I regret everything. Decades-old decisions, things I said, things I didn’t say, opportunities I missed, opportunities I took, recent purchases, non-purchases, returns. I turn all of these things over in my mind and examine them for clues — to what, I’m not sure. All I know is that very little of what I do or fail to do escapes the constant churn of revision. It’s just the way I process experience: sceptically, and in retrospect. It’s like being a time-traveller, only instead of going back to Ancient Rome or the French Revolution, I return again and again to the traumatic sites of my own fateful (or not so fateful) forks in the road. Some people see this as self‑flagellation; I tend to think of it as a lifelong effort to reconcile the possible with the actual — a getting to know the real me. After all, as they say, we’re defined by our choices.

When I was six years old, I pulverised a friend’s brand-new Etch A Sketch. Actually, he wasn’t my friend — our mothers were friends, I didn’t know him all. He was a little bit older than me — maybe seven or eight — and I found him aloof and intimidating. He lived in an enormous modern house made of glass and concrete, with an exterior staircase that led to a balcony overlooking a terrace and pool. We were visiting Lima, where my Peruvian parents were from, from suburban New Jersey, and I felt like a fish out of water — shy, awkward, foreign, weird. At some point, I broke away from the other kids and went up to the balcony to be alone with the Etch A Sketch, which the boy had received for Christmas a few days earlier. Alone, I was gripped by the sudden urge to balance the Etch A Sketch on the balcony railing. Even as the idea was forming in my mind, I knew that its risks far outweighed its dubious rewards, and that I’d live to regret it. I was still thinking these thoughts as I watched the Etch A Sketch fall through the air and land in one piece with a sickening crunch. When I picked it up, it made a sound like a maraca. The knobs moved but no lines appeared on the screen. I then placed the Etch A Sketch carefully on a nearby chair, went to find my mother, and told her I had a headache and wanted to go home.

Remorse, it seems to me, would have been the more appropriate response to having destroyed my young host’s shiny new present from Santa, but that would have involved a degree of empathy that I’m ashamed to admit I didn’t feel for him. Somewhere deep down, I interpreted his cool self-possession as contemptuous indifference or outright disdain, and in enacting my tiny rebellion, I succeeded only in manifesting my worst fears about myself. In my fit of alienation and insecurity, I’d turned myself into the person I thought he thought I was: The weirdo who broke his new toy. And I’d made sure he’d remember me that way forever.

There’s a particular disdain for regret in US culture. It’s regarded as self-indulgent and irrational — a ‘useless’ feeling. We prefer utilitarian emotions, those we can use as vehicles for transformation, and closure. ‘Dwelling’, we tend to agree, gets you nowhere. It just leads you around in circles.

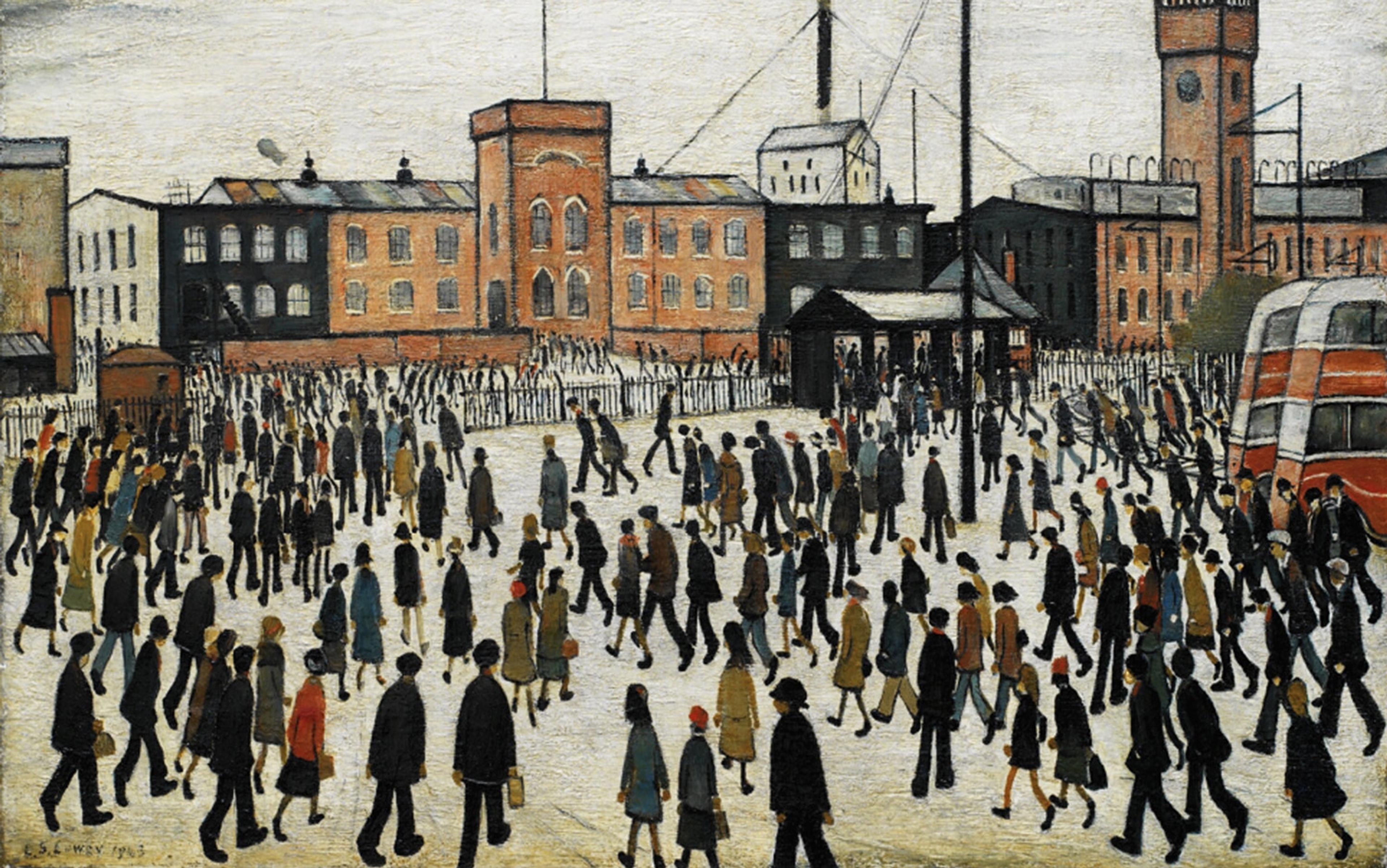

Regret is so counter to the pioneer spirit — with its belief in blinkered perseverance, and dogged forward motion — it’s practically un-American. In the US, you keep your squint firmly planted on the horizon and put one foot in front of the other. There’s something suspiciously female, possibly French, about any morbid interiority.

Best, then, to treat the past like an overflowing closet: just shut the door and walk away. ‘What’s done is done,’ we say. ‘It is what it is.’ ‘There’s no use crying over spilt milk.’

Sometimes, the prevalence of this point of view makes me feel regret toward my tendency toward regret. It’s hard not to feel bad when your way of processing experience is routinely pathologised, or dismissed offhand as whiny, weak, and useless. As I write this, I regret writing it because I fear it makes me sound more neurotic than I really am. At the same time, I worry that it makes me sound exactly as neurotic as I actually am, and I regret not having done a better job of keeping this under wraps. I regret regretting things all the time, because surely I could be putting my imagination to better use. What’s more, I regret that I’m compelled to talk about my regrets, not just in therapy, but at dinner, at the playground, on the phone, and in print. I regret these things in part because I’m acutely aware of how my regrets are perceived when I express them. What I want are deep explorations of parallel universes and alternative outcomes. But what I get in return are sad-eyed smiles, gentle pats on the arm, and the occasional rousing pep talk, which is never what I’m after.

The assumption is that these ruminations stem from a flaw in my character, or an unresolved trauma, or some questionable behaviourist conditioning. It’s a neurobiological glitch, maybe, or a bad habit. And all of these might apply, but I also think I’m driven by a combination of pragmatism and curiosity. Whenever I come up against a problem, or find myself plagued by questions I can’t answer, my impulse is to lift up the hood of my day-to-day denial and complacency and dive into the intricate circuitry of my past in search of whatever minor gasket malfunction sparked the powder train that eventually blew up the spacecraft. I guess in some way, I’ve come to think of regret as a deductive game that, although it’s almost never fun, will eventually unlock all of life’s mysteries. Is this what I intended to do? Could I have predicted this outcome? How did I get here?

The idea that maybe nothing happens for a reason is deeply unsettling to many

In the fall of my senior year of high school, my dad and I flew from Madrid, where we lived, to Boston for college interviews. My dad’s career was going off the rails at the time, but he was feeling hopeful and expansive, so when the airline misplaced his luggage, we headed straight for Brooks Brothers and then went out for lobster. My first college interview, which also happened to be my first interview of any kind, ever, was at Harvard. It hadn’t occurred to me to do anything to prepare for it, much less to try to get a sense of what to expect.

As it happened, the person who interviewed me had been a teacher at my high school in Madrid 20 years earlier. He knew my principal as well as several veteran teachers. We talked about Spain’s transition to democracy after Franco, about the way the country seemed to wake up after a deep 40-year sleep. We talked about dress codes in restaurants and porn on TV. As the interview was ending, I was suddenly struck by the feeling that I’d messed up. I’d frittered away the interview making clever observations about the politics of shorts. And even though the interviewer seemed encouraging, I decided, when it came time to work on the application form, to save my dad the $50 application fee. And neither one of my parents had anything to say about it. Yes, I could have applied and gotten rejected like everyone else. But if I had, I probably wouldn’t have blown my interview 20 years later, when I was a finalist for a fellowship. But I guess I’ll never know that, either.

Pop psychology books on the subject of regret offer easy-to-follow plans on how to eradicate it, like a virus or a muffin top. They dismiss it with titles such as Woulda, Coulda, Shoulda: Overcoming Regrets, Mistakes, and Missed Opportunities (1989), No Regrets: A 10-Step Program for Living in the Present and Leaving the Past Behind (2004), and One Month to Live: 30 Days to a No-Regrets Life (2008). Regret isn’t just seen as antithetical to reason, it’s spiritually transgressive as well. Sayings such as ‘Everything happens for a reason’ inherently condemn the sort of nihilist relativism that might experience regret as proof of the random meaninglessness of life. Regret is sinful, a direct rebuke to the existence of a God that knows what he’s doing, and cares.

What these two world views, pop psychology and religion, have in common is a deep-seated need for meaning and order, for a system or a narrative that makes sense of the world. The idea that maybe nothing happens for a reason is deeply unsettling to many people. For the rationalist, regretting past events or actions is tantamount to admitting to the terrifying possibility that failing is as easy as knocking over a glass. Goal-based decision-making gives structure to what would otherwise be a series of random events, and accomplishing those goals gives the illusion of meaning. The idea that it’s always preferable to keep your eyes trained on the future, to look on the bright side, and to let go and let God take over is deeply ingrained in both rational and religious world views.

And yet something about these attitudes toward regret rankles me. They strike me not just as inhumanly opposed to emotion, but also as anti-intellectual.

In her book Regret: The Persistence of the Possible (1993), the poet and psychologist Janet Landman argues that our views on regret are shaped in large part by decision theory as it relates to the theory of economic choice. In this framework, the past must be repudiated in rational decision-making because decision theory assumes that the person making the decision is rational, informed, and able to make accurate calculations. ‘If conflicting values and demands are resolvable by the astute application of cost-benefit analysis,’ Landman writes, describing this economic idea in a nutshell, ‘then regret’ — which is both counterfactual (it dwells on what might have been, but wasn’t) and emotional (these imagined alternative scenarios spark feelings) — ‘is simply uncalled for.’

People feel they need to deny regret — deny failure — in order to stay in the game

Our discomfort with regret, she writes, reflects an ‘existential discomfort with the limits of our personal control’. The idea that human experience and behaviour can best be understood and optimised by reducing it to data has become only more entrenched since Landman wrote her book. It gets easier every day to project a future without regret; to be the best, most optimal people we can be today, so that we can look back without ambivalence. Life is not mysterious, it’s mathematics. All we have to do is track our productivity, our spending, our steps, our calorie intake. All we have to do is count our friends and likes and follows. The illusion of control that these tools grant us over every aspect of our lives is powerful. There is always something we can do today to avoid regret tomorrow. To admit regret is to admit to a previous failure of self-control. ‘In the reigning economic models of decision, human beings are “calculating machines” who decide their preferences based on calculations of utilities and probabilities,’ Landman writes. ‘We deny regret in part to deny that we are now or have ever been losers.’

In a culture that believes winning is everything, that sees success as a totalising, absolute system, happiness and even basic worth are determined by winning. It’s not surprising, then, that people feel they need to deny regret — deny failure — in order to stay in the game. Though we each have a personal framework for looking at regret, Landman argues, the culture privileges a pragmatic, rationalist attitude toward regret that doesn’t allow for emotion or counterfactual ideation, and then combines with it a heroic framework which equates anything that lands short of the platonic ideal with failure. In such an environment, the denial of failure takes on magical powers. It becomes inoculation against failure itself. To express regret is nothing short of dangerous. It threatens to collapse the whole system.

In starting to lay out the possible uses of regret, Landman quotes William Faulkner. ‘The past,’ he wrote in 1950, ‘is never dead. It’s not even past.’ Great novels, Landman points out, are often about regret: about the life-changing consequences of a single bad decision (say, marrying the wrong person, not marrying the right one, or having let love pass you by altogether) over a long period of time. Sigmund Freud believed that thoughts, feelings, wishes, etc, are never entirely eradicated, but if repressed ‘[ramify] like a fungus in the dark and [take] on extreme forms of expression’. The denial of regret, in other words, will not block the fall of the dominoes. It will just allow you to close your eyes and clap your hands over your ears as they fall, down to the very last one.

Not surprisingly, it turns out that people’s greatest regrets revolve around education, work, and marriage, because the decisions we make around these issues have long-term, ever-expanding repercussions. The point of regret is not to try to change the past, but to shed light on the present. This is traditionally the realm of the humanities. What novels tell us is that regret is instructive. And the first thing regret tells us (much like its physical counterpart — pain) is that something in the present is wrong.

Some years ago, I was working at a job I liked when I was approached about another, higher-paying job. In fact, it paid so much more that I was convinced my current job would never match it. I don’t know what I based this knowledge on, having never had a similar experience, but I did. The process of interviewing for the new job was secretive and stressful, and it made it hard to get advice from people who might have helped. When I got the offer, I did get advice from someone I knew in finance. ‘Don’t base your decision on the money,’ she said. ‘Decide where you’d rather be and don’t try to start a bidding war. In the end, you’ll be resented for it.’ This advice came from someone who made more money than I ever would, for whom the money — beyond a certain a level — became theoretical. But it didn’t apply to my situation. While the money wasn’t entirely the point, it was unignorable.

I took the job, declined to listen (embarrassingly) to counteroffers from my employer, which caused hard feelings, and immediately regretted it. At the end of my first day, feeling as if I’d entered the Twilight Zone, I called my friend from the car, very upset. ‘I made a huge mistake!’ I said. She took command. ‘It’s too late now,’ she said. ‘You made your decision. What’s done is done.’ It took a couple of years for me to realise that this was the second bit of bad advice I’d received in relation to this decision. Both stemmed from a total rejection of things that are hard to quantify, and a slavish belief in the primacy of quick, decisive action over ambivalence, ambiguity, and mixed feelings.

It’s in this privileging of reason unfettered by emotion, this thinking of people as ‘calculating machines’ that Landman suggests we’ve gone all wrong. The problem lies in clinging to absolutes and falling for false dichotomies. Sometimes, our assessment of reality is faulty, or obsolete, or weirdly ideological, or based on false dichotomies such as reason vs emotion, or the past vs the present.

Mixed feelings are not only what make us human, they’re what make us truly rational. They help us arrive at complicated truths by way of a dialectic process. Rather than deny regret, we should embrace ambivalence. We should strive for an ideal — that is, behave as if it’s possible for an absolute ideal to exist — while remembering that it doesn’t, that in fact outcomes are random, and that all possibilities exist simultaneously.