Ten years ago, one of the most disruptive events in my intellectual life occurred at a dinner party at my house. My friend Richard Thomas, who had just given a talk at Baylor University, mentioned that a student of his had discovered an ‘Isaiah acrostic’ in Vergil’s Georgics, a 1st-century BCE poem ostensibly about farming but really about life and the universe. This remark simultaneously opened the door to two phenomena in ancient Greek and Latin poetry that I had not really thought about, despite a lifelong career in Classics: acrostics and Judaism.

The relationship between the biblical and the classical traditions has always been fraught. As Tertullian testily asked in his screed against pagan writers: ‘What has Athens to do with Jerusalem?’ Similarly, St Jerome felt compelled to abandon the classical authors he loved after a nightmare vision in which the judge accused him of being a Ciceronian, not a Christian. One of the many reasons Vergil is central to the Western tradition is that his Fourth Eclogue, which portrays the birth of a miraculous boy ‘sent down from heaven’ to inaugurate a new Golden Age, helped calm these fears: it was seen by readers from late antiquity until the 18th century as a pagan prophecy of the birth of Christ, thereby allowing Christianity to assimilate the Classics rather than merely rejecting them. Post-Enlightenment readers, however, tended to react against the Christian interpretation – they had no desire to view Athens through the prism of Jerusalem.

Whatever one may think about the supernatural dimension, there is abundant evidence for personal and intellectual contact between Jews and non-Jewish Greeks and Romans before and after the birth of Christ. Jews composed something like 10-20 per cent of the population of the Roman Empire; there are many overt references to Jews and Judaism in classical texts; and the Septuagint – the Greek translation of the Hebrew scriptures undertaken in the 3rd century BCE – would have been accessible to educated non-Jewish people throughout the Mediterranean world. Classicists and intellectual historians should be paying far more attention than they presently do to the impact of Jewish texts and culture on classical authors. In my paper ‘Was Vergil Reading the Bible?’ (2018), I argued that the answer to that question is probably ‘Yes’, and that at least some scholars are beginning to realise that Jewish themes are an important component of his meaning.

Scholars’ lack of attention to acrostics, on the other hand, may stem more from an intuitive sense that they are beneath the dignity of sophisticated authors. Indeed, acrostics are an art form simple enough for a child to create. The most basic kind is a word spelled vertically by the first letters of successive lines:

Catches mice,

Adorable whiskers,

Tail’s up – look out!

That such vertical words exist in the columns of long poems is undeniable; the difficulty consists in figuring out whether they are intentional. The vertical CAT above has such an obvious connection to the horizontal text that no one could reasonably deny its intentionality. But when acrostics are embedded in real poetry and no one is telling you to look for them, most are not so obvious.

As with any disruptive phenomenon, there are both enthusiasts, whose close-meshed nets catch some dubious fish, and deniers, who insist that even the big ones should be thrown back. For many years, insanity was a common metaphor employed for those who believe acrostics in ancient poetry are intentional. The most influential one-paragraph Classics article ever written, Don Fowler’s playful intervention about the acrostic MARS spanning Vergil’s description of the Gates of War, ends with the memorable sentence: ‘I await the men in white coats.’ What Fowler did not anticipate was that, four decades later, acrostics would begin to be recognised as not just an occasional jeu d’esprit in ancient poetry, but a widespread phenomenon and a major source of meaning.

Acrostics always have, in theory, plausible deniability

There are several reasons why believing that some acrostics in Greek and Latin poetry are intentional is both sane and rewarding. First, ancient writing and reading practices were more congenial than ours to letterplay and vertical ‘decoding’. Texts consisted of blocks of capital letters with no spaces in between, rather like our word-search puzzles. As one unrolled a scroll, the columns would appear before the rows, and sometimes the first letters of verses were even enlarged and separated by dots. Second, ancient authors such as Cicero actually talk about acrostics, especially in the context of the Sibylline Oracles. Third, the vertical axis allows for both permanently unresolvable ambiguities, which is a plus for learned writers conveying complex messages, and the addition of a ‘voice’ freed from the horizontal constraints of metre, authorial persona and decorum. Acrostics always have, in theory, plausible deniability – even if that deniability seems rather implausible sometimes, as in the modern example from Arnold Schwarzenegger to members of the California State Assembly. Fourth, they are delightful ‘Easter eggs’ for those hardy souls who read carefully, like the undergraduate student who published an article on an acrostic she had discovered during my class.

Finally, vertical texts can parallel and enhance the ‘Great Conversation’ among horizontal texts that lies at the heart of the humanities. Vergil’s ‘Isaiah acrostic’ – the great disruptive event of my intellectual life – participates in an intertextual conversation involving snakes, desire, and (im)mortality that ultimately traces back to the most consequential of biblical stories: the serpentine seduction of Eve.

One of the more fascinating parts of my journey has been getting to know the dipsas, a snake whose name comes from the Greek for ‘thirsty’ (as in ‘dipsomaniac’). This unsavoury critter, which appears frequently in ancient literature and material culture, was thought to experience unquenchable thirst itself and to induce that state in its victims. A Greek magical amulet, apparently intended to aid in human fertility by reducing excess uterine blood, pictures two snakes flanking an altar and bears the inscription ‘Dipsas-Tantalus, drink blood!’

Tantalus (source of ‘tantalise’) is the sinner punished in the underworld with unending hunger and thirst, as fruit and water constantly recede just out of his reach. Though there is some scholarly disagreement about how to interpret dipsas here – it could be referring to the snake, or it could be describing Tantalus as ‘thirsting’ – literary evidence suggests that Tantalus and the dipsas are closely connected, and that both are associated with sexual desire and sexual morbidity.

This is certainly true of the dipsas in Roman poetry. My first encounter with the dipsas was actually in the bedroom of Ovid’s girlfriend in the Amores. Here, ‘Dipsas’ is the name given to one of the stock figures in Roman elegy, the aged, drunken procuress (or lena), who spends most of the elegy instructing her young charge in how to be a tease and squeeze more money out of her clients. Ovid ends the poem with a curse activating the etymology of her name:

May the gods give you no home and an impoverished old age,

and long winters, and perpetual thirst.

The association of sexual desire with unquenchable thirst, and sometimes with snakes, is in fact an Ovidian leitmotif. In a hilarious dirge lamenting the poet’s impotence despite the proximity of his extremely desirable girlfriend, he compares himself to Tantalus, ‘thirsting in the middle of the waves’. Ovid’s masterpiece, the Metamorphoses, depicts a plague whose symptoms bear a suspicious resemblance to lovesickness – fever, blushing, insomnia, shortness of breath, and insatiable thirst – caused by snakes infecting springs and lakes.

This snake, so entwined in ancient literature and material culture, plays an essential role in the Vergilian acrostic

Later authors pick up on this connection as well. In Lucan’s Civil War epic, when Aulus, a soldier in the army of the Stoic hero Cato, is bitten by a dipsas in the Libyan desert, his symptoms again recall the imagery of lovesickness:

Look, the poison enters silently, and the devouring fire

gnaws his marrow and kindles his insides with wasting heat.

The Greek satirist Lucian, apparently drawing upon the Lucan passage, describes a Libyan statue of a dipsas victim:

For on [the monument] had been carved a man, as they depict Tantalus in paintings, standing in a lake and reaching out for the water to drink from it, and that wild beast – the dipsas – which had clung to him and twined around his foot.

Though the piece ends on a humorous note, likening these insatiable cravings to Lucian’s own wish to converse with his friends, it clearly establishes the association of the dipsas with various forms of human desire. This bizarre and terrifying snake, so entwined in ancient literature and material culture, will have an essential role to play in the Vergilian acrostic.

Nicander, a Greek poet of the 2nd century BCE, is not exactly a household name, and for good reason. His compendious didactic poems about snakes, other poisonous creatures and antidotes are hardly congenial to modern tastes. His older editors complained that he had little poetic talent, knew little about his subject matter, and brings little pleasure to his readers. Though scholars have recently begun to show the witty sophistication with which he transforms his literary predecessors, I must confess that I find reading him in Greek rather tedious: he’s short on story, and there are many lines where I have to look up every word, only to find I don’t know what half of them mean in English either. Nevertheless, I have lately come to realise that he is a crucial link in the chain connecting some of the Western tradition’s most important texts.

Of the many, many snakes he describes, along with the usually revolting effects their bites have on the human body, two stand out. One is the viper, from the Latin for ‘viviparous’ (live-young-bearing). This serpent has the amiable quality of biting off her mate’s head while he is impregnating her, but she gets her comeuppance when her young eat their way out of her womb. Human terms like ‘bedmate’ and ‘vengeance’ associate this phenomenon with the murderous family dysfunction of Greek tragedies. The other snake is our friend the dipsas. Nicander introduces these two species right after a snake simply called ‘The Female’, which gives a clue about what he is up to.

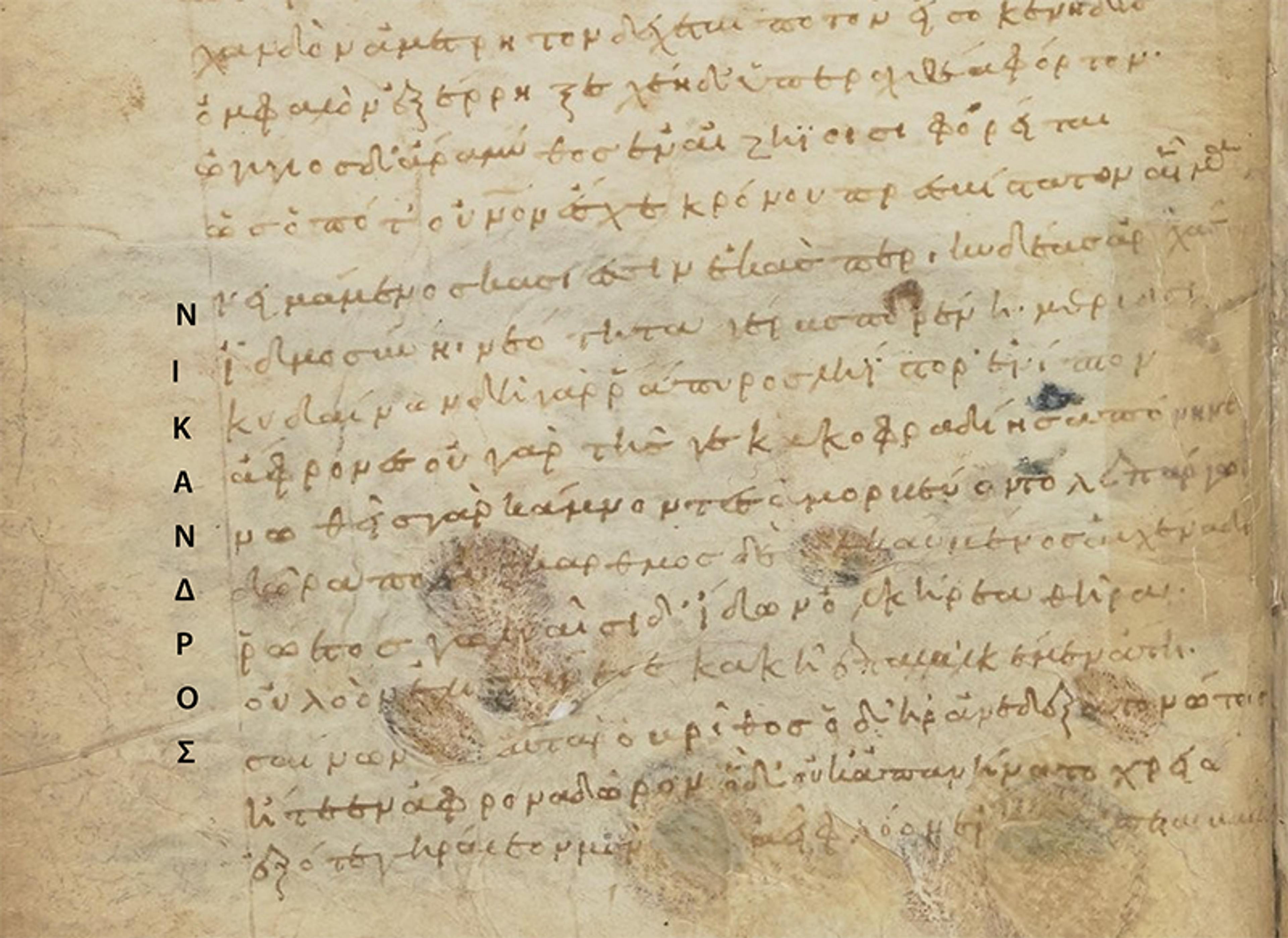

Nicander’s second and final dipsas passage tells us explicitly that it looks like the female viper. This episode is the poem’s most striking, both because it relates a highly significant story and because it contains an indisputably intentional acrostic of the poet’s own name. He begins by describing some graphic symptoms of a dipsas bite:

Above all, the form of the dipsas will always be similar to the viper,

the smaller one [ie, the female], and the doom of death will come more swiftly

to those whom this fearful snake assails: indeed, its slender tail,

always somewhat dark, gets black at the end;

and at its bite, the heart is utterly enflamed, and all around with fever

the parched lips wither with scorching thirst;

but he [the victim], like a bull bending over a river,

with gaping mouth takes in measureless drink until his belly

bursts his navel and pours out the too-heavy load.

He then relates a ‘primeval myth’ with universal consequences:

ὠγύγιος δ’ ἄρα μῦθος ἐν αἰζηοῖσι φορεῖται,

ὡς, ὁπότ’ οὐρανὸν ἔσχε Κρόνου πρεσβίστατον αἷμα,

Νειμάμενος κασίεσσιν ἑκὰς περικυδέας ἀρχάς

Ιδμοσύνῃ νεότητα γέρας πόρεν ἡμερίοισι

Κυδαίνων· δὴ γάρ ῥα πυρὸς ληίστορ’ ἔνιπτον.

Αφρονες, οὐ μὲν τῆς γε κακοφραδίῃσ’ ἀπόνηντο·

Νωθεῖ γὰρ κάμνοντες ἀμορβεύοντο λεπάργῳ

Δῶρα· πολύσκαρθμος δὲ κεκαυμένος αὐχένα δίψῃ

Ρώετο, γωλειοῖσι δ’ ἰδὼν ὁλκήρεα θῆρα

Οὐλοὸν ἐλλιτάνευε κακῇ ἐπαλαλκέμεν ἄτῃ

Σαίνων· αὐτὰρ ὁ βρῖθος ὃ δή ῥ’ ἀνεδέξατο νώτοις

ᾔτεεν ἄφρονα δῶρον· ὁ δ’ οὐκ ἀπανήνατο χρειώ.

ἐξότε γηραλέον μὲν ἀεὶ φλόον ἑρπετὰ βάλλει

ὁλκήρη, θνητοὺς δὲ κακὸν περὶ γῆρας ὀπάζει·

νοῦσον δ’ ἀζαλέην βρωμήτορος οὐλομένη θήρ

δέξατο, καί τε τυπῇσιν ἀμυδροτέρῃσιν ἰάπτει.

A primeval myth is told among people,

that, when the eldest blood of Kronos [Zeus] held the sky,

[acrostic begins] having allotted to his brothers glorious realms far apart,

in his wisdom he gave Youth as a reward for mortals,

honouring them: for indeed they told on the stealer of fire [Prometheus].

Fools, they got no joy from it, because of their negligence:

for out of weariness they entrusted their gift to a stupid ass to carry.

Skipping along, his throat burning with thirst,

and seeing in its hole the dragging beast,

with terrible folly he begged that deadly one to help,

[acrostic ends] fawning: but he [the snake] asked the witless one for the load

he had taken on his back as a gift: and he [the ass] did not refuse the request.

From that time, the dragging serpent casts off its aged skin,

but evil old age attends mortals: and the destructive beast

received the parching thirst of the braying one, and imparts it with its feeble blows.

A section of Nicander’s Theriaca manuscript dating c11th century CE, illustrating his acrostic signature. Aeon/the BnF, Paris

Not only is Nicander marking his territory, so to speak, with his vertical signature, but he is also activating the meaning of his name: andros means ‘of man’, and nik- (as in ‘Nike’) means victory. Such Greek compounds are frequently ambiguous: nik-andros could signify either the victory of man or the victory over man. The latter is obviously more appropriate here, since the wily serpent has bamboozled humankind out of eternal youth.

Nicander associates it with the Genesis story: the implicit theme of the war between the sexes

Where did Nicander get this idea? The story was treated by a number of tragic, lyric and comic poets of the 6th and 5th centuries BCE. The earliest source we know for a tale about a snake thwarting man’s immortality is the Babylonian Epic of Gilgamesh, predating Nicander by a millennium or more, in which the hero, while taking a dip in a pool, has a plant called ‘Man Becomes Young in Old Age’ stolen from him by a snake. There was plenty of cross-fertilisation among the cultures of ancient Greece, Rome, Egypt and the Levant; the Bible itself, especially the stories about the early world, contains much recycled material. So it would be claiming too much to say that Nicander could only have derived his deceitful talking snake directly or exclusively from the Jews.

Nevertheless, one feature of Nicander’s version associates it more particularly with the Genesis story: the implicit theme of the war between the sexes. Since Greek andros means not just human but male human, as opposed to the unisex anthropos, NIKANDROS may also suggest the victory of woman over man. In Genesis 3, God pronounces judgment upon the serpent and the Woman who caused Man to fall:

The LORD God said to the serpent,

‘Because you have done this, cursed are you above all cattle, and above all wild animals; upon your belly you shall go, and dust you shall eat all the days of your life. I will put enmity between you and the woman, and between your seed and her seed; he shall bruise your head, and you shall bruise his heel.’

To the woman he said,

‘I will greatly multiply your pain in childbearing; in pain you shall bring forth children, yet your desire shall be for your husband, and he shall rule over you.’

Nicander’s dipsas is strongly associated with the female viper, who represents both pain (death, in fact) in childbearing and a dysfunctional relationship with her husband, in which she is the dominatrix. Furthermore, the symptoms of the dipsas’s bite – fever, parching thirst, and drinking until the fluid explodes out of one’s navel – sound suspiciously similar to those of the lovesickness depicted by Roman authors.

The coupling of viper and dipsas, especially right after the snake called ‘The Female’, suggests that Nicander was alert to the relationship between the Fall of Man and the war between the sexes. Though there are obviously some differences, it is plausible to suppose a genetic connection with the Genesis episode. The supremely learned poet would surely have been interested in – and eager to show off his knowledge of – this memorable Jewish story, available in his day in Greek translation, in which a talking snake plays a leading role.

In my article on Original Sin and Vergil’s Orpheus and Eurydice episode in the Georgics, my starting point was the acrostic ISAIA AIT, ‘Isaiah says’, in the context of a woman dying by snakebite. Orpheus’s new bride Eurydice, fleeing from her would-be rapist Aristaeus (to whom the Isaiah-like prophet Proteus is recounting the tale), encounters a huge water-snake. Several cue words point to the ‘huge’ acrostic, which lies ‘before the [metrical] feet’ of the hexameter and along the ‘banks’ of the poem:

illa quidem, dum te fugeret per flumina praeceps,

Immanem ante pedes hydrum moritura puella

Seruantem ripas alta non uidit in herba.

At chorus aequalis Dryadum clamore supremos

Implerunt montis; flerunt Rhodopeiae arces

Altaque Pangaea et Rhesi Mauortia tellus

Atque Getae atque Hebrus et Actias Orithyia.

Ipse caua solans aegrum testudine amorem

Te, dulcis coniunx, te solo in litore secum,

te ueniente die, te decedente canebat.

She, indeed, while she was fleeing you headlong by the stream,

a girl destined to die, did not see a [acrostic begins] huge water-snake

before her feet guarding the banks in the high grass.

But her sister-chorus of Dryads filled the high mountains

with a wail; the peaks of Rhodope wept,

and high Pangaea [‘All-Earth’] and the martial land of Rhesus,

and the Getae, and the Hebrus, and Attic Orithyia.

Orpheus himself, solacing his miserable love on a hollow lyre,

kept singing you [acrostic ends], sweet wife, you to himself on the lonely shore,

you with the coming, you with the departing day.

I argued that Eurydice, the ‘girl destined to die’, is a kind of Eve figure, killed by a snake and mourned by universal nature. What I did not know then – but came to realise thanks to another chance conversation, this time with Michael Reeve about his article ‘A Rejuvenated Snake’ (1996-7) – is that Vergil’s biblical acrostic alludes to Nicander’s. That is, Vergil was not only recalling the Genesis episode that brought death into the world, but recalling it through the lens of a Greek author who did the same – and expecting at least some of his learned readers to get both allusions. While this sort of ‘window reference’ is common for highly literate classical authors, the fact that the Bible is involved sheds new light on the highway between Athens and Jerusalem, suggesting that ancient non-Jewish readers’ access to and interest in the Septuagint may have been far greater than is commonly supposed.

A characteristic feature of window references is the ‘correction’ of one’s predecessors, and Vergil’s is no exception. For instance, he adds the water that the Greek poet strangely omits: why else would the ass have asked the dipsas to help him with his thirst unless the snake were, as Vergil has it, ‘guarding the banks’? Vergil corrects the name as well, calling his water-guarding snake hydrus, from the Greek for ‘water’, the opposite of dipsas, ‘thirsty’. Like Nicander and the Bible, Vergil implicitly depicts a battle of the sexes, but he inverts the roles and assigns the blame to men. Eurydice dies once fleeing from a rapist, and again when Orpheus makes the fatal mistake of looking back as he is leading her out of the underworld.

Vergil and Nicander show both similarities and differences in their divine rewards and punishments. In Nicander’s story, the god of the sky gives humankind a chance at eternal youth as a reward for our tattling on Prometheus, stealer of fire. In Vergil’s, the god of the underworld gives a human a chance to escape from his realm temporarily as a reward for Orpheus’ transcendently beautiful song. The stories diverge in that Nicander’s Man, weary from carrying the precious gift, entrusts it to the back of a foolish ass, who becomes a potent symbol of appetite in conflict with rational intelligence. Yet there is a certain similarity to Orpheus nonetheless: emotionally wearied by having Eurydice at his back, he foolishly and irrationally gratifies his desire to see her rather than delaying his gratification so as to save her.

I have argued that the story spanned by Nicander’s signature serpent alludes to the biblical Fall, and that Vergil in his Orpheus and Eurydice episode incorporates both Nicander and the Bible, signalling the allusion with a biblical acrostic of his own: ISAIA AIT. But that leaves a final question. Why is the dipsas, in particular, the star of Nicander’s Fall story, since all snakes renew their youth by shedding their skin?

Nicander’s association of the Fall with unslakable thirst, which we attempt to satisfy in ways that lead to our destruction, shows his insight into both the biblical narrative and the nature of evil. In the Jewish and Christian understanding, the constant result of our primordial separation from God – brought about by a malicious serpent – is an insatiable yearning for that lost communion, which the psalms and prophets frequently describe as thirsting for God: ‘As the deer longs for streams of water, so I long for you, O God.’ God promises that this thirst will be quenched: ‘Ho, everyone who thirsts, come to the waters.’ But there’s one exception. In the Edenic vision of God’s holy mountain, ‘The wolf and the lamb will feed together, and the lion will eat straw like the ox, but dust will be the serpent’s food.’ The serpent is the only animal left out of the party – just as God had promised in Genesis, ‘dust shall you eat, all the days of your life.’

Classical texts are enmeshed in a web of relationships that can surprise and invigorate, even after thousands of years

The perpetual thirst of Nicander’s dipsas is a logical consequence of that unsatisfying diet. The dipsas may be functionally immortal, but only at the price of eternal misery; imparting torturous thirst to others does not actually bring the beast any relief. Like the biblical serpent, its motivation is pure malice. As St Ambrose declared: ‘No one ever healed himself by hurting another.’ In the present age of electronic venom, absorbing that lesson from Nicander’s etiological tale could help us all.

Another reward of the humanities’ Great Conversation is the joy of seeing familiar words borrow the serpent’s power to ‘become young in old age’. It had simply never occurred to me that reading vertically might enhance my understanding of the horizontal narrative. Discovering this new dimension in Vergil and other ancient poets has both increased my appreciation of their genius and emphasised the benefit of learning the original languages, since acrostics vanish completely in translation. On the other hand, the potential importance of Jewish texts for classical authors is something that should be receiving more attention from all readers, scholars and students alike.

As Italo Calvino observed: ‘A classic is a book that has never finished saying what it has to say.’ Vergil was not only reading the Bible, but reading it through the eyes of a Greek author who used the biblical story to enrich his own – and both authors left vertical clues whose significance is only now coming to light. In tracing the biblical serpent’s acrostic tail, we see how classical texts are enmeshed in a dense web of relationships that can surprise and invigorate us, even after thousands of years. The eternally thirsty snake may symbolise evil’s contagion and ‘victory over man’. But it can also symbolise the contagious, unquenchable thirst of the humanities – and humans – for the truth and beauty ever ancient, ever new.