At 5:30am I awoke to the sound of the diesel chug-chugging of a lone lobster boat carving into the glassy Atlantic. An audience of shrieking gulls hushed in the engine’s wake as it rumbled through the narrow strait that separates the United States from Canada. After the boat pushed out into the open ocean, the gulls resumed their gossip, and I began preparing for a day on the water, still groggy from the night before, after joining a group of researchers over beer. I had come to Lubec in Maine with a bizarre question: what was 9/11 like for whales?

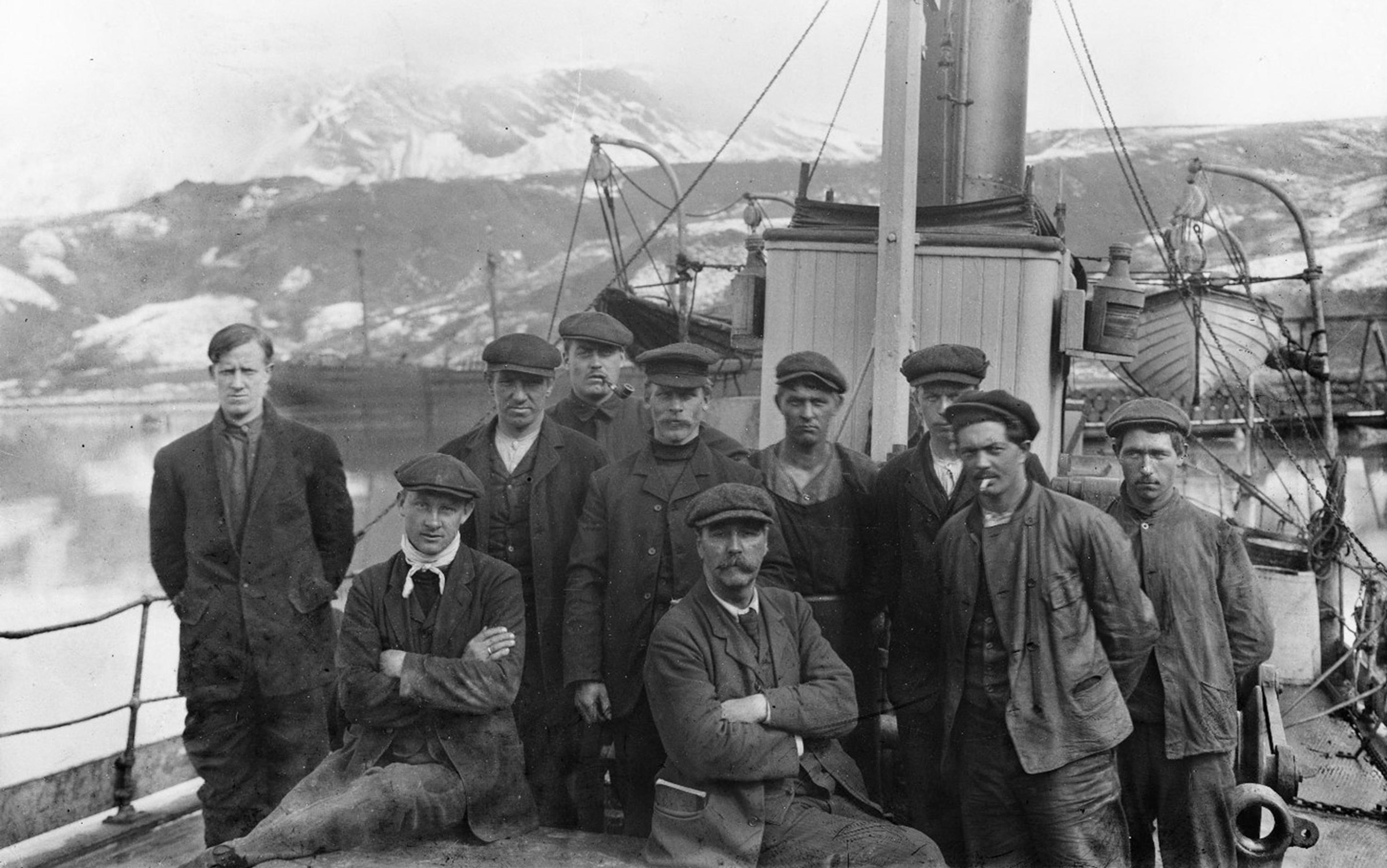

I sleepwalked to the pier and helped pack a former Coast Guard patrol boat with boxes of underwater audio-visual equipment, as well as a crossbow built for daring, drive-by whale biopsies. A pod of 40 North Atlantic right whales had been spotted south of Nova Scotia the day before and, with only a few hundred of the animals left in existence, any such gathering meant a potential field research coup. ‘They even got a poop sample!’ one scientist excitedly told me. The boat roared to life and we slipped past postcard-ready lighthouses and crumbling, cedar-shingled herring smokehouses. Lisa Conger, a biologist at the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), manned the wheel of our boat, dodging Canadian islands and fishing weirs. As the Bay of Fundy opened before us, a container ship lumbered by to our stern: a boxy, smoking juggernaut, as unstoppable as the tide.

‘After 9/11, we were the only ones out here,’ Conger said over the wind and waves. While this tucked-away corner of the Atlantic might seem far from the rattle of world affairs, the terrorist attacks on New York City and Washington DC of 11 September 2001 changed the marine world of the Bay of Fundy, too.

Conger leads the field team in Lubec for Susan Parks, a biology professor at Syracuse University. As a graduate student, Parks found that right whales were trying to adapt to a gradual crescendo of man-made noise in the oceans. In one study, she compared calls recorded off Martha’s Vineyard in 1956, and off Argentina in the 1977, with those in the North Atlantic in 2000. Christopher Clark, her advisor, had recorded the Argentine whales and, when Parks first played back their calls, she thought there must be some sort of mistake.

‘It was older equipment – reel-to-reel tapes which I’d never used before – so I went to Chris to ask if I had the speed of the tape wrong because the whales sounded so much lower in frequency than the whales I had been working with.’

In fact, Parks discovered, modern North Atlantic right whales have shifted their calls up an entire octave over the past half century or so, in an attempt to be heard over the unending, and steadily growing, low-frequency drone of commercial shipping. Where right-whale song once carried 20 to 100 miles, today those calls travel only five miles before dissolving into the din. Under the right conditions, fin- and blue‑whale song can carry thousands of miles, as Clark realised while listening in on the oceans using the US Navy’s global submarine detection network. He was stunned to hear a blue whale singer on the Grand Banks of Canada all the way from Puerto Rico, 1,600 miles away. However, it’s an open question whether these performers are actually trying to be heard by their audiences across the ocean.

‘If you have whales spending more time moving out of areas because they’re noisy, or if they have lower reproductive success because they can’t find mates, those seemingly small changes could really add up to a population-level effect where you could cause the birth rate to decline and the mortality rate to increase to the point where, eventually, the populations could go extinct,’ Parks told me.

Just how much noise has been added to the ocean has been revealed by the worldwide network of underwater microphones originally developed to eavesdrop on submarines. Hydrophones anchored to the continental slope off California, for instance, have recorded a doubling of background noise in the ocean every two decades since the 1960s. For whales, whose lives can be measured in centuries, the dramatic change to the environment is one that could be covered in the biography of a single whale. As a testament to that longevity, in 2007, during a traditional whale hunt, indigenous Alaskans pulled a bowhead whale out of the water with a harpoon embedded in its blubber that had been made in New Bedford, Massachusetts, in the 1800s – a type of weapon that might have been familiar to Herman Melville.

‘It’s very likely that the individuals that were being recorded in 1956 were the same ones being recorded in 2000,’ Parks said. ‘Some of these whales were born before there were motorised vessels in the water at all.’

Still, it’s a mistake to imagine that the soundscape of the oceans was pristine before modern man. The seas, which are poor in light, have always been rich in sound. Some of the loudest, and most alien, noises on planet Earth are known only to ocean life. Lightning strikes, for instance, are mind-bogglingly loud underwater, and utterly extraterrestrial. Unlike the dry crack of a thunderclap on land, when lightning strikes the water, the oceans echo with an astonishing metallic howl, like a phaser blast from God. The awesome roar of underwater earthquakes and volcanoes can be similarly sublime, while the groans of distant icebergs calving off Antarctica have been picked up by hydrophones more than 3,000 miles apart. Even fish are surprisingly noisy, with many – like the black drum – beating their gas-filled swim bladders to make twangy, plucking noises, like an orchestra of jaw harps. In southwest Florida during spawning season these calls can even be heard in homes along canals, when black drum chatter channels through floors and walls and into the open air.

On coral reefs, hydrophone recordings are often overwhelmed by the crackles and pops of the unassuming pistol shrimp, which slams its comically oversized claw together with such incredible force as to create a vacuum bubble in the water. When the bubble collapses, it creates fleeting bursts of sound that, in aggregate, can drown out everything else in the environment. The shockwaves from these miniature supernovae blast the pistol shrimp’s prey into submission. Some larval fish are attracted to these reef sounds – the popcorn crackle signals home.

The living world can even change how sound propagates underwater. A dense seam of small sea life exploited by diving whales and sharks throughout the world’s deep oceans is known as the ‘deep scattering layer’. It was discovered by confused Second World War sonar operators, some of whom interpreted the sonic reflection as a false sea bottom. The seas themselves can also warp the soundscape, with cold, deeper, denser water forming acoustic channels at the bottom of the ocean over which sound can travel thousands of miles, the ocean’s long-distance line. The seafloor can dampen or reflect noise depending on its composition. And at the ocean’s surface, wind, waves and heavy rain make for a roiling translucent ceiling that showers the seas in sound.

Mass strandings of more than a dozen beaked whales have happened in the wake of military exercises, with autopsies on the whales revealing symptoms of the bends

And so it was for millions of years. Now a host of strange, altogether new sounds ring throughout the ocean. Offshore oil and gas exploration, now in its heyday, uses literally earth-shaking blasts issued from airguns towed along the surface for days on end. The reports are powerful enough to penetrate the planet’s crust and bounce back to the surface, bearing the signatures of unplumbed pockets of ancient hydrocarbons deep in the rocks. The technique made headlines this summer when the Obama administration reversed a Nixon-era moratorium on oil and gas exploration on the Atlantic continental shelf, drawing outrage from environmental groups after its own summary estimated that 138,000 marine mammals could be injured from the testing.

In Parks’s career listening to the sea – an experience she likens to space exploration – the seismic survey has been a consistent if unwelcome guest in her data. ‘There were some places where 90 per cent of the time the entire acoustic recording we had was completely obscured by seismic surveys. Every two seconds there was a blast.’ In one study, recorders on the mid-Atlantic ridge picked up the rhythmic blasts of seismic surveys off the coast of Angola. That same oil and gas exploration was contemporaneous with a silencing of humpback singers.

Perhaps the most well-known collision of man-made noise and ocean life, though, is that between the world’s navies and its marine mammals. Active military sonar comes in different flavours – much of it quite unlike the rasping pings of Tom Clancy-inspired Hollywood productions. There are the plaintive howls of low-frequency sonar to the almost deliberately annoying whinnies and squeals of powerful mid-frequency sonar. Deep-diving beaked whales are terrified of the noise, which they can interpret as exceptionally frightening killer whales. Mass strandings of more than a dozen beaked whales have happened in the wake of military exercises, with autopsies on the whales revealing symptoms of the bends – a strange injury for an animal accustomed to diving almost two miles down. Other whales have been more direct casualties of war: during the UK prime minister Margaret Thatcher’s adventure in the Falklands in 1982, two right whales – perhaps ones recorded by Clark – were mistaken by sonar operators for a pair of submarines and torpedoed by the Royal Navy; another was attacked by the ship’s helicopter.

These dramatic encounters with the military read like environmentalist fever dreams, which is why they inspire headlines. But the more humdrum machinery of the global economy probably poses a larger threat to marine life.

‘A cargo ship is basically like a large rock concert passing by,’ said Jesse Ausubel, the director of the Program for the Human Environment at the Rockefeller University. I met with Ausubel in his house in Oak Bluffs on Martha’s Vineyard, where the dining room was decorated with a sawfish rostrum and Newfoundland placemats, and the conversation was peppered with anecdotes reflecting a life spent far afield, exploring undersea volcanoes in Montserrat and coral reefs in New Caledonia. Ausubel was the co-founder of the Census of Marine Life, a $650 million dollar, 10‑year, 80‑country project to document all the life in the ocean. It identified a quarter-million organisms, including Dinochelus ausubeli, a chopstick-clawed lobster from a deep sea trench off the Philippines named for Ausubel. He suspects there might be another 750,000 more species that await discovery.

‘Until 2010, there wasn’t even a list of what lives in the ocean,’ he told me. If the roll call of sea life is still being tallied, man’s acoustic effect on it is even more of an unknown. For Ausubel, ‘What struck me the most about the sound issues that came up during the Census of Marine Life was the total lack of baseline information.’

In 2011 Ausubel, along with more than 20 other authors representing research institutions, nonprofits and even military and shipping interests, formally proposed the International Quiet Ocean Experiment (IQOE) in the journal Oceanography. For the past few years, the diverse group has been meeting around the world to plan the experiment, which is envisioned as a 10-year project that shares a scope similar in ambition to the Census of Marine Life. Along with co‑ordinating government, industry and academic research on anthropogenic noise and its effects on marine life, the IQOE also puts forward a bold and evocative proposal: at some point in the near future, turn off all the sound in the ocean and see what happens. The group sensibly notes that the smaller bodies of water would be more practical venues for the experiment, and that a global quieting of the oceans would be ‘nearly impossible’. Still, Ausubel is optimistic.

‘I think it’s not a completely crazy idea,’ he told me. ‘What I’d like to do is have a period of let’s say four to eight hours in which we really, really try to remove as much sound as possible. The intuitive idea is to take a time like Christmas Day or New Year’s when people are doing less anyway.’ But even if the IQOE managed to stop all shipping, offshore drilling and naval exercises for an entire day, it still wouldn’t be long enough to let the oceans stop ringing with the echoes of man-made sound.

‘Still, if you could stop things for eight hours you really would have a pretty major global effect,’ he said. Perhaps fish would begin schooling differently. Perhaps whales would start talking in bygone frequencies now hogged by the tens of thousands of container ships on the open seas.

Ausubel thinks that the issue of man-made sound in the ocean doesn’t have to be one of environmental gloom and doom. Some solutions are already available, such as requiring sound insulation for offshore rigs, developing quieter propellers, changing shipping routes, and timing noisy activities to occur when seasonal migrations carry vulnerable animals away from the clamour. The oceans could be zoned for noise. It’s a path that some organisations, such as the NOAA are already charting.

But in the meantime, Ausubel says, human additions to ocean noise are about equal to natural noise for the first time. ‘And the human additions are going up,’ he said.

It turns out that an experiment of the sort Ausubel and his colleagues are proposing has already been carried out, though this one was unplanned. Back in the Bay of Fundy, we skipped past the cliffs of New Brunswick’s Grand Manan Island and dipped over the horizon, out of the sight of land. Before long, 25-foot basking sharks leapt out of the water and flailing mola mola wandered uneasily towards our propellers. A line of dolphins broke through the glinting surface. Fin, humpback, minke, sperm and right whales surrounded us, spouting, breaching and lazing in the sun. Underwater, the team’s hydrophones revealed a collage of clicks and inquisitive bloops, as well as the unmistakable hum of distant propellers.

The melancholy days after 9/11 on the Bay of Fundy were a brief return to life in the pre-industrial oceans

By the end of the day, I was struggling to understand how the humpbacks we had just witnessed diving for herring found their food.

‘We don’t know how any of ’em find anything,’ Conger said as we pulled back into Lubec in the afternoon, sunburnt and salt-sprayed. ‘How do right whales find a big cloud of copepods in the middle of the ocean? It’s a mystery.’

In September 2001 Parks was working to shed light on part of this mystery, recording the soundscape and trying to decode the social calls of right whales. In the chaos of the days that followed the 9/11 attacks, Parks drove home, but those who stayed behind carried on her project.

‘Scott Kraus [a researcher at the New England Aquarium] called me from the field saying, “You have to listen to these recordings – we’ve never heard anything like it,”’ Parks told me. ‘It’s like you could hear a pin drop.’

The march of commercial shipping had come to a halt as the world recoiled from the dreadful spectacle of crumbling skyscrapers and plane-shaped earthen scars. But underwater, the acoustic fog that had settled on the oceans for decades had lifted. The researchers found themselves in the middle of an unprecedented, if tragic, experiment. The melancholy days after 9/11 on the Bay of Fundy were a brief return to life in the pre-industrial oceans. As Parks’s team was recording the marine soundscape, Rosalind Rolland of the New England Aquarium was collecting faecal samples – floating whale poop – and measuring them for stress hormones. While Parks’s recordings testified to an ocean silenced by tragedy, Rolland found that the whales’ stress hormones had plummeted as well. The whales, it seemed, had finally relaxed.