In the hospital with severe heart problems, Christian Roman had been told he was dying. Then in his mid-60s, the sometime teacher, travelling salesman, farmer and lawyer from the town of Sidney in Ohio was counting up his regrets from his hospital bed, and the one that gnawed at him the most was that he had done nothing to advance the cause of freethinking secularism. Fearing the damage that an open avowal of unbelief would do locally to his business and reputation, he had kept his irreligious views concealed for decades. With various ministers visiting him uninvited in his infirmity – there were 17 churches in town, and Roman cared for none of them – he decided that he would commission a glorious cemetery monument through which he would finally ‘speak my mind without reservation’.

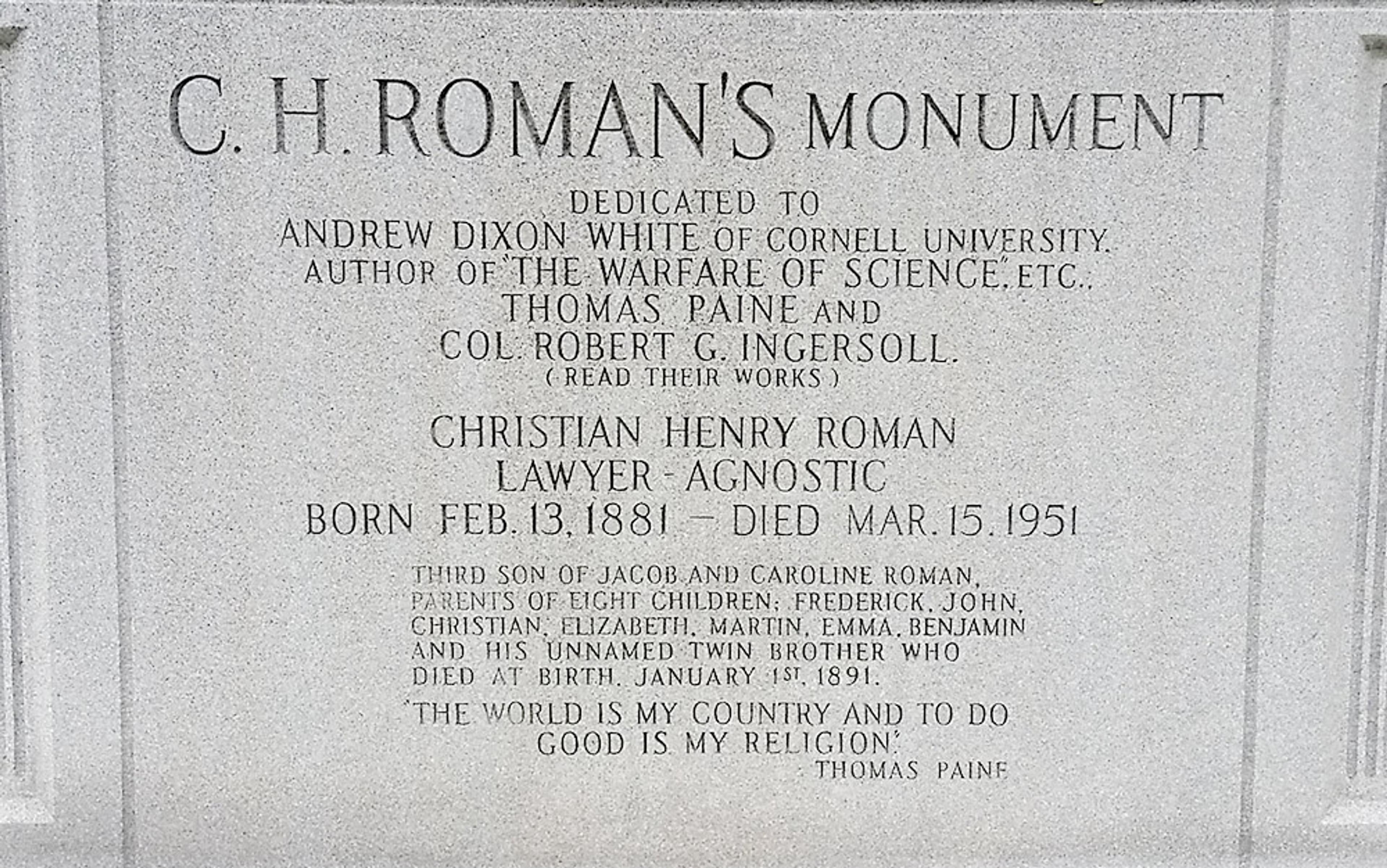

Roman’s heart did not fail him this time (it would a few years later, in 1951). Still, he wanted to make good on his hospital pledge, and saw no need now to wait for a posthumous testimonial. Why not proactively erect his ‘Agnostic Monument’ in Graceland Cemetery for all to see ‘regardless of public censure’? Investing much of his savings in the project, he wanted it to be the largest monument in the Sidney graveyard, and he pulled off the installation in August 1948. The result was imposing: a giant granite block heralding the freethinking triumvirate of the deistic revolutionary Thomas Paine, the infidel orator Robert Ingersoll, and the Cornell president Andrew Dickson White. ‘READ THEIR WORKS,’ the megalith advised. An anti-sermon in stone, Roman’s monument declared science the ‘SOLE REVELATION’, and repeated Ingersoll’s freethinking thoughts on death and immortality. Also, as his beloved Ingersoll was wont to do, Roman slipped in some bourgeois moralising with his irreligious polemic: ‘EVILS OF MY DAY; USE OF TOBACCO, ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGES AND RELIGIOUS SUPERSTITION.’ He wanted his neighbours to know that he could be good – and just as abstemious as a Methodist teetotaller – without God.

Detail of the inscription upon the tombstone of Christian Roman in Sidney, Ohio. Photo courtesy the author.

The monument certainly got the community talking, attracting ‘a constant stream’ of curious visitors to ponder its bold message. The pastor of the First Presbyterian Church, John W Meister, devoted a whole sermon to the subject of ‘Christian Roman’s Tombstone’, which conjured to him a spectre of infidelity weirdly out of place amid the United States’ postwar religious upswing. ‘I never seriously thought that in my generation there would be cause for argument with a real, live agnostic,’ Meister preached to a crowded congregation. After two world wars and the Great Depression, humanistic self-regard paled before the sterner stuff of neo-orthodox faith and, with the dawning of the Cold War, there was little room for doubting God, Jesus and the Bible without seeming to underwrite Soviet communism and atheism.

Meister framed the offence, ‘if not insult’, of Roman’s monument in sophisticated theological and historical terms. ‘Let the church never substitute dogma for intellect; let us never laugh off a questioning mind,’ the pastor advised those Christians who were ‘up in arms’ over Roman’s gravestone. The nuance of Meister’s criticism was lost at least on some in town, particularly on those who talked glibly about ‘dynamiting it’ right out of the cemetery. ‘For Shame,’ scrawled a vandal across the base of the marker. The indignation was still fresh enough two years later that Edwin H Wilson, a national emissary for the American Humanist Association, called off a public dedication of the monument, much to Roman’s chagrin.

Roman’s desire to materialise his unbelief, to create a monument to secularism in a bucolic Ohio graveyard, was eccentric, but not – as it turns out – that eccentric. American freethinkers had long been preoccupied with the public memorialising of their incredulity and anticlericalism. They wanted to enshrine their commitment to scientific rationality over biblical revelation, their strict construction of church-state separation, and their worldly focus on human happiness in the here and now. They wanted their humanistic beliefs recognised in a nation that routinely pictured itself in godly, covenantal and Christian terms. They wanted their secularism to be visible, out in the open rather than closeted away, celebrated rather than hidden. They wanted to render a secular public sphere tangible, to give it corporeality and granite-like solidity, so they strove to erect monuments, memorials and museums. The commemorative landscape they hoped to enter was crowded, of course – with assorted tributes to the battles of the American Revolution, with Union shrines honouring Abraham Lincoln, with statues hallowing the Confederacy’s Lost Cause, with Bible institutes named for famous evangelists, with pilgrimage sites associated with Catholic saints, with Halls of Fame for every conceivable sport. Freethinkers wanted visibility in the packed US topography of memory.

As with so many things that the outnumbered secularists of the US have tried to do, there was often a forlorn quality to their endeavours to concretise their irreligion. ‘The thought tides are in the direction of God,’ the Rev Meister was certain as he surveyed the religious landscape of the late 1940s, so much so that he found it easy to cast Roman’s tombstone into the oblivion of the readily forgotten. ‘That monument, pretentious as it is,’ Meister averred, ‘will be mouldering dust when the [word] of Jesus will still be drawing men unto God.’ In the US, the promise of secularism always seemed to founder on the nation’s next revival, awakening or crusade – on religion’s inevitable return, on Christianity’s inescapable presence and power. That did not keep US freethinkers from their building projects. The majoritarian odds against them made them only surer of the importance of materialising their politics and their doubts.

For freethinkers, the notion that temples of reason should replace churches was more than a figurative expression of science’s supplanting of Christianity. The Enlightenment would require its own calendar of festivals and rites, its own pantheon of saints and apotheosised heroes, its own monuments and shrines. That was nowhere more grandly apparent than at the height of the French Revolution when Notre Dame was transformed from a Catholic cathedral to a secular altar for a festival of reason and liberty.

It was never enough for philosophes to dethrone Christianity; a positive civic faith had to supersede churches, sacraments and Sabbaths. A new age of reason, science, liberty and democratic citizenship would need its own religion of humanity – that proposition absorbed any number of 19th-century expositors, from the French positivist Auguste Comte and the English theorist John Stuart Mill to the US radical Octavius Frothingham. Freethinkers recognised the functionality of rites, ceremonies and monuments for the upholding of free enquiry, philanthropic benevolence, scientific knowledge and social solidarity. They saw, too, the importance of ritual for solemnising important life passages. Without Christianity or Judaism to guide them, they had to become their own liturgists. Hence the leading US freethought publisher, D M Bennett, issued ‘for the use of liberals’, the Truth Seeker Collection of Forms, Hymns, and Recitations (1877), a compendium of secular rites for public meetings, weddings, commemorations and funerals. Among the prescribed invocations was this one torn from the annals of the radical Enlightenment: ‘May churches and chapels be converted into Temples of Reason and Secular Institutions for the people.’

No one exerted a more lasting influence on the ritual life of US freethinkers than Paine, whose Age of Reason (1794-1807) attacking the Bible became the holy writ of 19th-century unbelief. It was no surprise that Roman had inscribed a familiar scrap of Paine’s cosmopolitan sentiments on the face of his monument: ‘The world is my country and to do good is my religion.’ By the 1830s, the resident deists of the US had already turned Paine’s birthday into their favourite annual festival, an occasion for banquets, odes, toasts and orations – all dedicated to honouring Paine’s contributions to forwarding religious and political liberty. In Bennett’s ritual guide, George Washington and Thomas Jefferson shared a single toast with Paine as co-labourers in the cause of freedom; Benjamin Franklin and James Madison got nary a mention. ‘Immortal Paine,’ by contrast, was everywhere. ‘Hail! the auspicious day/ Hail, hail the natal day/ Of Thomas Paine,’ opened one birthday hymn. ‘May he yet be placed upon a pedestal as high as ever erected to the memory of man,’ a sample tribute proclaimed, ‘and may each returning anniversary witness the extension of the principles for which he contended, until the ‘Rights of Man’ shall be universally admitted, an ‘Age of Reason’ triumph over superstition, and priestcraft and kingcraft shall be known no more.’

The pedestal was, again, a lot more than a metaphor. As early as 1839, the freethinker Gilbert Vale had led efforts to commemorate Paine with a monument in New Rochelle in New York State, where Paine had lived for a time after his return to the US in 1802. The growing fervour of Paine’s evangelical critics had engendered a rude welcome for the old patriot, but those punishing attacks made his admirers only more committed to burnishing his reputation after his death. The solicitous upkeep of Paine’s memorial in New Rochelle became part of the shared work of US secularists. Over the course of the century, they preserved it from vandals and souvenir-seekers, raised money to refurbish and rededicate it, and made pilgrimages there for picnics and processions. Finally, in 1899, they managed to add a ‘colossal bronze bust’ atop Vale’s original marble column.

All these commemorative efforts had grown into a full-fledged museum by 1910, thanks especially to the roving freethinker Moncure Conway, whose collecting efforts spanned the Atlantic. At the time of the museum’s opening, The New York Times reported that among the relics amassed was a life-size wax figure of Paine, a lock of his hair, and even a portion of his brain. A decade after Paine’s death, a British admirer had stolen the pamphleteer’s remains from New Rochelle in order to repatriate them back in England, only to have the skeleton go missing. Conway tried to relocate and reclaim Paine’s bones without success, but the artefacts he did secure for the Paine Historical Association certainly made plain the relic-hunting corporeality of secularist memory.

Bruno’s murder would not be avenged until a monument was raised for him upon ‘the shapeless ruin of St Peter’s’

Paine got most of the attention among US freethinkers as a founding father, but they were willing to push their calendar back for the heretic Giordano Bruno, burned at the stake in Rome by the Inquisition in 1600. Following the lead of historians such as Cornell’s Dickson White, one of the three guides whom Roman enshrined on his monument, liberal secularists saw a protracted war between science and religion as pivotal to the making of modernity. From Copernicus and Galileo to Charles Darwin, Christianity was viewed as having continually tried to suppress new knowledge: Bruno, a dissident Italian cosmologist, was transformed into a martyr for free enquiry, a condensed symbol of the murderous violence and dark anti-intellectualism of the church against which modern science had courageously struggled. Thaddeus B Wakeman, a Manhattan lawyer who sparred with the infamous vice crusader Anthony Comstock, was so taken with the heretic’s emblematic power that he suggested re-centring the entire calendar away from the birth of Christ to the death of Bruno. Time, he pronounced in 1881, properly began with Bruno’s sacrifice in 1600, and a congress of freethinkers meeting the next year in St Louis heartily endorsed the proposal. The year 1882 became 282, and many US freethinkers, for a decade and more thereafter, relished flaunting the revised dating system in their correspondence, journals and tracts as a tell-tale sign of their emancipation from Christianity.

The veneration of Bruno peaked on 9 June 1889 with the grand unveiling of a statue in his honour in the very square in Rome where he had been executed. Unlike most of the memorial efforts in which US secularists participated, the Bruno monument was a global endeavour involving anticlerical, freethinking subscribers from Australia to Italy. More than 30,000 people gathered for the event – a striking show of liberal solidarity in the very face of Catholic authority. With characteristic oratorical flourish, Ingersoll had called Bruno ‘the first real martyr’, an ‘atheist’ who had died ‘neither frightened by perdition, nor bribed by heaven’, whose murder would not be ‘perfectly avenged’ until a monument was raised for him upon ‘the shapeless ruin of St Peter’s, the crumbled Vatican and the fallen cross’.

By those standards, the redress freethinkers gained in 1889 was far from perfect. Pope Leo XIII, with the Vatican very much intact, excoriated Bruno anew as a deceitful apostate, decried the abomination of the holy city, and urged Catholics to keep fighting the infidelity of radical republicanism. That papal response hardly lessened the pride and satisfaction of freethinkers: they had bearded the lion in his own den and set up a monument to the ‘Herald of the Dawn’. The editor H L Green of Buffalo was so pleased with the news of the statue’s dedication that he created a commemorative volume highlighting all the work that went into making that festive day possible, including a list of each gift – large and small, by name – that Americans had made in service of this secular pageantry.

The Bruno spectacle was a ceremonial high point for 19th-century secularists. No other commemoration could match the Eternal City as a staging ground for contesting religious authority and sanctifying free enquiry. Most freethinking monuments were necessarily more modest affairs, more Roman’s Graceland Cemetery than Rome’s Campo de’ Fiori. When, for example, Bennett died in 1882, he was eulogised as a giant among US freethinkers, a valiant champion of a free press who had spent 13 months in a New York prison for his blasphemous publications. His admirers immediately established a monument committee, and secularists from around the country contributed their mite. The result was a wordy memorial in a Brooklyn cemetery, dedicated with pomp and ceremony in June 1884. Bennett’s irreligious enthusiasts pulled no punches in their engraved homage: ‘What is called revelation is a snare, a delusion, a falsehood,’ one side of the monument read. ‘Those who claim to speak for the gods simply speak their own thought. The gods do not speak; they are as dumb as the rocks.’

Likewise, when Katie Kehm Smith, the charismatic founder of the First Secular Church of Portland, died young out on the lecture circuit in eastern Oregon in 1895, her supporters instinctively established a monument fund. Three years later, they journeyed to the remote graveyard in the Haystack Valley where Smith had been buried to unveil a marble obelisk to ‘a woman without superstition’. On one side, it was engraved with a secularist badge, a torch of reason representing the light of science, and on another, it echoed the same line from Paine that Roman would later choose: ‘The world is my country. To do good is my religion.’ Thus did Oregon’s freethinkers devotedly chisel their cosmopolitan humanism into a tiny hillside cemetery a long way from Portland, let alone London, New York or Paris.

The considerable labours of 19th-century freethinkers to materialise secularism carried forward into the next century. Memorial projects for Ingersoll, the most celebrated US freethinker, who died in 1899, were particularly consuming to his 20th-century heirs. One focal point was the erection in 1911 of a lofty statue of him in a municipal park in the city of Peoria in Illinois, which became – like the Paine monument in New Rochelle – a ritual hub for humanists and atheists. From a centennial celebration of Ingersoll’s birth in 1933 to a rededication ceremony in August 2016 led by the Freedom from Religion Foundation, US nonbelievers have maintained the Peoria bronze with reverential affection, and used it as a public stage for dramatising their own secularist commitments.

Ingersoll speaking in New Rochelle, New York, 30 May 1894. Courtesy of the Robert Green Ingersoll Birthplace Museum.

The Philadelphia-based sculptor Zenos Frudakis, who oversaw the recent restoration of the 105-year-old statue, viewed the labour as an expression of his own humanistic credo and as a counterpoint to the evangelical Right. ‘Rational thinking’ of the sort that Ingersoll embodied, Frudakis suggests, is in short supply in a country where science-denying Christians hold all too much sway. The statue, refurbished for the next century, stands for Frudakis and company as a reminder of a necessary secularist alternative.

Peoria could claim Ingersoll as a long-time citizen, but his actual birthplace was Dresden in New York state. By 1921, freethinkers had opened a museum there in what had been the Presbyterian parsonage of Ingersoll’s father. Still open for tours, it is a shrine of Ingersoll memorabilia – photographs, plaques and posters, but also a silver spoon produced by an atheist jeweller with the great agnostic’s likeness on the stem, as well as an oversize bust rescued from the demolition of freethinker Philo D Beckwith’s Victorian theatre in the Michigan city of Dowagiac. Announcing an illustrious past, the Ingersoll Birthplace Museum – a modest house in a small town in the Finger Lakes – testifies to the limits of secularism’s reach and the spindly hold that the heroes of freethought have on the nation’s historical imagination: ‘Meet the most remarkable American most people never heard of,’ the museum beckons visitors. It was a sentiment of lost renown that echoed in the Peoria ceremony the summer before last: Ingersoll is ‘the most famous Peorian you’ve never heard of’, as a local humanist told a reporter covering the event. Like Roman’s ‘Agnostic Monument’, the Ingersoll tributes of Dresden and Peoria stand as minority reports of infidelity in God’s country.

Ingersoll’s Birthplace Museum might have a quixotic air, but it seems an endeavour of restrained practicality by comparison with the founding of the American Atheist Museum in Petersburg, Indiana. Opened on the summer solstice in June 1978 with the notorious atheist Madalyn Murray O’Hair on hand for the ribbon-cutting, the museum was the brainchild of Lloyd and Pam Thoren, both extremely lapsed Protestants. Part of a loose network of atheist activists whom O’Hair had organised from her base in Austin, Texas, the Thorens decided that the best way that they could help the cause was to construct a godless exhibition on their rural property in a ‘small, religious community in the Bible Belt of the Midwest’. With O’Hair’s encouragement, the Thorens had an eye on the publicity possibilities of provoking Christian opposition and having the national media play up the controversy.

An atheist museum – surely, that belonged behind the Iron Curtain, not in the US heartland

The calculation worked. A United Press International story, quickly wired across the country, quoted a pastor of a local Bible church who saw the new atheist museum in town as a sign of the last days, and who repeated rumours about animal sacrifice and devil worship. Even when reporters did not resort to fundamentalist stereotypes, they found it hard to resist chronicling just how religiously out of place ‘the only atheist museum in the Western Hemisphere’ appeared. Not far away, a journalist for The Indianapolis Star noted, was a monument to major-league baseball player Gil Hodges, a beloved Hoosier and himself a graduate of Petersburg High School. ‘Above all [Hodges] was dedicated to God, family, country and the game of baseball,’ his monument read. An atheist museum – surely, that belonged behind the Iron Curtain, not in the US heartland.

To the Thorens, of course, the whole point was to materialise a secularist alternative to a nation resolutely under God. ‘In Reason We Trust’ and ‘Born Again Atheist’ announced a pair of buttons available in the museum’s gift shop. The homemade exhibits – paeans to Darwinian evolution and the naturalistic study of religion – were the murals of grassroots atheism. The Thorens had even hauled in old church pews, so that visitors could sit down and contemplate everything from the Big Bang and the dangers of Christian indoctrination to a pioneer’s log cabin. ‘A mentally tidy visitor,’ one reporter observed, might have trouble knowing ‘the proper cerebral slot’ in which to file away many of the items on display. The museum, after all, sat in the shadow of a five-story wood tower that the couple had built as an enormous birdhouse in hopes of attracting purple martins.

Taken altogether, the compound represented the vernacular art of US atheism, a quirky pastiche of material secularism set against the head winds of the Cold War and an awakened evangelical conservatism. ‘Most of the people around here wish we would pack up and leave,’ Lloyd told a reporter for The Los Angeles Times two-plus years into operating the museum. ‘But Pam and I have as much right to be here and express our views as anyone else.’ The Thorens carried on in their curatorial capacity for six more years but finally decided that they needed the anonymity of a big city, especially for their young daughter. When they left for San Francisco in 1987, they removed all but four letters from the large yellow rooftop sign announcing the American Atheist Museum. ‘MUSE’ was the remnant of their Indiana monument to unbelief.

Materialising secularism, giving it ritual shape and monumental expression, has picked up again as the ‘new atheists’ – Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris, and company – have become bestsellers, and as the number of Americans claiming no religious affiliation has grown dramatically in the past decade and a half. Defenders of scientific rationality and free enquiry have mounted new festivals such as International Darwin Day on February 12 and International Blasphemy Rights Day on September 30 to keep up the battle against superstition. This past summer, the Freedom from Religion Foundation orchestrated the dedication of a seven-foot-tall bronze statue of Clarence Darrow in Dayton, Tennessee, the site of the infamous Scopes Monkey Trial in 1925. (His anti-evolution opponent, William Jennings Bryan, had already been memorialised some years earlier with a statue outside the courthouse, but now Bryan’s likeness – thanks once more to Frudakis the sculptor – must share public space again with his infidel adversary.)

Atheists and nonbelievers have also launched new congregational ventures – most prominently, the Sunday Assembly and Oasis – in several cities across the country, and humanist chaplaincies have flowered on a number of college campuses to afford a community for openly secular students. The UK-based philosopher Alain de Botton has crystallised much of this recent ritual creativity in Religion for Atheists (2012), in which he expressly reimagines Comte’s religion of humanity for contemporary nonbelievers. Restaurants and art museums, de Botton suggests, are potential sites for humanistic liturgies of communal solidarity and unbuttoned conviviality. Whether in Sunday gatherings or funeral rites, the new secularists court temple, sacrament and monument much as the old secularists long did.

Perhaps the most successful instance of that courtship has been the Satanic Temple – a group of freethinking activists, led by the pseudonymous Lucien Greaves, which has puckishly deployed an occult statue of Baphomet to challenge a monument devoted to the Ten Commandments at the State Capitol in Oklahoma. Winning its case before the Oklahoma Supreme Court in 2015, the troupe forced state officials into the bind of removing the Decalogue or having it share space with a winged, goat-headed, pagan idol – a topsy-turvy symbol to these ‘Satanists’ of equal liberty, rational enquiry and free expression. Reluctantly, the state’s Republican leadership decided that it was better to take down the Ten Commandments than to make room for such sacrilege. Deprived of a space in Oklahoma’s public square, the statue of Baphomet went instead to Michigan where it has been installed as the showpiece of Detroit’s chapter of the Satanic Temple, the latest US monument to blasphemy, infidelity and strict church-state separation.

So it is that Baphomet, ‘the heretic who questions sacred laws and rejects all tyrannical impositions’, now stands in for Paine, Bruno and Ingersoll. However fancifully, the monumental gestures of the Satanic Temple pay homage to ideals that the freethinkers of the US have long sought to enshrine: intellectual freedom, the value and reliability of scientific knowledge, the equal rights and liberties of nonbelievers, and the humanistic commitment to justice for all. In such times – when white evangelicals gave the world Donald Trump – the God of the US might well deserve anew the irreverence of Paine, Ingersoll, Darrow and Roman. The architects of the Satanic Temple, Greaves and company are among the latest bearers of that humanistic, freethinking impertinence.