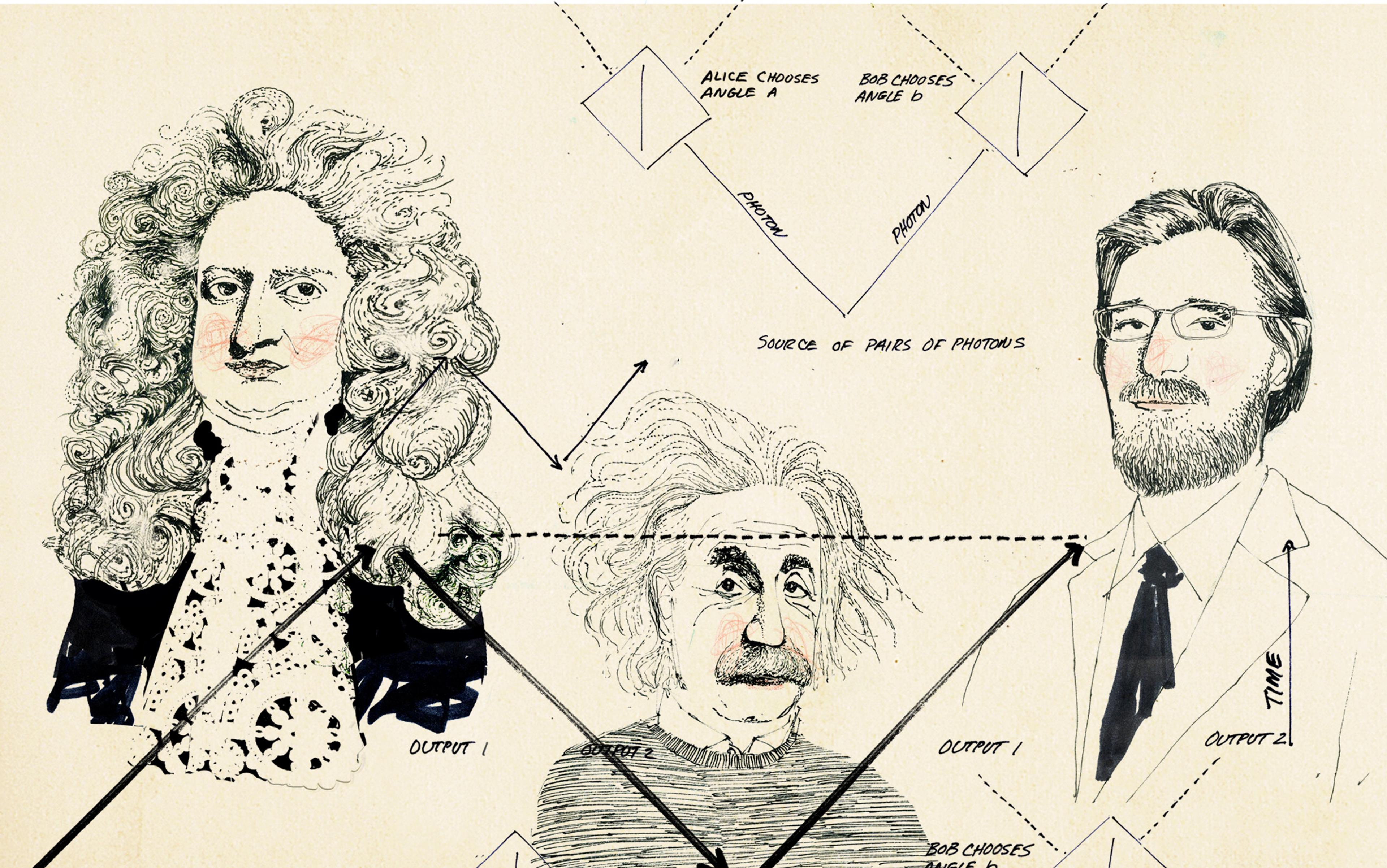

On the evening of 6 April 1922, during a lecture in Paris, the philosopher Henri Bergson and the physicist Albert Einstein clashed over the nature of time in one of the great intellectual debates of the 20th century. Einstein, who was then 43 years old, had been brought from Berlin to speak at the Société française de philosophie about his theory of relativity, which had captivated and shocked the world. For the German physicist, the time measured by clocks was no longer absolute: his work showed that simultaneous events were simultaneous in only one frame of reference. As a result, he had, according to one New York Times editorial, ‘destroyed space and time’ – and become an international celebrity. He was hounded by photographers from the moment he arrived in Paris. The lecture hall was packed that April evening.

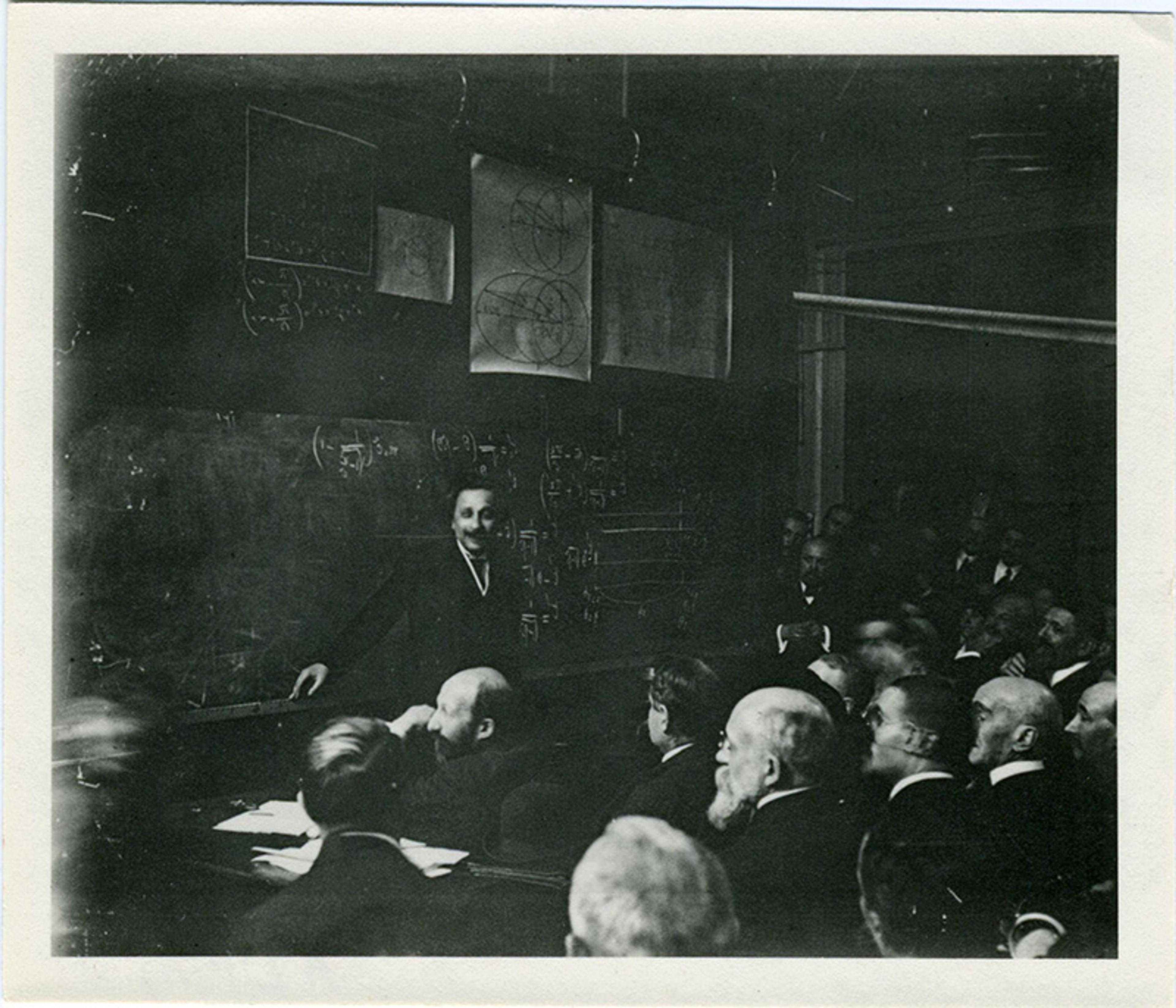

Albert Einstein at the College de France, with Henri Bergson in the audience (second along from white-bearded man). Paris, 1922. Courtesy and © Leo Baeck Institute, New York

Sitting among the gathered crowd was another celebrity. Bergson, then aged 62, was equally renowned internationally, particularly for his bestselling book Creative Evolution (1907), in which he had popularised his philosophy based on a concept of time and consciousness that he called ‘la durée’ (duration). Bergson accepted Einstein’s theory in the realm of physics, but he could not accept that all our judgments about time could be reduced to judgments about events measured by clocks. Time is something we subjectively experience. We intuitively sense it passing. This is ‘duration’.

Their debate began almost by accident. The meeting in April had been convened to bring together physicists and philosophers to discuss relativity theory, but Bergson came intending only to listen. When the discussion flagged, however, he was pressed to intervene. Reluctantly, he rose and presented a few ideas from his forthcoming book, Duration and Simultaneity (1922). As Jimena Canales documented in her book The Physicist and the Philosopher (2015), what Bergson said in the following half an hour would set in motion a debate that reverberated through the 20th century and down into the 21st. It would crystallise controversies still alive today, about the nature of time, the authority of physics versus philosophy, and the relationship between science and human experience.

Bergson began by declaring his admiration for Einstein’s work – he had no objection to most of the physicist’s ideas. Rather, Bergson took issue with the philosophical significance of Einstein’s temporal concepts, and he pressed the physicist on the importance of the lived experience of time, and the ways that this experience had been overlooked in relativity theory.

Though Einstein was forced to speak in French, a language of which he had a poor command, he took only a minute to respond. He summarised his understanding of what Bergson had said and then shrugged away the philosopher’s ideas as irrelevant to physics. Einstein believed that science was the authority on objective time, and philosophy had no prerogative to weigh in. To end his rebuttal, he declared: ‘[T]here is no time of the philosopher; there is only a psychological time different from the time of the physicist.’

But despite what many have come to believe about the debate that began that night, Einstein was wrong. There is a third kind of a time: a time of the philosopher.

Henri Bergson in 1908. Courtesy the University of Salamanca, Spain. CC BY-NC-ND

When Duration and Simultaneity was published later that year, Bergson’s debate with Einstein became more public and widespread, drawing in many other physicists and philosophers. But as it spread, cracks began to appear in the philosopher’s claims. The argument showed that Bergson had misunderstood an important technical aspect of Einstein’s theory of special relativity, particularly concerning time dilation (the difference in elapsed time, as measured by two clocks, due to their relative velocities). Due to this failing, many came to believe not only that Einstein won the debate, but that the philosophy of duration had no relevance to the world of physics. Bergson began to appear out of touch with the cutting edge of science. As the philosopher Thomas L Hanna wrote in 1962:

Einstein’s theories gradually received increasingly dramatic verification, while Bergson’s theories wilted on the vine. The best explanation for Bergson’s impressive failure … [is that] he was not sufficiently conversant with the outlook and problems of mathematics and physics.

Even the Nobel laureate Ilya Prigogine and the philosopher Isabelle Stengers, who were sympathetic to Bergson’s philosophy in their groundbreaking book Order Out of Chaos (published first in French in 1978), wrote that he had ‘obviously misunderstood Einstein’s theory of relativity’.

But close examination of Bergson’s work does not bear out these lopsided judgments. He was out of touch neither with science nor mathematics. In fact, he was adept at mathematics – he had won a prestigious mathematics prize, and his first published work was in a mathematics journal. And though he was wrong about one technical aspect of relativity theory, he was right about something more fundamental: time is not just what clocks measure. It must be understood in other ways that draw directly on our experience of duration.

Bergson insisted that duration proper cannot be measured

To understand the French philosopher’s view of time, we need to return to the 1880s, when he was working on his doctoral thesis. This work would be published as his first book in 1889 – known in English as Time and Free Will: An Essay on the Immediate Data of Consciousness – when he was 30. The book’s key contribution is the idea that time is not space. We usually imagine time as analogous with space. We imagine it, for example, laid out on a line (like a timeline of events) or a circle (like a sundial ring or a clock face). And when we think of time as the seconds on a clock, we spatialise it as an ordered series of discrete, homogeneous and identical units. This is clock time. But in our daily lives we don’t experience time as a succession of identical units. An hour in the dentist’s chair is very different from an hour over a glass of wine with friends. This is lived time. Lived time is flow and constant change. It is ‘becoming’ rather than ‘being’. When we treat time as a series of uniform, unchanging units, like points on a line or seconds on a clock, we lose the sense of change and growth that defines real life; we lose the irreversible flow of becoming, which Bergson called ‘duration’.

Think of a melody. Each note has its own distinct individuality while blending with the other notes and silences that come before and after. As we listen, past notes linger in the present ones, and (especially if we’ve heard the song before) future notes may already seem to sound in the ones we’re hearing now. Music is not just a series of discrete notes. We experience it as something inherently durational.

Bergson insisted that duration proper cannot be measured. To measure something – such as volume, length, pressure, weight, speed or temperature – we need to stipulate the unit of measurement in terms of a standard. For example, the standard metre was once stipulated to be the length of a particular 100-centimetre-long platinum bar kept in Paris. It is now defined by an atomic clock measuring the length of a path of light travelling in a vacuum over an extremely short time interval. In both cases, the standard metre is a measurement of length that itself has a length. The standard unit exemplifies the property it measures.

In Time and Free Will, Bergson argued that this procedure would not work for duration. For duration to be measured by a clock, the clock itself must have duration. It must exemplify the property it is supposed to measure. To examine the measurements involved in clock time, Bergson considers an oscillating pendulum, moving back and forth. At each moment, the pendulum occupies a different position in space, like the points on a line or the moving hands on a clockface. In the case of a clock, the current state – the current time – is what we call ‘now’. Each successive ‘now’ of the clock contains nothing of the past because each moment, each unit, is separate and distinct. But this is not how we experience time. Instead, we hold these separate moments together in our memory. We unify them. A physical clock measures a succession of moments, but only experiencing duration allows us to recognise these seemingly separate moments as a succession. Clocks don’t measure time; we do. This is why Bergson believed that clock time presupposes lived time.

Bergson appreciated that we need the exactitude of clock time for natural science. For example, to measure the path that an object in motion follows in space over a specific time interval, we need to be able measure time precisely. What he objected to was the surreptitious substitution of clock time for duration in our metaphysics of time. His crucial point in Time and Free Will was that measurement presupposes duration, but duration ultimately eludes measurement.

Einstein had a different understanding of time. In his paper ‘On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies’ (1905), he claimed to have defined time entirely in objective terms. Using ‘certain imaginary physical experiments’ as objective procedures or tests, he gave definitions for the concepts of ‘time’, ‘synchronous’, and ‘simultaneous’. He writes:

We have to take into account that all our judgments in which time plays a part are always judgments of simultaneous events. If, for instance, I say: ‘That train arrives here at 7 o’clock,’ I mean something like this: ‘The pointing of the small hand of my watch to 7 and the arrival of the train are simultaneous events.’

Definitions based on such ‘imaginary physical experiments’ would go on to support Einstein’s ideas about relativity. For Einstein, the ‘time’ of an event is ‘that which is given simultaneously with the event by a stationary clock located at the place of the event, this clock being synchronous, and indeed synchronous for all time determinations, with a specified stationary clock’. This definition uses simultaneity between a local event and a local clock to define the time of the event. But what counts as so-called local simultaneity depends on the direct experience of someone perceiving both the event and the clock together in one subjective ‘now’. As Bergson argued in the 1922 debate, local simultaneity is always something that is perceived by conscious beings. Clocks don’t read themselves. Moreover, local simultaneity is relative to the perceiver: what is locally simultaneous for an intelligent microbe with a microbe-sized clock, to use Bergson’s example, differs from what is locally simultaneous for a human perceiver with a watch. This means that Einstein’s definitions are not completely objective – they rely on the perceiver’s subjective experience of time for their meaningfulness, not just on objective procedures or tests. Only a conscious observer can establish simultaneity between an event and a clock. To read a clock, you already have to know what time is, and that’s something no clock can tell you.

Einstein’s real mistake was not to omit duration from special relativity theory

Bergson accepted that, for physicists to measure exact moments (ie, to precisely identify the time of an event), they need to simplify the continuous experience of time and abstract away from the concept of duration. He did not object to these kinds of abstractions. What he did object to was surreptitiously substituting the instant (an infinitesimal temporal interval whose passage is instantaneous) for duration in the metaphysics of time. He was objecting to the way Einstein had forgotten that the concept of the instant is meaningful only as an abstract simplification of our concrete experience of duration. Bergson wanted Einstein to see that the intuitive or experiential concept of simultaneity, which is based on our lived experience of duration, lay buried in the definition supporting the theory of relativity. He was calling attention to an amnesia of experience in mathematical physics.

These objections had little impact on Einstein, either in 1922 or the years after. For the physicist, the final test was simply whether his theory worked. Understanding the lived experience of time would not have helped him in his theory, which is why he deemed duration irrelevant – and there is nothing wrong with that. His real mistake was not to omit duration from special relativity theory. Rather, it was his view that physical time, defined through the measurements of clocks, was more fundamental than lived time.

At this point you might object: isn’t duration just something happening inside our heads? Isn’t our experience of time passing a cognitive illusion arising from measurable activity in our brains? For example, whether two lights are judged as simultaneous or sequential, or as a single moving light, depends not just on the amount of time between them but also on how they relate to the brain activity of the perceiver. So why can’t we say that our experience of duration is just a result of our brains smoothing over fine, granular details so that time seems to flow?

This takes us to Einstein’s final rebuttal from the evening in 1922: ‘[T]here is no time of the philosopher; there is only a psychological time different from the time of the physicist.’ What he meant by ‘psychological time’ was that our internal experience of time could be aligned with external clock time, and that this could allow experts to meaningfully describe our perceptions. This idea of a psychological time, however, does not come to grips with the more fundamental philosophical issue Bergson raised: duration is not the same as psychological time.

Measuring clock time, whether in physics or psychology, is always downstream from the lived experience of duration

When neuroscientists research time perception, they apply clock time to the neural correlates, behavioural indications and verbal reports of lived time. This allows them to learn valuable information about how human brains parse time. It also allows them to produce third-person descriptions that relate consciousness to the brain as a physical system. But these third-person descriptions do not suffice to explain the first-person experience of duration. There remains an unexplained gap between brains and consciousness.

Duration helps us make sense of this gap. To produce their descriptions, neuroscientists rely on their own first-person experience of time. They do this whenever they read clocks and measure time intervals in the laboratory; whenever they apply clock time to observable biological and behavioural processes; and whenever they infer back to aspects of duration that they can extract and stabilise as objects of thought and attention. In fact, all their work takes place inside lived time. Yet, they can never step outside of this experience and exhaustively explain it. Duration is conveniently ignored. For these reasons, it’s wrong to think that Bergson’s idea of duration can be assimilated into the idea of psychological time in the sense that Einstein meant. Measuring clock time, whether in physics or psychology, is always downstream from the lived experience of duration.

Einstein did not understand this point. Bergson thought that a careful philosophical analysis of relativity theory would show that the intelligibility of measurable clock time was inextricable from lived time – this was the task he set for himself in Duration and Simultaneity. Unfortunately, his message got lost in the debate because of a mistake made in his treatment of special relativity. This mistake is the reason why so many believed that Einstein ‘won’ their debate. It is part of the reason why Bergson’s theories ‘wilted on the vine’ throughout the 20th century.

The crux of Bergson’s misunderstanding lay in his struggle to reconcile his own philosophical views with the empirical realities of Einstein’s theory. In Time and Free Will, Bergson had argued that there is one universal time of duration in which all consciousness participates. Confronted by Einstein’s ideas, he sought to reconcile his belief in a singular and universal duration with the plural times of special relativity theory. The way he did this was to argue that the plurality of times should be regarded as strictly mathematical rather than physically real.

Bergson focused on the phenomenon of time dilation. Time dilation is the difference in elapsed time as measured by two clocks due to their relative velocities. The faster clock is the one at rest and the slower one is in motion. But there is no absolute state of rest in relativity theory. Any observer can regard themselves as being at rest while regarding others (ie, other reference frames) as being in motion. That is why time dilation always affects the clock of the ‘other’ observer regarded as being in motion relative to the one taken as being at rest.

Bergson reasoned that, since there is no absolute frame of reference in special relativity theory (and the reference frames do not undergo acceleration), the observers’ situations are symmetrical and interchangeable, and therefore the plurality of times should be regarded as just mathematical, and not physically real. And if the many times were regarded as strictly mathematical, then they could be made consistent with the one real time of duration. This is where Bergson went astray.

Time dilation exists only relative to another reference frame and can be seen only from the outside

He focused on the so-called twin paradox in which one twin remains on Earth while his brother travels to outer space in a rocket ship at near the speed of light and then returns to Earth at the same speed. According to special relativity theory, when they compare their clocks (which were identically constructed and synchronised at the start of the journey), more time has elapsed for the twin who stayed on Earth, and he appears to have aged more than his brother. Bergson rejected this idea. He argued that, as long as the twins’ situations were strictly identical and there was no acceleration, the returning clock would show no slowing on its arrival back on Earth. In his view, the clock times were not physically real. They were just mathematical abstractions. But Bergson was proven wrong. Time dilation, predicted by special relativity, was experimentally confirmed as a physical phenomenon in 1971.

Bergson had argued for two things, one incorrect and the other correct. It was a mistake to claim that time dilation is not physically real, but he was right in claiming that no one experiences the time dilation of their own reference frame. Time dilation exists only relative to another reference frame and can be seen only from the outside. This means that time dilation is not a measure of anyone’s time from within their own reference frame. A reference frame is an abstraction, not a concrete domain of experience, and it can be specified only relative to another reference frame. And so, Bergson was right to argue that each twin experiences only his own time. This point, however, like many others, was ignored or overlooked by Einstein.

Bergson insisted that the travelling twin would not feel time slowing down. To notice time dilation, he would have to stand outside his reference frame and compare clock readings with the twin who remained on Earth. Without this comparison, the dilation would not be noticed because he would not have felt time slowing down. Some might argue that Bergson overlooked the dependence of experience on brain activity, which also slows down in the travelling twin, meaning that the traveller’s stream of consciousness would elapse more slowly relative to that of his brother. Nevertheless, this slowing would not be noticed by the traveller. The slower rate of passage exists, or is what it is, only relative to the other reference frame on Earth. So it makes no sense to say that the travelling twin experiences a different time from that of his twin. They both experience duration, though their individual experiences of duration are particular to them. In Bergson’s words, a twin who experiences a different time is a ‘phantom’, a ‘mental view’ or an ‘image’, appearing to the perspective of the twin on Earth.

Bergson thought that if a measurement of time lost its connection to duration, it wasn’t really a measurement of time. And this is what he believed had happened to the different times of special relativity. For Bergson, there was no duration in Einstein’s conception of time dilation. Time dilation shows up only as a difference between clock readings, or a difference between the worldlines (the unique paths of objects through spacetime) computed by a physicist. But no one experiences a different rate of passage. Such difference can’t be experienced directly because as soon as you mentally transpose yourself to the reference frame where time dilation is happening, time dilation disappears and reappears in your original reference frame. Here, Bergson was correct.

In the century since 1922, the conceptual distance between the German physicist and the French philosopher seems to have shrunk. It turns out that there is a way to reconcile Bergson’s ideas with special relativity theory – though none of the parties to the debate seems to have noticed it. As the philosopher Steven Savitt has suggested, duration can be understood as the passage of local or ‘proper time’ – the time measured by a clock following along with an object’s worldline within a reference frame (eg, following a twin leaving Earth at the speed of light). In other words, proper time can be understood as measurable clock time based on the duration proper to an observer within a reference frame.

But this reconciliation implies that duration is many, not one, which is something Bergson wanted to avoid because he believed duration was singular and universal. According to this reconciliation, the passage of time is always given from some experienced perspective in the Universe and never from outside it. Duration is many because there is no upper bound on the number of possible perspectives and associated worldlines. Every person, every insect, every rock – every thing – has its own worldline. And each of these worldlines reflects a unique passage through time and possible experience of duration. Better still, each worldline represents the distillation of a unique durational flow, since a worldline is a mathematical abstraction, whereas passage (the experience of time passing) is concrete. The Universe is teeming with times and potential durational rhythms. This means that there is no temporal bird’s-eye view of the Universe that flies above and beholds all these times as one.

Measurable times and durational rhythms may differ, but the experience of time passing is ultimately immeasurable

Through these teeming times and durational rhythms, we can see how the so-called block-universe theory, which has been thought to follow from relativity theory, goes astray. According to this theory, the passage of time is an illusion because the past, present and future all constitute a single block in four-dimensional spacetime. But it is impossible to conceive of the contemporaneous reality of all the events in such a block universe without adopting a bird’s-eye (or God’s-eye) perspective external to the Universe and the passage of nature. Reconciling Bergson and Einstein shows us that there cannot be such a temporal bird’s-eye view of the Universe. There is no way of seeing outside and above the disparate paths through spacetime and the different rhythms of duration.

And yet, despite these proliferating times, there is a sense in which duration is also singular and universal, as Bergson thought. Measured time always presupposes the same ineliminable concrete fact of duration or temporal passage. Measurable times and durational rhythms may differ, but the experience of time passing is ultimately immeasurable and resists explanation in terms of anything else. As the mathematician and philosopher Alfred North Whitehead argued around the same time as Bergson, we can single out the characteristic of nature’s passage and describe its relation to other characteristics of nature but we cannot explain it by deriving it from something else – such as the temporal units of a clock. When we measure seconds, hours or other temporal intervals, we measure elapsed time, which depends on the experience of duration. But, as we know, duration cannot be fully understood by measuring these intervals.

Since clock time presupposes the experience of duration, to claim that duration and the ‘now’ are an illusion, as Einstein did, cuts out the ground on which science must stand. Investigating that ground and gaining cognitive insight into it are the remit of philosophy, which transcends science. There is a time of the physicist and a time of the psychologist. But there is also a time of the philosopher, which lies beneath both, and which Einstein failed to grasp.

The debate that began on the evening of 6 April 1922 and expanded through the 20th century represents a missed opportunity for moving our scientific worldview beyond its blind spot – its inability to see that lived experience is the permanent, necessary wellspring of science, including abstract theories in mathematical physics. In retrospect, we can see that the debate was an unfortunate misunderstanding. Bergson’s and Einstein’s ideas are more aligned than either realised during their lifetimes. By combining their insights, we gain an understanding of something fundamental. All things, us included, embody different durations as they move through the Universe. There is no one time. Through his attempts to show Einstein a hidden world of duration passing beneath special relativity, Bergson continues to remind us of something forgotten in our scientific worldview: experience is the ineliminable source of physics.

Parts of this essay were adapted from The Blind Spot: Why Science Cannot Ignore Human Experience (2024) by Adam Frank, Marcelo Gleiser and Evan Thompson.