A deterrent? Photo by Ben/Flickr

The American jurist Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr wrote in 1925: ‘If I were having a philosophical talk with a man I was going to have hanged (or electrocuted) I should say, I don’t doubt that your act was inevitable for you, but to make it more avoidable by others we propose to sacrifice you to the common good. You may regard yourself as a soldier dying for your country if you like.’

He was right that lawbreakers are not truly responsible for their actions. We make choices with a brain we didn’t choose, one constructed by a process beyond our control. However, executing or harming people to dissuade others from emulating their behaviour is a crude application of utilitarian logic. The same logic could be used to justify killing one healthy person and harvesting his organs to save five sick people. It might maximise ‘wellbeing’ but it’s an abuse of human rights. The benefit to society must be balanced against the fundamental right of the individual not to be harmed.

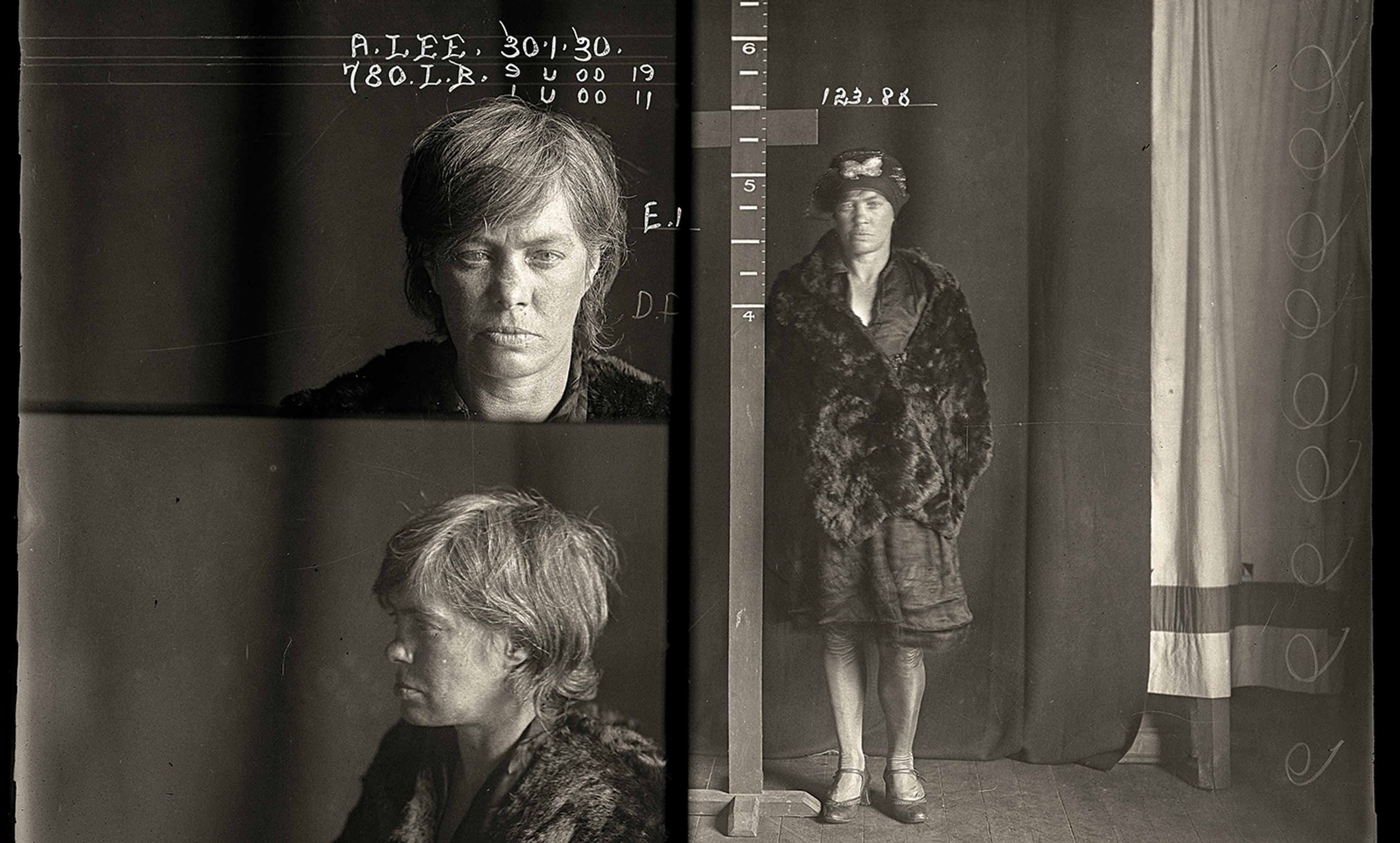

The effectiveness of punishment as a deterrent is often misunderstood. Those who fill our prisons are clearly undeterred by society’s punishments. The fact that rates of recidivism in the UK and US hover between 60 and 65 per cent only underscores the point that incarceration routinely fails to deter repeat offending. It might seem that more severe punishments would be more effective deterrents, but often the opposite is true. In a number of cases, the death penalty appears to have produced an anti-deterrent effect, increasing rather than reducing crime rates. And it’s telling that Europe’s lowest reoffending rate is in Norway’s humane prison island of Bastoy. Contrary to popular intuitions, what matters most in deterring criminal behaviour is not so much the severity of punishment but the likelihood of getting caught.

None of this means that we should let violent criminals or corrupt bankers walk free. We have the right to defend society from those who pose a threat, and create incentives for socially beneficial behaviour. But if society were to reject notions of blame and responsibility, we’d see a profound shift in how we think about punishment. The sole aim of the criminal justice system would then be to improve the future, not exact revenge for the past.

If people aren’t ultimately responsible for their actions, then there is no justification for retribution. Broadly speaking, on finding someone guilty of a crime, we have three ways of responding: punishment to deter; rehabilitation to heal; or incarceration to protect. These responses are not mutually exclusive and often overlap. For each, there are two questions to answer: will it be effective and can it be ethically justified? The answers depend on whom we’re talking about – each brain is unique. A ‘one size fits all’ approach is inefficient and unethical.

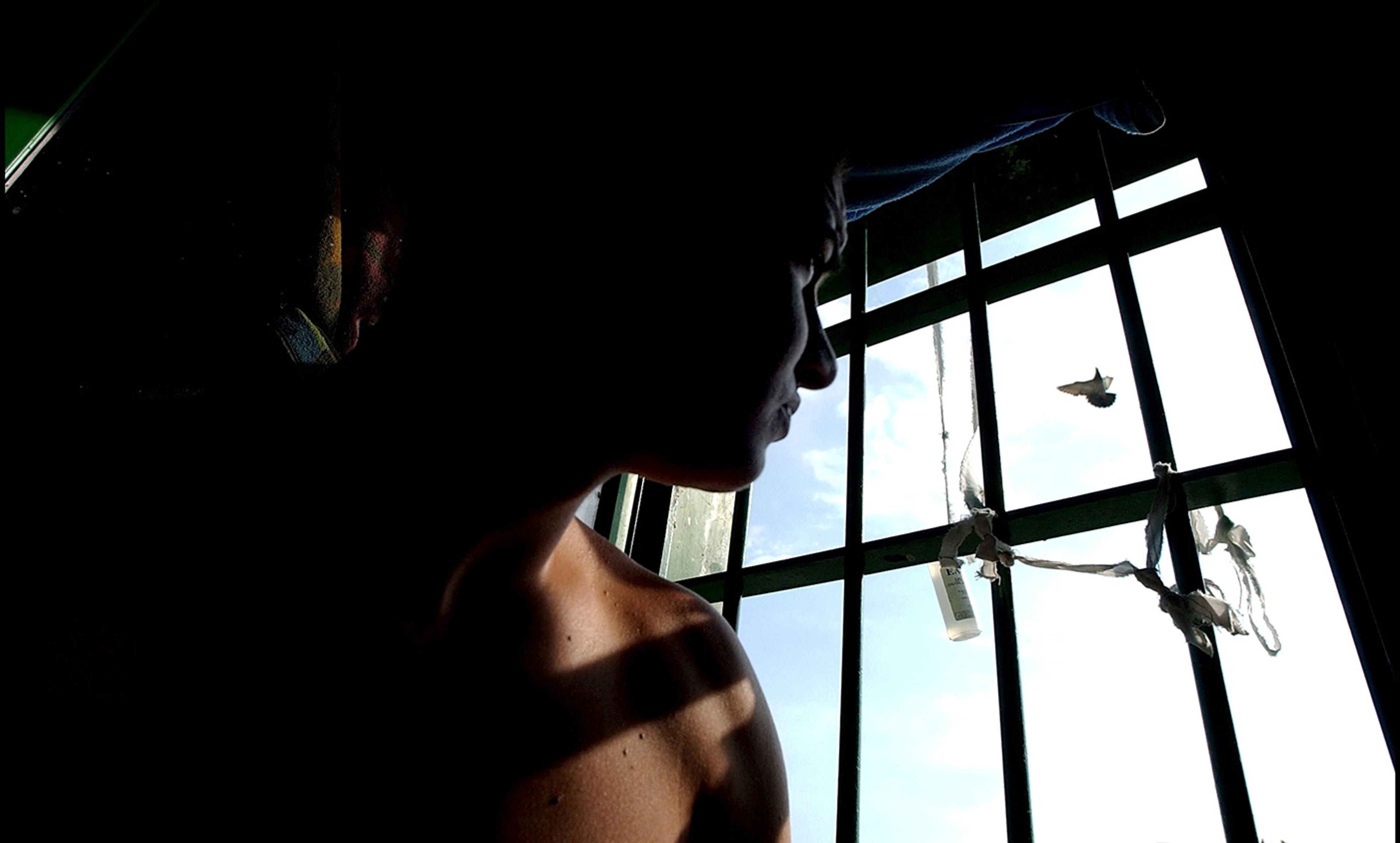

In the US, 10 times more people with serious mental illnesses are in prison than in state hospitals. In the UK, roughly 90 per cent of offenders suffer from psychiatric disorders. Harming a lawbreaker with severe mental-health problems is itself a form of injustice. Punishing an addict with little self-control creates more problems than it solves. Addicts and people with severe mental-health issues need therapeutic help, not brutal, threatening incarceration. As the prison psychiatrist James Gilligan put it in 2000, ‘one of the most effective ways to turn a non-violent person into a violent one is to send him to prison’.

The idea that the punishment should ‘fit the crime’ has little place in a rational criminal justice system. A pragmatic response would depend less on the crime and more on the specific criminal. Does an act reflect a person’s character, or is it the product of disease, addiction, exhaustion, desperation or disability? Establishing mens rea, the extent to which a crime is the result of a ‘guilty mind’, is not the test of moral responsibility, but a crucial step towards establishing the threat posed by a person, and the most constructive response to his or her actions.

Poor impulse control is common in prisoners. The neuroscientist David Eagleman and colleagues have pioneered an approach dubbed the ‘prefrontal workout’. Since a choice is the outcome of competing drives, self-control training can help tip the balance in the desired direction, enhancing the ability to resist a temptation or suppress a violent response. The prefrontal workout presents participants with a familiar provocation and shows them, visually, the competing impulses in their brain. As different mental strategies are employed, participants learn what works and what doesn’t.

Attention to individual needs can determine the appropriate rehabilitation in a given situation. For instance, restorative justice, which brings together criminals and their victims for mediated discussion, reaps a range of benefits, especially for victims, many of whom say they felt empowered, with a greater sense of closure, after taking part. Studies into restorative justice also testify to its financial and crime-reducing value. Prison-education programmes are another option that correlates with a reduction in prison violence and reoffending rates.

When the potential for modifying behaviour is slim, as with serial killers and serial rapists, extended incarceration might well be necessary. But although a psychopath makes many morally horrendous choices, they don’t include choosing the brain of a psychopath. Elementary ethical principles therefore demand that offenders be provided with humane conditions geared to facilitating a meaningful existence.

And how do we know who is most likely to reoffend? In one study, psychiatrists and parole-board members were asked to assess the likelihood of individual sex offenders reoffending. Their predictions bore almost no correlation with the outcomes. A far more successful alternative, now used by many courts, is based on algorithms that make use of detailed personal histories: drug use, childhood trauma, capacity for remorse and other such factors. Analysis shows that certain combinations of these traits and experiences dramatically increase the likelihood of reoffending. As the quality and range of criminological data improves, our predictive powers will only increase.

To improve the future rather than exact revenge for the past, a criminal justice system would deliver shorter sentences; create safer, more humane prisons; and invest in a range of rehabilitation programmes to meet the needs of those who pass through it. To think rationally about socially harmful behaviour, we need to stop seeing it as the outcome of the mystical ‘free will’ of the individual and view it instead as the product of natural causes, as a doctor views the symptoms of a disease.

Like someone afflicted with a contagious virus, the threat a criminal poses is not ultimately of his making. Exposed to the same genetic and social conditions, each of us would exhibit similar symptoms. Focusing on punishment alone does little to prevent further outbreaks. Instead, it distracts from addressing the material and cultural conditions – from inequality to racism – that breed those symptoms. Perpetuating these conditions is always the greater crime.