A frayed leather wallet. A broken watch. Some coins. A ballpoint pen missing a screw. For 11-year-old Maddy Reid, this was all that remained of her soft-spoken accountant father … an assortment of 59-year-old George Reid’s meagre belongings emptied onto the kitchen table. ‘It’s gruesome, I know, but I think they still had his blood on them.’

And then there was the music; those hauntingly familiar tunes. ‘For years growing up, there were songs that immediately made me think of him,’ said Maddy, now a 49-year-old artist living in Cornwall. ‘Like, this is going to sound ridiculous, but you know that old song Big John? It’s such an old one, a Western. Dad grew up in Belfast but he was born in Georgia, and he seemed to have an American influence in his musical taste.’

On 25 March 1980, Maddy and her brother, Philip, 14, had just got home from school when there was an unexpected knock at the door. There, were two policemen, solemn-looking, hats removed, asking to speak with their mother. ‘You just think, what’s going on? What’s this about?’ said Maddy. ‘Mum goes into another room with them. They leave, she comes back into the kitchen, sits down at the table and – I’ll never forget this – she has that clear plastic bag with my dad’s stuff in it. “Right,” she tells us. “Your father’s dead. He’s killed himself. He jumped in front of a train. Here’s what he had on him.”’

It was the only time her mother would ever speak openly of her father’s suicide.

Globally, close to a million people a year kill themselves, and many times that number attempt to do so but fail. That’s a conservative estimate, too; for reasons such as stigma and prohibitive insurance claims, suicides and attempts are notoriously underreported when it comes to the official statistics. Roughly, though, these figures translate to the fact that someone takes their own life every 40 seconds. Between now and the time you finish reading the next paragraph, someone, somewhere, will decide that death is a more welcoming prospect than another breath in this world, and will permanently remove themselves from the population.

The specific issues leading any given person to become suicidal are as different, of course, as their DNA – involving chains of events that one expert calls ‘dizzying in their variety’. But one sobering fact never varies: many of these people are parents. Some, to young children. For a vulnerable kid trying to make sense of such a catastrophic loss, it can be devastating.

Compared with those who’ve lost a parent to other forms of sudden death, children bereaved by suicide are more likely to suffer adverse outcomes. Many of these, such as drug addiction, relationship problems and their own suicidality, are lifelong issues. The prognosis is especially dire for those who aren’t provided appropriate support, or for whom a conspiracy of familial silence hangs over the suicide, as though it is something to be ashamed about.

This sense of being judged about suicide isn’t just the imagination of oversensitive survivors, either. It’s empirically real. Back in the 1960s, the American psychologist Richard Kalish administered a ‘social distance scale’ to measure college students’ prejudicial attitudes towards a real hodgepodge of stigmatised communities. One of the questions in the scale was: ‘Would you willingly go out on a date with [this type of person]?’ Participants were more willing to date someone dying from cancer, or members of a marginalised ethnic or religious group (in this old study, black people, Mexicans and Jews), than they were to date someone who’d attempted suicide. On the other hand – and I’m not sure if this qualifies as good news, exactly – they were more willing to go out on a date with a suicide-attempter than a Nazi.

And when Kalish’s study was replicated 25 years later by the psychologist and suicide expert David Lester in New Jersey, the trends were identical. Furthermore, when asked: ‘If you really loved him/her, would you marry someone who had attempted suicide in the past year?’ only 33 per cent of people said yes.

Such findings might sound reasonable for pragmatic romantics (after all, the best predictor of suicide is a previous attempt and, all else being equal, giving one’s heart to someone at significant risk of suicide is a high-stakes emotional wager). However, since such prejudice can extend to the close family members of those who actually die by suicide, it’s easy to see why so many are wary of acknowledging the suicide of a parent. One woman who’d lost her father to suicide six years prior wondered aloud: ‘Will the stigma be attached to the children, to the children’s children, and to their children in turn?’

Yet such silence, no matter the intention, comes at a cost for children scrambling to repair the sudden rift left by a parent’s unexpected, and deliberate, exit from everything they know. In the bereavement literature, suicides are often linked to symptoms of ‘complicated grief’: a medical term that refers to grief and mourning that lasts longer than six months and significantly impairs the individual’s daily functioning.

‘She didn’t come out and say we’re not allowed to talk about your father,’ explained Maddy about her mother’s handling of the situation. ‘But it was made clear that it was a taboo subject, and we were to build a wall around ourselves and forget about it. It was horrendous, because the support just wasn’t there … She went through and burned all the old photos. She just wanted “it” gone.’

Maddy’s experience as a shellshocked young girl attempting to come to terms with her beloved father’s suicide, yet deprived of a healthy conversational outlet to do so, appears to be common among those who lose a parent this way. Research on the emotional impact of parental suicide is surprisingly slim, with much of the literature tending to focus on suicide bereavement in the opposite direction (parents grieving the suicides of their children). But one researcher, the American psychologist Albert Cain, has studied parental suicides extensively. And he’s identified recurring themes surrounding what he calls ‘the telling’, which is essentially the story given to the child by the surviving parent or guardian.

Most clinical resources stress the importance of being direct and honest with children about a parent’s suicide, but Cain argues that there’s no one-size-fits-all approach. In contrast to Maddy, who learned the basic facts about her father’s death, the overwhelming majority of children are led to believe, at least initially, that the death was by some means other than suicide.

The reasons for this are many. Sometimes the child is simply too young to understand what suicide means, or perhaps the child’s immediate worries and thoughts are more practical – ‘Who will walk me to school? Who will make dinner? Will we have to sell the house and move?’ and so on. ‘At times, knowing the exact nature of a parent’s death is well down the list of bereaved children’s felt needs and concerns,’ explains Cain.

It’s easy, of course, to say that it’s always best to tell the child that it was suicide. But every family dynamic is different. Sometimes, the surviving parent must come to terms with the suicide in their own right before communicating it in a healthy fashion.

‘Much as I and the kids loved her,’ said one widower justifying his delay in telling his children that their mother had killed herself, ‘I hated her guts that much, maybe more, doing that just a day before our oldest’s birthday. [If] I’d have told the kids back then what she really died of, what she did to us, I’d have wiped her out – they’d either hate her forever, or me, or both.’

The telling must involve retelling. It’s a process, not an event

From interviews with adult survivors such as Maddy, it’s clear that the telling casts a permanent shadow on the child’s understanding and interpretation of the loss. When a caregiver, seething with anger, curses and blames the deceased, the narrative communicated to the child implies the suicide’s deep moral failure, an archetypal tale of cowardice, selfishness and weakness. It’s a toxic message, especially for children who continue to identify closely with the dead parent. Although often understandable, says Cain, such barbed tellings are ‘less an explanation than an indictment, a bill of particulars against the deceased’.

Not infrequently, this occurs in the guise of religion, with the grief-stricken spouse committing the other to hell for the ‘sin’ of suicide. ‘No, your mother’s not an angel in heaven now,’ one father told his kids. ‘She’s just dead. If she loved us, she would have stayed with us, not copped out. God didn’t do it, Mom did.’ Young children, of course, cannot interrogate such wobbly theological claims. They cannot ask, for instance, why a God who doesn’t give us anything we can’t handle apparently did just that to their mom or dad.

Even when such moralistic blame isn’t a factor, however, a sense of dismissiveness might creep in, whereby the event is minimised or discounted as something beyond human purchase. When the telling isn’t elaborated with an ongoing effort to understand the suicide, the information alone, just dropped on the child, can fester. The telling must involve retelling, incorporating developmental changes and life experiences that enable the child to process it again and again, to make new meaning in light of new understanding. It’s a process, not an event. In Maddy’s case, her mother was blunt and forthright, but there was no story. Cain writes:

[Some] are relatively quick and clear in letting their children know the death was a suicide, yet … refuse any further discussion. They reported that they met questions from their children with stern if not angry rebuffs: ‘I don’t know, I wasn’t in her head…’ ‘Don’t ask me, we’ll never know,’ ‘There’s no use thinking about it, we have to go on with our lives,’ ‘He’s dead, and he has all the answers.’ Ordinarily a few brief, charged exchanges like these put an end to overt questions, leaving the child to his or her own constructions, patching together fragments of information and fantasy or joining an alliance of suppression.

One of the more heartbreaking outcomes in young children are re-enactments of the parent’s suicide in spontaneous play. One team of clinicians writes about a little boy who, in the wake of his father’s suicide by hanging, plays a game in which he hangs all of his teddy bears from the banisters. In older children and teenagers, such outward signs might be less apparent, but their ruminative visions are disruptively dark and unnerving. ‘Even now,’ Maddy told me, ‘I can’t help but picture the event. You can’t stop it. You’re picturing him jumping. You’re picturing the aftermath.’

By age 13, Maddy would find herself battling those dark impulses herself. Identifying more with her quiet and contemplative father than her matter-of-fact mother, for years she was secretly riven with guilt over his death. Her parents’ marriage had fallen apart two years before the suicide; in desperate straits, her dad had taken out a room at the YMCA, 10 miles up the road. ‘I’d spoken to him a few days before he killed himself. I’d said to him – not understanding how bad off he was – “Daddy, I want a pony for my birthday. Do you think you’d be able to?” That’s all I remember about that phone call. So it’s a guilt thing. I think: Jesus, did I push him over the edge, pressuring him to get me a bloody pony?’

In fact, many children attribute the suicide to something they’d recently done to upset the parent. A bad report card, coming home late, ‘costing too much’, ‘getting another bad cold’ … such last-straw explanations feature prominently in children’s accounts. On the morning of her mother’s suicide, one eight-year-old girl had shouted that she hated her mother. ‘The ferocity of their guilt [is] fully attested by their absolute insistence, in the face of therapists’ interpretations and reality confrontations, that it was their fault,’ writes Cain.

Particularly guilt-inducing are cases in which the child had been tasked with monitoring the suicidal parent when it happened – ‘Call Daddy right away at the office if Mamma seems real upset’ – or discovered the parent while he or she was still alive but couldn’t get help quickly enough to save them. Some actually bear witness to the parent’s suicide, or at least to some aspect of it. Rather astonishingly, in about a quarter of even these cases the child is told that the death was due to an accident or illness. ‘A boy who watched his father kill himself with a shotgun was told later that night by his mother that his father died of a heart attack,’ notes Cain. ‘Two brothers who found their mother with her wrists slit were told she had drowned while swimming.’

In other situations, the child is spared from exposure to the act itself, but the living parent is adamant that the child not be told of the suicide. Still, children are surprisingly adept at puzzling it together. A seven-year-old girl told her therapist: ‘You know, my daddy killed himself,’ before sharing with him more detailed information about the suicide than even the mother had given him. She leaned forward, fingers to her lips. ‘Shhh,’ she whispered. ‘Don’t tell Mommy, because she thinks Daddy died in a car accident.’

Of course, it’s complicated. Occasionally, it’s the child who refuses to accept that it was a suicide, to grapple with the implications. ‘You don’t know he didn’t fall asleep in the car,’ said one teenager whose father died of carbon-monoxide poisoning. ‘They broke into his hotel room to rob him. They shot him,’ said another.

The message is that this wasn’t a conscious rejection, but a bodysnatching presence driving a splitting wedge

‘Children’s refusal or inability to hear can exist quite independently of parents’ refusal or inability to tell,’ writes Cain.

Avoidance of the truth is often motivated by the surviving parent’s difficulty in providing an age-appropriate reason for the suicide. And who can blame them? Explaining to a young child, or even a teenager, why the parent ‘chose’ to die in such a jarring fashion is daunting. Many rely inventively on sickness metaphors to guard against the child’s powerful sense of rejection and abandonment. Likening mental illness to a flu, one mother told her small daughter that her daddy didn’t want to kill himself but, like vomiting, he just couldn’t keep it from happening. ‘Another,’ writes Cain, ‘reminds her son of his chicken pox, and how at its worst he scratched even when he was trying so hard not to.’ In other words, the message being imparted is that mommy or daddy didn’t want to leave you – this wasn’t a conscious rejection, but a bodysnatching presence driving a splitting wedge.

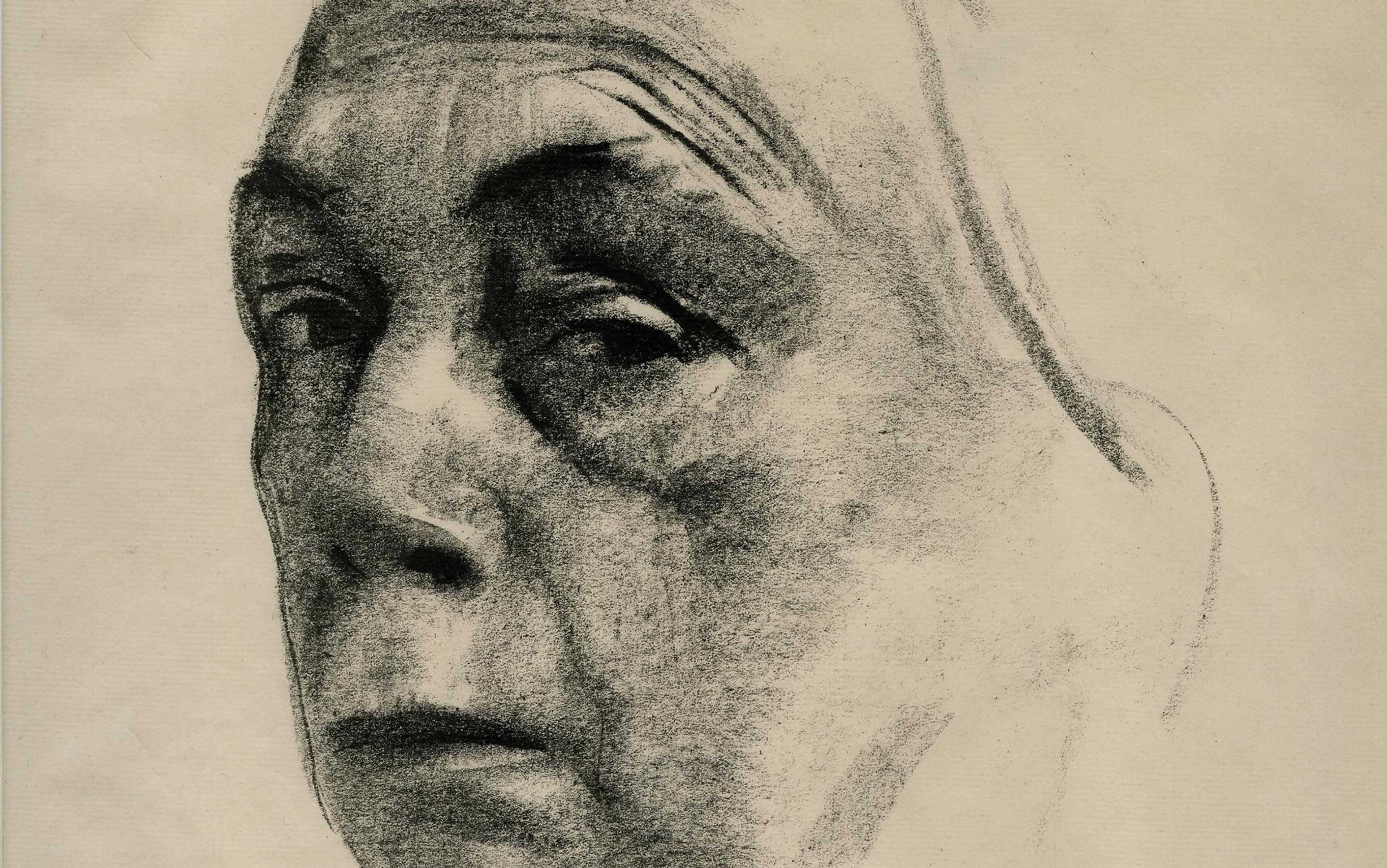

But at some point, elaboration becomes critical. Although preserving the deceased parent’s loving image in the child’s mind is admirable, simply attributing the suicide to depression, a fatal psychological or psychiatric flaw, or the person’s inability to manage stress, runs the risk of the child worrying that such problems will ultimately befall them too. The mirror offers each of us unavoidable glimpses of our parents slowly creeping into our own self-image; if we’re lucky, this means sometimes grimacing at the sight of an all-too-familiar receding hairline, the knowing insincerity of a smile, or maybe some deepening troughs of wrinkles. I think we all use brutal yardsticks to compare ourselves to our parents when they were our age. But for one whose mother or father has taken their own life, every year closer to the age of the parent’s last act can bring more self-reckoning with demons. ‘That’s it then, I guess I’m next,’ said a 16-year-old boy after his father’s suicide. ‘I feel tainted,’ said another, ‘as if I have inherited bad blood.’

It’s not an altogether irrational thought, either. Tragic examples of suicide running in families abound. Researchers in the 1940s wrote of a Spanish family in which the male descendants across five successive generations each killed themselves at the age of 45. And in 2009, 46 years after his mother, the poet Sylvia Plath, stuck her head in the oven after sealing the windows and doors to keep the gas from seeping into the children’s rooms, her son Nicholas Hughes, a fisheries biologist, hanged himself in Alaska.

Given the tendency for traumatised human beings to fall prey to their own self-fulfilling prophecies, experts say that it’s vital to unpack readymade explanations of genetic susceptibility with more nuanced language so that older children and teens aren’t left to their own fatalistic reasoning. Suicide, in fact, isn’t inevitable – there’s no ‘suicide gene’. The hereditability of mental illness isn’t so straightforward. And help is out there for those who seek it.

Maddy, for her part, wrestled alone with the many unknowns surrounding her father’s suicide. She also had to deal with what it meant for her, as a wife, as a mother, as a human being. She has an 11-year-old daughter now. ‘That’s what would stop me,’ she said. ‘I could never do that to her.’ (For women, in fact, having children has long been a well-known protective buffer against suicide, but more recent findings indicate that this applies only to mothers whose kids still live at home with them.)

Some of the so-called sleeper effects of parental suicide might not emerge until the child is on the verge of becoming a parent in their own right. ‘For adult children of suicide,’ writes Cain, ‘the most salient precipitate in their relationship with their offspring is the fear-laden expectation that their youngsters will also commit suicide … especially if a particular child [is] perceived as resembling the suicided grandparent in some significant respect – looks, temperament, talents, or interests.’ Because many such adult children of suicides keep the information assiduously hidden as a family secret, the third generation might be completely unaware of why their parent treats them the way they do.

Maddy knew the starkest of details from that terrible afternoon in her mother’s kitchen all those years ago. But that was it. Her parents had split up. He was down on his luck. She’d asked a man who could barely afford a shave to buy her a pony. ‘Because that,’ I reminded her, ‘is simply what 11-year-olds do.’

‘I never did feel any anger toward him,’ she said. ‘I’ve always had a sort of – oh god, maybe I’ve always been a sort of morose child myself, I don’t know – but I’ve always had an understanding. I felt sorry for him. Just … sad.’

The very capacity for empathy is severely constricted when in the throes of self-destructive thought

Still, Maddy longed for that lost connection with her dad. In her 30s, uncertainty gnawing, she took a bold leap by reaching out to the coroner’s office in Watford, the town near London in which her father had ended his life. ‘I remembered that somebody had mentioned there’d been a note,’ she said. ‘Whether my mother had intercepted it and not let us have it or not, I don’t know.’

The coroner still had a copy of her father’s suicide note, all those years later.

His letter arrived much later than it was meant to, but Maddy and her siblings are lucky in at least now knowing their dad’s final thoughts. The fact that only about 30 per cent of those who take their own lives leave a note, an astonishingly low figure given the impact on those left behind, is revealing in itself of the altered state of consciousness of the suicidal mind. In my book on the subject, Suicidal: Why We Kill Ourselves (2018), I show how the very capacity for empathy is often severely constricted when one is in the throes of self-destructive thought.

But that wasn’t the case for George Reid. Maddy shared her dad’s letter with me. Addressed to her, her brother Philip, and their sister Nicky, it spoke of existential despair, of his love for his children, of how he knew that this would undo them… and of music. On ponies, not a word:

I know this will be painful and bewildering but, for obvious reasons, I will not be there to comfort you … It has taken long and careful thought before I decided that the spark which enables one to carry on in the face of what seems an almost meaningless existence, coupled with constant financial problems, was not strong enough to see me through. Please take solace from the knowledge that I loved, and love, you all as much as anyone could, and I know that you will think of me often – I hope with tenderness – chiefly because we all love music and I hope that there will be many times when a tune will remind you of me.