The Declaration of Independence by John Trumbull, 1819. Courtesy Wikimedia

In 1776, American Patriots faced problems of crushing sovereign debt, vituperative debates about immigration, and questions about the role of foreign trade. They responded by founding a government committed to open borders and free trade. The Declaration of Independence, the country’s charter document, outlined the new republic’s fundamental economic principles, ones that Americans would be wise to remember, because they are now under threat.

Americans have long held their country’s founding document sacred. John Quincy Adams, America’s sixth president, asserted on 4 July 1821 that ‘never, never for a moment have the great principles, consecrated by the Declaration of this day, been renounced or abandoned’. In 1861, Abraham Lincoln announced that: ‘I have never had a feeling politically that did not spring from the sentiments embodied in the Declaration of Independence.’ Even this year’s Republican Platform committee agrees that the Declaration ‘sets forth the fundamental precepts of American Government’. The Declaration committed that government to reversing the oppressive policies advanced by the British monarch George III and his government. In particular, they called for the free movement of peoples and goods.

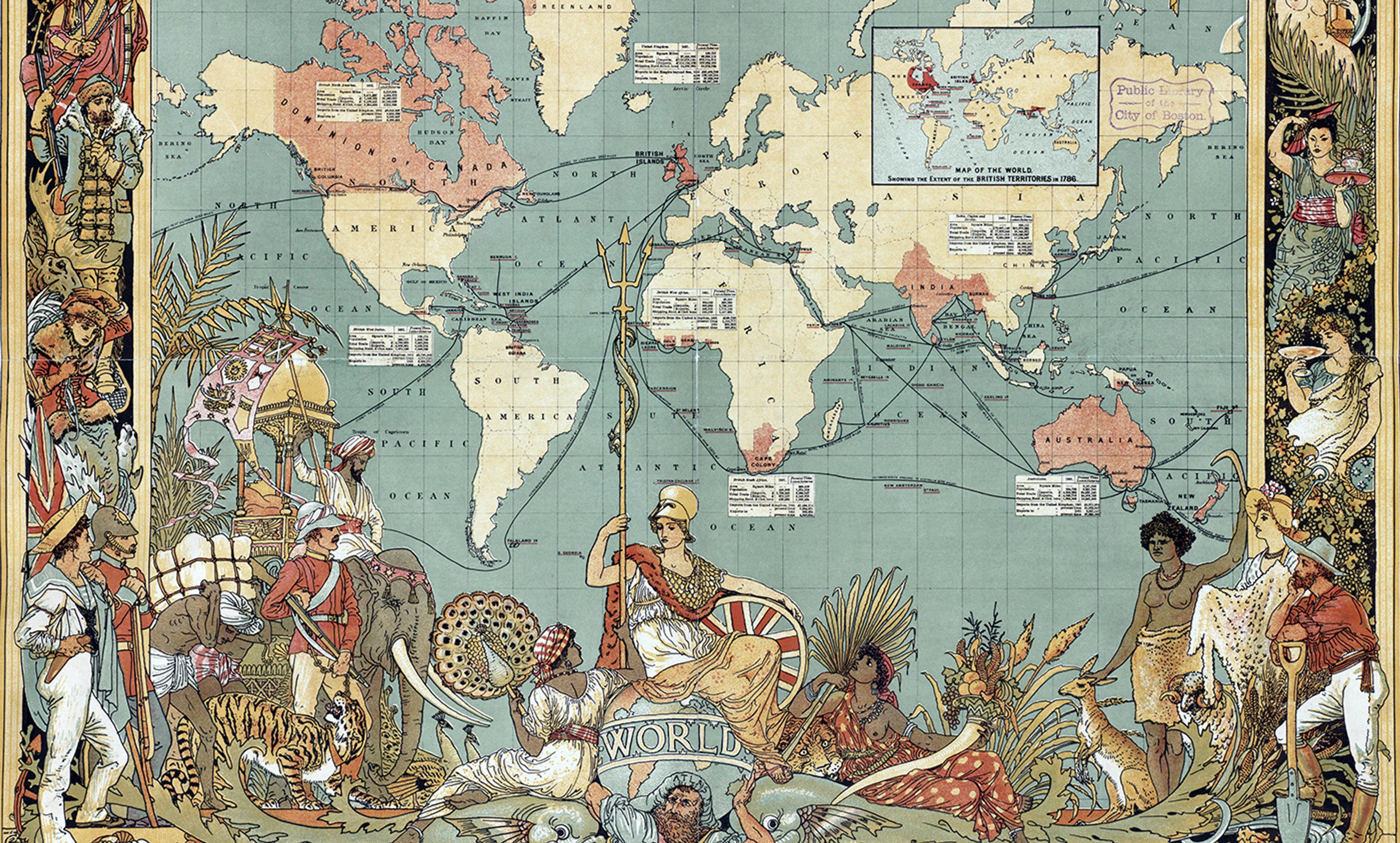

In Britain, the ministers who came to power in the 1760s and ’70s overwhelmingly believed, as do many European and North American politicians, that the only option in the face of sovereign debt is to pursue austerity measures. Like many politicians today, they were also happy to shift the tax burden onto those who had the least political capacity to object. In the 18th century, this meant taxing the under-represented manufacturing districts of England and, above all, taxing the unrepresented North Americans. Today, this often means regressive taxation: taking less from those with more.

Patriots on both sides of the Atlantic who opposed the British governments of the 1760s and ’70s did not deny that heavy national debts could be oppressive, but they insisted that the dynamic interplay of producers and consumers was the key to generating economic growth. Unlike their ministerial opponents, they believed that the best way to pay down that debt was for the government to stimulate the economy. They pointed out that the colonies represented the most dynamic sector of Britain’s imperial economy. The more the colonies grew in population and wealth, the more British manufactured goods they would consume. Since these goods were indirectly taxed, the more the Americans bought, the more they helped to lower the government’s debt. Consumption in the colonies was thus ‘the source of immense revenues to the parent state’, as the founding father Alexander Hamilton put it in 1774.

When Americans declared independence in 1776, they set forth to pursue new, independent economic policies of free trade and free immigration. The Committee of Five, including John Adams, Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin, who drew up the Declaration of Independence, condemned George III for ‘cutting off our Trade with all parts of the world’. The British government had long erected tariff and non-tariff barriers to American trade with the French and Spanish colonies in the Caribbean and South America. By doing so, they deprived Americans both of a vital outlet for their products and of access to hard currency. This was why Franklin had, in 1775, called for Britain to ‘give us the same Privileges of Trade as Scotland received at the Union [of 1707], and allow us a free Commerce with all the rest of the World’. This was why Jefferson called on the British imperial government not ‘to exclude us from going to other markets’. Freedom of commerce, admittedly one that was accompanied by state support for the development of new industries, is foundational to the United States.

The founders’ commitment to free trade stands in stark contrast with Donald Trump’s recent declaration for American ‘economic independence’. Trump insists that his economic programme echoes the wishes of the founding fathers, who ‘understood trade’. In fact, Trump’s economic principles are the reverse of those advocated by the authors of the Declaration. Like the British government of the 1760s, against which the Patriots defined themselves, Trump focuses narrowly on America’s role as a ‘dominant producer’. He is right to say that the founders encouraged manufacturing. But they did so by simultaneously supporting government subsidies for new American manufactures and advocating free trade agreements, such as the Model Treaty adopted by Congress in 1776 that sought to establish bilateral free trade. This was a far cry from Trump’s call for new ‘tariffs’.

The Declaration also condemned George III for his restrictions on immigration. Well-designed states, patriots believed, should promote immigration. This was why they denounced George III for endeavouring to ‘prevent the population of these states’. George III, the American Patriots pointed out, had reversed generations of imperial policy by ‘refusing to pass’ laws ‘to encourage … migrations hither’. Patriots, by contrast, welcomed new immigrants. They knew that British support for the immigration of Germans, Italians, Scottish Highlanders, Jews and the Irish had done a great deal to stimulate the development of British America in the 18th century. State-subsidised immigrants populated the new colony of Georgia in the 1730s. Immigrants brought with them new skills to enhance production, and they immediately proved to be good consumers. ‘The new settlers to America,’ Franklin maintained, created ‘a growing demand for our merchandise, to the greater employment of our manufacturers’.

Nothing could be further from the animating spirit of America’s charter document than closing the country’s borders. Restrictions on immigration more closely resemble British imperial policies that spurred American revolt and independence.

The Declaration of Independence was much more than a proclamation of separation from the Mother Country. It provided the blueprint, the ‘fundamental precepts’, for a new government. Americans broke away from the British Empire in the 1770s, in part, because they rejected restrictions on trade and immigration.