There is a line in J G Ballard’s book The Atrocity Exhibition (1970) that strikes at the heart of the issue of free will versus fate. Ballard writes: ‘Deep assignments run through all our lives; there are no coincidences.’ It is an arresting line — and no doubt many of us at one time or another have felt just this way about our lives, that they have a fated quality to them — but just what these ‘deep assignments’ consist of is unclear. The issue of free will versus fate might, for many people, feel a little rarefied, and irrelevant. Yet it seems to me it is absolutely crucial to how we approach the countless dilemmas that confront every one of us each day.

Perhaps it’s peculiar, but this question has vexed me for as long as I can remember. At one point in my life, this challenge pretty much sent me crazy. In the late 1980s, when I was studying history at university, I found myself grappling furiously with the question of why things happened — this question being, really, at the heart of all historical analysis.

Why did the Russian Revolution happen in 1917 rather than the ‘first time round’ in 1905? What caused the Second World War? Was it ‘larger historical forces’? Or just individuals making individual decisions? And, at the same time, in my own life — after I had split up with my then long-term girlfriend — I was left asking, what had I done to make that happen? What did I have to do to get her back? Was it in my control?

After three years, I was no wiser than when I started. Did we choose freely? Or were we just victims of larger historical, social and biological forces? It was impossible to tell. What I did realise was that philosophers had been struggling with such questions for thousands of years, but were no closer to understanding the answer than they were when they started out. Today, the consensus among most modern physicists, chemists and biologists is that free will is impossible — it is simply an illusion generated by a consciousness that is itself illusory. This explanation didn’t satisfy me. After all, if consciousness is an illusion, who is generating the illusion, and who is perceiving it as an illusion? For me, mechanistic determinism — that there is a sort of fated cause and effect at play in the universe, with no room for choice — raised more problems than it solved.

Consider your breathing: are ‘you’ breathing, or is breathing happening to you?

It also just felt wrong. I felt so sure that I could decide whether or not to drink the glass of water in front of me that I would find it impossible to be convinced otherwise. That direct experience of reality is valid, particularly since it also takes into account the fact that I might drink the water without consciously choosing to, without thinking about it first.

At the same time, it seemed impossible to believe wholeheartedly in free will. At one level, I intuited that there were paths that you just ‘had’ to take, even if you didn’t want to. When I decided to leave my publishing company to go to university later on in life, it felt like something I had to do. When I ended my marriage, I felt I had no choice — but of course, in theory at least, I did.

More objectively, there is no doubt that we are profoundly affected by our genes and brain chemistry. We are created by our social and parental environment, shaped by the language we speak, and fashioned by the things that happen to us, accidentally or otherwise. Our character is subject to so many forces beyond our control. How can any choice, then, be said to be free?

It was only after I finished studying history (or to give it another name, ‘Western notions of cause-and-effect’) and began to study Zen Buddhism that some kind of meaningful answer began to occur to me. No one could resolve the question of free will versus determinism because, fundamentally, it was the wrong question. The real question was not: Do I have a choice? Rather it was: Who is the ‘me’ that’s asking if I have a choice?

If there is no ‘I’ to make a choice, then there is only one process going on — that of existence as a whole. No one — no fate, or brute circumstance — is pushing you around because there is no one to be pushed around. Or to put it another way, you are both simultaneously the one who is doing the pushing and the one who is being pushed. To think of this process in another way, consider your breathing: are ‘you’ breathing, or is breathing happening to you?

Of course, this is no simple solution. It merely shifts the focus and takes us on to another equally dense philosophical question: Who am I? Individuals in the West tend to consider themselves as a sort of ‘first cause’, an isolated ego that somehow acts on ‘the world out there’. We see ourselves as struggling against our external world, as that same world struggles to dominate us. And it feels, for some, like a fight to the death.

The view that there is no ‘you’ for things to happen to is a hard, even painful one to accept

But what if, for a moment, we entertain the possibility that there is no ‘me’. No ‘I’ who can act freely or be fated to become X or Y. What if, as Carl Jung suggested, the ego is simply a complex of the unconscious, a mere concept, and as such quite powerless? This might go against everything we have ever been taught, both overtly and subliminally, but to me, it seems and feels convincing. After all, can you show me your ego? Where is it? How can you be so certain that it exists? It’s not a tangible sensation, like ‘love’ or ‘fear’. Rather, it’s an idea that perhaps we don’t even realise is an idea, so much do we take it for granted. Maybe it’s just an abstraction — like the number three.

If you take this admittedly large leap – that there is no such thing as the you that ‘you’ imagine yourself to be – then what? Then ‘you’ at the deepest level are simply one particular expression of everything else that is going on. Or as the Zen writer Alan Watts put it: ‘Will and fate are two aspects of the same thing. Life lives you, you do not live life. Everything that happens is “of itself so”.’

What you do is what the whole universe is doing now. In the same way, a single wave is something the whole ocean is doing — you cannot point to a discrete end or beginning of a wave. You are experiencing different aspects of one thing happening, not separate events linked by cause and effect. Imagine a dance between two people that looks so seamless you can’t tell who’s leading and who’s following. Is it the ‘you’ who is called ‘Tim Lott’ or ‘Joe Doakes’ or whatever, or is it the sum total of everything that’s going on? Ultimately, what’s the difference?

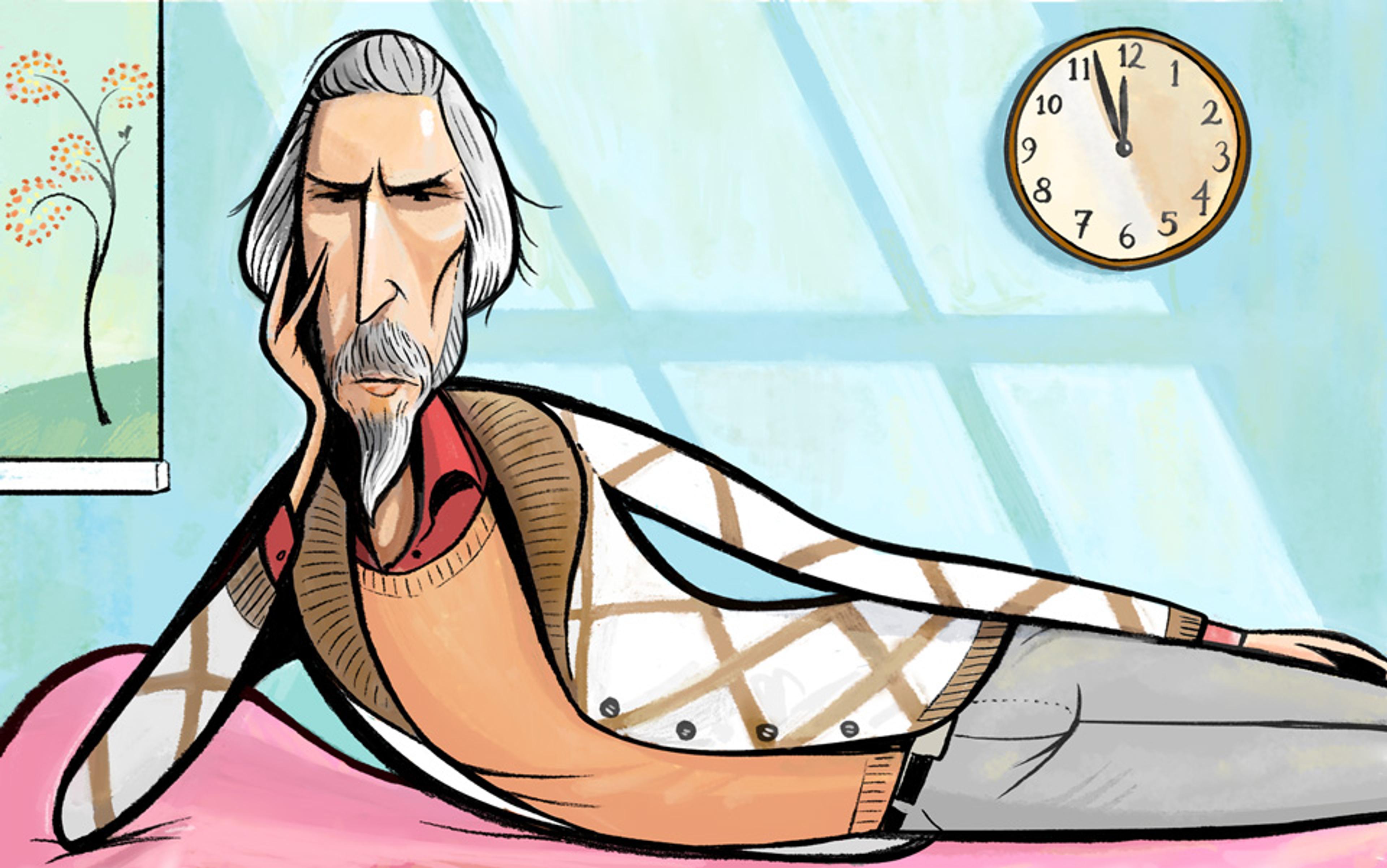

But where does this leave you? ‘Free’ to do whatever you want to do? Possibly. Or perhaps its means you’re absolutely unfree. It depends which way you look at it. The view that there is no ‘you’ for things to happen to is a hard, even painful one to accept. There is only a continuum: you, everything. There is no such thing as progression in time, with one cause pushing a certain effect. This is also an illusion.

For some this could be a terrifying prospect. But for me this is a good arrangement. It involves a universe full of surprises rather than a dead machine, as the determinists would have it. And neither is it a factory of regret, guilt and anxiety, which tend to be suffered by those who believe in free will too much. It leaves existence as a profound mystery and, without mystery, life would be intolerably boring.

Let your brain do the work without interference, just as you let your liver or your heart do their jobs

When I am faced with a difficult choice now, I neither make it nor don’t make it. As Zen teaching has it, I try to await the condition of being ‘choicelessly aware’. At some point, the choice ‘just happens’, in the same way that your breath ‘just happens’, when you’re not thinking about it. Let your brain do the work without interference, just as you let your liver or your heart do their jobs without interference. Don’t let your ego — your centre of conscious reflection — get in the way. In other words, you are trusting ‘nature’ — or if you prefer, your unconscious — to make the choice for you. Nature is not always to be trusted, but it is a better bet than so called ‘rational action’; it contains a wisdom that is far deeper than reason.

If you think too much about a choice, it is bound to go awry. The same instinct that governs, lightly, your decision whether or not to go out for a walk should be the same instinct that decides whether or not to stay in your marriage. It is not motivated action. It does not involve a cost-benefit analysis. It just recognises when, and if, the door of action is open, and suggests whether you might want to walk through it — or not. What happens next is not a matter of reason, but only of courage, and faith.