Consider the following developments in UK policy. Last year, Britain’s Office for National Statistics published its first ever set of ‘national well-being’ indicators, which were based on surveys of how satisfied people felt with their lives. Next year, it will be illegal to sell a bottle of wine in Scotland for less than £4.69. Meanwhile, in the face of prolonged economic stagnation, welfare claimants and young people are being urged or forced to work for free in order to develop the mindset and motivation to render them employable in the future.

None of these examples alone seems especially significant. Taking them together, however, we can begin to trace the outline of a subtly new way of conceiving of economic activity, one that is exerting a growing influence among policymakers in Britain. Crucially, for good and for ill, the authority of monetary prices as authoritative indicators of value is diminishing. Formerly, society’s progress was measured in terms of GDP, a bottle of wine was worth whatever the market would allow, and work was remunerated in wages. Now, the rise of psychological perspectives on the economy is providing a new framework. As the sciences of well-being and economic behaviour grow more sophisticated, the potential arises for a new way of understanding value. And as we witness this framework on the rise, so we might be witnessing the slow death of the paradigm known as neoliberalism.

In order to understand the significance of these seemingly low-level changes, we need to think back to the 1940s, when the economic power of central governments was growing at unprecedented speed. Centralised economic planning was at its height thanks to a combination of world war, statist ideologies and the new macroeconomic techniques invented by John Maynard Keynes. It was against this backdrop that a marginalised group of economists and philosophers began the neoliberal fightback. They were inspired and organised by the émigré Austrian intellectual, Friedrich Von Hayek.

Policymakers are recognising that there is a limit to how much consumer freedom we can cope with

Hayek argued, most notably in his 1944 classic The Road to Serfdom, that economic planning always led to tyranny — that was the inevitable result of allowing centralised experts to take unilateral decisions on behalf of the population. By contrast, the free market that had operated during the heyday of Victorian liberalism served as a mechanism for coordinating millions of decisions, with no single individual or institution dictating the ultimate outcome. By trusting individuals to pursue their own goals without consensus or debate, markets had an innately liberal quality, quite aside from whatever efficiency claims might also be made for them.

Markets, from this perspective, are information-processing machines. They are like vast computers, channelling decisions, desires and preferences. They have no ideas of their own about what is worth producing and having: they just process the choices that individuals happen to make. And their capacity to do this is all thanks to the price mechanism. Increased desire for some good or service will cause the price to rise, resulting in more of that good or service being offered. Hayek, supported by Milton Friedman and the Chicago School of economics, urged policymakers to abandon any concern with desirable economic outcomes or values. Instead, they should focus only on building the structures within which the price mechanism could operate freely. This is why, for example, neoliberals have long viewed cartel-busting as one of the state’s foremost responsibilities.

The prolonged economic slowdown of the 1970s created a thirst for new policy ideas, which the neoliberals cleverly satisfied. Although the purity of Hayek’s vision was inevitably polluted by the messy reality of politics, the new era that Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan ushered in treated free markets, governed by the magic of price, as the basis for the moral and economic logic of state and society. At the heart of the neoliberal era were two fundamental assumptions. Firstly, individuals, not experts, were the best judges of their own tastes and welfare. Secondly, the price mechanism of the market could be trusted to adjudicate between the various competing ideas, values and preferences that exist in modern societies. The state, by contrast, could not.

By this definition, a society in which it is illegal to sell a bottle of wine for £4.50, no matter how profitable it is to do so, nor how much demand there is for it, is no longer a neoliberal society. A different set of assumptions is built into such a policy. Unlike so-called ‘sin taxes’ that governments have long levied on tobacco and alcohol as a morally righteous way to increase their own revenue, a state-enforced price has no fiscal rationale, other than the longer-term reduction of health spending. Evidently, it is no longer assumed that individuals are necessarily the best judges of their own welfare. And although a price still exists, it is no longer set only by the magical forces of supply and demand. Expert decree now has a place. To put this another way, policymakers are recognising that there is a limit to how much consumer freedom we can cope with.

Minimum alcohol pricing would have appalled Hayek and his followers, just as maximum rental prices were an early target of Friedman’s criticisms. And yet it does not exactly mark a return to the planning of the 1940s, either. As so often happens during times of economic crisis, an entirely new logic is emerging on the back of neoliberalism. At the core of this logic is a new vision of the individual, who is acting partly in a calculating economic fashion, but partly in a social, habitual fashion. When the two come into conflict, as arguably occurred in the financial sector, the results can be disastrous.

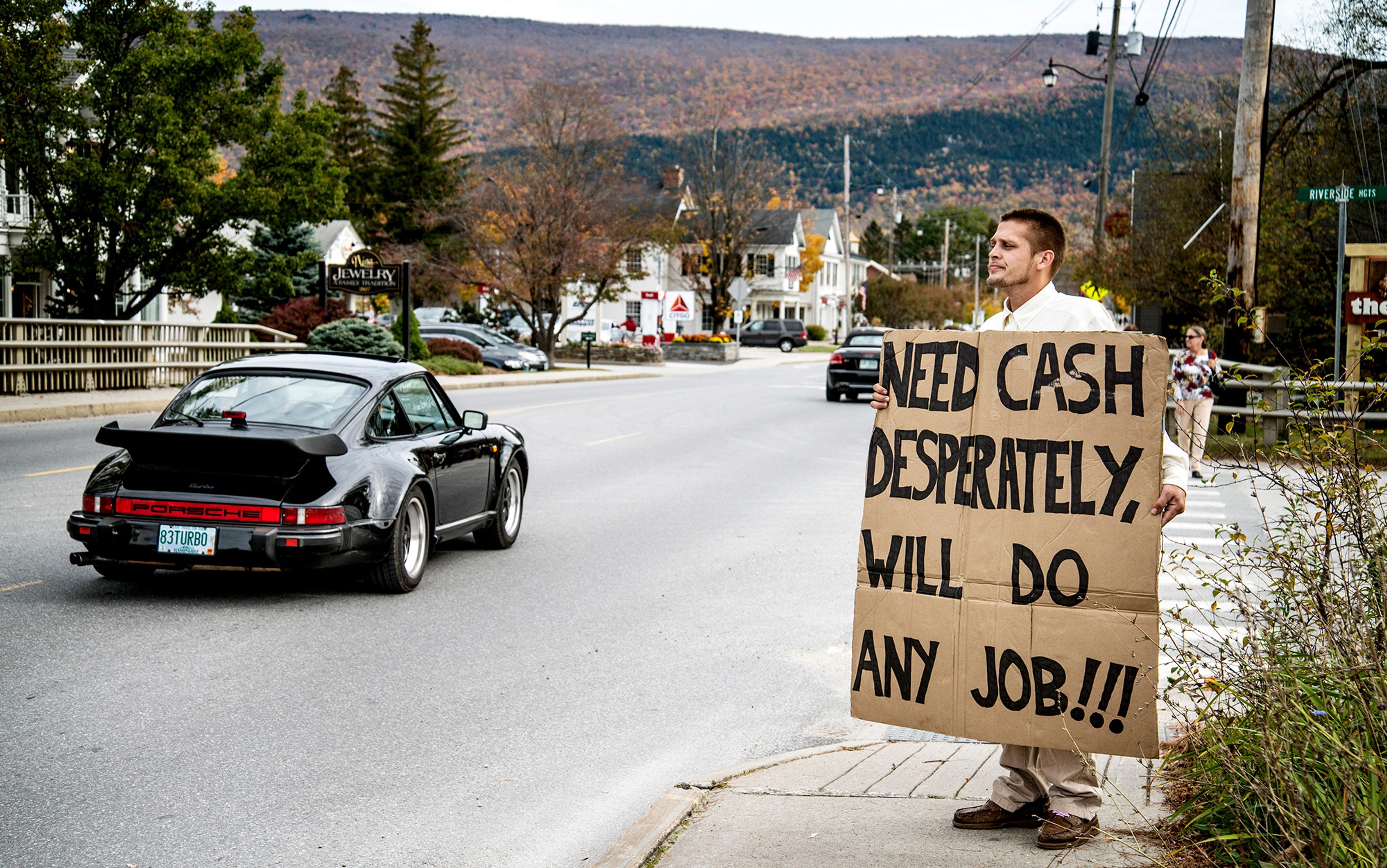

The implications for work are as significant as they are for consumption. One of the most striking findings from the new science of well-being (admittedly noticed by Sigmund Freud a century earlier) is that work is an indispensable condition of human happiness. This is something that economists believe they can now prove. Yet the discovery takes on an ambiguous cast in light of the return of high unemployment. Thanks to the new statistical data on happiness, ‘jobs’ and economic tasks can now be offered to those on the margins of society on the premise that work is psychologically valuable, regardless of whether it is remunerated. And so the institution of the labour market begins to look quite different.

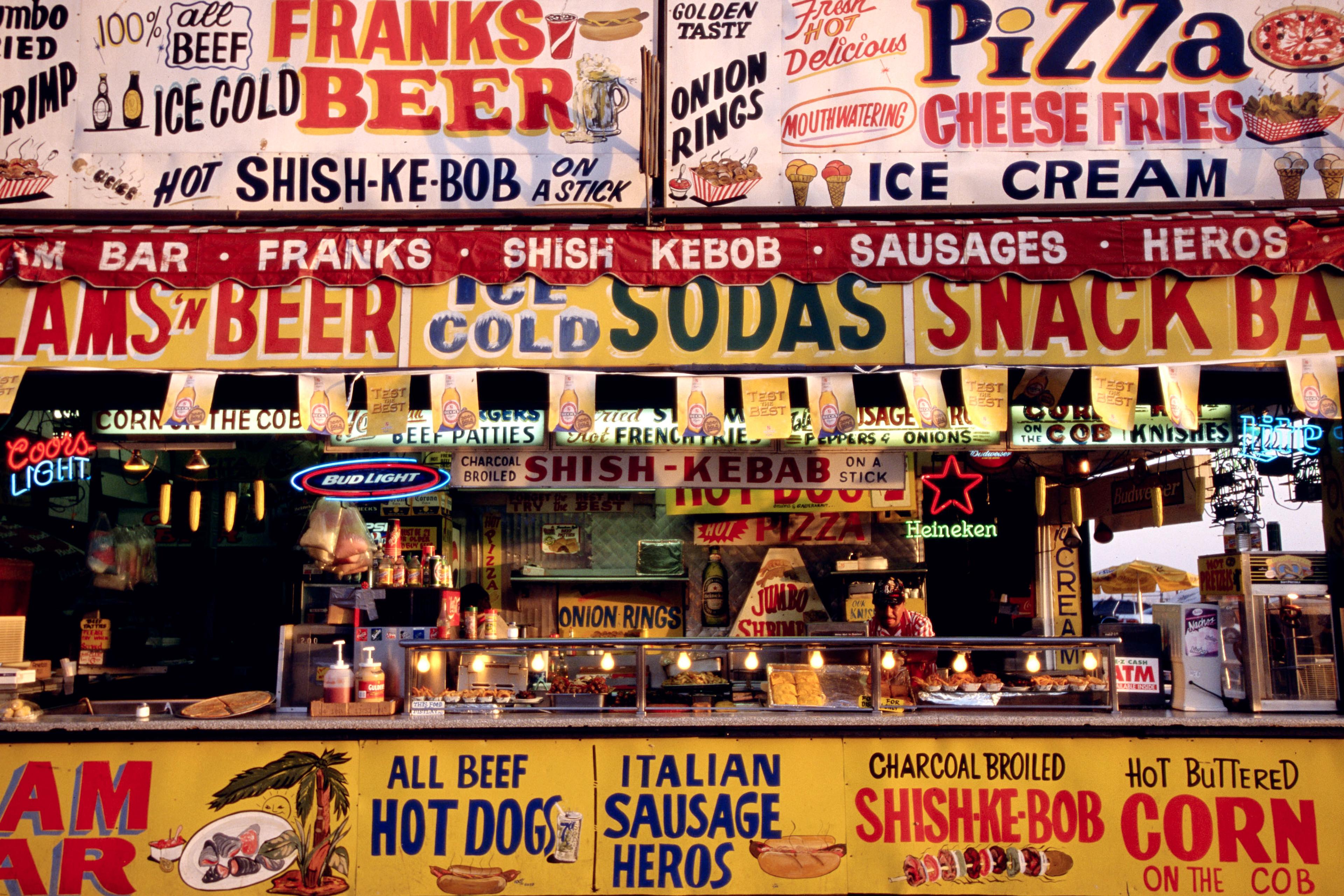

The disciplines of economics and psychology parted ways in the 1890s, the former operating on the methodological assumption that people would act rationally to satisfy themselves, the latter seeking to explore how people actually feel and behave using experiments and surveys. Yet the two have been growing closer since the early 1970s. The new fields of happiness economics and behavioural economics both offer more nuanced views of what happens when people make choices. Sometimes, it appears, they are influenced by other people in ways that traditional economics refuses to contemplate. Sometimes they do things that are repeatedly shown to make them worse-off in the long run. Such claims are scarcely novel in themselves; indeed, one might argue that they have been the fundamental premise of the marketing industry since the 1920s. Yet never before has this branch of economic psychology provided the logic for policy-making.

From this emerging ‘post-neoliberal’ perspective, individual choice and market prices are no longer altogether to be trusted. Especially where physical and mental health are concerned, there is a growing sense that experts need to teach individuals what is good for them in their day-to-day lives. Research into social networks suggests that ‘good’ and ‘bad’ habits are disseminated informally, meaning that policymakers now look for ways of influencing entire groups of people, rather than just isolated individuals. Neoliberalism applied the economic metaphor of ‘human capital’ to individuals. Now a new metaphor of behavioural ‘epidemics’ is used to understand how tastes and habits move through society.

If neoliberalism witnessed a market logic infiltrating ever more domains of state and society, this emerging policy paradigm sees a medical logic doing the same thing. Meanwhile, there is a trend for interpreting social, mental and behavioural problems in medical and physiological terms (a trend that neuroscience only exacerbates). Unless healthy behaviour can be promoted across the population, the strains on hospitals and doctors will become unmanageable. As a sign of things to come, responsibility for public health issues such as obesity and sexual health recently passed from the National Health Service to local government. All policies which are shown to reduce the economic burden on the NHS will get a hearing within this emerging, post-neoliberal policy paradigm.

It will take time for the ideology of ‘choice’ to diminish, especially as markets continue to penetrate our social and cultural lives. Neoliberal ideas moved from the intellectual margins of the 1940s into the policy mainstream of the 1970s and ’80s. They have finally arrived as a form of folk common sense for many people. We now assume that we have the right to lead whatever lifestyle we choose, according to our own tastes. But it is precisely because of this culture that governments are searching for justifications to set limits, to identify bad choices and promote well-being. The human mind, with all its self-destructive and herdlike tendencies, is now the territory into which economic policymakers are edging.