By the time you read this essay, no matter the hour of the day, you will likely have already made some kind of choice: coffee with skimmed milk, whole milk, cream, or black? Sugar or no sugar? Tea instead? Personalised, preference-based choice is, at present, a deeply familiar aspect of life in much of the world, though perhaps most markedly so in the United States, where I live and work. It is also something people don’t generally spend a lot of time discussing, in part because it feels so ordinary. People around the globe shop for everything from housing to vacations to, yes, caffeinated drinks. They pick what they want to read, what they want to listen to, and what they want to believe. They vote for favourite candidates for office. They select friends and lovers, fields to study, professions and jobs, places to live, even insurance plans to hedge their bets when something they cannot choose occurs.

Perusing a menu of options to decide what best matches individual desires and values – which is what we generally mean today by making a choice – is a key feature of modern democratic and consumer culture alike. It is also an exalted one. People may disagree about what the possibilities should be, but rarely about the principle of maximising arenas for choice-making or the options themselves. For many of the world’s citizens, this is simply what freedom feels like.

Yet, as you may have also felt at various moments, abundant choice isn’t always so straightforward. Behavioural economists point out that most people are actually pretty bad at making decisions of this kind (which explains the appeal of return departments and divorces for when things don’t go as hoped). Philosophers and political theorists say it promotes selfish individualism and discourages collective action around issues that affect us all. And sociologists add that societies that prize choice too much tend to blame those with only poor or limited options for their own misfortunes. So much for choice as consistently synonymous with freedom.

What is strange, though, is that few of these critics ever really question either the centrality or the value of choice-making in contemporary life. On the contrary, they tend to make their case as if people everywhere had always spent their days doing things that feel commonplace in capitalist democracies and, indeed, hankering for more such chances. But for the historian, it is obvious that this entire phenomenon is culturally specific. There are people around the globe even today who actively resist this framing of freedom. What may be more surprising is that granting this special status to choice-making is also a relatively recent development even in Western Europe and the United States, not to mention the rest of the world.

So how did we get to this point? How did choice become a proxy for freedom in so many domains in modern life? As we discover more and more about our troubles navigating it, we might also wonder if there are other, better ways to be free.

Though the explosion of choice has largely been a 20th-century phenomenon, the full story is a long one, going all the way back to the 17th and 18th centuries. Personal choice, as both experience and term of art, got its start in two quite distinct early modern spaces.

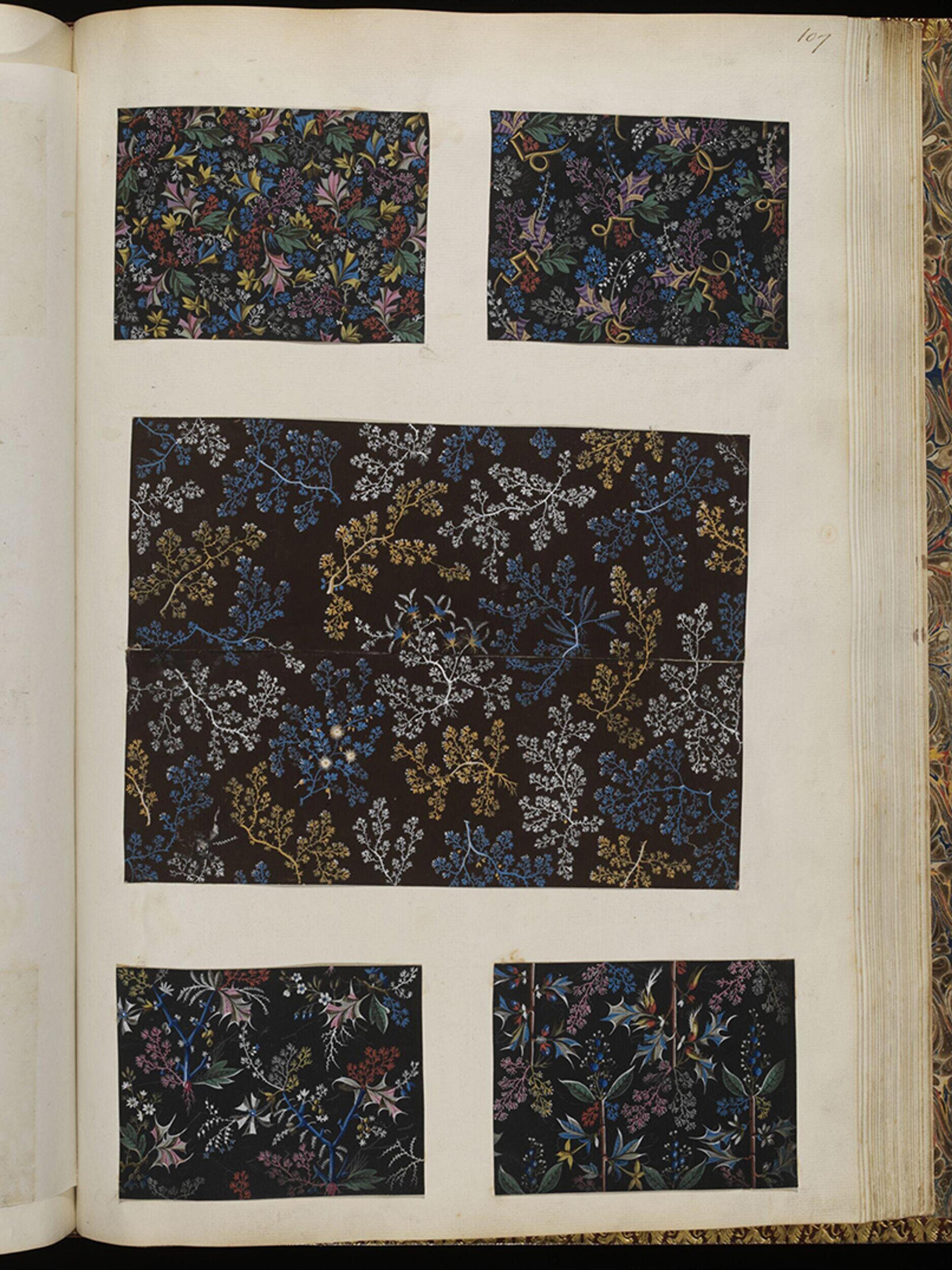

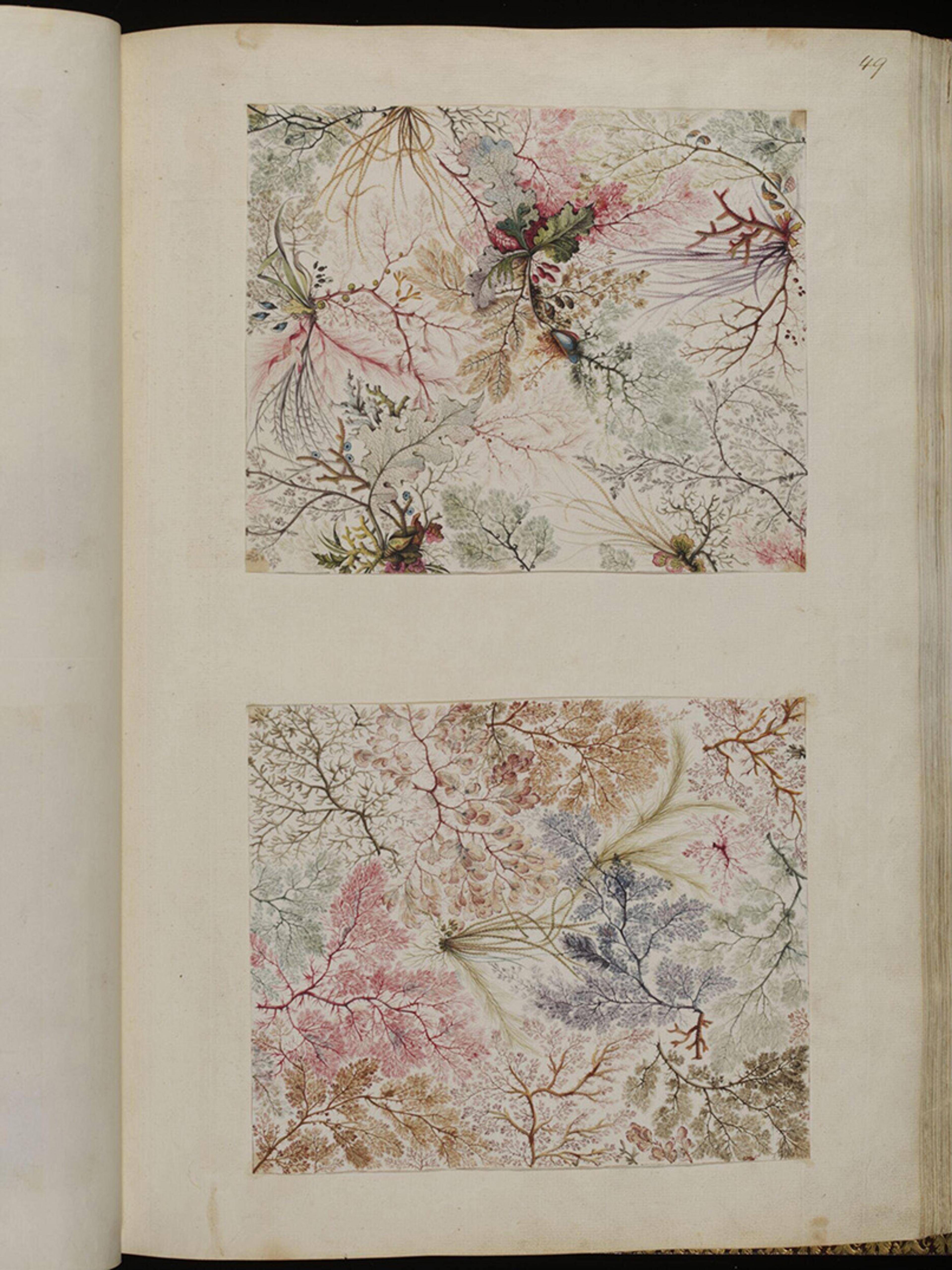

One is the realm of the shop. Fuelled by the building of colonial and interior trade networks, new goods started to enter cities and towns as early as the 17th century, first in Western Europe, then in the New World, and gradually in their hinterlands too. Particularly significant among those goods were patterned and brightly coloured textiles called calicoes, originally from South Asia, whose price point made it possible for ordinary people to have the novel experience of selecting from among different designs for clothing or home furnishings. Checks? Flowers? Stripes? Purple or green? The decision could, distinctively, be based on nothing more than personal preference. For at the same time, a leisure-time activity blossomed, first at auctions in temporary locations and then increasingly in fixed destinations called shops, in which consumers were invited to peruse a display of the options for sale before ever opening their purses.

Even people with limited means started to engage in such new activities as trying out different preachers

The English-language neologism ‘shopping’, as opposed to provisioning, took off in the second half of the 18th century precisely to describe this newfangled business. We now also call it consumer choice. The customer learned from all of this browsing and weighing the possibilities to ‘make a choice’ – which is to say, an aesthetic as well as a practical determination en route to purchasing – from what were often already described as a set of ‘choice’, or pre-selected, goods ripe for picking.

Designs from an album for printed textiles (1788-92) by William Kilburn. Courtesy the V&A Collection, London

The post-Reformation fracturing of Christianity, combined with the Protestant tradition of ‘freedom of conscience’ or ‘religious choice’, gradually produced a sense of ideas and beliefs as being similarly up for selection in a pluralist world. With the double emergence of Enlightenment notions of tolerance in Europe and of the Great Awakening religious revival in the British colonies, even people with limited means started, on both sides of the Atlantic, to engage in such new activities as trying out different preachers and churches where congregations had become voluntary communities, attending varieties of public lectures, and picking books from lending libraries and sales catalogues. These, too, were learned recreations, ones that soon revolved around secular as well as sacred notions. Consider Jane Austen’s fictional heroine in Mansfield Park (1814) who, when she gets up the nerve to subscribe to a lending library, is, in Austen’s lightly satirical telling, ‘amazed at her own doings in every way, to be a renter, a chuser [sic] of books!’ From such actions, the stage was set for intellectual choice as well.

Between the late 18th century and the First World War, choice continued to expand its domain, encompassing the selection of other people, from marriage partners to employees to political representatives, too. At the same time, it became subject to ever more rules and strictures, formal and not, so as both to tame its potential for undermining the social order and to make it work.

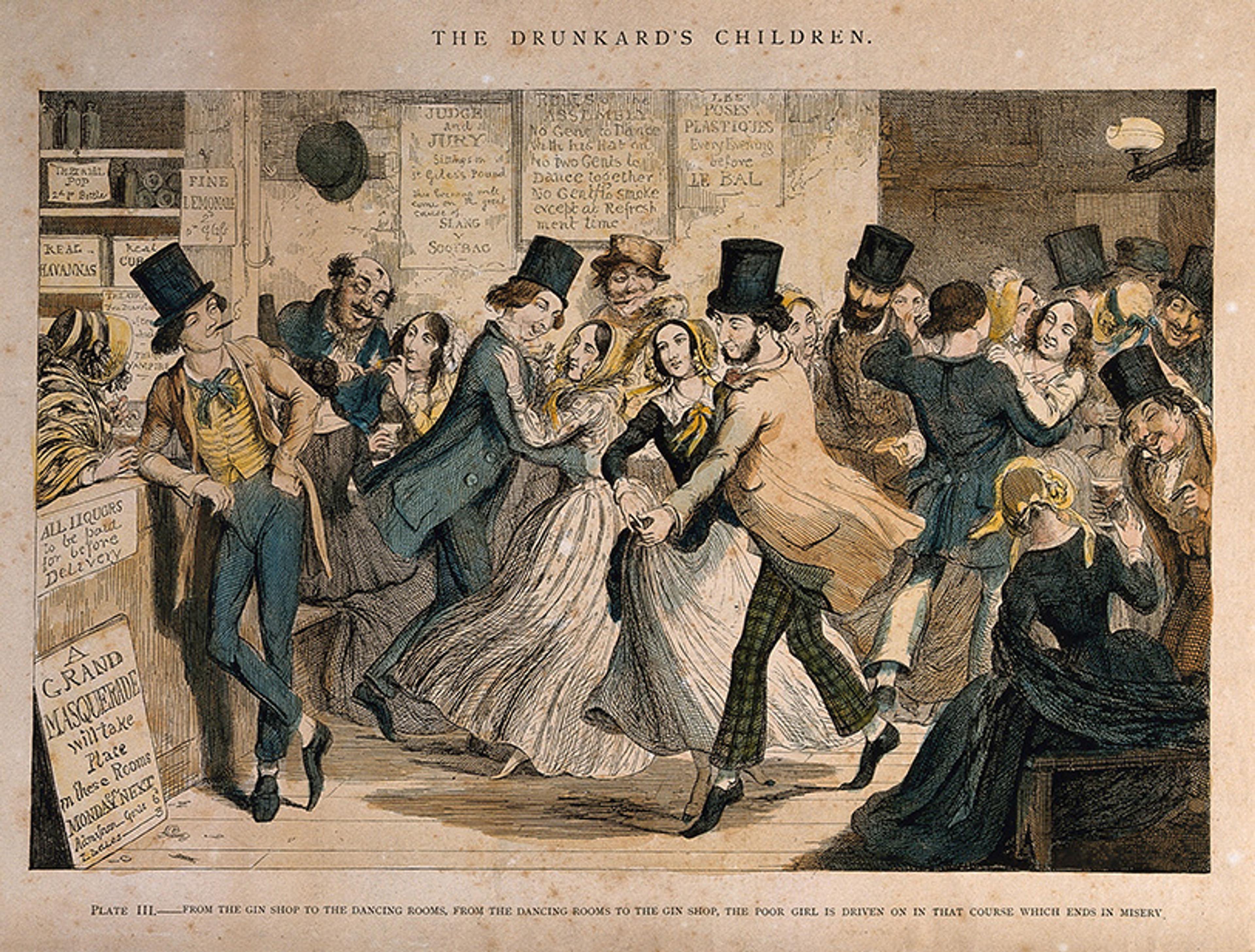

In the course of the 19th century, choice increasingly entered the romantic and sexual lives of urban men and women, though with significant gender distinctions when it came to the rules, creating affective and bodily choice as well. This was a development tied very much to the rise of both the idea of companionate marriage – spouses who consent to marry out of mutual affection or even attraction – and an elaborate etiquette about how to identify and court possible partners in a world in which everyone didn’t already know everyone else. From Santiago and Chicago to Paris and Stockholm, and from working-class ticketed dance halls to private soirées for the elite, balls, in particular, became places for organising and evaluating the options in a world in which both young men and young women had been given the power to contract freely for a spin around the dance floor – and also, potentially, for permanent coupledom in the form of a marriage (aka ‘The Choice’, though a marriage contract would technically mean the end of sexual choice once it was signed and sealed). Employment saw a similar kind of transition insofar as it, too, became increasingly a matter of sorting mechanisms, markets and contracts.

‘From the Gin Shop to the Dancing Room’ (1848) by George Cruikshank. Courtesy the Wellcome Collection

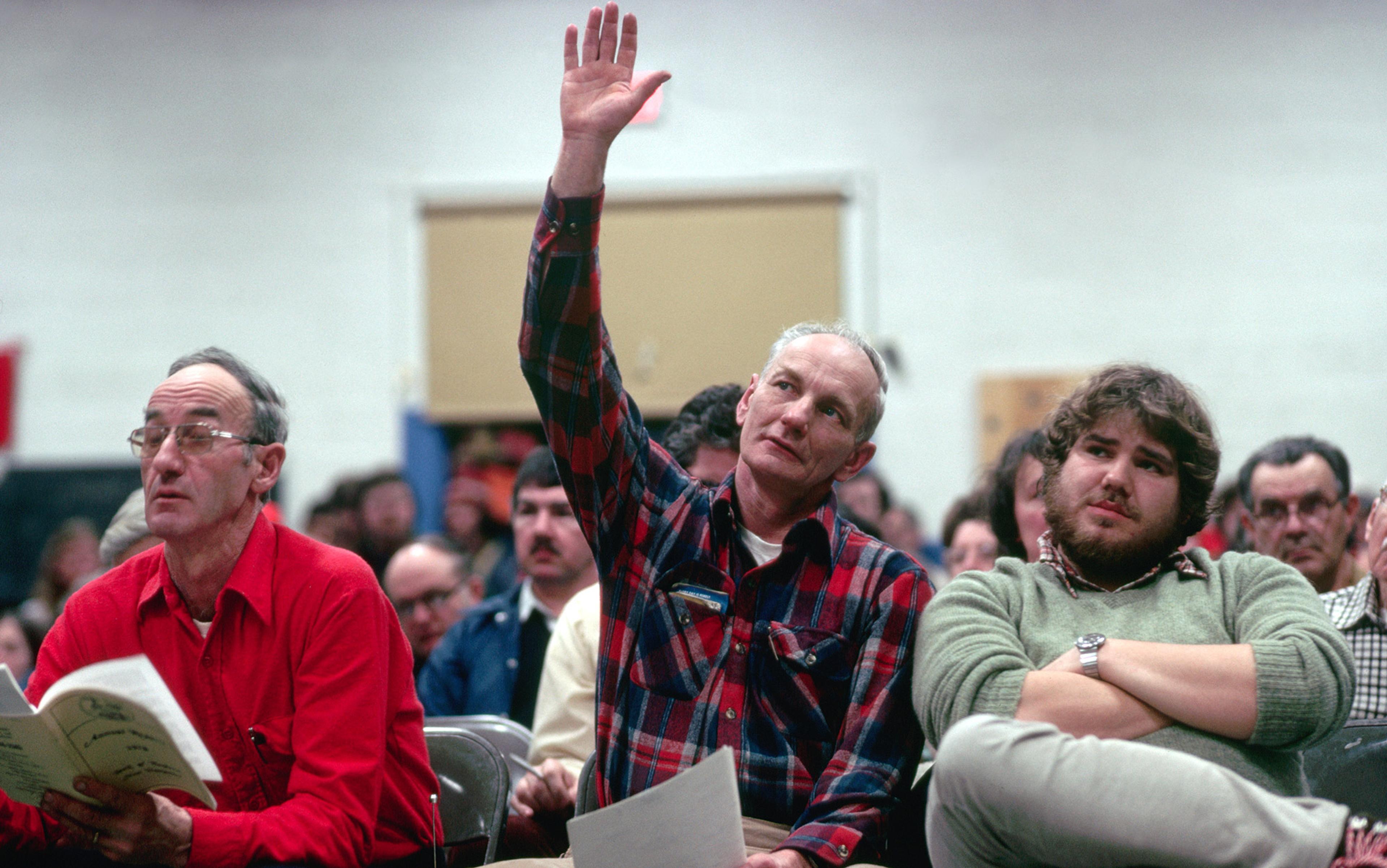

Finally (and surprisingly late), a similar form of choice came to politics in the form of new voting practices as well as an increase in formal laws to go with them. It is well known that the 19th century was marked by intense debates, from Central Europe to Latin America, about who should be able to vote as new democratic norms spread to many parts of the world. Much less well remembered is the rise of intense discussions about how all these new voters should go about the business of suffrage, especially when it came to the moment of choice itself. Voices in favour of secret balloting, like the Sons of Liberty in New York City, had made themselves heard by the end of the 1760s. But it wasn’t until another century had passed that this mode of voting, rooted in the idea of the protection of internal personal preferences from outside pressure, became the international gold standard, instituted first in Australia in the 1850s (hence what is sometimes still called the Australian ballot) and then by a host of other nations around the globe in the decades just preceding the First World War.

Psychiatrists, marketing experts and economists devoted themselves, in different ways, to the study of choice-making

Even at the time, commentators were amazed that this transformation took place with so little upheaval. That may well be because the change to secret, individualised voting diminished the rowdiness and violence so often previously associated in many places with popular and considerably more communal elections. But surely it was also because, by the time this shift occurred, it seemed to bring elections into line with so many other kinds of 19th-century leisure-time activities. The secret ballot allowed for the same sorts of choice-making to be enacted when it came to candidates, though with the results eventually aggregated into group choice, as it did for other forms of picking – overcoming the longstanding objections of even liberals like John Stuart Mill, who worried that the last stronghold of public life would in this way be privatised. Only the workplace would remain largely immune. In effect, if the initial age of revolutions in the 18th century introduced popular sovereignty based on elections in the first place, we might think of this as the moment of a second age of democratic revolution.

Naas Valley, Australia, 1963. Courtesy the Museum of Australian Democracy

But the 20th century added its own finishing touches to the story of choice. The ranks of choosers continued to expand, albeit highly unevenly, to include women, poor people, sometimes even children, especially in places where mass goods, from newspapers to chewing gum, became widely available. So did the ranks of ‘choice agents’, the people creating the menus of options, inventing the rules, and directing the activity itself. Beyond shop owners, itinerant preachers, dancing masters and political party officials, now new kinds of social scientists came to the fore. Psychiatrists, marketing experts, economists: in different ways, they all devoted themselves to the study of choice-making, exploring who makes what choices under what conditions and with what effects, along with how individuals and groups could be steered to make better ones. Ordinary people participated in this work every time they sat on a couch for a therapy session or filled out a survey card or took a multiple-choice exam. Together, researchers and their everyday subjects, male and female, invented sciences of choice, further entrenching the idea of humans as, fundamentally, choosers.

Needless to say, the rise of the internet has only expanded this model. Today, the sheer number of both choice-making opportunities and options has grown exponentially, whether we are talking about music or vacuum cleaners. The nature of our choices has also changed. Before the age of shopping for goods and selecting ideas had really gotten underway, most choices were structured around doing the right thing rather than the wrong. Since then, choice has increasingly become value-neutral, a matter of one’s own interior preferences being externalised in the act of selection. Moreover, choice has become more and more important to conceptions of human flourishing. Once, picking from menus was of relatively little significance, especially since freedom was imagined in the Western tradition well into the 18th century more often as a matter of not having to make many choices or strive too much thanks to being born with the status of an independent person. Over time, however, choice became a means of achieving the liberty to shape one’s life as one saw fit. It also became a key signifier of being a full-fledged, autonomous person worthy of respect by others. Since the end of the Second World War, we might say that it has become a value unto itself, widely celebrated from billboards to international human rights decrees as the meeting point of capitalism and democracy. When then French presidential candidate Emmanuel Macron said, in 2016, ‘I believe deeply in a society governed by choice,’ he was in a certain sense uttering what had become a banality.

This is a story that has not been told before, even as some of the details may feel familiar from lived experience. It is also an essential story to grapple with if we want to try to understand what has been gained and lost from an investment in choice as the defining feature of ‘free time’ as well as a basic understanding of freedom. How have people, individually and collectively, benefitted from this mushrooming of options and opportunities for choice – and how and when has choice led us astray? This is a question that behavioural economists and all others who take our current actions and investments as constants have largely failed to ask.

On the one hand, it is easy to read this narrative as a tale of liberation. Take feminism. Women in Europe and its outposts got their first real taste of the modern form of choosing as shoppers for ribbons, fabrics and other sundries, as late-18th-century novels – and especially those written by and for women – make very clear. Certainly, both women and this new kind of value-neutral, preference-based choice-making were quickly tainted by association with each other; the coquette was a much-mocked figure of the 18th and 19thcenturies, a stereotype of a woman who relishes her own choices a little too much and isn’t very good at them either. But as new forms of individualised selection became more important to life beyond the textile purveyor’s shop, and as men got in on the game as well, an expanded repertoire of choice, including in ideas, reading matter, marriage, children, career and finally politics, became one of the key aspirations for women looking to break free of their traditional constraints.

Female suffrage, for example, could be advocated at the start of the 20th century as simply an extension of women’s already existing capacity to make a selection from a list-like menu. By the start of the 1960s, the American feminist Betty Friedan could argue that women’s full liberation required them to follow their male counterparts in seizing ‘the power to choose’ in their personal lives too, including in forging ‘an identity’ beyond housewife. And a decade later, mainstream abortion rights advocates, not surprisingly, took the same tack, imagining limited resistance to a focus on choice. Who, after all, could object? Behind the 1970s feminist idea of ‘a right to choice’ when it came to motherhood was the argument that no one should be compelled to pick this solution – abortion – for themselves; the law now simply ensured that everybody could, as needed, determine which of the possibilities on offer seemed like the best option by their own criteria. Plus, having choices meant the essential opportunity to reassert one’s standing as author of one’s own destiny – a point sometimes made by stateless people today as well. No wonder the ability to choose has become a key factor in global happiness indexes.

A market model for governance would, ironically, mean the end of democracy as we know it

But the abortion debate of the 1970s also illustrates some of the limitations of this framing. Soon after the passage of the Roe v Wade US Supreme Court Ruling legalising abortion in the early months of pregnancy, an emerging Right-wing coalition landed on a clever strategy for opposition, arguing that the ‘life’ of the fetus outweighed mere ‘choice’ on the part of the mother. In other words, in feminists’ enthusiasm for having choices, the moral dimension of what was being chosen had been pushed to the side, leaving behind a very thin foundation for a major policy matter. And from the Left, and especially from Black feminists, came the argument that choice itself was meaningless, an empty promise, unless it was to be accompanied by a commitment to meeting women’s basic needs, whether that meant the money necessary to travel and pay for an abortion, or greater financial and institutional support for mothers after their children were born. In this sense, they too warned of the dangers of the shopper and shopping as models for all our activities, even when couched as rights.

Now we are seeing some of the fallout of this debate writ large. Today, a far-Right ‘dark enlightenment’ movement imagines a market model for everything, including governance, which would, ironically, mean the end of democracy as we know it. At the same time, significant pushback around the world against feminism, and now against gay and trans rights as well, has become emblematic of the rejection of a larger vision of freedom rooted in personal choice. As a result of democracy-promotion and global capitalism, almost no one in the world currently stands entirely outside the choice-as-freedom paradigm; it has gradually enveloped even those with very limited ability or opportunity to choose or with only rotten choices before them. Voting, for example, is near universal today even in places like Russia, where it is a sham. But an emphasis on choice as a form of liberation has occasioned serious resentments in different sectors and geographies, where it can seem a direct threat to other, more communal values and needs.

Indeed, even in democracies, choice can sometimes seem to be not only an illusion (is there any real difference between the scores of toothpastes or breakfast cereals in contemporary supermarkets?) or a headache to contend with, but a regressive force. Think, for example, of people who took up the pro-abortion rights phrase ‘My body, my choice’ to protest mask or vaccine mandates during the COVID-19 pandemic, even as they were told that the point of both actions was to limit the spread of the disease and advance public health more broadly. Or consider how the US president Donald Trump’s current claims to be restoring the American people’s ‘freedom to choose’ in the market for cars and appliances will require gutting environmental regulations and thus advancing climate change in ways that will negatively impact all of us. It’s not just that we don’t always know our minds. It’s that choice in its current incarnation isn’t, in fact, always freeing.

So where does this leave us? The answer is not with one or the other of these visions. But considering the history of choice should make us more self-conscious the next time we are fretting over whether to pick the oat milk rather than the half-and-half, not to mention one train ticket or candidate for office or college course over another. We might instead ask ourselves: when, collectively, should we be invested in individual choice as a good way to solve a shared problem, and when not? And when should I, as an individual, try to maximise the opportunity to make choices about my own life versus not doing so? Most of all, though – as we struggle with both choice overload and the failures of personal choice to help us solve some of our biggest problems, including the rise of forms of authoritarianism directed squarely against choice – thinking about our attachment to choosing off menus should make us wonder what other possibilities for defining freedom might be lurking out there. In the past, for example, freedom has sometimes been imagined as a release from oppression or as an act of pure imagination, alternative visions we might want to bring back into circulation. As it turns out, choice doesn’t always produce freedom, and freedom itself often looks very different.