Heini Hediger, a noted 20th-century Swiss biologist and zoo director, knew that animals ran away when they felt unsafe. But when he set about designing and building zoos himself, he realised he needed a more precise understanding of how animals behaved when put in proximity to one another. Hediger decided to investigate the flight response systematically, something that no one had done before.

Hediger found that the space around an animal could be partitioned into zones, nested within one another, and measurable down to a matter of centimetres. The outermost circle is what’s known as flight distance: if a lion is far enough away, a zebra will continue to graze warily, but any closer than that, the zebra will try to escape. Closer still is the defence distance: pass that line and the zebra attacks rather than fleeing. Finally, there’s the critical distance: if the predator is too close, there’s nothing to do but freeze, play dead and hope for the best. While different species of wild animals have different limits, Hediger discovered that they’re remarkably consistent within a species. He also offered a new definition of a tame animal, as one that no longer treats humans as a significant threat, and so reduces its flight distance for humans to zero. In other words, a tame animal was one to which you could get close enough to touch.

Like all animals, humans also protect themselves from potential threats by keeping them at a distance. Those of us beginning to see friends again after months of pandemic-induced social distancing can feel this at a visceral level, as we balance the desire for contact against a sense of risk. Once we evaluate something as a potential threat – even if that assessment is informed by public policy or expert prescription – there’s a powerful urge to maintain a buffer of space.

This buffer is a byproduct of our evolutionary history, which has equipped our brains with a way to acknowledge and track the importance of our immediate surroundings. That mechanism is known as peripersonal space, the region in and around a person’s body (peri comes from the Ancient Greek meaning ‘about’, ‘around’, ‘enclosing’ or ‘near’). Peripersonal space exists in various forms across the animal kingdom, from fish and fruit flies to wild horses and chimpanzees. The neuroscience behind it sheds fascinating light on how humans and other animals conceive of themselves and their boundaries. Where is the dividing line between you and the world? You might think that this is a clean-cut question with a simple answer – your skin is the boundary, with the self on one side and the rest of the world on the other. But peripersonal space shows that the division is messy and malleable, and the boundary is blurrier than you might think.

The peripersonal zone is a nexus where space, time and survival are tightly bound together. Maintaining a buffer of peripersonal space is important because it gives an animal time to react to a threat before it’s too late. A predator isn’t merely present at an objective distance, but feels either too close for comfort or far enough away. Peripersonal space, then, is space that has significance, and this significance depends on what matters to you, and on your state of mind. The story of peripersonal space is thus a story about the entanglement of space and meaning. It’s also the story of why ‘needing space’ during stressful times is more than just a metaphor, or how we can successfully navigate the crowded metro during rush hour, or how we can hammer a nail without hitting our thumb. And it is, deep down, a story of all the beautiful neural engineering that allows for self-protection in an ever-changing world.

Hediger’s concentric zones capture the logic of escalating threat: the closer something is, the fewer options you have. A snake across the field gives you time to think about what to do. A snake next to your foot requires immediate action. ‘By far the chief preoccupation of wild animals at liberty is finding safety,’ Hediger noted, in a rare poetic moment:

The be-all and end-all of its existence is flight. Hunger and love occupy only a secondary place, since the satisfaction of both physical and sexual wants can be postponed while flight from the approach of a dangerous enemy cannot.

There’s a close link, in other words, between physical and temporal immediacy when we respond to threats. Though many humans rarely encounter predators, we obey the same principles. You walk into a classroom packed with students and their bags; you automatically avoid the obstacles in your path. You traverse a small mountain path; the distance to the edge is always vivid in your mind. As you pass through a narrow turnstile, without thinking, you tilt your torso to avoid bumping the frame. Our life is full of these small adjustments to protect our bodies. Philosophers have paid a lot of attention to the role of pain in bodily protection. But pain is a last-ditch warning system: by the time you feel it, you’ve usually already gone wrong.

Keeping a buffer of space around you doesn’t require a conscious desire to avoid danger. Many of these small adjustments are performed automatically, and we barely notice when we do them – though sometimes we can consciously feel the proximity of others. Since the 1960s, social psychologists and anthropologists such as Edward T Hall have noted that we feel discomfort when other people get too close. When you’re seated alone on a long empty bench in a waiting room and a perfect stranger sits down beside you, his intrusion within your space is almost certain to make you feel uncomfortable. One way to interpret this effect is that your perceptual system anticipates this perfect stranger touching you, and you experience this social contact as being unwelcome – repulsive in a very literal sense.

Yet, for all the talk of boundaries and special margins, it was a long time before scientists realised that that the distinction between near and far in space is one that the brain also treats as especially important. The neuroscientist Giacomo Rizzolatti and his collaborators were the first to find evidence that peripersonal space was specially encoded by the brain. In a series of experiments on macaques, they found neurons that fired not only when a monkey was touched on the skin, but also when it saw a flash of light near its body. The sensitive region of the space was locked to the body itself; if a neuron fired in response to threats near the hand, the bubble of space it monitored would move as the hand moved.

The neuroscientist Michael Graziano provided further insight into the role of these neurons by stimulating them via tungsten microelectrodes inserted directly into the brains of macaques. Electrical current in these regions would cause the macaque to act as if it were under threat: flinching, twisting or raising its hand to ward off unseen dangers. Conversely, cooling the same neurons to prevent them from firing kept the monkey from responding to apparent threats.

Peripersonal space isn’t just a zone you use to protect yourself, but also from which to explore the world

The same mechanism has since been described in humans, and appears to be present from an early age. What is close to our body can soon be in contact with it, either because the nearby object moves or because you move. It’s almost as if it were already touching us. Hence, seeing or hearing objects close to us affects our tactile sensations. For instance, as discovered by the neuroscientist Andrea Serino and his team, hearing noises occurring near the body part, even in the dark, can disrupt where we feel touch. This is why Graziano qualifies peripersonal space as a ‘second skin’. It’s why, even if the person coughing is relatively far away, we’ll perceive her as being close because we feel that she can have an impact on us.

To provide further clues on the neuropsychology of peripersonal space, pioneers in the field such as Elisabetta Làdavas and Alessandro Farnè have investigated a curious phenomenon known as visuo-tactile extinction. After a right-hemisphere stroke, some patients can still correctly detect touch on their left hand – unless they’re simultaneously touched on their right hand in the corresponding spot, in which case they can’t feel the touch on the left. Strangely, the same thing happens whether the right hand is touched, or if they just see something close to the same spot.

Visuo-tactile extinction reveals a deep organising principle of the nervous system: perception reacts not just to what is present, but also to what we predict will be there soon. Prediction is a necessary compromise for the slow speed of neurons. A signal from a stubbed toe can take anywhere between a half and two seconds to make its way up to the brain, so our brains have found a workaround by anticipating what might be happening in order to provide a speedy response. Peripersonal space is no different, since anticipation allows faster reaction times and better sensory processing.

All the talk of speedy reactions can make it sound like protective behaviour is merely reflexive. But our protective response is also influenced by what we know about potential threats and their context. Hediger’s animals offer an obvious case: the zebra will flee from a nearby lion, but not from other zebras. A study by Giandomenico Iannetti and his collaborators showed that shocks to the wrist, which typically evoke defensive blinks, don’t occur if a thin wooden screen is placed between the wrist and the face. Knowing that what goes on at your wrist can’t affect your face, in other words, abolishes the protective response.

Peripersonal space isn’t just a zone you use to protect yourself from the world, but also from which to explore and act upon it. The area shrinks and grows depending on what you can do. When raking leaves, the leaves will be conceived as being in your immediate surrounding, even if they are quite far: the rake extends what counts as peripersonal. On the other hand, if your arm is immobilised (perhaps by a cast), then your peripersonal space shrinks closer to your body.

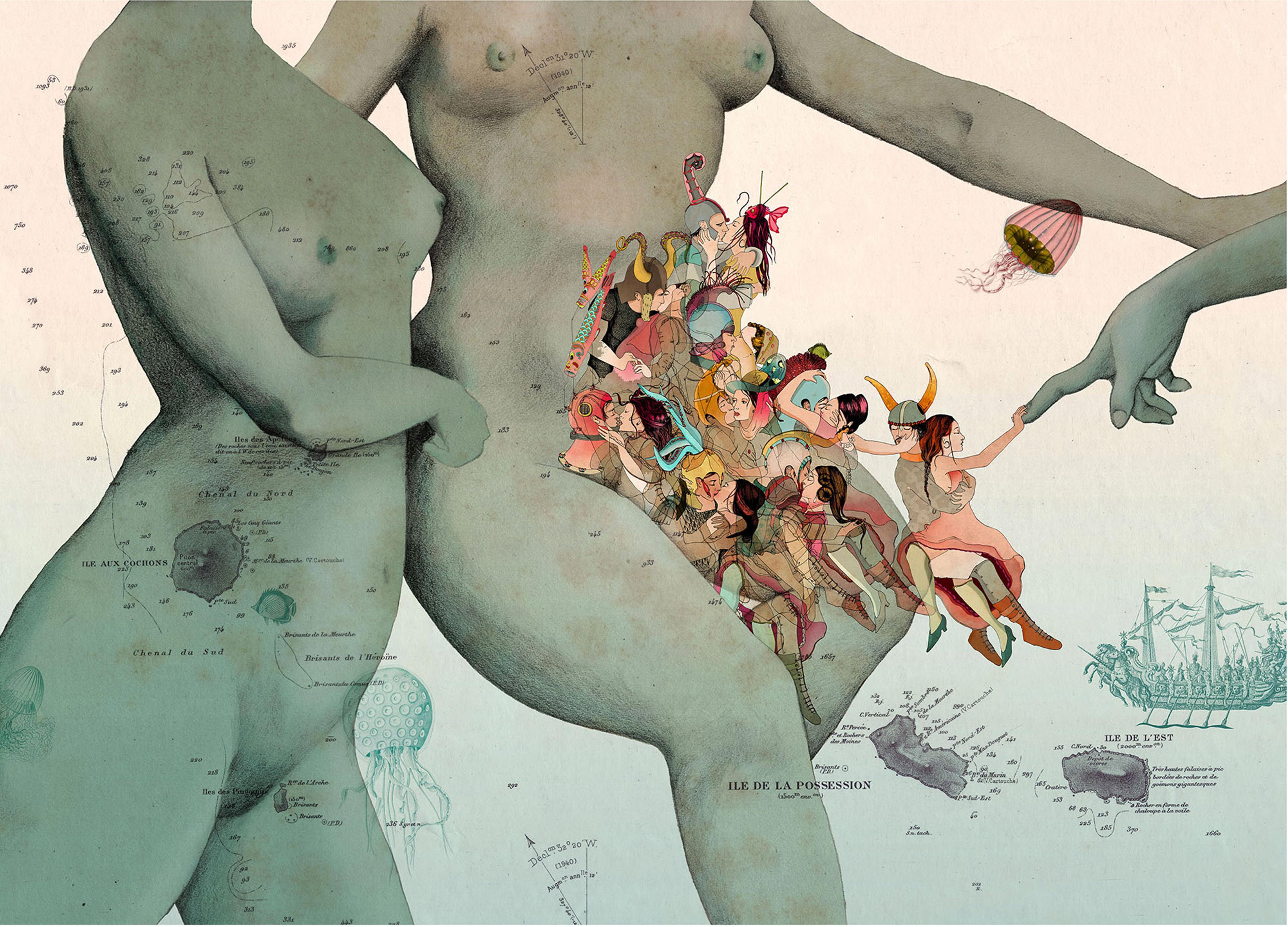

Peripersonal space thus exists in a curious dual relationship with both attraction and repulsion. Cutting tomatoes involves using a tool to extend yourself, and also protecting yourself from the dangerous knife right next to your fingers. But the world isn’t merely a space of dangers and tools – it’s also a world full of chocolate and raspberries, books and smartphones, friends and pets, all these things that we like and that we don’t want to avoid. No matter what Hediger says, we need to mate, to pick berries, and to raise a glass to our lips. Peripersonal space is also where the good things in life happen. We can’t survive just by building an impenetrable buffer around ourselves.

The fact that peripersonal space is crucial to shaping both positive and negative interactions shows something deep about the evolution of the brain. Peripersonal space depends on predicting contact, and contact prediction is useful both when that contact is welcome and when it’s to be avoided. Whether you’re dodging a ball or catching it, the same mechanisms appear to be engaged. In both cases, you need to be ready, and to be ready you need to anticipate what’s coming your way.

While peripersonal space first evolved for self-defence, then, its mechanisms have clearly been recycled to take advantage of opportunities in the immediate surroundings. This shift of function is in line with our general understanding of how evolution works by co-opting or recycling existing resources for new uses. ‘Evolution does not produce novelties from scratch. It works on what already exists, either transforming a system to give it new functions or combining several systems to produce a more elaborate one,’ as the Nobel laureate François Jacob put it.

This process is known formally as exaptation. While an adaptation is a new trait that was selected for the way it improved an organism’s fitness, exaptations retool existing useful structures for new purposes. A classic example of exaptation concerns the role of feathers in birds, which would have been originally selected due to their role in thermoregulation and only later co-opted for flight. Some cognitive abilities (maybe most of them) can also be conceived of as exaptations of existing brain resources: brain regions aren’t dedicated to a single task but are recycled to support numerous cognitive abilities. Recycling makes sense from an evolutionary perspective, since it’s more efficient than developing whole new neural systems.

As you might expect, though, using the same mechanisms for different purposes doesn’t come for free. There’s an increase in complexity, in the need for control, and in the possibility for confusion. It’s in the social realm that it might be most difficult to find the right balance between too close and too far.

Allowing someone to touch your neck is an incredibly vulnerable act

The way that humans respond to people or things that are in our space encompasses our assessment of their social significance. Necks are traditionally considered an erogenous zone. Yet the skin of your neck is actually one of the least sensitive parts of your body, at least in terms of pure tactile discrimination. Instead, as Graziano notes:

The neck is a special participant in the mating dance. It’s the part of the body most vulnerable to predators. The windpipe, the jugular vein, and the carotid artery run through it, as well as the spinal cord, so it makes a good handle for a carnivore. Powerful defensive reflexes normally protect it from intrusion by lowering the head, shrugging the shoulders, and lifting the arms to a blocking posture.

Our neck is ‘sensitive’ because we have a powerful instinct to protect it. Allowing someone to touch your neck is thus an incredibly vulnerable act – one that demands considerable attraction to overcome the ordinary drive to flinch, to cover, to protect.

By contrast, those who can tolerate a bit of distance certainly have an easier time of it when distance is demanded. The 19th-century philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer made this vivid with a metaphor:

A number of porcupines huddled together for warmth on a cold day in winter; but, as they began to prick one another with their quills, they were obliged to disperse. However the cold drove them together again, when just the same thing happened. At last, after many turns of huddling and dispersing, they discovered that they would be best off by remaining at a little distance from one another.

Schopenhauer suggests that people who can tolerate the cold will prefer to stay outside the prickly huddle altogether, where they ‘will neither prick others nor get pricked themselves’. Likewise, those who normally seem coldest and most aloof likely found the COVID-19 pandemic most tolerable.

In a time of social distancing, it can be easy to think of ourselves as little social atoms, with clear-cut boundaries. But the research on peripersonal space suggests quite the opposite. Our peripersonal space grows and shrinks depending on how we feel, and who we’re around; you can think of it like a balloon, expanding or deflating depending on your mood and your temperament.

The year 2020 was a worldwide social experiment in keeping our distance. Even in groups trying to adhere to the rules, you couldn’t help noticing that people didn’t neatly space themselves out on a two-metre grid. Nor did everyone feel the same way about how they maintained distance from others. Anxious people tend to find more of significance (and danger) around them, and studies show that anxiety can be measured by a corresponding expansion of peripersonal space. It’s also clear that individuals differ in their tolerance for physical and emotional closeness. Some look terrified if you’re a centimetre too close. Others crowd in queues as if nothing had changed.

Nor is people’s sense of appropriate distance evenly distributed in all directions. The early days of social distancing found people queuing in ways that left careful distance front-to-back and virtually nothing side-to-side. The animal welfare proponent Temple Grandin’s work with cattle showed that flight zones are often asymmetric: an animal needs more time to turn if it is to bolt from a threat from the side. Could a focus on airborne contagion – coughs, sniffles, sneezes – have made people especially focused on the distance from their face?

Our peripersonal space might be less like a balloon or bubble, and more like the tassels or fringes on a scarf

What’s clear is that peripersonal space doesn’t correspond to an objective region of space with a stable, well-defined border. Rather, peripersonal space is a subjective region that you represent as being directly relevant for you. It bears the traces of what – and whom – you have encountered. Closeness requires trust: it’s been shown that you tolerate the proximity of people whom you judge as decent more than those you think of as immoral. The invisible bounds of peripersonal space thus trace a delicate balance between trust and caution.

People who spend time near you also shape your peripersonal space in return. This isn’t merely a matter of protection, since social interactions require us to be able to work together, collaborate and delegate effectively. A study by the cognitive scientist Natalie Sebanz and her group, for example, shows the difference that working with a partner makes to the way you represent your surroundings. If you’re working alone or with someone unreliable, objects you’re working on that are close to you will feel like they’re in your peripersonal space. But if you work with someone next to you, who is paying attention to all the visual stimuli, the objects no longer feel like they’re in that buffer zone.

This result reveals how human evolution has been shaped by cooperation, both bodily and mental. Hunting large game with stone tools is a demanding endeavour: it requires constantly monitoring both prey and compatriot, with pointy bits flying between. Crafting stone tools is also surprisingly dangerous, and modern flintknappers who replicate palaeolithic techniques all bear the scars of their mistakes. The need to pass on this technology is one factor that probably drove the development of apprentice learning. The social aspect of learning embodied skills further underscores the importance of having a finely tuned sense of peripersonal space: imagine the challenges of sitting next to someone, holding a half-sharp flint core, trying to emulate what they’re doing while keeping your delicate fingertips away from the sharp edges.

In telling the story of peripersonal space, it seems reasonably simple to separate out the effect of people and objects, attraction and repulsion, physical danger and social threat. In the full story, however, all of these assessments are bound together, just as people and places and things are bundled up together in our emotional lives. Once we understand it more fully, the deeper story of the limits of our peripersonal space might reveal that it’s less like a balloon or bubble, and more like the tassels or fringes on a scarf – loose and sculpted by the changing breeze, adapting itself to a world of threats and opportunities.