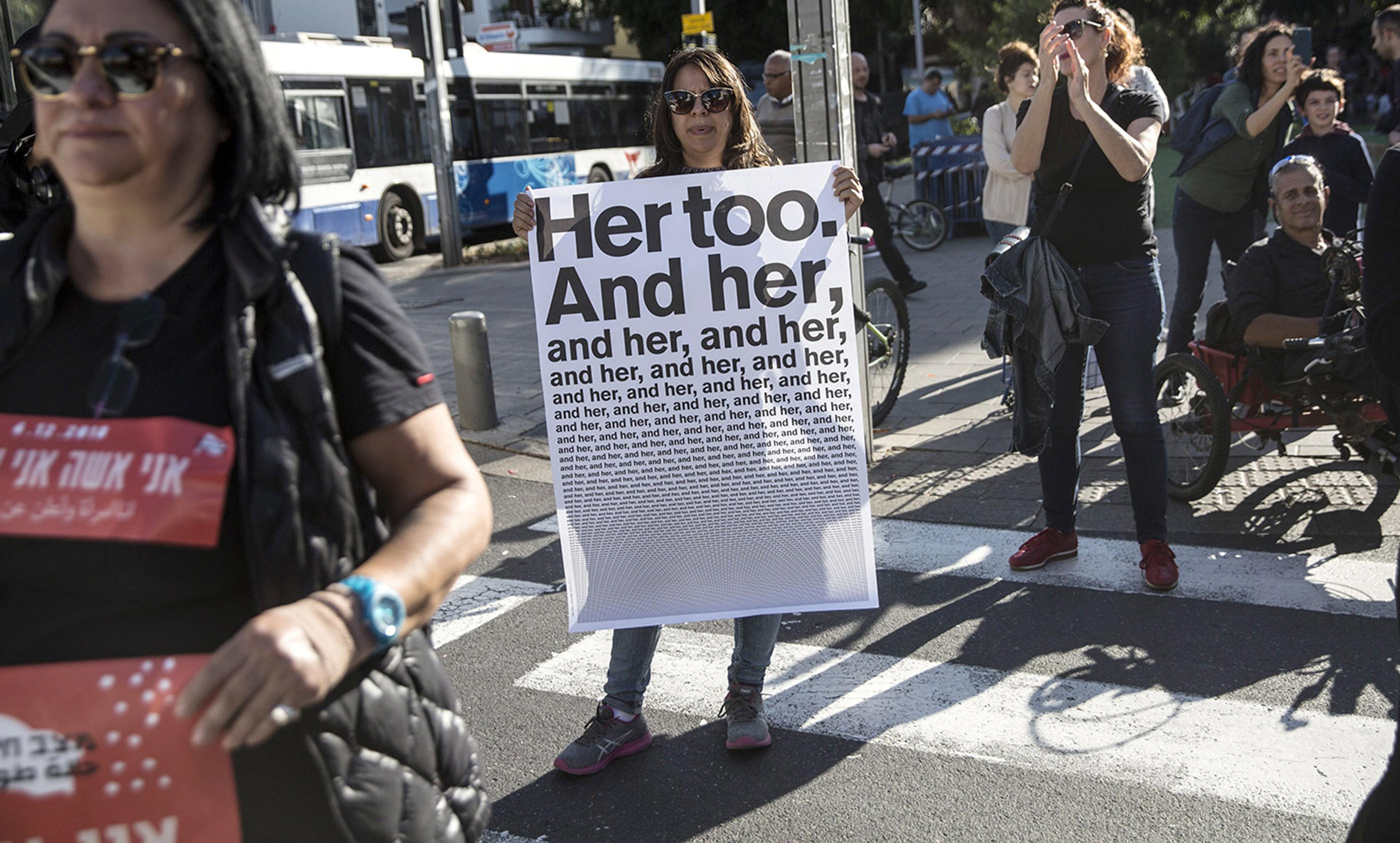

Unusually, the British government issued an apology for abuses during the so called Mau Mau uprising in Kenya: ‘The British government recognises that Kenyans were subjected to torture and other forms of ill-treatment at the hands of the colonial administration.’ Photo by Rex

From childhood, we are taught that our actions can cause harm. In our personal lives, we know that the health and integrity of our relationships are fragile. When harm has been done, it is as if the relationship walks with a stone in its shoe, ever stumbling a little. If it is ever to amble along nicely again, the person who committed the wrongful act must face those she hurt, acknowledge her responsibility, and apologise.

What about when nations do harm? Can national apologies accomplish anything and, if so, how?

The transformative power of apologies, both individual and collective, lies in their ability to alter identity and re-direct time. When I apologise, I assume two conflicting identities. I acknowledge that I am the one who committed the wrong, but I also enact a new identity as a person who condemns that wrong, and would not repeat it. In a similar double movement, when I apologise, I move back in time so that the future will not remain stuck in that past. If we want the future to have the exhilarating quality of the ‘not-yet’, and to be be open to new possibilities, we need to turn around and face the wreckage we have left in our wake. We need to apologise for our role in the destruction.

Words alone are not sufficient. For an apology to be effective, the wrongdoer must experience authentic regret, take actions to compensate for the loss, and promise not to repeat the wrong. In other words, the act of speech, while necessary, must be accompanied by acts of the hands, heart and mind. Nevertheless, as the philosopher Moses Maimonides taught some 800 years ago, repentance can do its transformative work only if the wrongdoer confesses in words, ‘with his lips, and give voice to those matters he has resolved in his heart’. The United Nations took up Maimonides’s idea that transformative repentance is multi-dimensional and includes apology. The UN’s principles on reparation for human-rights violations insist that amends for gross wrongs, such as human-rights violations by nations, include material forms of compensation, guarantees against non-repetition, and an apology.

For many critics, this move to transpose models of apology from individuals to collectives represents what philosophers call a category mistake, that is, the attribution of a property to an entity that’s logically incapable of bearing such properties. Nations, after all, are not people. Regret and sorrow imply internality, emotional depth and capacities to feel and reflect that, critics argue, are only mistakenly attributed to nations. In addition, some more politically minded critics object that it is unjust to blame the people who make up the contemporary nation for the wrongdoings of those who made up the nation when the wrongs were committed.

These arguments overlook both the nature of large-scale wrongdoing and the nature of national identity. When societies collude in acts of racist, homophobic or religious violence, there is almost inevitably a social infrastructure of implicit approval enabling the individual perpetrators. The hands of the few might be directly undertaking the wrongful doing, but the wrongful being that permits and authorises their acts infuses the society. Mundane small acts of negligence and convenient vindication create the conditions in which violence against devalued peoples are subtly authorised and become permissible.

As to the objection that we cannot blame the people of today for the crimes of their forebears, such arguments betray a misunderstanding of what it is to belong to a nation or have a national identity. Along with the privileges we inherit by virtue of our national membership inevitably come civic obligations. Claiming national pride yet refusing national shame is not only inconsistent, it’s also unethical.

Drawing a distinction between the different dimensions of wrongs, that is, between doing wrong and authorising wrong, can help to clarify the types of reparative action that are justified. While it is incorrect and unjust to attribute guilt to individuals for acts that they did not personally commit (directly or indirectly), it is just to hold them responsible for their part in creating the conditions in which the guilty could commit those actions. Understanding different degrees of responsibility also allows those seeking justice to determine the different types of reparative action that are appropriate. Punishment might then be fitting for wrongdoers. For those whose contribution lies in ‘moral failings’, in endorsing values that condoned wrongdoing, what is required is action that will both alter their values and show that their values have been altered. This is what apology does.

Nations have not done particularly well at acknowledging the complexities of their identity. Modernist myths about the triumph of progress leave most people loathe to consider the darker sides of their own nation and its achievements. Imperialism and colonisation generated previously unthinkable wealth, and underwrote the establishment of ‘great nations’. At the same time, they devastated indigenous peoples and eradicated indigenous knowledges. The Green Revolution made possible unprecedented levels of food production and radically reduced poverty, but it also did great harm to biodiversity and unravelled myriad complex weavings of culture and agriculture. Determined amnesia and habits of erasure have long encouraged people to avert their eyes from such ‘collateral damage’, but doing so is becoming increasingly costly.

At this moment of late modernity we are witnessing, perhaps more than ever, the violence of our ‘forward-looking’ addiction in all its stark nakedness. As W H Auden wrote in The Age of Anxiety (1947):

We would rather die in our dread

Than climb the cross of the moment

And let our illusions die.

Society is so enamoured with the greatness of the future that many people are prepared to sacrifice our fellow humans and the more-than-human world, so long as someone promises to deliver us there once again. Closed-fisted attitudes to immigrants and asylum seekers, and unwillingness to alter lifestyles, even where they cause the mass extinction of other species, are cases in point.

It’s worth pausing and examining this possibility of a future that will be great again. Among other things, the promise betrays a social romanticism, filled with dreams of an idealised past. But the past was never idyllic, certainly not for many. And so long as we grit our teeth, desperate and determined to be carried by the wind of progress, the future will, most likely, continue to be infused with the past’s inequalities, failures of recognition, injustices and resentments. As Hannah Arendt wrote in 1958, we will, like the sorcerer’s apprentice, lack ‘the magic formula to break the spell’. Though perhaps if we are able to muster the strength to be vulnerable enough apologise to those human and non-human others whose lives we have damaged, ostensibly in the course of promoting our own, our capacity to act anew, and to flourish together, might be replenished.