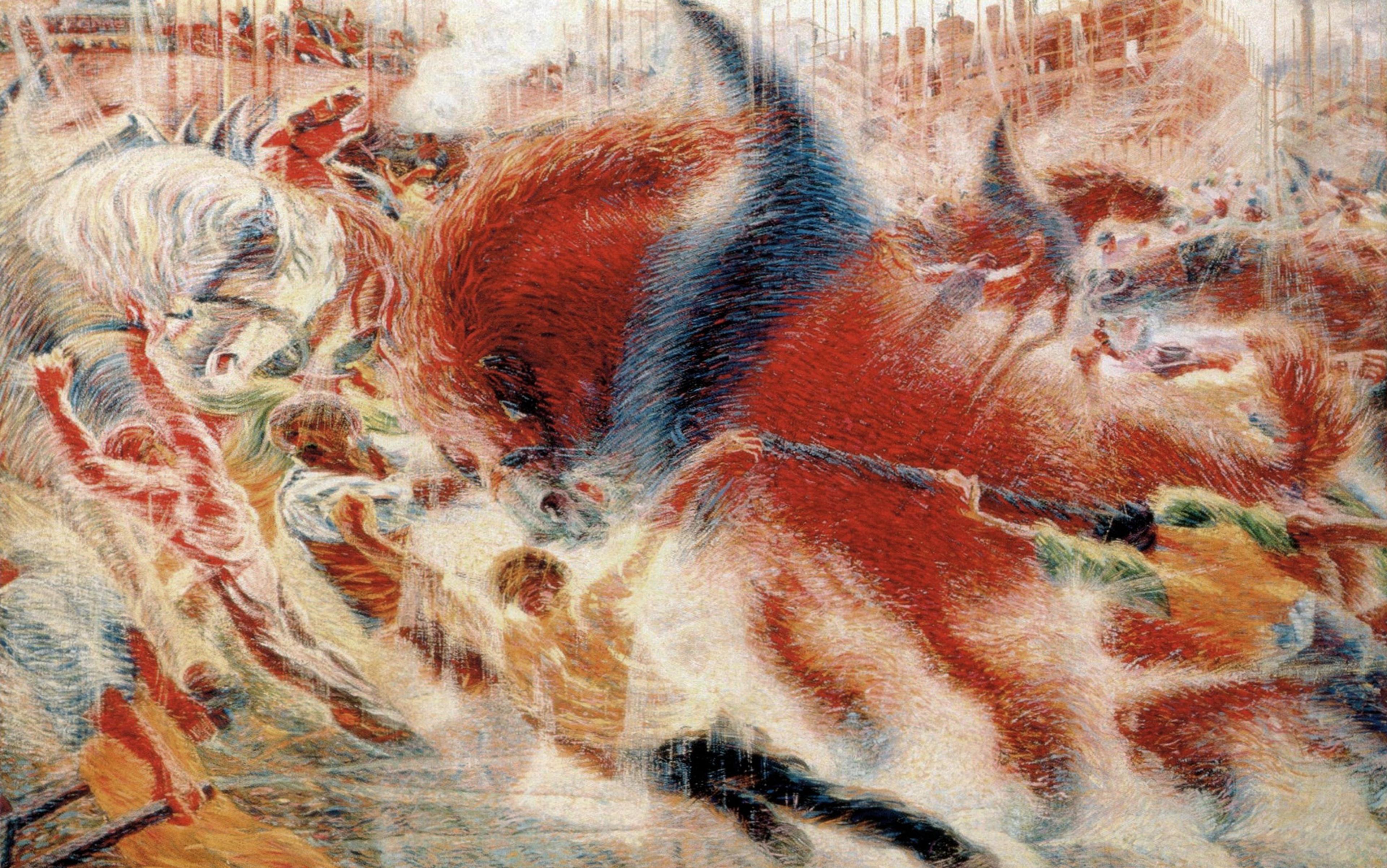

In the summer of 2008, police arrived at a caravan in the seaside town of Aberporth, west Wales, to arrest Brian Thomas for the murder of his wife. The night before, in a vivid nightmare, Thomas believed he was fighting off an intruder in the caravan – perhaps one of the kids who had been disturbing his sleep by revving motorbikes outside. Instead, he was gradually strangling his wife to death. When he awoke, he made a 999 call, telling the operator he was stunned and horrified by what had happened, and unaware of having committed murder.

Crimes committed by sleeping individuals are mercifully rare. Yet they provide striking examples of the unnerving potential of the human unconscious. In turn, they illuminate how an emerging science of consciousness is poised to have a deep impact upon concepts of responsibility that are central to today’s legal system.

After a short trial, the prosecution withdrew the case against Thomas. Expert witnesses agreed that he suffered from a sleep disorder known as pavor nocturnus, or night terrors, which affects around one per cent of adults and six per cent of children. His nightmares led him to do the unthinkable. We feel a natural sympathy towards Thomas, and jurors at his trial wept at his tragic situation. There is a clear sense in which this action was not the fault of an awake, thinking, sentient individual. But why do we feel this? What is it exactly that makes us think of Thomas not as a murderer but as an innocent man who has lost his wife in terrible circumstances?

Automatism implies that the accused person had no control over his actions, that he acted like a runaway machine

Our sympathy can be understood with reference to laws that demarcate a separation between mind and body. A central tenet of the Western legal system is the concept of mens rea, or guilty mind. A necessary element to criminal responsibility is the guilty act — the actus reus. However, it is not enough simply to act: one must also be mentally responsible for acting in a particular way. The common law allows for those who are unable to conform to its requirements due to mental illness: the defence of insanity. It also allows for ‘diminished capacity’ in situations where the individual is deemed unable to form the required intent, or mens rea. Those people are understood to have control of their actions, without intending the criminal outcome. In these cases, the defendant may be found guilty of a lesser crime than murder, such as manslaughter.

In the case of Brian Thomas, the court was persuaded that his sleep disorder amounted to ‘automatism’, a comprehensive defence that denies there was even a guilty act. Automatism is the ultimate negation of both mens rea and actus reus. A successful defence of automatism implies that the accused person had neither awareness of what he was doing, nor any control over his actions. That he was so far removed from conscious awareness that he acted like a runaway machine.

The problem is how to establish if someone lacks a crucial aspect of consciousness when he commits a crime. In Thomas’s case, sleep experts provided evidence that his nightmares were responsible for his wife’s death. But in other cases, establishing lack of awareness has proved more elusive.

It is commonplace to drive a car for long periods without paying much attention to steering or changing gear. According to Jonathan Schooler, professor of psychology at the University of California, Santa Barbara, ‘we are often startled by the discovery that our minds have wandered away from the situation at hand’. But if I am unconscious of my actions when I zone out, to what degree is it really ‘me’ doing the driving?

This question takes on a more urgent note when the lives of others are at stake. In April 1990, a heavy-goods driver was steering his lorry towards Liverpool in the early evening. Having driven all day without mishap, he began to veer on to the hard shoulder of the motorway. He continued along the verge for around half a mile before he crashed into a roadside assistance van and killed two men. The driver appeared in Worcester Crown Court on charges of causing death by reckless driving. For the defence, a psychologist described to the court that ‘driving without awareness’ might occur following long, monotonous periods at the wheel. The jury was sufficiently convinced of his lack of conscious control to acquit on the basis of automatism.

The argument for a lack of consciousness here is much less straightforward than for someone who is asleep. In fact, the Court of Appeal said that the defence of automatism should not have been on the table in the first place, because a driver without ‘awareness’ still retains some control of the car. None the less, the grey area between being in control and aware on the one hand, and in control and unaware on the other, is clearly crucial for a legal notion of voluntary action.

If we accept automatism then we reduce the conscious individual to an unconscious machine. However, we should remember that all acts, whether consciously thought-out or reflexive and automatic, are the product of neural mechanisms. For centuries, scientists and inventors have been captivated by this notion of the mind as a machine. In the 18th century, Henri Maillardet, a Swiss clockmaker, built a remarkable apparatus that he christened the Automaton. An intricate array of brass cams connected to a clockwork motor made a doll produce beautiful drawings of ships and pastoral scenes on sheets of paper, as if by magic. This spookily humanoid machine, now on display at the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia, reflects the Enlightenment’s fascination with taming and understanding the mechanisms of life.

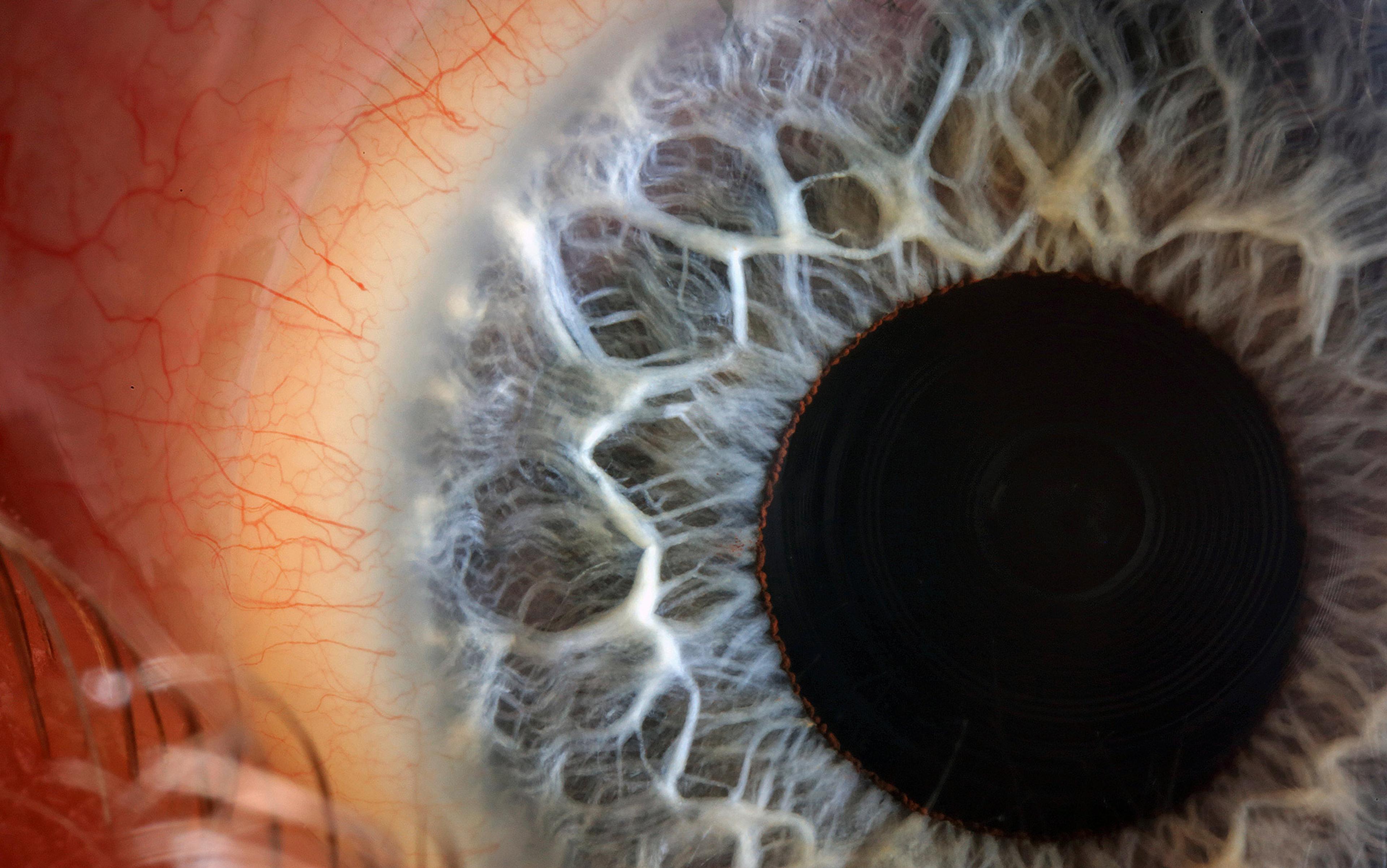

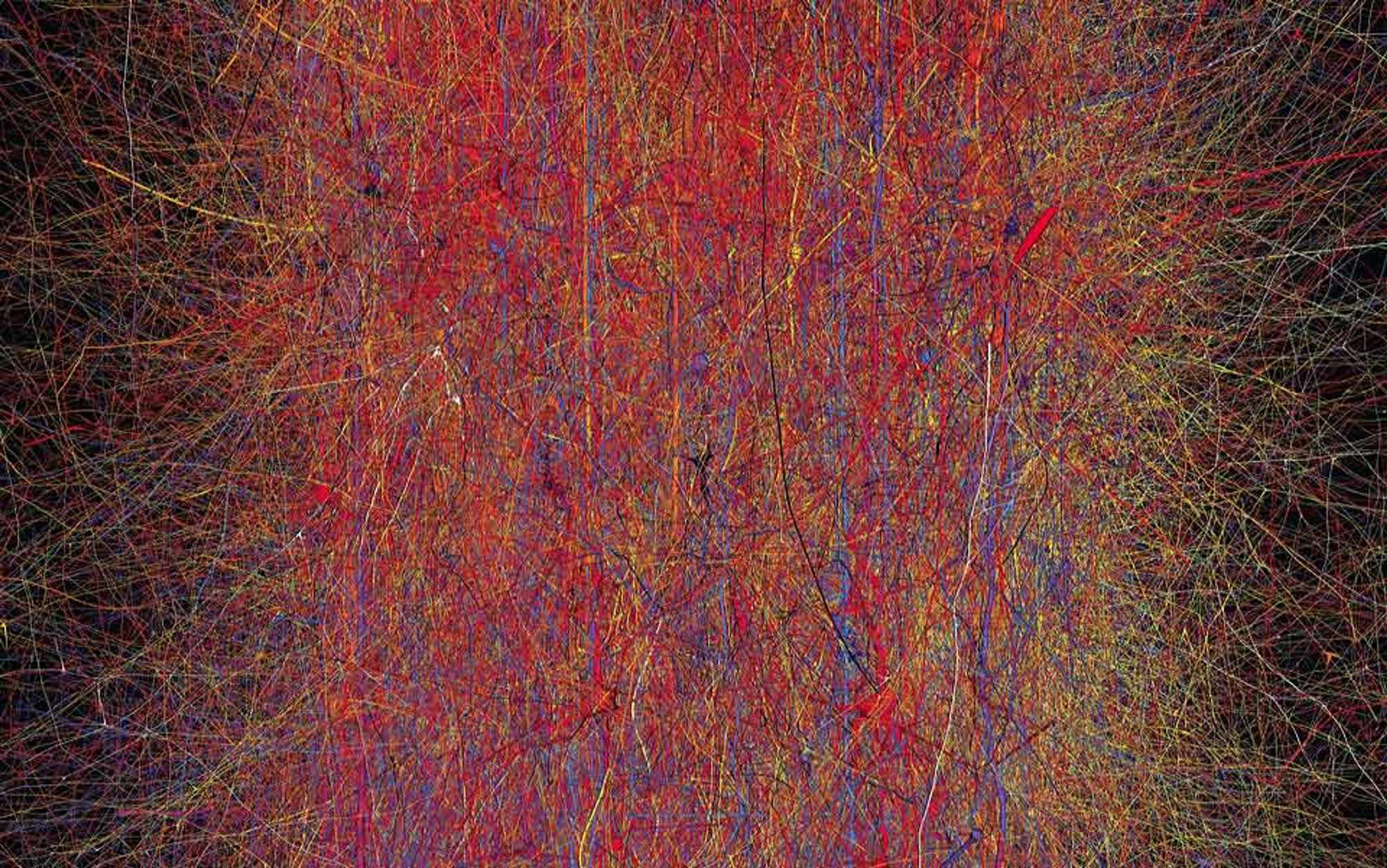

Modern neuroscience takes up where Maillardet left off. From the pattern of chemical and electrical signaling between around 85 billion brain cells, each of us experiences the world, makes decisions, daydreams, and forms friendships. The mental and the physical are two sides of the same coin. The unsettling implication is that, by revealing a physical correlate of a conscious state, we begin to treat the individual not as a person but as a machine. Perhaps we are all ‘automata’, and our notions of free choice and taking responsibility for our actions are simply illusions. There is no ghost in the machine.

Under the influence of alcohol, people become more likely to daydream and less likely to catch themselves doing so

In his book Incognito (2011), David Eagleman argues that society is poised to slide down the following slippery slope. Measurable brain defects already buy leniency for the defendant. As the science improves, more and more criminals will be let off the hook thanks to a fine-grained analysis of their neurobiology. ‘Currently,’ Eagleman writes, ‘we can detect only large brain tumours, but in 100 years we will be able to detect patterns at unimaginably small levels of the microcircuitry that correlate with behavioral problems.’ On this view, responsibility has no place in the courtroom. It is no longer meaningful to lock people up on the basis of their actions, because their actions can always be tied to brain function.

While it is inevitable that defence teams will look towards neuroscientific evidence to shift the balance in favour of a mechanistic, rather than a personal, interpretation of criminal acts. But we should be wary of attempts to do so. If every behaviour and mental state has a neural correlate (as surely it must), then everything we do is an artifact of our brains. A link between brain and behaviour is not enough to push responsibility out of the courtroom. Instead we need new ways of thinking about responsibility, and new ways to conceptualise a decision-making self.

Responsibility does not entail a rational, choosing self that floats free from physical processes. That is a fiction. Even so, demonstrating a link between criminal behaviour and conscious (or unconscious) states of the brain changes the legal landscape. Consciousness is, after all, central to the legal definition of intent.

In the early ’70s, the psychologist Lawrence Weiskrantz and the neuropsychologist Elizabeth Warrington discovered a remarkable patient at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London. This patient, known as DB, had sustained damage to the occipital lobes (towards the rear of the brain), resulting in blindness in half of his visual field. Remarkably, DB was able to guess the position and orientation of lines in his ‘blind’ hemifield. Subsequent studies on similar patients with ‘blindsight’ confirmed that these responses relied on a neural pathway quite separate from the one that usually passes through the occipital lobes. So it appears that visual consciousness is selectively deleted in blindsight. At some level, the person can ‘see’ but is not aware of doing so.

Awareness and control, then, are curious things, and we cannot understand them without grappling with consciousness itself. What do we know about how normal, waking consciousness works? Hints are emerging. Studies by Stanislas Dehaene, professor of experimental cognitive psychology at the Collège de France in Paris, have revealed that a key difference between conscious and unconscious vision is activity in the prefrontal cortex (the front of the brain, particularly well-developed in humans). Other research implies that consciousness emerges when there is the right balance of connectivity between brain regions, known as the ‘information integration’ theory. It has been suggested that anesthesia can induce unconsciousness by disrupting the communication between brain regions.

Some fear that an increased understanding of consciousness will dissolve our sense of personal responsibility

Just as there are different levels of intent in law, there are different levels of awareness that can be identified in the lab. Despite being awake and functioning, one’s mind might be elsewhere, such as when a driver zones out or when a reader becomes engrossed. A series of innovative experiments have begun to systematically investigate mind-wandering. When participants zone out during a repetitive task, activity increases in the ‘default network’, a set of brain regions previously linked to a focus on internal thoughts rather than the external environment. Under the influence of alcohol, people become more likely to daydream and less likely to catch themselves doing so. These studies are beginning to catalogue the influences and mechanisms involved in zoning out from the external world. With their help we can refine the current legal taxonomy of mens rea and put legal ideas such as recklessness, negligence, knowledge and intent on a more scientific footing.

An increased scientific understanding of consciousness might one day help us to determine the level of intent behind particular crimes and to navigate the blurred boundary between conscious decisions and unconscious actions. At present, however, we face serious obstacles. Most studies in cognitive neuroscience rely on averaging together many individuals. A group of individuals allows us to understand the average, or typical, brain. But it does not follow that each individual in the group is typical. And even if this problem were to be overcome, it would not help us to adjudicate cases in which normal waking consciousness was intact, but happened to be impaired at the time of the crime.

Nonetheless, the brain mechanisms underpinning different levels of consciousness are central to a judgment of automatism. Without consciousness, we are justified in concluding that automatism is in play, not because consciousness itself is not also dependent on the brain, but because consciousness is associated with actions worth holding to a higher moral standard. This perspective helps to arrest the slide down Eagleman’s slippery slope. Instead of negating responsibility, neuroscience has the potential to place conscious awareness on an empirical footing, allowing greater certainty about whether a particular individual had the capacity for rational, conscious action at the time of the crime.

Some worry that an increased understanding of consciousness and voluntary action will dissolve our sense of personal responsibility and free will. In fact, neurological self-knowledge could have the opposite effect. Suppose we discover that the brain mechanisms underpinning consciousness are primed to malfunction at a particular time of day, say 7am. Up until this discovery, occasional slips and errors made around this time might have been put down to chance. But now, armed with our greater understanding of the fragility of consciousness, we would be able to put in place counter-measures to make major errors less likely. For Brian Thomas, a greater understanding of his sleep disorder might have allowed him to control it. He had stopped taking his anti-depressant medication when he was on holiday, because he believed it made him impotent. This might have contributed to the night terrors that caused him to strangle his wife.

Crucially, increased self-knowledge often percolates through to laws governing responsible behaviour. A diabetic who slips into a coma while driving is held responsible if the coma was the result of poor management of a known diabetic condition. Someone committing crimes while drunk is held to account, so long as they are responsible for becoming drunk in the first place. A science of consciousness illuminates the factors that lead to unconsciousness. In reconsidering the boundary between consciousness and automatism we will need to take into account the many levels of conscious and unconscious functioning of the brain.

Our legal system is built on a dualist view of the mind-body relationship that has served it well for centuries. Science has done little to disrupt that until now. But neuroscience is different. By directly addressing the mechanisms of the human mind, it has the potential to adjudicate on issues of capacity and intent. With a greater understanding of impairments to consciousness, we might be able to take greater control over our actions, bootstrapping ourselves up from the irrational, haphazard behaviour traditionally associated with automata. Far from eroding a sense of free will, neuroscience may allow us to inject more responsibility than ever before into our waking lives.

For references to the scientific research discussed in this essay, see Steve Fleming’s blog The Elusive Self.