Go to Campo dei Fiori in Rome on 17 February and you will find yourself surrounded by a motley crowd of atheists, pantheists, anarchists, Masons, mystics, Christian reformers and members of the Italian Association of Free Thinkers, all rubbing shoulders with an official delegation from City Hall.

Every year, this unlikely congregation gathers to lay wreaths at the foot of the 19th-century statue that glowers over the piazza from beneath its friar’s cowl; flowers, candles, poems and tributes pile up against the plinth whose inscription reads: ‘To Bruno, from the generation he foresaw, here, where the pyre burned.’ In the four centuries since he was executed for heresy by the Roman Inquisition, this diminutive iconoclast has been appropriated as a symbol by all manner of causes, reflecting the complexities and contradictions inherent in his ideas, his writings and his character.

Giordano Bruno was born in Nola, at the foot of Mount Vesuvius, in 1548, a soldier’s son who joined the prestigious Dominican convent of San Domenico Maggiore in nearby Naples at the age of 17. He excelled in philosophy and theology, but his precocious intellect proved as much a liability as an asset; he was constantly in trouble with his superiors for questioning orthodoxies and seeking out forbidden reading material.

In 1576, he was forced to flee the convent under the cover of darkness to avoid an interrogation by the local Inquisitor after being discovered reading Erasmus in the privy (he had thrown the book down the hole to hide the evidence, but someone was determined enough to fish it out).

So began an itinerant life that saw Bruno progress north through Italy to France, transforming himself along the way from defrocked friar (he was excommunicated in absentia for his unauthorised flight), to university teacher, to personal tutor to King Henry III of France, all in little more than five years.

This remarkable rise illustrates Bruno’s audacity and charisma but, although he began to move in influential circles, gaining a reputation for his prodigious memory and the artificial memory system he devised, his position always remained precarious; he made enemies with as much alacrity as he attracted admirers, and was thrown into prison in more than one city for giving offence in his public lectures. He published books that further consolidated his notoriety as a dangerous thinker.

Bruno moved from Paris to London, back to Paris, then on to Wittenburg, Prague, Zurich, Frankfurt, Padua and Venice, charming his way into the service of ambassadors, archdukes, kings and emperors, always seeking the sympathetic patron who would allow him to develop his philosophy without fear of reprisals from the authorities, but eventually his luck ran out. In Venice, he was betrayed and arrested by the Inquisition. After eight years in prison and two lengthy trials, he was led out to Campo dei Fiori on the morning of 17 February 1600, where he was burned alive, reportedly turning his face from the proffered crucifix in his final moments.

The German Catholic convert Gaspar Schoppe, who witnessed Bruno’s final trial and his execution, wrote an account afterwards to a friend in which he reported that, after the death sentence was pronounced: ‘He made no other reply than, in a menacing tone, [to say], “You may be more afraid to bring that sentence against me than I am to accept it.”’

The length of Bruno’s imprisonment and trials suggests an unease on the part of the Holy Office, a recognition that the case against him was far from clear-cut. Bruno’s defiance and integrity in refusing to recant have lent an air of martyrdom to his death – something he might even have sensed at the time, to judge by his response. But the nature of that martyrdom – if such it was – is less easy to pin down.

In 2014, Bruno found an unexpected cheerleader in the Fox TV series Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey, created as a follow-on from Carl Sagan’s 1980 documentaries. The first episode, broadcast simultaneously on Fox channels around the world with an introduction by President Barack Obama, saw the astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson presenting an animated (and vastly simplified) version of Bruno’s life that repeats a claim often made for him in recent years: that he was the first martyr for modern science.

In her book Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition (1964), Dame Frances Yates, one of the 20th century’s foremost English-language Bruno scholars, wrote:

Bruno is chiefly celebrated in histories of thought and of science, not only for his acceptance of the Copernican theory, but still more for his wonderful leap of the imagination by which he attached the idea of the infinity of the Universe to his Copernicanism, an extension of the theory which had not been taught by Copernicus himself.

It is often supposed that his sentence for heresy was principally due to his refusal to recant his belief in the infinity of the Universe, the possibility of multiple, inhabited worlds, and the Copernican heliocentric model of the cosmos. In fact, the Church had no official position on the Copernican system in 1600, when Bruno’s final trial was concluded; it was not until 16 years later that the Inquisition ruled it ‘formally heretical’ after Galileo’s writings on the subject were brought to their attention. Galileo was ordered to abandon his heliocentric theories, and to abstain from teaching, discussing or writing about them, by Cardinal Robert Bellarmine, the Jesuit Inquisitor who had also interrogated Bruno and sentenced him; it seems clear that Bellarmine still feared the implications and consequences of the new cosmology that Bruno had proclaimed.

We don’t know on precisely what grounds Bruno was condemned to death. The surviving decree of his sentence mentions eight separate charges of heresy, which he refused to abjure, but the detailed records of his Roman trials were lost when Napoleon Bonaparte ransacked the Vatican archive and moved part of it to Paris, so the specifics must be inferred from those papers that remain. From these, it appears that his cosmology was only a small part of his catalogue of offences against the Catholic Church.

‘his contributions to science are questionable. He was more belligerent free-thinker than proto-scientist’

In fact, Bruno’s scientific hypotheses were sketchy at best, based more on intuition than accurate mathematics, and he was as interested in ancient magic as he was in observational astronomy (a fact quietly airbrushed from his potted biography in Cosmos). Yates’s readings of Bruno emphasise his place in the history of Renaissance occult thought as part of a tradition stretching from Ramon Llull (whose art of memory Bruno built on) to the Rosicrucians and beyond, and her influence contributed to the prevailing view of him as a magus and Hermetist in late-20th-century scholarship.

More recent studies have tilted the balance back towards Bruno’s role in the development of scientific thought, though Brian Cox, who also recounts Bruno’s ‘cinematic death’ in the first chapter of his bestseller Human Universe (2014), is obliged to concede that ‘his contributions to science are questionable. He was more belligerent free-thinker than proto-scientist.’

Separating the historical Bruno from the subsequent appropriations of his life and work is complicated, therefore – though perhaps not as complicated as trying to answer the question of what he actually believed. He was a prolific writer who produced comic plays and philosophical dialogues in vernacular Italian, and epic poems and mathematical treatises in Latin.

‘The sheer variety of Giordano Bruno’s writings shows how difficult he found it to convey his ideas about the Universe,’ writes his most recent English-language biographer, Ingrid D Rowland in Giordano Bruno: Philosopher/Heretic (2008). On the title page of his early verse-drama The Candlemaker (1582), he calls himself ‘Bruno the Nolan, the Academic of No Academy, nicknamed The Exasperated’. Throughout his life of exile, he retained a nostalgic loyalty to his hometown, referring to his alter-ego in his books as ‘the Nolan’ and the particular worldview he cultivated and refined throughout his writing life as ‘the Nolan philosophy’.

Quite what that philosophy amounts to is not easily summarised, though we know from his writings, among them The Ash Wednesday Supper (1584) and On the Immense and Numberless (1591), that his theory of the infinite Universe was inspired by Copernicus and Nicholas of Cusa, whose ideas, he felt, did not go far enough. He believed unequivocally in the place of learned magic in philosophy; he posited in his work On the Triple Minimum (1591) that the universe was composed of tiny particles, which he called ‘atoms’; he understood the divinity as a benign animating force found not somewhere out beyond an arbitrary sphere of fixed stars, but in every component of the infinite Universe:

Principle of existence, wellspring of every species,

Mind, God, Being, One, Truth, Destiny, Reason.

This view of God necessarily had implications for his understanding of the nature of the Trinity and the divinity of Christ, one of the heretical positions he was called upon to defend to the Venetian Inquisition in his first trial:

I have, in effect, harboured doubts about the term [‘person’] for the Son and Holy Spirit, as I have never understood them as persons distinct from the Father…

If Bruno’s disparate writings don’t quite cohere into a comprehensive whole, we can still glimpse in them seeds of ideas that have been built on by later thinkers. But the Nolan philosophy was essentially a unifying, tolerant worldview, and Bruno nurtured a grand vision for it: he believed that his theories of the unity of God and the Universe, which transcended the arbitrary divisions of Catholic and Protestant, might be the key to solving the religious conflicts currently tearing Europe apart – if he could only find a temporal ruler willing to understand and champion his views.

Even from his final prison cell, Bruno was still desperately trying to get his writings into the Pope’s hands

At various times, through book dedications and lavish praise in his works, Bruno attempted to flatter Henry III of France, Elizabeth I of England and the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II into assuming that role but, although he received limited patronage, none of them lived up to his expectations. Eventually, with characteristic self-belief, it seems he intended to take his ideas to the very top.

When Bruno first returned to Italy in 1591, against all the advice of his friends, he contacted a Dominican of his acquaintance in Venice and told the friar that he was preparing a book to be presented to the new Pope, Clement VIII. For an excommunicated exile already of interest to the Inquisition to believe that he could persuade the supreme head of the Catholic Church to revise his entire theology might seem like presumption verging on lunacy, but Bruno seems to have possessed a breathtaking confidence in his own ideas that was frequently interpreted as arrogance by those around him. Yates even implied it might have been a kind of mania: ‘People like Giordano Bruno are immunised from a sense of danger by their sense of mission, or their megalomania, or the state of euphoria bordering on insanity in which they constantly live.’

But Bruno had some grounds for hoping he might engage the Pope’s interest; Clement was widely regarded as more liberal than his predecessors, and in the same year a fellow Italian Hermetist, Francesco Patrizi, had dedicated a book on Hermetic religious philosophy to the Pope and been rewarded with a Chair at the University of Rome.

Perhaps this lost book might have provided a definitive, syncretised account of the Nolan philosophy, but Bruno never got the chance to finish it; he was denounced to the Venetian Inquisition by the nobleman who had invited him back with the offer of patronage. Even from his final prison cell, he was still desperately trying to get his writings into the Pope’s hands; the transcript of his sentence reports that, rather than agree to recant his heresies before the Inquisitors, ‘you presented a document addressed to His Holiness and to us, which, as you said, concerned your defence’. Even if Clement read it, which seems unlikely, it was too late to do Bruno any good.

I’ve been fascinated by Bruno’s life and ideas for 20 years, though I am not a Bruno scholar. As a novelist, I have always been more intrigued by the drama of his life and the contradictions of his character than by the minutiae of his philosophical writings, which, despite their occasional flashes of insight and wit, can appear dense and convoluted to a modern reader.

I’m by no means the first writer to have been captivated by Bruno and what he stood for; James Joyce, Oscar Wilde and Berthold Brecht all made reference to him in fiction, and Victor Hugo was among the international contributors to the subscription campaign for his statue in Campo dei Fiori. My interest in him began at university, where I encountered him in the Elizabethan context of Sir Philip Sidney and Dr John Dee, in whose circle he moved, but my imagination was fired by a new interpretation of his contribution to 16th-century history which I discovered some years later.

As if Bruno’s peripatetic life and constant conflict with authority didn’t offer drama enough, in 1991 the English historian John Bossy published Giordano Bruno and the Embassy Affair, in which he attempted to prove that Bruno had worked as a spy for Sir Francis Walsingham, Elizabeth I’s spymaster, while he was resident at the French embassy in London from 1583-5, and later in Paris. The supporting evidence relied heavily on speculation and was not widely accepted by fellow historians; even Bossy, in the preface to the 2002 reprint, conceded that he would now like to retract large parts of his argument.

But fiction need not be so scrupulous; it’s not implausible that Bruno, with his connections and his interest in religious politics, might have been well-placed to work undercover and, because it can’t be disproved, this hypothesis has been the basis of the series of novels I’ve been writing about Bruno’s life since 2009. Many English and American readers tell me they didn’t realise he was a real historical figure when they started reading the books. Even in Europe, where his name is better known, few readers of popular fiction know much detail about his philosophy; they know only that he defied the authority of the Church, and was killed for it.

Bruno remains an outsider, and perhaps that is what gives his story its enduring power

I would argue that this doesn’t matter so much. If Bruno’s actual contributions to the history of Western thought have less to say to modern readers than his life story and the courage with which he defended those ideas to the death, it’s perhaps an inevitable consequence of our love of narrative, and of the trope of the lone maverick who is ultimately proved right. Bruno is easy to cast as a symbol of forward-looking, progressive, enlightened knowledge pitted against repressive religious conservatism; a man too far ahead of his time, just as he regarded Copernicus. In The Ash Wednesday Supper, he writes:

who will ever be able to praise sufficiently the greatness of this German* who, having little regard for the stupid mob, stood so firmly against the torrent of beliefs…? Who would not rather count him among those who, with happy genius, have been able to raise themselves and stand erect, most faithfully guided by the eye of Divine Intelligence?

(*Copernicus was Polish, though Bruno repeatedly refers to him as German.)

Bruno might have become the figurehead of choice for the students of a Rome newly independent of Papal authority after the Risorgimento (‘the generation he foresaw’); there might be piazzas, streets and colleges named after him all over Italy now, but his relationship to authority remains uneasy. His successor Galileo, who did recant when condemned by the Inquisition, was officially pardoned by Pope John Paul II in 1992, but as recently as 2000, on the 400th anniversary of Bruno’s death, the same Papal authority declared that the Nolan had deviated too far from Christian doctrine to be granted Christian pardon. Even now, he remains an outsider, and perhaps that is what gives his story its enduring power.

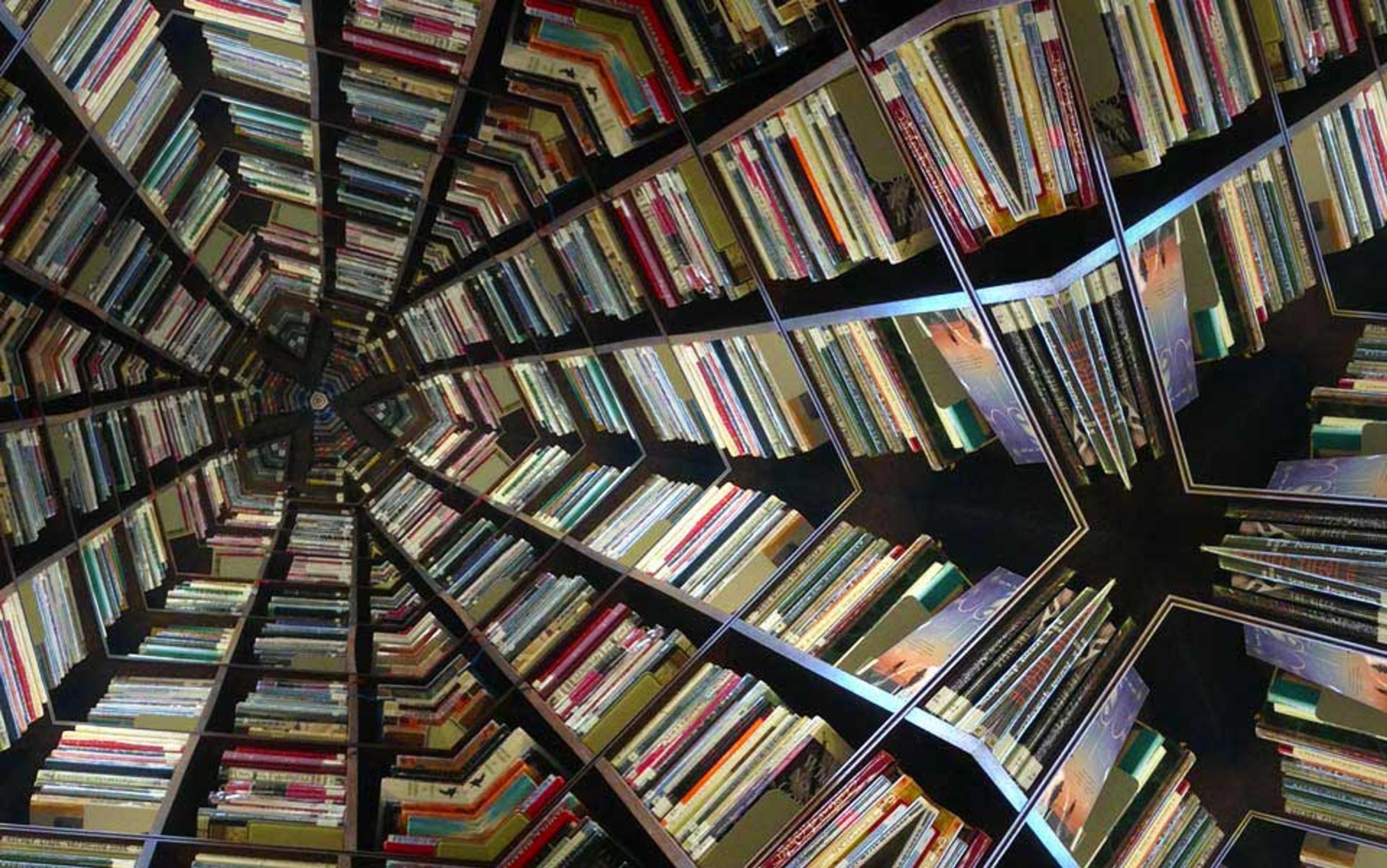

Last Christmas, a friend sent me a photograph from Cosenza in Calabria: a poster stuck to a public sculpture in the shape of a pile of books growing wings and taking flight. The poster showed a picture of Bruno’s statue, superimposed with the words ‘Ricordando Giordano Bruno, Contro Vecchi e Nuovi Inquisitori’ (Remembering Giordano Bruno, Against Old and New Inquisitors).

A few weeks earlier, I had heard him mentioned by the exiled Russian activist Nadezhda Tolokonnikova of Pussy Riot, at a fundraising gig for the Belarus Free Theatre, as part of a rousing speech about the past heroes who had given her courage to continue her protests. Perhaps the Inquisition is still with us, in different shapes, and each new generation he foresaw must not take its freedom of thought for granted. For as long as there are those who dare to voice their ideas aloud and are imprisoned or exiled for it, Bruno persists as a symbol of intellectual courage. Long may his flame burn.