Listen to this essay

18 minute listen

‘It’s natural,’ says the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ‘to think that time can be represented by a line.’ We imagine the past stretching in a line behind us, the future stretching in an unseen line ahead. We ride an ever-moving arrow – the present. However, this picture of time is not natural. Its roots stretch only to the 18th century, yet this notion has now entrenched itself so deeply in Western thought that it’s difficult to imagine time as anything else. And this new representation of time has affected all kinds of things, from our understanding of history to time travel.

Let’s journey back to ancient Greece. Amid rolls of papyrus and purplish figs, philosophers like Plato looked up into the night. His creation myth, Timaeus, connected time with the movements of celestial bodies. The god ‘brought into being’ the sun, moon and other stars, for the ‘begetting of time’. They trace circles in the sky, creating days, months, years. The ‘wanderings’ of other, ‘bewilderingly numerous’ celestial bodies also make time. When all their wanderings are ‘completed together’, they achieve ‘consummation’ in a ‘perfect year’. At the end of this ‘Great Year’, all the heavenly bodies will have completed their cycles, returning to where they started. Taking millennia, this will complete one cycle of the universe. As ancient Greek philosophy spread through Europe, these ideas of time spread too. For instance, Greek and Roman Stoics connected time with their doctrine of ‘Eternal Recurrence’: the universe undergoes infinite cycles, ending and restarting in fire.

Such views of time are cyclical: time comprises a repeating cycle, as events occur, pass, and occur again. They echo processes in nature. Day and night. Summer to winter. As the historian Stephen Jay Gould explains in Time’s Arrow, Time’s Cycle (1987), within the West, cyclical conceptions dominated ancient thought. It’s even hinted at in the Bible. For example, Ecclesiastes proclaims: ‘What has been will be again … there is nothing new under the sun.’ Yet, Gould writes, the Bible also contains a linear conception of time: time comprises a one-way sequence of unrepeatable events. Take Biblical history: ‘God creates the earth once, instructs Noah to ride out a unique flood in a singular ark.’ Gould describes this linear understanding of history as an ‘important and distinctive’ contribution of Jewish thought. Biblical history helped power linear ideas of time.

Cyclical and linear conceptions of time thrived side by side for centuries, sometimes blurring into one another. After all, we live through natural, cyclical seasons and unrepeatable events – birth, first marriage, death. Importantly, medievals and early moderns didn’t literally see cyclical time as a circle, or linear time as a line. Yet in the 19th-century world of frock coats, petticoats and suet puddings, change was afoot. Gradually, the linear model of time gained ground, and thinkers literally began drawing time as a line. To explain how, I point to four key developments.

First: chronography, the art of representing historical events. Historians have always struggled with how to best display events on a page, and since ancient times a popular solution lay in ‘time tables’: grids displaying dates.

From the 1856 edition of Blair’s Chronology. Public domain. Courtesy the Internet Archive

A crucial innovation lay in the invention of ‘timelines’. As Daniel Rosenberg and Anthony Grafton detail in their coffee-table gorgeous Cartographies of Time (2010), the ‘modern form’ of the timeline, ‘with a single axis and a regular, measured distribution of dates’, came into existence around the mid-18th century. In 1765, the scientist-philosopher Joseph Priestley, best known for co-discovering oxygen, invented what was arguably the world’s first modern timeline.

From A Chart of Biography (1765) by Joseph Priestley. Courtesy the National Endowmment for the Humanities

On his A Chart of Biography (1765), time flows from left to right, from 1200 BCE to (what was then) the present. More than 2,000 miniature lines painstakingly plot the durations of people’s lives, including the likes of Cicero, Queen Elizabeth I, and Isaac Newton. Because his method of representing time using lines was so novel, Priestley felt moved to justify it:

THAT there must be a peculiar advantage in a chart constructed in this manner I shall endeavour to show …

TIME … admits of a natural and easy representation in our minds by the idea of a measurable space, and particularly that of a line; which, like time, may be extended in length, without giving any idea of breadth or thickness. And thus a longer or a shorter space of time may be most commodiously and advantageously represented by a longer or a shorter line.

Rosenberg and Grafton describe A Chart of Biography as ‘path-breaking’, a ‘watershed’. ‘Within very few years, variations on Priestley’s charts began to appear just about everywhere … and, over the course of the 19th century, envisioning history in the form of a timeline became second nature.’ Priestley’s influence was widespread. For example, William Playfair, the inventor of line graphs and bar charts, singled out Priestley’s timeline as a predecessor of his own work. Rosenberg and Grafton explain that, over the next 50 years, Playfair’s line graph, which used one axis for time, and another for economic measures such as exports, ‘became one of the most recognisable chronographic forms’. By the time of Charles Dickens, timelines were common across books, posters, newspapers.

Chronophotography portrays a temporal process, such as a horse’s gallop, spread out across the page

The second key development concerns evolution. During the early 19th century, scientists created linear and cyclical models of evolutionary processes. For example, the geologist Charles Lyell hypothesised that the evolution of species might track repeatable patterns upon Earth. This led to his memorable claim that, following a ‘cycle of climate’, the ‘pterodactyle might flit again through the air.’ However, with the work of Charles Darwin, cyclical models faded. His On the Origin of Species (1859) conceives of evolution in linear terms. It literally includes diagrams depicting species’ evolution over time using splaying, branching lines. These diagrams assume a linear model of time: time runs in a linear, vertical fashion from the past at the bottom of the page to the present at the top. Gould describes Darwinian evolution as a linear ‘arrow’ in the ‘fullest sense’: ‘a quirky sequence of intricate, unique, unrepeatable events’.

The evolution of species through linear time, from On the Origin of Species (1859) by Charles Darwin. Courtesy NYPL

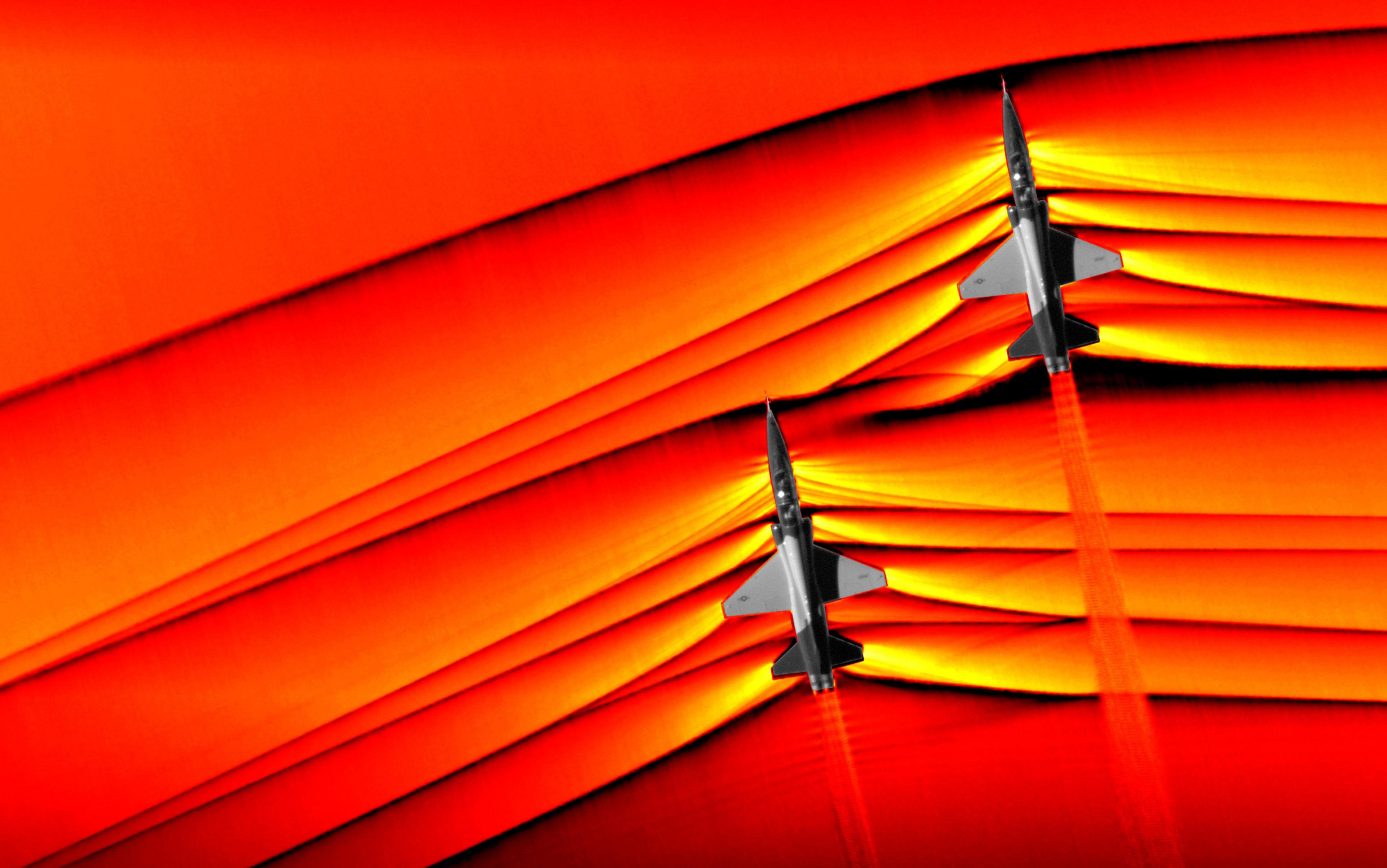

The third key development emerged in the 1870s: chronophotography. This new art form captured motion through successive images. Chronophotography seems to spatialise time by portraying a temporal process, such as a horse’s gallop, spread out across the page. In his landmark book Le Mouvement (1894), the photographer Étienne-Jules Marey opens with a statement that could be drawn directly from Priestley: ‘Time … can be represented in a graphic form by straight lines of various lengths.’

Arab Horse at a Gallop (1887) by Étienne-Jules Marey. Public domain, courtesy of Wikipedia Commons

The last development stemmed from mathematics: theories of the fourth dimension. Humans perceive three spatial dimensions: length, width, and depth. But mathematicians have long theorised there were more. In the 1880s, the mathematician Charles Hinton popularised these ideas, and went further. He didn’t just argue that space has a fourth dimension, he identified time with that dimension. Hinton argued that, because of the limitations of human consciousness, we perceive four-dimensional objects as changing three-dimensional objects. Yet reality is really an unchanging, four-dimensional space. What we perceive as time is misperceived space. The world is a ‘stupendous whole, wherein all that has ever come into being or will come co-exists’. Hinton doesn’t describe time as a line but, implicitly, describing time as a dimension of space means that, if time were taken by itself, it would be a line. Hinton’s work was speedily absorbed into the 19th-century air, and soon other 1880s thinkers were identifying the fourth dimension of space with time.

Four-dimensional cubes by Charles Hinton, 1880s. Courtesy the Public Domain Review

By the late 19th century, representing time as a line was not just widespread – it was natural. Like today, it would have been hard to imagine how else we could represent time. And this affected how people understood the world.

Within history, conceiving of time as a line helped to fuel the notion that humanity is making progress. Joseph Priestley, our timeline inventor, is partly responsible for this. The man once listed inventions that have made people happier, including flour mills, linen, clocks, and window glass. His Chart of Biography evidenced this positive take on human progress. It places figures into groups, such as ‘Artists & Poets’, ‘Mathematicians & Physicians’, ‘Divines and Metaphysicians’. If you look back to his Chart, you’ll see that, as time goes on, increasing numbers of these figures appear. This confirmed Priestley’s belief that humanity is improving.

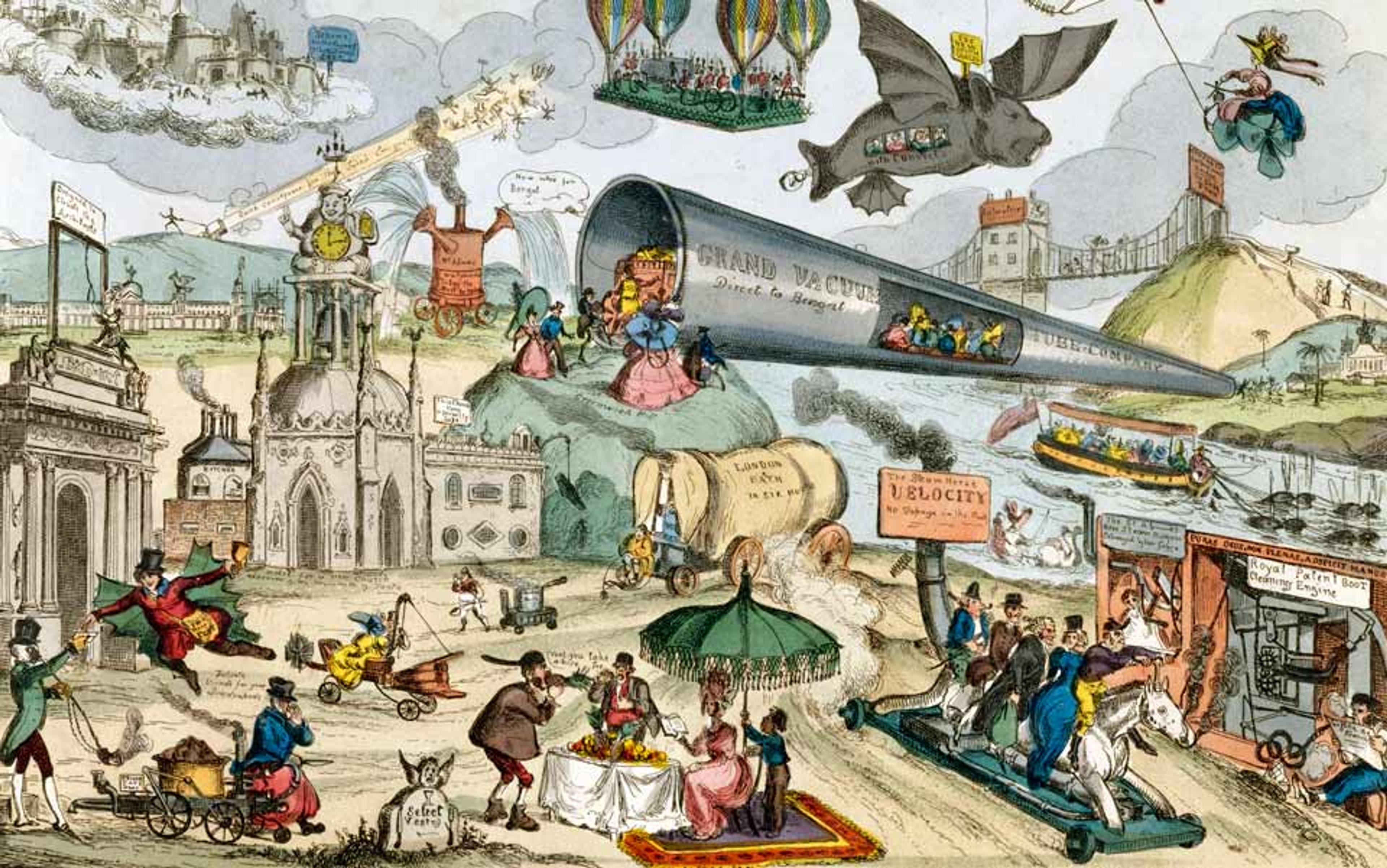

For Victorians, belief in progress only grew, impelled by rapid scientific and technological development. Victorians saw the invention of railway systems, light bulbs, telegraphs, typewriters, fridges, telephones. The historian Thomas Macaulay claimed: ‘The history of England is emphatically the history of progress.’ Such narratives received further support via the ideas of Darwinian evolution.

Darwinian evolution was portrayed not as a many-branched tree, but as an arrow

Darwin’s evolutionary diagrams resemble trees with forking branches. As the historian of science Peter Bowler explains, this rightly implies that ‘evolution has no main line and hence no particular goal’: ‘The human race is not the inevitable end-product of animal evolution, but an unusual species formed by a unique combination of circumstances forced upon its ancestors.’ Nonetheless, Darwin made sure that On the Origin of Species could be interpreted as progressivist. For example, the book bluntly states that life forms ‘tend to progress towards perfection’. Victorians took this on board, cheerfully incorporating evolution into their broader story of progress. Darwinian evolution was portrayed not as a many-branched tree, but as an arrow: over time, species evolved in a line from less perfect to more perfect.

Within philosophy, conceiving of time as a line led to thinkers debating the reality of the past and future. Picture a line: all its parts, the fractions of ink that make it up, exist. When we picture time as a line, this leads us to think that all its parts exist too. In the 1870s, the German philosopher Hermann Lotze became anxious about this. ‘We speak of Time as a line, but,’ he writes, ‘the conception of a line involves that of a reality belonging equally to all its elements. Time however does not correspond to this.’ For Lotze, if time were a line, it would only ‘possess one real point’: ‘the present’.

Early 20th-century philosophy saw major debates emerge over the reality of the past and future. In my view, these debates were triggered by the new idea that time is a line. On one side of these stood the likes of Lotze, who argued that only the present exists. Henri Bergson also argued for the unreality of the future, attacking the linear conception of time. His very first book, Time and Free Will (1889), argues vehemently that ‘time is not a line’ (my emphasis). Amusingly, in the English translation of this book, the index entry for ‘Line’ provides page references to ‘time not a’. Later, Bergson’s Creative Evolution (1907) attacks the new arts of chronophotography and cinematography, for failing to capture the true nature of time. The Frenchman writes: ‘Of the gallop of a horse our eye perceives chiefly a characteristic, essential … form.’ In contrast, ‘instantaneous photography’ spatially ‘spreads out’ the horse’s gallop, portraying mere ‘quantitative variations’. The naked eye captures the form of a horse’s gallop in a way that photography cannot.

On the other side of this debate stood the likes of the British philosopher Victoria Welby, who drew on chronophotography and the fourth dimension to argue that time is literally space. The past is as real as a piece of land we’ve just journeyed through, the future as real as the country waiting ‘below a given horizon’. Similarly, Bertrand Russell argued: ‘Past and future must be acknowledged to be as real as the present.’ Evoking new art forms, Russell proudly describes his view as ‘cinematographic’. His peer Samuel Alexander also argued for the reality of past, present and future, and offers a similarly cinematographic theory. If we could properly see the world, Alexander argues, we would see that past events do not ‘vanish’. They have merely ‘moved back upon the film’. Our present is merely further forwards on the reel of film that is reality.

Of course, the best development produced by conceiving of time as a line was time travel. People had imagined visiting the past or future in one way or another for centuries – by dreams, or visions – but H G Wells gave it a whole new, scientific spin. His novel The Time Machine (1895) drew directly on Hinton’s ‘fourth dimension’ to explain how we can travel in time. As his fictional time-traveller puts it:

There are really four dimensions, three which we call the three planes of Space, and a fourth, Time. There is, however, a tendency to draw an unreal distinction between the former three dimensions and the latter, because it happens that our consciousness moves intermittently in one direction along the latter from the beginning to the end of our lives …

Really this is what is meant by the Fourth Dimension … It is only another way of looking at Time.

Conceiving of time as the fourth dimension of space enables time travel

Decades later, Wells described the core of his novel as ‘the idea that Time is a fourth dimension and that the normal present is a three-dimensional section of a four-dimensional universe.’ This is pure Hinton, writ large.

The Time Machine also happily conceives of time as a line:

Scientific people … know very well that Time is only a kind of Space. Here is a popular scientific diagram, a weather record. This line I trace with my finger shows the movement of the barometer. Yesterday it was so high, yesterday night it fell … Surely the mercury did not trace this line in any of the dimensions of space generally recognised? But certainly it traced such a line, and that line, therefore, we must conclude, was along the Time-Dimension.

The barometer’s line was traced through time, rendering it another dimension of space. And, of course, for Wells’s story, conceiving of time as the fourth dimension of space enables time travel. One of his characters argues: ‘admit that time is a spatial dimension … it becomes possible to travel about in time’. After Wells, time-travel stories exploded. One critic dubbed Wells the ‘literary pioneer of time travel’.

Today, conceiving of time as a line remains widespread. Timelines are everywhere: in the history of evolution, the history of video games, and the history of chocolate. There’s even a timeline of timelines. And the effects of this line of thought (pun intended) are still with us. Philosophers continue to debate the reality of past and future: just check out this bumper encyclopaedia article on ‘Presentism’, ‘the view that only present things exist’. Time-travel stories run rife. Back to the Future. Groundhog Day. The Time Traveler’s Wife. Historians have largely dropped Victorian faith in the progress of humanity, yet progress stories about particular areas remain. For example, take this timeline: it straightforwardly depicts technological progress over time. All these ideas are powered by the notion that time is a line. Were we to reshape our idea of time, perhaps these other ideas would also find themselves bent into new forms.