Three archaeologists walk into a recently excavated prehistoric bar in Iceland. Athwart the barstools sit various skeletons, both human and dinosaur.

The first archaeologist, a self-styled secular empiricist, is fascinated by the establishment’s seating arrangements and brewing mechanisms, and begins a speculative essay on ‘the boozy habits of early man’. The dinosaur bones he dismisses with a smile as the work of a flim-flam artist. He declines to perform carbon-dating on the dinos.

The second archaeologist, a Biblical literalist, is meanwhile fascinated by the notion that man not only cohabited the Earth with dinosaurs – he drank with dinosaurs! This archaeologist promptly posts his findings to creationist Web portals. He also declines to perform carbon-dating on the dinos.

The third archaeologist, an Icelandic nationalist zealot, seizes upon the bar as evidence that Iceland was 12,000 years ahead of the rest of the world in terms of beer connoisseurship, drinking games, and hook‑up culture. He publishes a triumphalist paper hailing the primacy of the Icelandic race in light of these new findings. He doesn’t really give much thought to the dinosaurs at all.

Our story of the three archaeologists is fictional, to be sure, but it’s a useful parable about archaeological hoaxes, and the difficulty of uncoupling ideology from material history. There is a reason that we keep buying into hoaxes such as the ‘Shroud of Turin’ or the ‘Wife of Jesus’ fragment. Bad science makes for good stories.

The fossilised remains of a sea-serpent are much more interesting when you call them a dragon. And bad science is good for business. More important, it’s tempting to assign ourselves a larger role in the grand narrative of history, just as it’s tempting to go hunting for ancient proof of our most dearly held convictions.

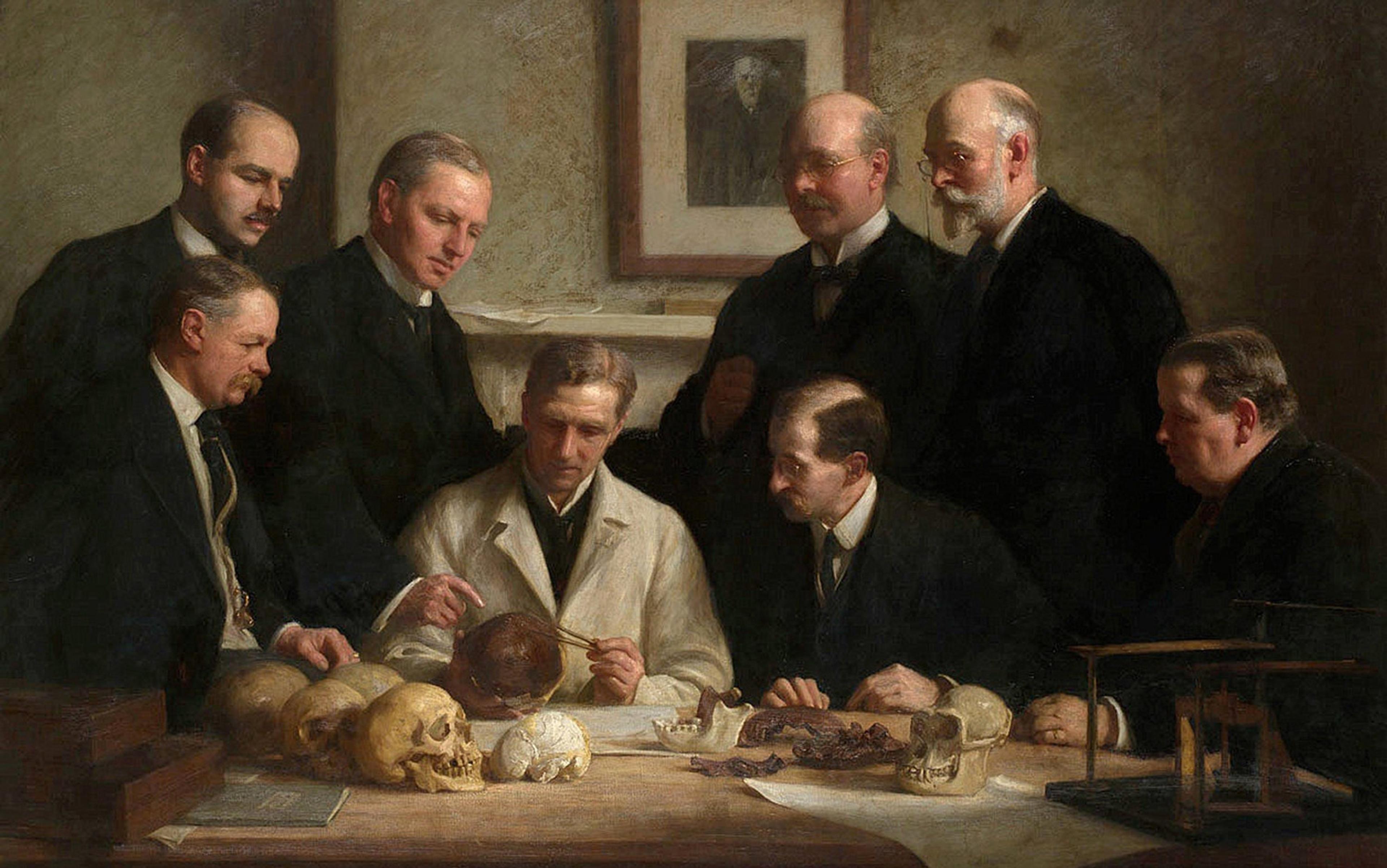

The best-laid archaeological hoaxes are often the hardest to assign a motive. Take the skull of Eoanthropus dawsoni, the ‘Piltdown Man’, exhumed in Sussex by the ardent British amateur archaeologist Charles Dawson around 1910. Dawson presented the remains – or rather the skull, wherein lay the creature’s chief interest – to the Geological Society of London in December 1912, to deafening ovations.

The Piltdown skull combined the jutting underbite of an ape with the cranium of a Homo sapiens. The New York Times Magazine expressed the common excitement over Dawson’s relic: ‘Paleolithic Skull Is Missing Link,’ gushed the American paper of record, calling the Piltdown creature ‘far older than cavemen’. The Times of London called Eoanthropus dawsoni ‘First Evidence of a New Human Type’.

It turned out to be a human skull retrofitted with an orangutan’s jaw and chimp’s teeth

For Brits, as the archaeologist Miles Russell writes in Piltdown Man: The Secret Life of Charles Dawson (2003), ‘the best news of all … was that the earliest known human was not French, German, Italian, Chinese, or African, but British’. For centuries, the English had amused themselves with origin myths: the Saxons were descended from Brutus (a notion that aligned Brittannia with Rome, and thereby sanctioned empire); and then there was Excalibur, or else St George and the Dragon; and isn’t it possible, as William Blake asks in the poem known as ‘Jerusalem’ (1808), that Jesus walked on England’s mountains green?

Before long, though, the Piltdown Man discovery unravelled, as did the imagined evolutionary primacy of Britons. Eoanthropus dawsoni turned out to be the skull of a human retrofitted with the jaw of an orangutan and the teeth of a chimp. The skull could not be more than half a millennium in age, and had clearly been treated with acid and metallic rust to achieve a veneer of prehistory. The myth that Britons had evolved earlier than other races vanished like the dew from a rose. Dawson was widely criticised afterwards, and it’s possible that Dawson was himself the victim of the hoax. Indeed, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle – the creator of Sherlock Holmes – was at one time suspected of having hoaxed Dawson.

The obsession with genetic primacy that so seduced Dawson appeared more recently – and more shamefully – in Japan. Whatever you might think of ‘observant amateurs’ such as Dawson, we should remember that the most infuriating frauds are wrought by experts.

The most famous such hoax was perpetrated by the Japanese archaeologist Shinichi Fujimura, former senior director at the Tohoku Paleolithic Institute. Fujimura’s colleagues used to call him ‘God’s hands’, on account of his extraordinary tendency to unearth breathtaking Paleolithic artifacts in the most unlikely corners of Japan.

Fujimura’s first marquee discovery was a variety of stoneware that his team dated at 40,000 years old; later discoveries dated back at least 500,000 years and included curiously advanced architectural ruins. Between 1980 and 2000, Fujimura excavated 150 to 200 sites in Japan and, like the Brits with Piltdown, his finds inevitably suggested that his country had been inhabited much, much longer than previously thought.

Japanese antiquarians were heard to mutter in private that some of these finds had been awfully convenient, and wasn’t it strange that Fujimura’s discoveries became more and more ancient – but Fujimura continued to publish, his colleagues nodded approval in the main, and Japan could pride herself on a far more ancient cultural lineage than anyone had previously imagined.

Thanks to Fujimura’s strong academic reputation, his ‘discoveries’ went unchallenged and soon appeared in textbooks. The forgeries, meanwhile, continued for so long and received sufficient consensus approbation that much of Paleolithic Japanese scholarship has been based on the Fujimura’s frauds.

‘There’s nothing more you can say. All our work over the years is as good as ruined’

The show fell apart in 2000, when the Mainichi Shimbun newspaper published video stills of Fujimura burying in the ground several artefacts he planned to unearth the next day. Fujimura’s reputation was promptly buried, too, and the Japanese archaeological establishment is in a sense still recovering. As the Archaeological Institute of America reported at the time:

In light of his confession, Fujimura’s involvement in several important discoveries at these sites has brought many fundamental ideas about Japan’s Palaeolithic – and the content of many textbooks – into question … The Tokyo National Museum has removed more than 20 artifacts discovered by Fujimura from display; other museums are following suit.

The Tohoku Paleolithic Institute is still recouping its reputation. Toshiaki Kamata, chairman of the institute, threw up his hands and resigned: ‘There’s nothing more you can say. With this media coverage, all our work over the years is as good as ruined.’

Perhaps most astonishing, Fujimura never really monetised his fraud – in fact, other than a nickname and a reputation in Tokyo, the archaeologist made very little, cash-wise, from his treachery. It appears that Fujimura wanted an older Japan, and if the ground wouldn’t yield up the right kind of stone-work, then he would have to supply the deficiency himself.

Ideology likewise predominates in the one school of archaeology that is basically immune to empirical debunking: religiously sanctioned archaeology. Indeed, some of the most bizarre hoaxes were motivated by religion. Certainly, the Church of Rome has enjoyed unimaginable lucre and goodwill thanks to its morbid collection of supposedly holy body parts. What wouldn’t we pay for the chance to rub a saintly femur, or a righteous clavicle? What ills of body or soul can withstand the holy power of a lock of hair?

Holier still is the relic that Charlemagne donated to Pope Leo III as thanks for the crown of the Empire. I am speaking of the sacrum praeputium, the Holy Prepuce – Christ’s supposed foreskin, a powerful dual emblem of the Mosaic and Pauline covenants. (How did Charlemagne lay hold of this wondrous slip of skin? He claimed it appeared in answer to a prayer, though others whispered that it was a gift from the Empress of Byzantium on the occasion of Charlemagne’s marriage. Wedding registries used to be much more interesting.)

This preposterous prepuce has inspired various imitations; in his article ‘Fore Shame’ published in Slate in 2006, David Farley writes that ‘depending on what you read, there were eight, 12, 14, or even 18 different holy foreskins in various European towns during the Middle Ages’. For centuries, the small town of Calcata, situated between Rome and Viterbo, claimed one of the oldest impostor-foreskins – until 1983, when it was stolen from a shoebox in the village priest’s wardrobe.

Such reliquaries are useful money-making schemes, for both the private cleric and the Church itself – until they suddenly are not, at which point they become embarrassments. Yet some items require a dual consciousness in the observer: take the Shroud of Turin, back on display in Italy, for the first time in five years, as of this April. Many devout Catholics who visit the shroud know that it’s not nearly old enough to be what it claims to be – yet in the past 700 years, the cloth has been invested with so much faith that it has become a significant artefact. The Shroud might have begun in falsehood, but it has become something meaningful through the projected belief of the faithful. This year, 1 million people have already made reservations to view it.

a 20th-century forger could easily have done the imperfectly archaic brushwork on a blank bit of ancient papyrus

The so-called ‘Wife of Jesus’ fragment has proved to be a less exciting draw to Catholic pilgrims since its public début in 2012. This Coptic papyrus, in which Jesus refers to ‘my wife’, is the antipode of the Turin shroud: rather than blithely confirming the synoptic gospels, this papyrus subverts Rome’s most cherished notions about Christ – that Jesus privileged male disciples over female disciples, and that Christ’s celibacy is the emulative duty of all Christian clerics.

In both composition and syntax, the ‘Wife of Jesus’ fragment is suspect: the Coptic brushwork (in place of the more traditional reed pen) is awkward about its indirect objects, and though Harvard estimates that the papyrus itself dates to the eighth century AD, researchers also acknowledge that a 20th-century forger could easily have done the imperfectly archaic brushwork on a blank bit of ancient papyrus.

While palaeographers might snort at the ‘Wife of Jesus’ fragment, its ‘discovery’ has at least spurred renewed and vigorous interest in the role of women among Christ’s disciples – the Marys, an apostle named Junia, and Phoebe, whom Paul described to the Romans as a ‘deacon’ (the Greek diakonos). The theologists Joel Baden of Yale and Candida Moss of the University of Notre Dame, writing last year in The Atlantic, note that:

For the most part, the texts and narratives that support the notion of female discipleship come from outside the traditional canon – no surprise, really, given that the canonical New Testament was assembled long after Jesus’ death by a male-led Church.

If the ‘Wife of Jesus’ fragment truly is a fraud, we can understand the impulse: to reclaim religious experience from those who would construe it as a province dominated by males, and to reclaim a version of Christ who cedes an equal role to women among his most intimate circles of worship.

The New World offered unbroken ground for credulous – or hucksterish – diggers, especially in the American West. This is one reason that, of all the Western revealed religions, no sect depends so much on bad archaeology as the Mormon Church. There are the golden plates in upstate New York to which, circa 1823, the angel Moroni directed Joseph Smith, who would go on to found the Latter Day Saint movement. Smith did impressive work translating the pseudo-Egyptian of the plates into the new golden gospel, but then Moroni had the kind foresight to supply the Mormon forefather with ‘seer stones’, the ecclesiastical version of the secret decoder rings that used to be available at the bottom of cereal boxes.

In 1843, three wags ‘excavated’ six graven pieces of copper from a Native American burial ground and presented them to Smith, who translated what came to be called the ‘Kinderhook Plates’, after the town in Illinois where they were supposedly found. One of the three pranksters, a local man named Wilbur Fugate, wrote in a letter that he was pulling the leg of Smith and his fellow first-generation Mormon Orson Pratt. (In fact, Bridge Witton, a blacksmith, wrought the Kinderhook Plates before the men planted them.)

A few years later in 1862, the author Mark Twain would embarrass a Nevada judge with a completely fictional newspaper account of discovering a petrified man complete with a wooden leg (‘every limb and feature of the stony mummy was perfect, not even excepting the left leg, which has evidently been a wooden one during the lifetime of the owner’; the piece was nationally syndicated), and the University of Arizona very nearly bought the relics of a supposed eighth-century settlement of Roman Jews in Phoenix.

The mythology of the New World engendered a mania for reinvigorating Old-World myths in a land that still felt only half-real

The salvific obsession with gold was accompanied by a sense that the earth of the New World might house the transposed treasures of Near-Eastern antiquity, a sense that lent credence to the tallest of tales, the oddest of artefacts. This same New World bewitched the Spanish explorer Juan Ponce de León with promises of the Fountain of Youth, and lured the British officer Percy Fawcett and son to seek Atlantis in the jungles of Brazil where they found only death.

The mythology of the New World – as expansive as the continent itself – engendered a mania for magical thinking, for reinvigorating Old-World myths in a land that still felt only half-real. In the New World, true believers and hucksters alike learned to gather old myths newly transposed – some for knowledge, others for faith, and their more craven counterparts for money, or to satisfy a grudge. Where Fujimura embedded false history, Americans – whether cynical or credulous – imported it. As Fujimura, and Dawson before him, knew, a land without myths can be a lonely place.

But there is likewise a secret pleasure in loneliness when that loneliness gives you an advantage over your fellows. Among the most devious hucksters, including Twain, we see a frantic secrecy, an illicit joy known only to the mystic, the madman, and the solitary assassin – the drive to know something about the world that nobody else does.

In fiction, Sherlock Holmes attests the exhilaration that comes from being the sole proprietor of a fact. Create something false, convince someone it’s real, and your knowledge of that falsity becomes a fact known only to you. After Twain’s initial astonishment that anyone could have taken his ‘petrified man’ piece seriously – ‘a string of roaring absurdities’, he called it – he noted ‘a soothing secret satisfaction’ at the success of the jape. We can only wonder what private joys Fujimura experienced before the fall. The age of miracles may well have passed, but myth will always have a ready audience.