close), when they’ve got a bat (wrestle), or if they pull a gun on you (rush at them immediately). I used each of these lessons before I got to age 16. My brother Austin and I would sometimes box all night, in front of the blue light of classic fights on TV. Years later, when my dad was at his most frail, in the morphine wasteland of his mind in the months before he died, he’d pass me in the hallway of our duplex that he called ‘the rathole’, bring his fists tight to his ears and do a little Muhammad Ali shuffle, saying: ‘What you got, sucker?’

The bus bounces along the highway. I wonder what the sight of the city is summoning up for my fellow offenders, who have also turned their stone faces to the window. The first time in jail, a lot of people are surprised to see so many faces they know in there. Maybe you don’t know these folks directly – they’re from two blocks over, or so-and-so’s older brother, or the cousin of someone you knew from school detention.

Prison actually feels a lot like school: students and inmates walk single-file on the right, teachers and correctional officers (COs) move freely along the left. Like when you’d walk into school and submit to metal detectors, locker searches and police sweeps of the classrooms. Every now and then, one brave student would ask to go to the bathroom, and run down the hallway beating on doors and hollering that a search was coming. The room comes to life as kids try to stuff weed, lighters and knives down the front of their pants. Even those with nothing to hide would pantomime the actions to pretend to be having these problems as well.

Because of a series of riots and a few stabbings, my high school instituted an ID policy for all students, the first in the district to do so. Surveillance by security guards added to the inmate feeling. They’d rack you up and report you to the assistant principals, who’d pull the security tapes and make you agree in writing that you did wrong. We never forgot the presence of the cameras. We’d schedule fights after school, or pile into the bathroom and man the doors to slug it out in a free period. Or people would crowd around the vending machine before kicking it in and grabbing all the gum and Gatorade. Jail is just like this. Long days of empty time and harassment, with only violent outbursts to break up the boredom.

These days I’ve got no patience for middle-class white kids who get all worked up about injustice in an abstract register. Where have they been? I’d spend the night at a black friend’s house and see that there was a qualitative gap between being poor and being black and poor – and not because they had less than my family, but because they were able to negotiate despair with much more grace and poise than us. I knew that the world was racist, not because Mister Jeb down the street would say vile things about black people, but because my black friends sang louder in church and laughed harder at the macabre truth of a system stacked against them. For years I’d watch as every authority figure – from teachers, principals, police and COs – came down harder on my black and brown homeboys, harder than on me, for things we all did together.

Children are not ignorantly going through the motions. We know who has subsidised lunch, we know who wears the same clothes every day, we know who is getting beat up at home, who takes cold showers, who is constantly asking for change to buy cookies. If you walk into any grade school in the US, I guarantee that the children there have a lucid understanding and working taxonomy of the haves and have-nots. I promise also that this taxonomy maps onto whom the teachers treat as lost causes, hell-bent on disrupting their classes, and who has a real shot at going to college. These are the two institutions available to many young people in the US today: university or jails, professionalisation or criminalisation, pantomimed autonomy or arrest.

We arrive at the juvenile detention centre on Kimbo Road in Fort Worth just after sundown. I can feel my chest tightening; adrenaline is coursing through my body. Unlike a school bus, as we pull into the garage, everything is dark and quiet. So dark and so quiet that every noise jars me: the gate slamming behind us, the pressure release of the bus doors as they open. They ring out as single sensations freed from context. After cutting the engine, the driver declares: ‘Nobody move a muscle. We will move you from here on out.’

The booking bench at a youth detention facility.

We’re led in single file from the bus to the building, in silence. When the doors swing open, I can hardly see for the flood of fluorescent light and white walls. It reminds me of every emergency room I’ve ever been in: blinding light when I had my teeth knocked out, blinding light when I split my head open, blinding light when I broke both of my hands in a fight. The jail feels like a mash-up of hospital, school and factory.

They sling you this way and that: an entire masculine performance to demonstrate who’s in charge

I could see the other inmates trying to make sense of this new light, as I was. The shock was wearing off as our backs hit the wall for a line-up. The prison officers started reading off everyone’s charges out loud, going down the line. I was facing a double felony: organised crime, and breaking and entering. Half my crew was there with me. Two of them shared my charges, the other two mysteriously had misdemeanours. When I first heard that, it was like a wire pulled so tight behind my eyes that I thought it was going to snap. Even now, against the wall, I was clenching my jaw at the thought of catching them on the outside as soon as I could.

The pigs are already setting the tone in the line-up. Macho bullshit. They search you extra hard, get you to strip, and sling you this way and that while you’re still cuffed. This entire masculine performance is supposed to demonstrate who’s in charge, though it’s seen by inmates as ridiculous and clownish. One CO keeps mushing my head into the wall while searching my naked body, saying: ‘Organised crime? So, you think you’re a tough guy?’

Even as a teenager, I’m not new to this. If you’re poor, black, Latinx or Arab, you learn early that the state will put its hands on you. It will try to humiliate you, provoke you into sabotaging yourself, deprive you of food and then smack your hand when you steal. It will tell you to toughen up, only to call you an animal, and in every possible way punish you for the ways in which it has failed you.

The first cell you sit in at Kimbo isn’t your house, but a temporary cell you’re held in while you’re being processed. The inmates call these cells the Aquarium. That’s because it’s a long, single row of cubed cells, made completely out of Plexiglas, so you’re visible on all sides. The inside of the cell has two plastic school chairs, a beaming florescent light, and a drain in the centre of the linoleum floor, presumably for piss and blood. New inmates are in the Aquarium for up to a day or two.

A 12-year-old juvenile in his windowless cell at Harrison County Juvenile Detention Center in Biloxi, Mississippi, operated by Mississippi Security Services, a private company. There is currently a lawsuit against MSS that forced it to reduce the center’s population. An 8:1 inmate to staff ratio must now be maintained.

My cellmate and I haven’t looked each other in the face or spoken for the past five hours. It’s making me extremely uneasy. I’m afraid to doze off, or to let my guard down at all. He’s much taller than me, six foot something, a thin black kid about my age, if not a little older. He won’t stop rocking in his chair. I mean, he’s at it steady for hours, moving forward and back, and talking to himself. I can’t make out anything of what he’s saying because he’s speaking so low. Meanwhile, I’ve been fidgeting with my seat, and running my nails down the glass, and trying to hear commotion a few cells over. But here is this motherfucker with his rocking and muttering. I’m certain we’re going to fight. There’s no way to share a space that tight without so much as a ‘hello’ ending in fists.

Truth is, my celly in the Aquarium is occupying my attention because I’m excruciatingly bored. When US media paints portraits of prisons, they always focus on the gangs, the violence, the rape and the racism. All of that is there, to be sure, but those events exist as lightening-like fissures in the slow cyclone of fatigued tedium. Every tiny human interaction is invaluable as a means of breaking up the monotony of the unending hours – even eating the vile-ass food, which plops in your dog bowl and at least lets you think about it for a while. Or a CO menaces you, and you get to think about hating him or beating the pride out of him for a little while. Or your eyes search the cell over and over, looking for some catalyst for imagination or memory to fill the empty expanse of time. It would only take one aberration in the texture of the ground or glass to give you a reason to reflect, but most of the time you won’t find anything different to what you already know.

What was raw power and frustration is now the depleted motions of a 16-year-old child at the end of his rope

I have no idea how many hours we’ve been in the Aquarium together, or how much longer we’ll be there, what time it is, or even when I’ll get out of this godforsaken cell. I feel sick to my stomach from the slop we ate however long ago. Homeboy is still rocking; then he yells out: ‘Man … Fuck! Fuck this!’ and shoots up so quick that his chair bangs the glass behind him. I hit my feet just as fast and instinctively put my fists up to my ears. He’s screaming at the top of his lungs and it’s ringing my ears in the tight space. He turns and picks up his chair by its legs, so I grab mine too and put my back in the corner. To my surprise, he still hasn’t looked at me, and after all this time I still haven’t seen his face.

My guy faces the side of the glass where the guards move back and forth periodically, and starts smashing it with his chair. Over and over he swings the chair into the wall, screams beginning to crack, waver, weaken. The chair is breaking with each blow and cutting up his hands such that blood and plastic are cast in every direction. My own grip is loosening as I watch the outburst. It’s been almost a full minute. I put my chair down and hang my head, chin deep in my chest and tears welling up behind my eyes. Thirty seconds ago, what was raw power and frustration is now the sad and depleted motions of a 16-year-old child at the end of his rope. His voice is gone and his screaming has become a low, rhythmic moan. His hands are all blood, and only the seat of the chair remains in his grasp.

Six shadow-faced COs show up to the cell, fumbling with the lock. The sight gives my celly new energy, and he roars again at the glass. As the guards pour in, I remember thinking that we won’t all fit in here – but then they are standing on us, and the thought disappears. The cell extraction entails body-slamming the two of us, knees in our backs, and our faces pressed into the linoleum. We’re both hogtied. I begin to protest that I haven’t done anything, but I stop, knowing it didn’t matter. None of this matters. It’s just protocol.

Lying on the floor with my ankles tied to my wrists, I look over to my cellmate, who’s turned his head in the opposite direction. He’s crying now too. ‘I just want my mom, man,’ he whimpers. ‘My mom, man. I just want my mom.’ He says this with the same persistence as his rocking before. I can’t remember if the guards said anything back, just the screaming and the crying, the mom talk. Now they’re carrying us both by our cuffs, like luggage, out of the debris-strewn cell. The metal is digging so deep into my body that I feel like it’s going to slice through me. We’re conveyed past the main block to the segregation cells, as the other inmates begin to beat their palms on the walls of their houses, screaming: ‘Yeaaaaaaaaaaah,’ in unison, as loud as they can.

I never saw that boy again during my stay, but I was haunted by him for years. I never saw his fucking face again, and it drives me crazy. Him crying for his mom, drowned out by the screams of other boys cheering – that’s what the experience of masculinity means to me. We are crying for our mamas as we’re carried off into the callous chants of those who have strategically dulled such emotions.

In Texas jails, it’s common slang for a fight to start with: ‘You tryna’ look at it?’ Walking past someone’s cell, it’s considered extremely offensive to eyeball it. Just like in the free world, really. Lock eyes with any man in a poor neighbourhood without acknowledging him, and you’ll get a reaction. I never looked at my celly back in the Aquarium because I didn’t want to fight. I didn’t want to ‘look at it’. I didn’t want to look at him because I didn’t want to see myself: rocking, scared, violent, confused, depressed. It’s no wonder we men pioneer this fragile yet somehow metaphysical sense of ‘respect’, which we won’t suffer to be challenged. None of us look at each other long enough to really see.

Rumours have been floating about who got what time, who told the pigs what, who was going to slide on who

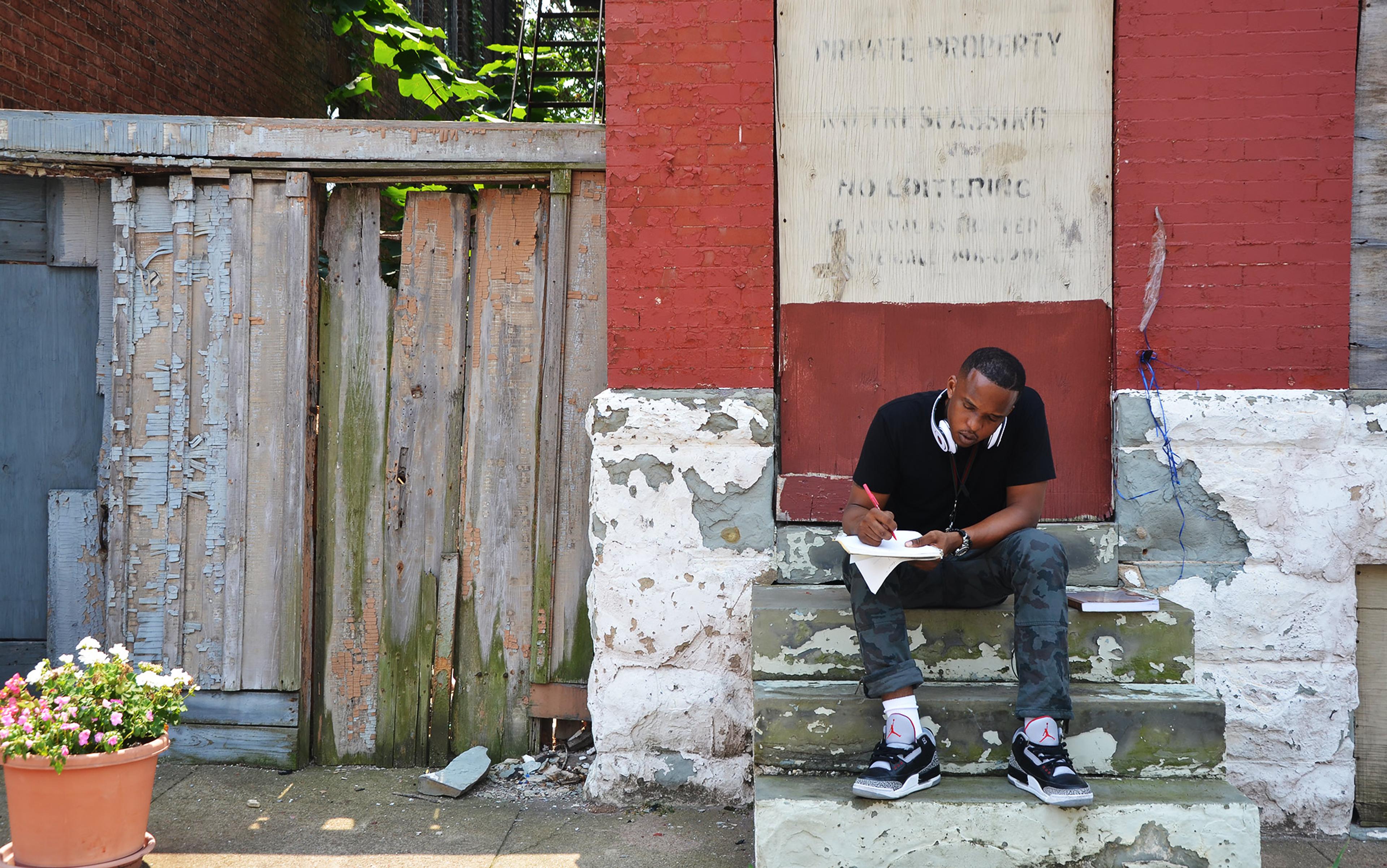

I get out of Kimbo and enter a new phase of incarceration: parole. Life on parole is as lonely as anything can be in the free world. I report in to my condescending parole officer daily, only to be lectured and admonished for a lifestyle that was endemic to my neighbourhood. Curfew is 8pm, and I have to do innumerable hours of ‘community service’, where I’m barked at like I’m still locked up. Communication with my co-defendants, and other felons, is strictly forbidden. Considering I was booked on charges of organised crime, these stipulations mean I won’t see my friends – my ‘gang members’ – for quite some time. But they’re the only friends I had.

We’re in the car one day anyway, clowning around. I’d just tried chasing down some guy, Ramone, who I was convinced is a rat. Rumours have been floating around about who got what time, and who told the pigs what, and who was going to slide on who. Now, though, we’re just listening to music and chopping it up about the usual bullshit – which dude is pussy, how big and bad we all are, standard neighbourhood mouthwashes.

A person walks in front of the parked car with a kid. We break into nervous laughter; we can’t tell if it’s a woman or a man. We decide to send in L, because he’s wearing a cast and can ask the person to sign it so we can check the name. We watch L get out and hand the person a sharpie. It turns out she’s a trans woman, and asks L if he wants her birth name or her current name. ‘Whichever you prefer,’ L says, quietly. The woman is so kind and calm, we all stop laughing and are confused and quiet together. Ten years later, L himself decides to transition, and teaches us a lot about how to think and talk about it.

Increasingly, I understand toxic masculinity as a symptom of a larger violence, a kind of survival mechanism for people who are acutely aware of the contingency of their own life. In The Will to Change (2003), the feminist author bell hooks wrote:

The first act of violence that patriarchy demands of males is not violence toward women. Instead patriarchy demands of all males that they engage in acts of psychic self-mutilation, that they kill off the emotional parts of themselves. If an individual is not successful in emotionally crippling himself, he can count on patriarchal men to enact rituals of power that will assault his self-esteem.

It would take someone much smarter than me to explain why hooks is right about this, but what I can say is that she is right about me and my childhood.

I ended up going back to county jail a dozen times over the next few years. My friends would bail me out, I’d bail them out. My homeboy would lend me money for my girlfriend’s abortion, and six months later he needed me to bail him out, and we’d call it even. A diversity of stalemates. It wasn’t until I decided to skip town and go to community college that I managed to break the cycle of arrests, petty beef and unpaid tickets. For the first time in my life, I had a purpose that wasn’t mere survival. A myriad of new problems would inevitably crop up: identity crises, fits of anxiety, impostor syndrome, naked hostility to authority. But more than anything, I felt like a clown. My heart was so heavy from living the way I’d done before. For a while, every time I showered, I’d shuffle through people’s faces that I’d ran up on or gone after, or think about the face of my dad, disappointed to learn that I’d been caught stealing clothes from a menswear house for a date. I’d cry and wish I was somebody else.

Ultimately, it felt like all the men in my life had been preparing me for a war that was never going to happen. If one of us got evicted, we’d stick our chest out and say: ‘What do you know about the struggle?’ If we got jumped and robbed, we’d look at people like: ‘What do you know about pain?’ One of our family members would die or go to prison, and it would just make us more outwardly aggressive, more inwardly empty. Turning pain into pride might release some pressure in the meantime, but it will crush you later in life. This kind of masculinity makes you an idiot, incapable of holding on to any form of vulnerability for longer than a moment. Even now, walking around, I see men avoiding each other’s glances. We never really see each other. I think inside we’re all beating the chairs against the Aquarium cell of our minds.

He had spent three decades inside. No one had asked him how he was feeling

I’ve always felt a lived negotiation between two worlds: the world of north Texas poverty, in all its violence, sincerity and sun; and the world of academia, with its irony, nervousness and fluorescent light. More of my friends went to prison than to university. Almost all of them for crimes related to poverty: robbing drug dealers, racking up warrants because they couldn’t pay their tickets, acting out when they were drinking away their suffering, burglary, selling drugs. Each of them in prison writing to their mamas, ex-girlfriends, old homeboys. Reaching out of their cells to make even a superficial connection. And when they come home, their startle-response will be like mine, exaggerated and intense. They’ll fly into fights, feel disrespected by low-paid and dehumanising jobs.

Most people don’t understand what jails and prisons do to your psyche, the kind of subjectivity such torture-houses will produce. In jail, you dream about the free world – dinner at a diner or your mom’s house, an old friendship from the playground – only to have your dream-work infiltrated by COs, prison food or would-be attackers. My younger brother once told me he’d dream about having sex, but when he’d turn to his dream woman in bed, he’d realise she was lying on a concrete bunk. In the dream, he’d panic and look around, finding himself in his cell with a CO trying to fix a broken sink. And then he’d wake up in a full sweat in his segregation cell.

Now I have a Masters degree, and I’ve been working as a community organiser, doing jail, court and parole outreach. Some of the older men coming home from 30 or 40 years in prison are talking to me within 10 minutes of being dropped off in the free world. Recently, I met a man whose hands were so swollen and stiff he couldn’t write his own name. He had just come home on life parole after three decades inside, and his eyes were far away, flickering and watery. No one had asked him how he was feeling in such a long time. He spoke softly, telling me how to spell his name and where to find him, and limped off into a city he barely knew. He is still locked up in his mind. He doesn’t have the face he deserves. He has a face no one deserves.