If you share your home with a dog, you may have found yourself rolling your eyes or clicking your tongue at your furry friend in response to some outrageously un-wild behaviour. Your dog might daintily tiptoe around puddles, run away from squirrels, or refuse to go outside in the snow without a coat and booties. ‘You’d never survive without me,’ you might have gently chided her.

But what if you were to phrase this as a serious question for your dog: ‘Do you really think you would be able to survive on your own without my help?’ If your dog says: ‘Sure, why wouldn’t I?’ you might press her for some details: how would you stay warm? What would you do when it rains? What would you eat? And most importantly, wouldn’t you be lonely without me?

Your dog might tell you that she would simply go next door and live with your neighbour, who would likely provide the basics of food and shelter and even, probably, love. Annoyed by the apparent lack of loyalty, you might press your dog further and ask what she would do if there were no next-door neighbour. If, in fact, there were no humans whatsoever. Then how would she manage?

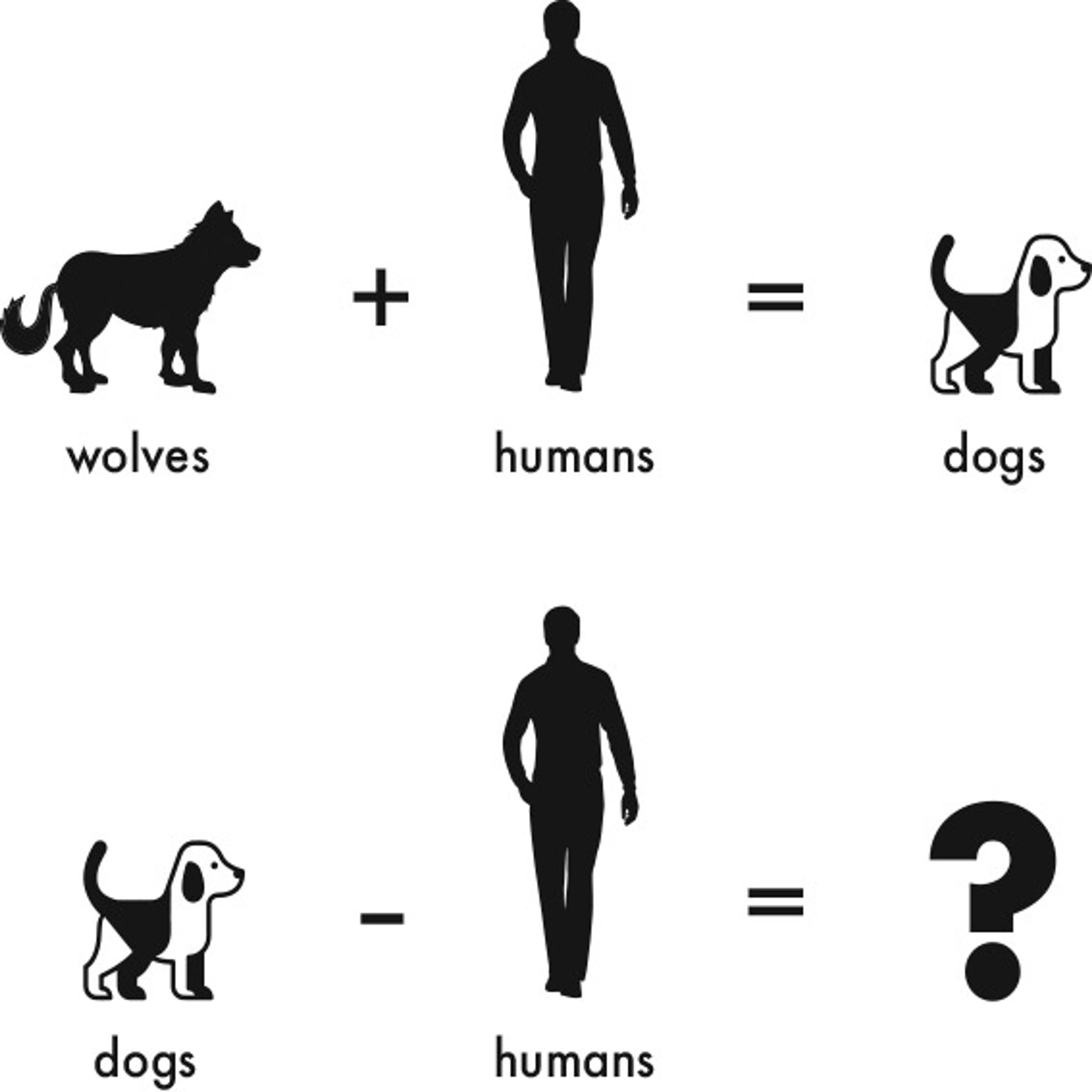

In our new book, A Dog’s World (2021), Marc Bekoff and I invite readers into an imaginary world in which humans have suddenly disappeared and dogs must survive on their own. We consider two key questions. First, could dogs survive without their human counterparts – are they still capable of living on their own, as wild animals, without help from and relationships with humans? Second, and perhaps even more intriguing, what are some of the possible evolutionary trajectories of posthuman dogs, as ‘artificial’ selection is replaced by natural selection? Would dogs look or behave anything like the animals we now call our best friends? This is a serious thought-experiment in speculative biology and one that can ultimately help us better understand who dogs really are. Thinking about dogs without us can help us understand who dogs are with us, and what they need from us, right now, to flourish and be happy.

If humans disappeared tomorrow, about 1 billion dogs would be left on their own. The first clue to whether dogs would survive is here, in the basic demographics of current dog populations. These billion dogs occupy all corners of the globe, exploit diverse ecological niches, and live in a wide range of relationships with humans. Although many people, when asked to picture a dog, will think of a furry companion curled up on the couch by a human’s side or walking on the end of a leash, research suggests that roughly 20 per cent of the world’s dogs live as pets, or what we call ‘intensively homed dogs’. The other 80 per cent of the world’s dogs are free-ranging, an umbrella term that includes village, street, unconfined, community, and feral dogs. In other words, most dogs on the planet are already living on their own, without direct human support within a homed environment.

Although the world’s 800 million free-ranging dogs have far more independence of movement and behaviour than the 200 million intensively homed dogs, and have developed a range of survival skills, almost all dogs on the planet rely on human presence for one key resource: food subsidies, either in the form of direct feeding and handouts or in the form of garbage and waste. The loss of human food resources would present the most significant survival challenge to dogs during the immediate aftermath of human disappearance and in the transition years into a fully posthuman future.

After some rough years, dogs would adapt to life on their own

If humans disappeared – along with their garbage, waste and stores full of bagged dog kibble – dogs would quickly have to find other sources of food. Because dogs are behaviourally flexible – and because they are dietary generalists – they could likely survive on a wide range of edibles, from plants, berries and insects to small mammals and birds, and perhaps even some larger prey. Their meal plans would depend on where they live, their size and their body shape.

The first few years after human disappearance would be challenging because of the abrupt loss of human support, and there would likely be significant canine die-offs. Dogs who had been living as pets might have a particularly hard time surviving because they lack the experience of being on their own, and might not have developed the skills they need for finding food and dealing with varied and unexpected encounters with dogs and other animals. After some rough years, dogs would adapt to life on their own. Dogs retain many of the traits and behaviours of their wild relatives such as wolves, coyotes and jackals; they have not ‘forgotten’ how to forage, hunt, find mates, raise young, get along in groups, and defend themselves. These skills would be put back to work.

The answer to our first question – would dogs survive the abrupt loss of human beings – is almost certainly yes, assuming dogs are left with a planet that hasn’t become completely uninhabitable because of the climate crisis. A more intriguing question is who dogs might become, once decoupled from humans.

The origin of modern dogs is still hotly contested among biologists, palaeontologists and anthropologists. But the general contours are in place. Dogs and humans have lived in close association for at least 15,000 years, and perhaps as many as 40,000 years or longer. The only canid species to have undergone domestication, dogs were also the first animals to be domesticated, and were likely the only animal to have been domesticated by hunter-gatherers, with other animals being domesticated after the development of agriculture. Dogs (Canis lupus familiaris) are descended from wolves (Canis lupus). And although dogs are genetically extremely close to wolves, sharing all but 0.2 per cent of mitochondrial DNA, they are most certainly quite different in both appearance and behaviour. One species can happily share your living room couch; the other will likely refuse such an invitation and be distinctly uncomfortable in your presence, and you in theirs.

This domestication process has strongly shaped the evolutionary trajectory of dogs up to this point. (It has also shaped the evolutionary trajectory of humans.) The phenotypic profile of dogs – their morphology, physiology, behaviour – has been deliberately shaped by humans through purposeful breeding. Alongside deliberate selection by humans for particular traits such as friendliness and attraction to novelty, there has also been indirect selection of other unintended traits, or what geneticists call ‘hitchhikers’. Direct selection for hypersociality, for example, introduced other traits, such as changes in pigmentation (spotted fur or white patches), floppy ears and curly tails, none of which are seen in the wild relatives of dogs. In other words, the idea that humans have created dogs is an illusion. We have splashed around in the dog gene pool, but the broader ripples from our splashes extend well beyond our conscious control or even our understanding. Indeed, the ethologist Per Jensen and his colleagues describe dog domestication as ‘the largest (albeit unconscious) biological and genetic experiment in history’.

In a posthuman future, this dramatic experiment would continue, but the parameters would change. Dogs would begin to drift in the currents of natural selection, and where these currents would take them is one of the great unknowns.

Still, we can make some educated guesses. As dogs become whoever they are going to become, they won’t go back to being wolves. The disappearance of humans would not result in a kind of reverse-engineering, where the domestication process rewinds and dogs de-evolve back to where they were before the first wolves tentatively reached out to human beings and vice versa. When dogs lose contact with humans, they will first go through a process of feralisation as they adapt to life on their own. Feralisation refers to changes in individual dogs, rather than to changes at the population or species level. Domestication, on the other hand, refers to changes that affect all individuals in a population. Individual dogs do not ‘de-domesticate’ when they are out of touch with humans – they feralise. Once all dogs have been free of human-directed selection for long enough that natural selection is acting on all the individuals in the group, they will become secondarily wild. (‘Secondarily’ here indicates that the population was once domesticated.) How many generations of human-free reproduction are necessary for the re-wilding of dogs to occur? Since we won’t be around, we’ll never know the answer to this facet of the biological experiment.

Dogs will need to find mates, engage in courtship, and bear and raise their young.

What we can confidently predict is that posthuman dogs are going to become something entirely, or at least largely, new. The ecological niches that posthuman dogs inhabit will be vastly different from the niches that their progenitors filled. The most consequential difference is that they will no longer have human food resources. Within that vacuum, many factors could influence posthuman dogs’ feeding strategies, including anatomical and physical constraints on what or who dogs can eat, the type of prey available in each location, the distribution of food resources within dogs’ home ranges or territories, seasonal variation in food resources, and competition with other animals. For example, small dogs would be able to hunt and feed on insects or berries, while such a diet wouldn’t provide adequate caloric intake for a large dog. Different feeding strategies might evolve over time depending on ecological niche, local food availability, and competition with other animals. Dogs’ diets would, in turn, influence how they evolve over time. Eventually, different populations of dogs might even become distinct species, using different feeding strategies to fill a range of ecological niches.

Reproductive strategies will also need to evolve quickly. Dogs will need to find mates, engage in courtship, and bear and raise their young. The mating and reproductive strategies of posthuman dogs would likely not need to shift as dramatically as their feeding ecology. Nevertheless, there could be some interesting changes as natural selection favours strategies leading to greater breeding success in the absence of humans. These might include more prolonged and ritualised flirting, a reversion to one heat cycle per year rather than two, and greater involvement of mothers, fathers, aunts, uncles and other alloparents in the rearing and protection of youngsters.

Many different forms of social organisation could emerge and work in a world without humans, including the formation of bonded pairs, small groups and larger packs. Alternatively, some dogs may live mainly solitary lives, coming together with other dogs only when necessary. Whatever kind of social life they have, dogs will need to sharpen their social skills, including communicating intentions and resolving conflicts, and will need to learn from one another. Skills developed during puppies’ early socialisation period and adolescence will be particularly important. The inner lives of posthuman dogs will also change as they evolve the cognitive skills and emotional intelligence required to interact with other animals and make them successful members of wild communities.

What might a posthuman dog look like? It’s hard to say, because morphological features will evolve in response to ecological pressures, feeding ecologies, and distinct features of the ecological niche that a given population of dogs might fill. Dogs are already the most morphologically diverse mammalian species on the planet. Think of the huge size difference between, for example, the teacup Maltipoo and the Irish wolfhound. One possibility is that dogs will eventually all become of medium size – say 35 lbs (15 kg), give or take. An equally viable possibility is that dogs of the future will speciate over time into smaller and larger types. The shape and size of physical characteristics such as ears, tails and noses will similarly evolve in response to unique demands of ecological niche, feeding ecology, mating strategies and social structure. To take just one example, the shape and size of ears will represent a set of tradeoffs reflective of the competing demands of climate, geography and feeding ecology, among other things. Bigger ears may pick up sounds better than smaller ears, and would aid dogs in locating prey, but they might also be problematic in very cold temperatures because there is more surface area for heat loss. In cold climates, smaller ears and slightly less acute hearing might be worth the tradeoff for protection against the cold.

Natural selection will quickly weed out physical traits that are maladaptive, such as extremely foreshortened snouts, excessive skin folds, and extremely long or short limbs. Floppy ears and curly tails would also likely disappear because they inhibit dog-to-dog communication and serve no functional purpose; so, too, would spotted and bi- and tricoloured coats.

Dogs have been selectively bred by humans for certain behavioural traits, including a general propensity for friendliness and malleability, and breed-specific functional skills such as pointing, fetching, herding and guarding. Selection for these traits has been driven by an interest in the physical characteristics of dogs, by the usefulness of these traits in relation to human pursuits, and, over the past century or two, by human aesthetic whims and fancies. Taken outside the context of human-canine relations, some of these physical and behavioural traits may serve dogs well. Others not so much.

It is hard to know how some of the behavioural traits that have resulted from domestication, such as hypersociability and attention to human gestural cues, might be repurposed by posthuman dogs, and whether these traits will be useful or maladaptive. Who knows, for example, whether the facial muscles that allow dogs to make ‘puppy dog eyes’ to solicit food or attention from people – musculature that is absent in wolves and other canids – will have any use in a posthuman world.

Would dogs actually be better off without us? This could be a difficult question to entertain if you live with dogs, love dogs and stand in awe of the enduring friendships humans and dogs can form. But it is worth trying to imagine, for a few moments, not only what your individual dog might lose and what she might gain, but also what all the dogs who currently share the planet with us might lose or gain if they had the world to themselves. And what about the posthuman dogs of the future who never knew life with humans? Maybe dogs as a species would have a better go of things if the 20,000-year-long domestication experiment were called off once and for all. Dogs would face challenges living on their own, but a posthuman world is also full of what you might call ‘dog possibilities’.

As part of our thought-experiment, therefore, we made a tally of all the possible gains and losses dogs might experience if humans were to disappear tomorrow. Here is a condensed list:

What dogs have to gain from human disappearance:

- Freedom of physical movement (no human constraints, such as collars, leashes, fences, cages)

- No more intensive captivity, such as in puppy mills, laboratories or dog-meat farms

- No more experimentation

- No more forced breeding

- No more artificial selection for maladaptive traits

- Ability to act independently and make free choices

- Freedom to socialise with other dogs

- Freedom to mate with whom they choose and when they choose

- No fear of or stress from human punishments, violence, confinement, unpredictability and inconsistency

- Ability to engage their full range of natural species-specific behaviours

- Lower levels of obesity

- Potentially better nutrition

- Greater range of sensory experiences (eg, can more fully use olfactory sense)

- Natural level of hormones and development

- Physical activity budgets would be chosen by dogs themselves, not by humans

- No desexing

- No surgical mutilations, such as tail docking, debarking and ear cropping

- Reduction in breed-specific genetic disorders

What dogs have to lose from human disappearance:

- No veterinary care

- No pain management (medicines, massage, acupuncture, palliative care, pain medications, etc)

- No vaccinations

- No human-provided control of parasites

- Potential exposure to diseases

- Loss of physical comfort

- No regular meals

- Potential for nutritional deficiencies

- Greater exposure to predation

- Greater exposure to the elements

- No human-provided safe zones

- No human food resources

One of the big surprises for us was that the gains column was significantly longer and more robust than the losses column. And this got us to thinking: if dogs really have more to gain than lose, are there some ways in which we might alter, in the real world, the parameters of human-canine interactions that address some of the problems highlighted in the gains column? Indeed, the gains column can help bring into focus some of the ways humans make life hard for dogs, particularly pet dogs who live within our homes. Our pet dogs generally do not get to pick their friends or their family and do not get to decide when or how to interact with others; they don’t have the opportunity to choose a mate and raise a family, unless we label them ‘breeding stock’, in which case they have no choice; they don’t get to move about freely, work to find their own food and shelter, or respond to varied stimuli from the environment. Moreover, humans breed and buy dogs with maladaptive traits that not only make posthuman survival unlikely but diminish their lives right now. The most obvious example here is the breeding of dogs with extremely foreshortened skulls, such as French bulldogs, who suffer from breathing difficulties and high rates of respiratory disease.

Imagining a future for dogs without their human counterparts is an interesting exercise in biology, but the real value of the thought-experiment is that it can help us think more clearly about who dogs are in the present and this, in turn, can clarify the moral contours of human-canine relationships.

The most important effect of thinking about posthuman dogs, and how they might flourish in the absence of us, is to decentre the human. We tend to think of dogs through the lens of what they mean to us (they are good companions, beneficial for our health, a salve for our loneliness, useful for work, sport and entertainment). But often the lives we ask them to live in our presence are a pale reflection of what they might be.

So, how can we help dogs live experientially rich and interesting lives now, within our midst? Those who live with homed dogs ought to consider allowing their dogs to engage in a wide range of species-typical behaviours. Humans can be more thoughtful in their approach to living with dogs if we use the best canine science to understand who they are. People who live with a companion dog often benefit from reading one of the many excellent and accessible books on the science of dog emotion and cognition, often based on research conducted within canine cognition labs. They learn about how their dog experiences the world – how, for example, dogs ‘see’ the world primarily through their noses. Knowing this, we can do our best to provide opportunities for our dog to use her incredible olfactory capacities, for example by letting her linger over smells when out for a walk or letting her have plenty of time off-leash to follow her own olfactory agenda.

Perhaps even more useful for the average dog guardian would be an exploration of the growing body of research by scientists who study feral and free-ranging dogs. Indeed, one of our central aims in A Dog’s World was to bring this research to a general audience. Here, in studies of free-ranging dogs, we can begin to see dogs not as domesticated playthings but rather as animals. Moreover, we see them as animals situated within ecological communities, where the centre of their world is not necessarily us. Learning about the lives of dogs on their own, we begin to grasp the entire range of canine possibilities and can understand how limited the four walls of a human home really are.

Obsessively helicopter-parented dogs have their ability to engage in normal behaviours seriously compromised

As one small example of this, consider how dogs use space. Biologists use the concept of home range, which was defined in a 1943 paper by William Henry Burt as ‘that area traversed by the individual in its normal activities of food gathering, mating, and caring for young’. Research on the home range of free-ranging dogs shows wide variation, with some dogs having a home range as small as half an acre while others have a home range as large as 7,000 acres. In contrast to free-ranging dogs, intensively homed dogs are highly constrained in the ways they are allowed to use space: they don’t generally have anything that approximates a home range, are rarely allowed to roam at all, and are considered very lucky if they have a half-acre backyard.

Another example is the role of male dogs in parenting young. Among intensively homed dogs, males are rarely observed playing a role in parenting. But is this because male dogs don’t naturally parent their young? Or is it because the ways humans breed dogs typically don’t allow male dogs the opportunity to be fathers? Although research on fathering by free-ranging dogs is mixed and male dogs don’t always appear to be involved, several observational studies found male dogs playing a role in feeding, protecting and teaching youngsters. If parental care is part of the suite of natural behaviours for male dogs, should we reconsider the ways we orchestrate the breeding and raising of pups to allow male dogs the chance to be fathers?

The research on free-ranging and feral dogs, as well as other species of canid, sheds light on the remarkably interesting, full, exciting lives of dogs on their own. Dogs have a wide range of natural habitats and live alongside humans in diverse ways. But some habitats are decidedly more captive and constricting and do not allow dogs to be dogs in any meaningful way, such as laboratories, dog-meat farms and puppy mills. Some habitats are less obviously captive, but nonetheless may greatly limit a dog’s ability to live an interesting life. Little dogs who are bought as fashion accessories, and who have their nails painted and are taught to ‘go’ inside on fake turf, are not really allowed to behave like dogs. Dogs who are obsessively helicopter-parented by their human guardian also have their ability to engage in normal dog behaviours seriously compromised.

It isn’t all that pleasant to think of a world in which we’re no longer here, but there are many reasons to believe that, when we’re gone, dogs will survive and life will go on. And it is healthy for us to begin decentring the human now. When we decentre, then real, fruitful non-anthropocentric thinking can begin. In imagining who dogs might become without us we may gain fresh insight into who they are now and how our relationships with them can best benefit us both.

We may ask our dogs, jokingly: ‘What would you do without me?’ They may indulge us with a wag and bark, all the while imagining the possibilities.

This original essay draws on the book ‘A Dog’s World: Imagining the Lives of Dogs in a World without Humans’ (2021) by Jessica Pierce and Marc Bekoff, published by Princeton University Press.