As I prepared to teach my class ‘Science and Islam’ last spring, I noticed something peculiar about the book I was about to assign to my students. It wasn’t the text – a wonderful translation of a medieval Arabic encyclopaedia – but the cover. Its illustration showed scholars in turbans and medieval Middle Eastern dress, examining the starry sky through telescopes. The miniature purported to be from the premodern Middle East, but something was off.

Besides the colours being a bit too vivid, and the brushstrokes a little too clean, what perturbed me were the telescopes. The telescope was known in the Middle East after Galileo developed it in the 17th century, but almost no illustrations or miniatures ever depicted such an object. When I tracked down the full image, two more figures emerged: one also looking through a telescope, while the other jotted down notes while his hand spun a globe – another instrument that was rarely drawn. The starkest contradiction, however, was the quill in the fourth figure’s hand. Middle Eastern scholars had always used reed pens to write. By now there was no denying it: the cover illustration was a modern-day forgery, masquerading as a medieval illustration.

The full image of the 21st century fake Ottoman miniature, purporting to be from the 17th century. Allegedly from the Istanbul University Library. Photo by DEA/Getty

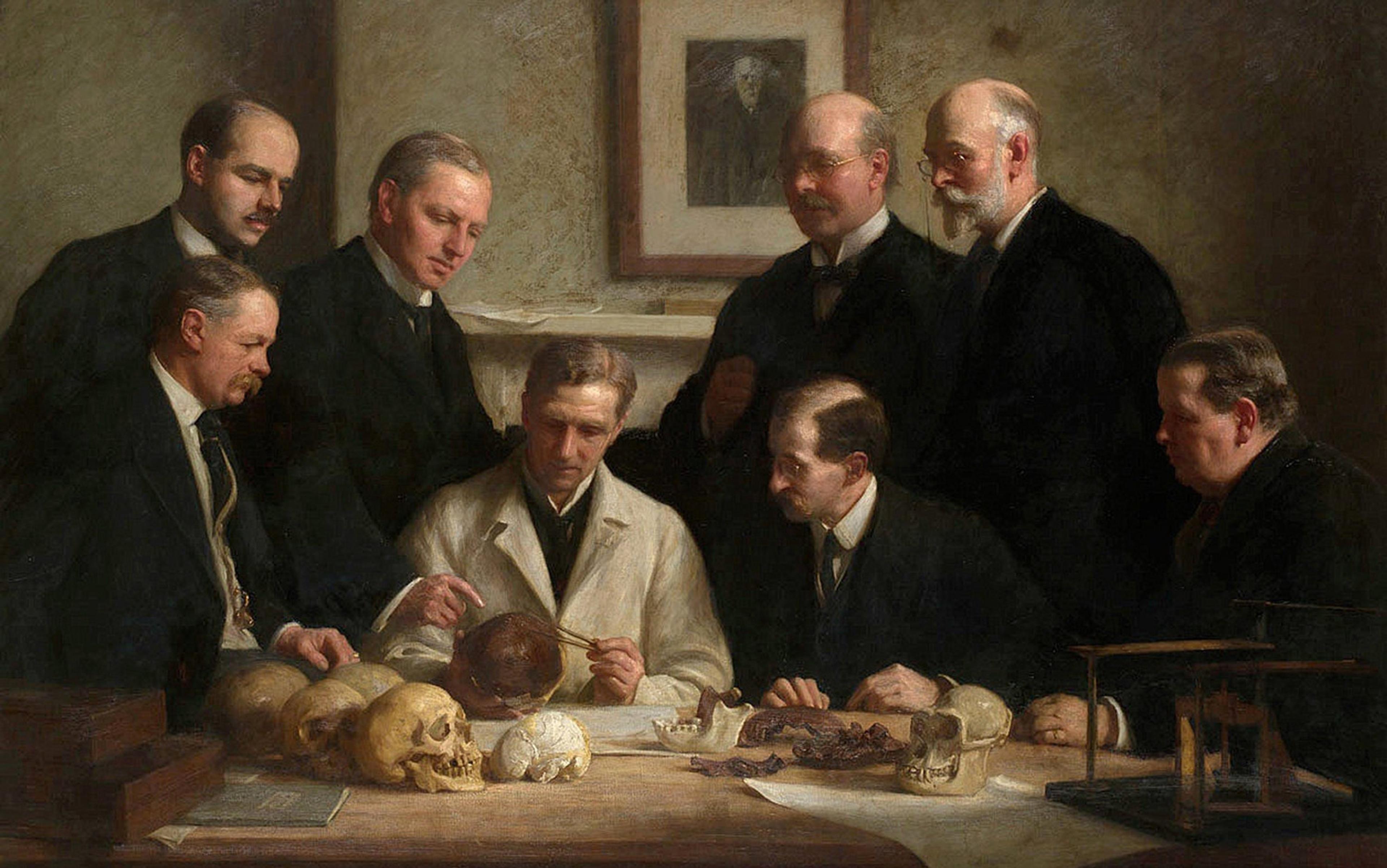

The fake miniature depicting Muslim astronomers is far from an isolated case. One popular image floating around Facebook and Pinterest has worm-like demons cavorting inside a molar. It claims to illustrate the Ottoman conception of dental cavities, a rendition of which has now entered Oxford’s Bodleian Library as part of its collection on ‘Masterpieces of the non-Western book’. Another shows a physician treating a man with what appears to be smallpox. These contemporary images are in fact not ‘reproductions’ but ‘productions’ and even fakes – made to appeal to a contemporary audience by claiming to depict the science of a distant Islamic past.

A fake miniature depicting the preparation of medicines for the treatment of a patient suffering from smallpox, purportedly from the Canon of Medicine by Avicenna (980-1037). Allegedly in the Istanbul University Library. Photo by Getty

From Istanbul’s tourist shops, these works have ventured far afield. They have have found their way into conference posters, education websites, and museum and library collections. The problem goes beyond gullible tourists and the occasional academic being duped: many of those who study and publicly present the history of Islamic science have committed themselves to a similar sort of fakery. There now exist entire museums filled with reimagined objects, fashioned in the past 20 years but intended to represent the venerable scientific traditions of the Islamic world.

The irony is that these fake miniatures and objects are the product of a well-intentioned desire: a desire to integrate Muslims into a global political community through the universal narrative of science. That wish seems all the more pressing in the face of a rising tide of Islamophobia. To be clear, Muslims always conducted science, despite the claims of Islamophobes to the contrary, but often it wasn’t visually expressed in a way that we find easy to recognise today. But what happens when we start fabricating objects for the tales we want to tell? Why do we reject the real material remnants of the Islamic past for their confected counterparts? What exactly is the picture of science in Islam that are we hoping to find? These fakes reveal more than just a preference for fiction over truth. Instead, they point to a larger problem about the expectations that scholars and the public alike saddle upon the Islamic past and its scientific legacy.

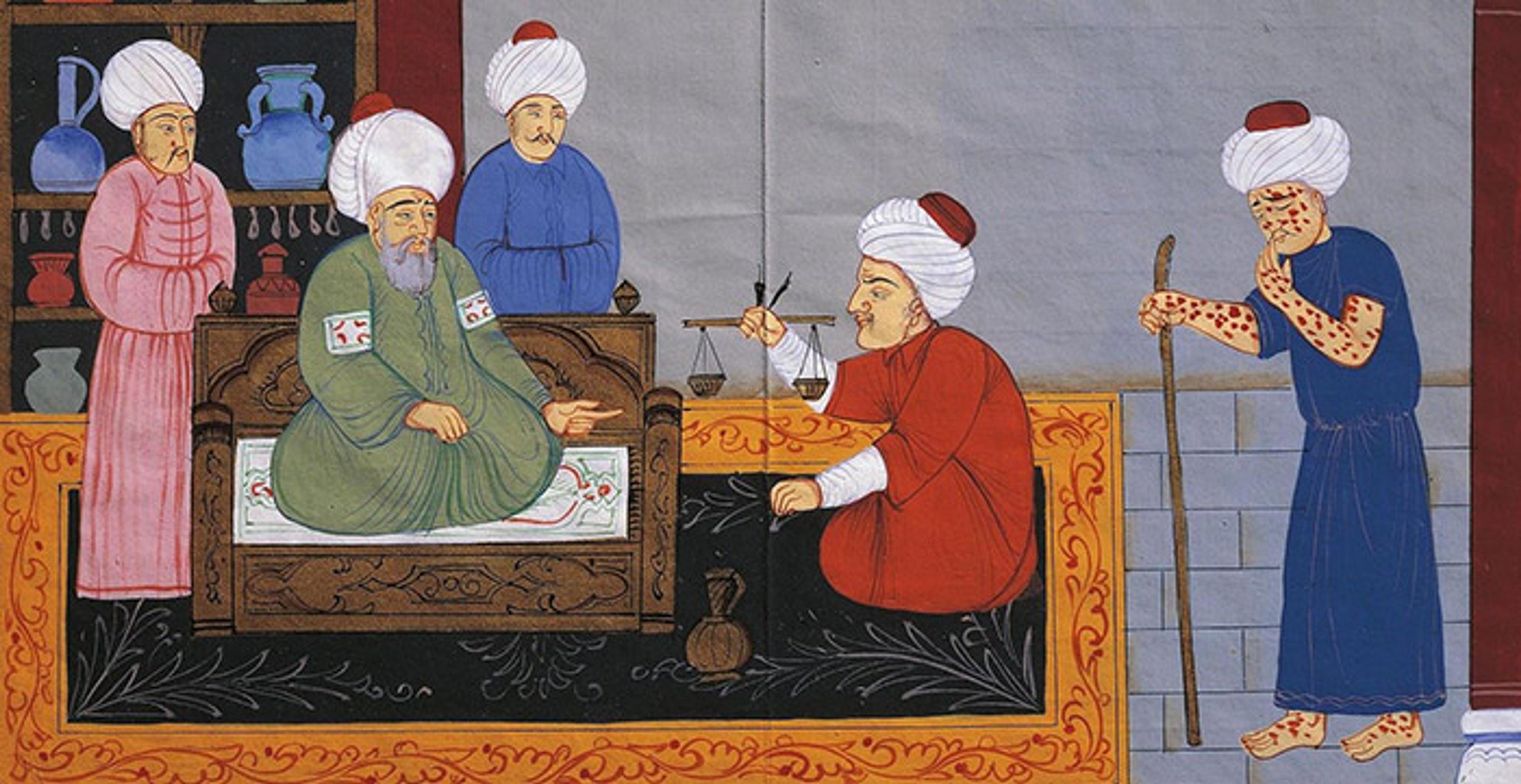

There aren’t many books left in the old booksellers’ market in Istanbul today – but there are quite a few fake miniatures, sold to the tourists flocking to the Grand Bazaar next door. Some of these miniatures show images of ships or monsters, while others prompt a juvenile giggle with their display of sexual acts. Often, they’re accompanied by some gibberish Arabic written in a shaky hand. Many, perhaps the majority, are depictions of science in the Middle East: a pharmacist selling drugs to turbaned men, a doctor castrating a hermaphrodite, a group of scholars gazing through a telescope or gathering around a map.

Fake miniatures for sale in the Booksellers Market (Sahaflar Çarsısı) in Istanbul. Photo courtesy of the author.

To the discerning eye, most of the miniatures these men sell are recognisably fake. The artificial pigments are too bright, the subject matter too crude. Unsurprisingly, they still find willing buyers among local and foreign tourists. Some images, on occasion, state that they are modern creations, with the artist signing off with a recent date in the Islamic calendar. Others are more duplicitous. The forgers tear pages out of old manuscripts and printed books, and paint over the text to give the veneer of old writing and paper. They can even stamp fake ownership seals onto the image.

With these additions, the miniatures quickly become difficult to identify as fraudulent once they leave the confines of the market and make their way on to the internet. Stock photo services in particular play a key role in disseminating these images, making them readily available to use in presentations and articles in blogs and magazines. From there, the pictures move on to the main platforms of our vernacularised visual culture: Instagram, Facebook, Pinterest, Google. In this digital environment, even experts on the Islamic world can mistake these images for the authentic and antique.

The forger transforms a scholar raising a sextant to his eye into a man using a telescope

The internet itself has become a source of fantastic inspiration for forgers. The drawing supposedly depicting the Ottoman view of dental cavities, for example, emerged after a similar picture of an 18th-century French ivory surfaced on the internet. Other forgers simply copy well-known miniatures, such as the illustration of the short-lived observatory in 16th-century Istanbul, in which turbaned men take measurements with a variety of instruments on a table. This miniature – reliably located in the Rare Books Library of Istanbul University – is found in a Persian chronicle praising Sultan Murad III, who ordered the observatory built in 1574, and subsequently had it demolished a few years afterwards.

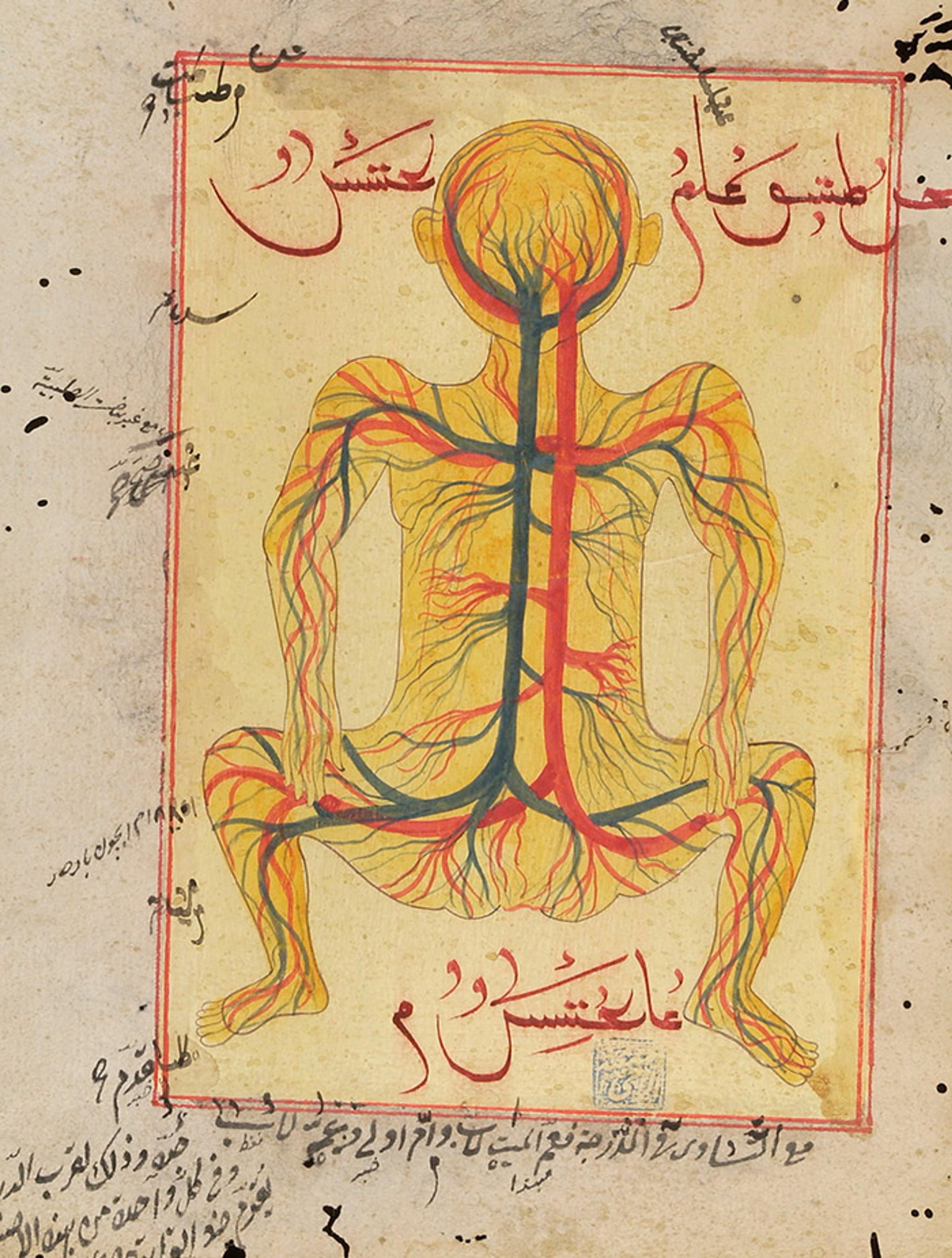

Even if its imitations look crude, they still find audiences – such as those who visit the 2013 ‘Science in Islam’ exhibition website at the Museum of the History of Science in Oxford. The site, which aims to educate secondary-school children, took the image from a similar site run by the Whipple Museum of the History of Science at the University of Cambridge – which in turn acquired it a year earlier from a dealer in Istanbul, according to the museum’s own records. Meanwhile, another well-respected institution, the Wellcome Collection in London, specialises in objects from the history of medicine; it includes several poorly copied miniatures demonstrating Islamic models of the body, written over with a bizarre pseudo-Arabic and with no given source.

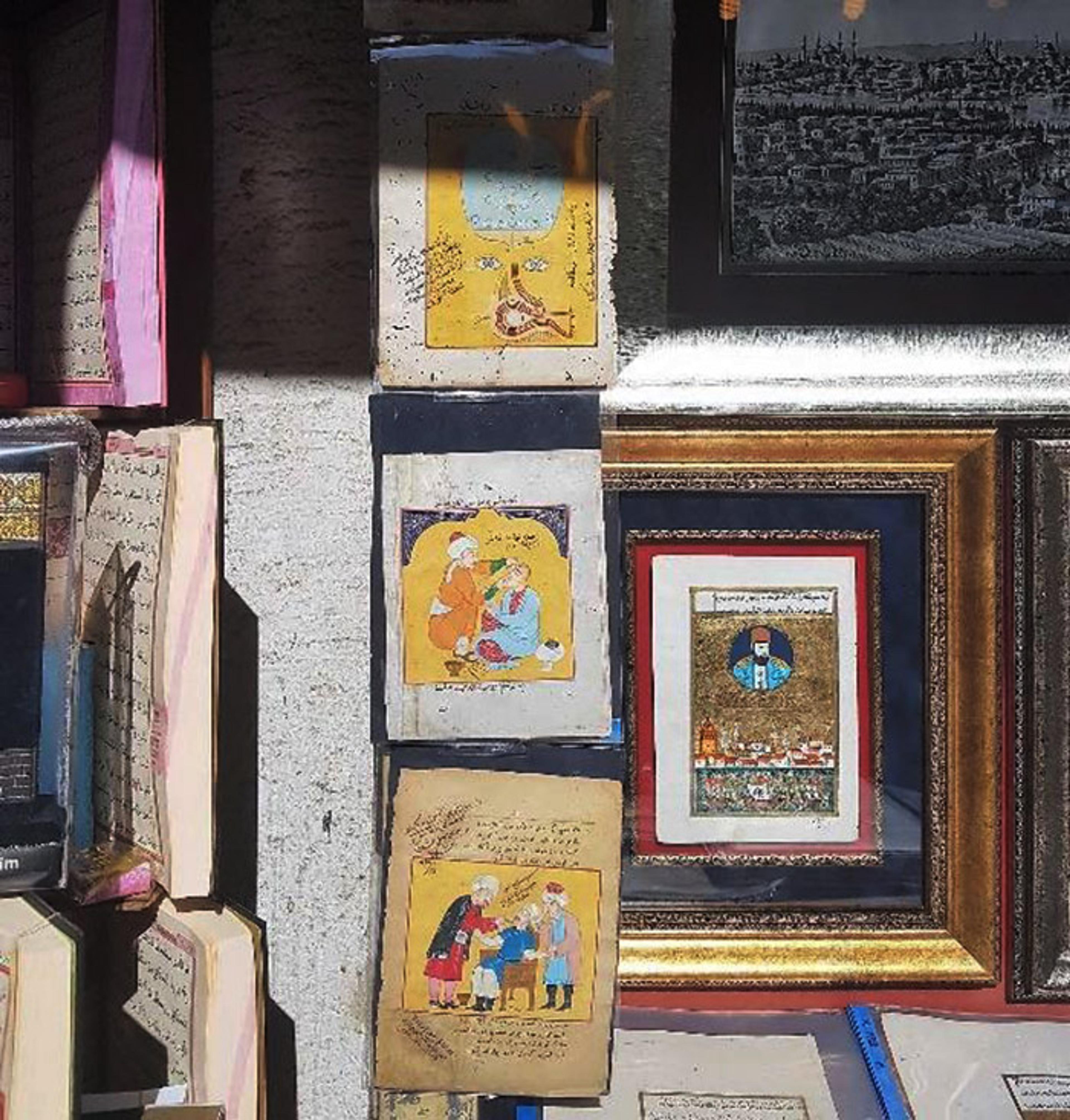

A fake anatomical diagram with nonsensical, Arabic-like script, supposedly depicting an Islamic model of the veins and arteries of the body. Photo courtesy of the Wellcome Collection.

A few images, though, are invented from whole cloth, such as a depiction of a man with what appears to be smallpox, nervously consulting with a pharmacist and doctor. More troubling still are the images that artists alter to match our own expectations. The picture on the cover of the book I was going to assign my students, with men looking at the night sky through a telescope, borrows from the figures in the Istanbul observatory miniature. However, the forger easily transforms a scholar raising a sextant to his eye, to measure the angular distance between astronomical bodies, into a man using a telescope in the same pose. It is a subtle change but it alters the meaning of the image significantly – pasting in an instrument of which we have no visual depictions in Islamic sources, but that we readily associate with the act of astronomy today.

In the corner of Gülhane Park in Istanbul, down the hill from the former Ottoman palace and Hagia Sofia, lies the Museum for the History of Science and Technology in Islam (İslam Bilim ve Teknoloji Tarihi Müzesi). A visitor begins with astronomical instruments – astrolabes and quadrants (thankfully, no telescopes). As you move through the displays, the exhibits shift from instruments of war and optics to examples of chemistry and mechanics, becoming increasingly fantastical with each room. Glass cages of beakers follow alembics in elaborate contraptions. At the end, one reaches the section on engineering. Here, you find the bizarre machines of Ismail al-Jazari, a 12th-century scholar often called the Muslim father of engineering. His contraptions resemble medieval versions of Rube Goldberg machines: think of a water clock in the shape of a mahout, sitting on top of an elephant or other pieces.

There’s only one catch. All the objects on display are actually reproductions or completely imagined objects. None of the objects is older than a decade or two, and indeed there are no historical objects in the museum at all. Instead, the astrolabes and quadrants, for example, are recreated from pieces in other museums. The war machines and the giant astronomical instruments are typically scaled-down models that can fit in a medium-sized room. The intricate chemistry contraptions, of which no copy has ever been found in the Middle East, are created solely to populate the museum.

By itself, this conjuring act isn’t necessarily a problem. Some of the pieces are genuinely rare, and others might not exist today but are useful to see recreated in models and miniatures. What makes this museum unique is its near total refusal to collect actual historical objects. The museum never explicitly addresses or justifies the fact that its entire collection is composed of recreations; it simply presents them in glass display cases, with no attempt to situate them in a narrative about the history of the Middle East, other than simply stating the dates and location of their originals.

Both the fakes and the museum are meant to evoke wonder in the viewers today

The origins of the bulk of the museum’s collection becomes clearer when you look at the photographs behind the displays: many objects were recreated from the illustrations of medieval manuscripts containing similar-looking devices. The most famous of these are the extraordinary images of al-Jazari’s contraptions, taken from his book The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices. While the machines should work, in theory, none has been known to survive. It might even be that their designer didn’t intend them to be built in the first place.

Just what is the role of a museum, specifically a history museum, that contains no genuine historical objects? Istanbul’s museum of Islamic science isn’t an isolated case. The same approach marks the Sabuncuoğlu History of Medicine Museum in Amasya in northern Turkey, as well as the Leonardo da Vinci museum in Milan, which brings to life the feverish mechanisms that the inventor sketched out in the pages of his notebooks.

Unlike the fake miniatures, these institutions weren’t built with the purpose of duping unsuspecting tourists and museums. The man behind the Islamic science museum in Istanbul is the late Fuat Sezgin, formerly at the University of Frankfurt. He was a respected scholar who compiled and published multiple sources on Islamic science. But his project shares certain key qualities with the fake miniatures. They create objects that adhere to our contemporary understandings of what ‘doing science’ looks like, and treat images of Islamic science as if they are literal and direct representations of objects and people that existed in the past.

Most importantly, perhaps, both the fakes and the museum are meant to evoke wonder in the viewers today. There is nothing inherently wrong with wonder, of course; it can spur viewers to question and investigate the natural world. Zakariya al-Qazwini, the 13th-century author who described the world’s curious and spectacular phenomena in his book Wonders of Creation, defined wonder as that ‘sense of bewilderment a person feels because of his inability to understand the cause of a thing’. Princes used to read the heavily illustrated books of al-Jazari in this manner, not as practical engineering manuals, but as descriptions of devices that were beyond their comprehension. And we still look at al-Jazari’s recreated items with a sense of awe, even if we now grasp their mechanics – just that, today, we marvel at the fact that they were made by Muslims.

What drives the spread of these images and objects is the desire to use some totemic vision of science to redeem Islam – as a religion, culture or people – from the Islamophobia of recent times. Equating science and technology with modernity is common enough. Before the current political toxicity took hold, I would have taught a class on Arab Science, rather than Islam and Science. Yet in a world that’s all too willing to vilify Islam as the antithesis of civilisation, it seems better to try and uphold a message that science is a global project in which all of humanity has participated.

This embracing sentiment sits behind ‘1,001 Inventions’, a travelling exhibit on Islamic science that has frequented many of the world’s museums, and has now become a permanent, peripatetic entity. The feel-good motto reads: ‘Discover a Golden Age, Inspire a Better Future’. To non-Muslims, this might suggest that the followers of Islam are rational beings after all, capable of taking part in a shared civilisation. To Muslim believers, meanwhile, it might imply that a lost world of technological mastery was indeed available to them, had they remained on the straight path. In this way, ‘1,001 Inventions’ draws an almost direct line between reported flight from the top of Galata Tower in 17th-century Istanbul and 20th-century Moon exploration.

With these ideals in mind, do the ends justify the means? Using a reproduction or fake to draw attention to the rich and oft-overlooked intellectual legacy of the Middle East and South Asia might be a small price to pay for widening the circle of cross-cultural curiosity. If the material remains of the science do not exist, or don’t fit the narrative we wish to construct, then maybe it’s acceptable to imaginatively reconstruct them. Faced with the gap between our scant knowledge of the actual intellectual endeavours of bygone Muslims, and the imagined Islamic past upon which we’ve laid our weighty expectations, we indulge in the ‘freedom’ to recreate. Textbooks and museums rush to publish proof of Muslims’ scientific exploits. In this way, wittingly and unwittingly, they propagate images that they believe exemplify an idealised version of Islamic science: those telescopes, clocks, machines and medical instruments that cry ‘modernity!’ to even the most casual or skeptical observer.

However, there is a dark side to this progressive impulse. It is an offshoot of a creeping, and paternalistic, tendency to reject the real pieces of Islamic heritage for its reimagined counterparts. Something is lost when we reduce the Islamic history of science to a few recognisably modern objects, and go so far as to summon up images from thin air. We lose sight of important traditions of learning that were not visually depicted, whether artisanal or scholastic. We also leave out those domains later deemed irrational or unmodern, such as alchemy and astrology.

This selection is not just a question of preferences, but also of priorities. Instead of spending millions of dollars to build and house these reimagined productions, museums could have bought, collected and gathered actual objects. Until recently, for instance, Rebul Pharmacy in Istanbul displayed its own private collection of historical medical instruments – whereas the Museum for the History of Science and Technology in Islam chose to craft new ones. A purposeful choice has therefore been made to ignore existing objects, because what does remain doesn’t lend itself to the narrative that the museum wishes to tell.

The false miniatures are painted on the ripped-out pages of centuries-old manuscripts to add to their historicity

Perhaps there’s a worry that the actual remnants of Islamic science simply can’t arouse the necessary wonder; perhaps they can’t properly reveal that Muslims, too, created works of recognisable genius. Using actual artefacts to achieve this end might demand more of viewers, and require a different and more involved mode of explanation. But failing to embrace this challenge means we lose an opportunity to expand the scope of what counted as genius or reflected wonder in the Islamic past. This flattening of time and space impoverishes audiences and palliates their prejudices, without their knowledge and even while posing as enrichment.

We’re still left with the question, though, of the harm done by the proliferation of these reimagined images and objects. When I’ve raised it with colleagues, some have argued that, even if these works are inauthentic, at least they invite students to learn about the premodern Middle East. The sentiment would be familiar to the historian Anthony Grafton, who has observed that the line between the forger and critic is extremely thin. Each sets out, with many of the same tools, to make the past relevant according to the changing circumstances of the present. It’s just that, while the forger dresses new objects in the clothes of the past to fit our current concerns, the critic explains that today’s circumstances differ from those of the past, and retains and discards certain aspects as she sees fit.

Grafton ultimately sides with the critic: the forger, he says, is fundamentally ‘irresponsible; however good his ends and elegant his techniques, he lies. It seems inevitable, then, that a culture that tolerates forgery will debase its own intellectual currency, sometimes past redemption.’ As fakes and fictions enter our digital bloodstream, they start to replace the original images, and transform our baseline notions of what actually was the science of the past. In the case of the false miniatures, many are painted on the ripped-out pages of centuries-old manuscripts to add to their historicity, literally destroying authentic artefacts to craft new forgeries.

In an era when merchants of doubt and propagators of fake news manipulate public discourse, recommitting ourselves to transparency and critique seems like the only solution. Certainly, a good dose of these virtues is part of any cure. But in all these cases, as with the museum, it’s never quite clear who bears responsibility for the deception. We often wish to discover a scheming mastermind behind every act of forgery, whether the Russian state or a disgruntled pseudo-academic – exploiting the social bonds of our trust, and whose fraud can be rectified only by a greater authority. The responsibility to establish truth, however, doesn’t only lie in the hands of the critics and forgers, but also in our own actions as consumers and disseminators. Each time we choose to share an image online, or patronise certain museums, we lend them credibility. Yet, the solution might also demand more than a simple reassertion of the value of truth over fiction, of facts over lies. After all, every work of history, whether a book or a museum, is also partially an act of fiction in its attempt to recount a past that we can no longer access.

A mile away from the museum of Islamic science in Istanbul, nestled in the alleys of the Çukurcuma neighbourhood, resides another museum of invented objects and tales. This one, though, is dedicated not to Islamic scientific inventions but to an author’s melancholic vision of love and, as it happens, Istanbul’s material past. The Museum of Innocence is the handiwork of the Turkish Nobel Prize-winning novelist Orhan Pamuk, whose collected and created objects form the skeleton upon which his 2008 book of the same name is built. Its protagonist, Kemal, slowly leads the reader and the museum-goer through his aborted relationship with his beloved, Füsun. Each chapter corresponds to one of the museum’s small dioramas, which exhibit a collection of objects from the novel. Vintage restaurant cards, old rakı bottles and miniature ceramic dogs to be placed atop television sets are delicately arranged in little displays, often with Pamuk’s own paintings as a backdrop.

Behind the museum, though, lies a fictional narrative – and that very fact destabilises our expectations of what the objects in a museum can and should do. Did Pamuk write the novel and then collect objects to fit it, or vice versa? It’s never entirely clear which came first. Pamuk’s opus confronts us with a question: do we tell stories from the objects we collect, or do we collect the objects to tell the stories we desire? The different approaches are, in fact, two sides of the same coin. We collect materials that adhere to our imagined stories, and we craft our narratives according to the objects and sources at hand.

The Museum of Innocence occupies a special place on a spectrum of possibility about how we interact with history. At opposite ends of this spectrum sit the fake miniatures and the fantastical objects of Islamic science, respectively. The miniatures circulate on the internet on their own, often removed from any narrative and divorced from their original sources, open to any interpretation that a viewer sees fit. By contrast, the constructed objects in museums of Islamic science have been consciously brought into this world to serve a defensive narrative of Muslim genius – a narrative that the museums’ founders believed they couldn’t extract from the actual historical objects.

Pamuk’s museum, though, strikes a balance. As one stands in front of Pamuk’s exhibits of pocket watches and photographs of beauty pageants, one slowly examines the objects, imagining how they were used, perhaps listening to a recording of Pamuk’s stories to animate them. It is through his display cases, paintings and writing that the objects come to life. Yet, viewers also see the bottles of rakı and other ephemera outside the confines of Pamuk’s narrative. He displays a commitment to the objects themselves, and lets them tell their tale without holding a naive belief in their objective power. This approach grants Pamuk’s museum an intellectual honesty lacking in Sezgin’s museum of Islamic science.

By neglecting actual historical objects, and championing their reimagined counterparts, we efface the past

What is ultimately missing from the fake miniatures, and from the Museum for the History of Science and Technology in Islam, are the very lives of the individuals that fill Pamuk’s museum. Faced with fantasy or forgery, we are left to stand in awe of the telescopes and alembics, marvelling that Muslims built them, but knowing little of the actual artisans and scholars, Muslim and non-Muslim alike. In these lives lies the true history of science in Islamic world: a midwife’s preparation of herbs; a hospital doctor’s list of medicines for the pious poor; an astrologer’s horoscope for an aspiring lieutenant; an imam’s astronomical measurements for timing the call to prayer; a logician’s trial of a new syllogism; a silversmith’s metallurgic experimentation; an encyclopaedist’s classification of plants; or a judge’s algebraic calculations for dividing an inheritance. These lives are not easily researched, as demonstrated by the anaemic state of the field. However, by refusing to collect and display actual historical objects, and instead championing their reimagined counterparts, we efface these people of the past.

Focusing on these lives requires some fiction, to be sure. A museum or book would have to embrace the absences and gaps in our knowledge. Instead of shyly nudging the actual objects out of view, and filling the lacunae with fabrications, it would need to bring actual historical artefacts to the fore. It might take inspiration from the Whipple Museum and even collect forgeries of scientific instruments as important cultural objects in their own right. Yes, we might have to abandon the clickbaity pictures of turbaned astronomers with telescopes that our image-obsessed culture seems to crave. We would have to adapt a different vision of science and of visual culture, a subtler one that does not reduce scientific practice to a few emblems of modernity. But perhaps this is what it means to cultivate a ‘sense of bewilderment’, to use al-Qazwini’s phrase – a new sense of wonder that elicits marvel from the lives of women and men in the past. That would be a genuinely fresh form of seeing; an acknowledgement that something can be valuable, even when we do not recognise it.

The writer wishes to thank the following people for their help in tracking down the origins of some of the fake miniatures: Elias Muhanna, the author of the book at the beginning of the essay; Josh Nall, the curator of the Whipple Museum of History of Science in Cambridge; and Christiane Gruber, a professor in the history of art at the University of Michigan.