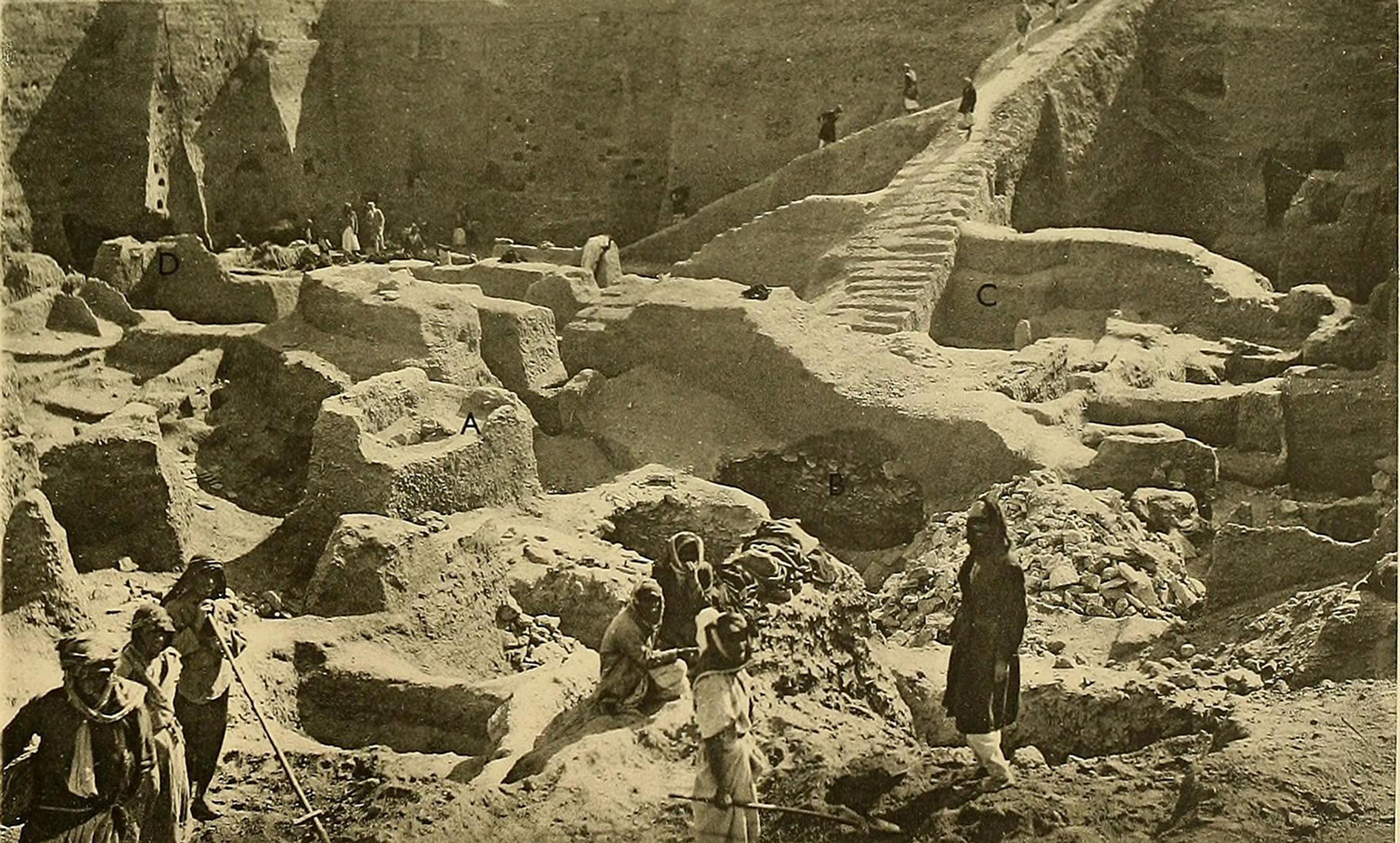

Photo courtesy the author

We had walked for five days through the mountainous rainforest of the Mosquitia region of eastern Honduras. My companions were five Pech men with whom I often worked. The Pech are an indigenous group, and they almost certainly are descended from the people who built and inhabited the impressive archaeological sites we were visiting. It wasn’t raining just then, and we had a good fire going. We had harpooned some cuyamel fish in the river and were frying them along with green bananas, a Honduran staple. I never fantasised about food in the rainforest, only about dry clothes.

As we were eating, Don Cipriano, the oldest of the Pech and an expert on the region’s archaeological sites and forests, asked if I had heard the lost city legend – the one about La Ciudad Blanca, or the White City. ‘I have heard the stories,’ I said. Everyone in the region has heard them.

‘It’s nearby,’ he told me. ‘Just up this river, up on top of a hill.’ I asked him if we should go see it. He told me we couldn’t. The site was sacred, he explained, and was the refuge of indigenous gods who had fled when the Europeans had arrived nearly 500 years earlier. There were gods from all seven indigenous groups, and if you went there and couldn’t speak to each one, they wouldn’t allow you to leave, he added. Nobody knew all seven languages – not even him.

My time as an archaeologist in Honduras began some 25 years ago, and from the start I knew that I could accomplish nothing without the Pech people. Over weeks-long expeditions, Pech guides taught me how to start fires in the rain, fish, find my way in the rainforest, gather food, and make a raft and a shelter. I got pretty good at these activities but nothing like the Pech. There wasn’t anything they didn’t know about their own territory.

The archaeological and linguistic data suggest that the Pech have at least 1,000 years of history in the region. They’ve lost much of their traditional lands to encroaching farmers and cattle, but they have not lost their history – or their knowledge of the ruins that lie underneath the thick vegetation of the forest.

All told, Pech guides have taken me to see about 150 archaeological sites, and I have documented them, drawing maps, writing up notes, and taking photos. I have interpreted and contextualised these sites – but I have ‘discovered’ nothing.

My viewpoint contrasts sharply with that of others who have explored the region looking to make a ‘discovery’. Over the past century, there have been numerous expeditions to find a mythical lost city in the Mosquitia rainforest. La Ciudad Blanca keeps being discovered, over and over again; practically any time anyone finds the remains of any settlement, they call it that. I know of half a dozen large sites that have each been deemed ‘the White City’; there must be others. In all cases, the ‘discoverers’ are outsiders, and their find is presented as a heroic accomplishment. They want us to believe that they are intrepid explorers – achieving what others couldn’t because of their guts, money, technology, business acumen and grit.

Nothing in their description is accurate. The cities aren’t lost; the people living in these areas know all about them. And the original legends do not even reference cities; rather, they refer to locations that, for whatever reason, represent a golden age for indigenous communities. Even the landscape is not particularly dangerous; children grow up there, after all.

Archaeologists often say: ‘It’s not what you find, it’s what you find out.’ We are not in pursuit of objects but rather an understanding of the past. My work has never been about finding sites. It’s about finding out how leaders gained and maintained power, how these ancient societies interacted with other groups, and how such societies situated themselves across the landscape.

Most archaeologists spend a significant amount of time with local residents. They know that to understand a place, you have to walk through it and you have to live in it. But over the years, technologies and methods have emerged that help to speed up archaeological investigations. First there was aerial photography, then satellite imagery, and most recently LIDAR (light detection and ranging), which uses millions of laser light pulses fired from a low-flying plane to get data about the landscape. So much data is captured, in fact, that you can remove some of it, like a representation of the forest canopy, and have more than enough to create a detailed 3D map of the surface beneath, allowing you to pick and choose what you want to keep.

These are great technologies, but while they offer efficiency, they also have the potential to decrease critical interactions between an archaeologist and the community. By ‘finding’ a lost city from the air, archaeologists fail to understand the depth and breadth of knowledge and experience that communities have of their place and their past. The illusory ‘finding’ seems important. The ‘finding out’, the delayed gratification, is replaced by the immediacy of the ‘discovery’.

In addition to efficiency, such technologies also elevate the visual – and they provide a seemingly unobstructed view that comes from gazing upon the world from a rarefied position. The observer, with this powerful view, assumes a de facto position of power and dominance over whatever is distantly viewed – that viewer’s interpretation is not challenged by other viewpoints. This focus on the visual, and the decontextualisation that it allows, is fundamental to archaeological approaches that value a certain type of so-called discovery. In archaeology, this is considered the ‘hegemonic gaze’, wherein the explorer above is in a position of power, and the landscape below is the object of desire to be documented.

Knowing this might not be enough to avoid these issues when I use such technologies. But some explorers have allowed such power imbalances to permeate their work. In 2012, for example, a group led by a filmmaker and a writer undertook a LIDAR-based trip and claimed to have found the lost White City of Honduras. After some initial backlash, the ‘lost city’ was comically renamed the City of the Jaguar, which has no basis in local history, and was referred to as the City of the Monkey God, which also has no grounding. Local indigenous peoples maintain that they always knew about this place and had intentionally left it alone. Its ‘discovery’ and naming by outsiders was offensive to them on many levels.

The American feminist and legal scholar Catharine MacKinnon in Feminism Unmodified (1987) challenged scholars to ask themselves how they know things: ‘Not exactly why should I believe you, but your account of why your account of reality is a true account.’ By claiming a non-situated position, as if it were possible to operate free of perspective and bias, archaeologists inherently support and reinforce the status quo; this way of asserting power too often goes unnoticed.

Out of this type of questioning, some archaeologists have come up with an alternative mode of investigation known as ‘sensory archaeology’. Sensory archaeologies challenge the power-dominated fantasy of exploration seen in the 2012 ‘lost city’ project, helping to expose how a visual (or hypervisual) position creates and reflects a problematic relationship between the investigator and the subject of the investigation. Though my research is not explicitly sensory archaeology, my attempts to immerse myself in a place and within local communities, and to contextualise discoveries, follow similar guiding principles.

Sitting by the campfire with Don Cipriano and the other Pech men after days of exhausting trekking, I couldn’t help but recognise my limits. Nothing felt as straightforward as it looked on the map. La Ciudad Blanca that Cipriano pointed to at the top of the hill might have been nothing physical at all – none of us had seen it, after all – or it might have been a place that others had documented before. It wasn’t that important. What mattered, as I sat there, was living among these people, sharing the adventure of exploring the past, and understanding their ways of looking at the world. I still had so many languages to learn.