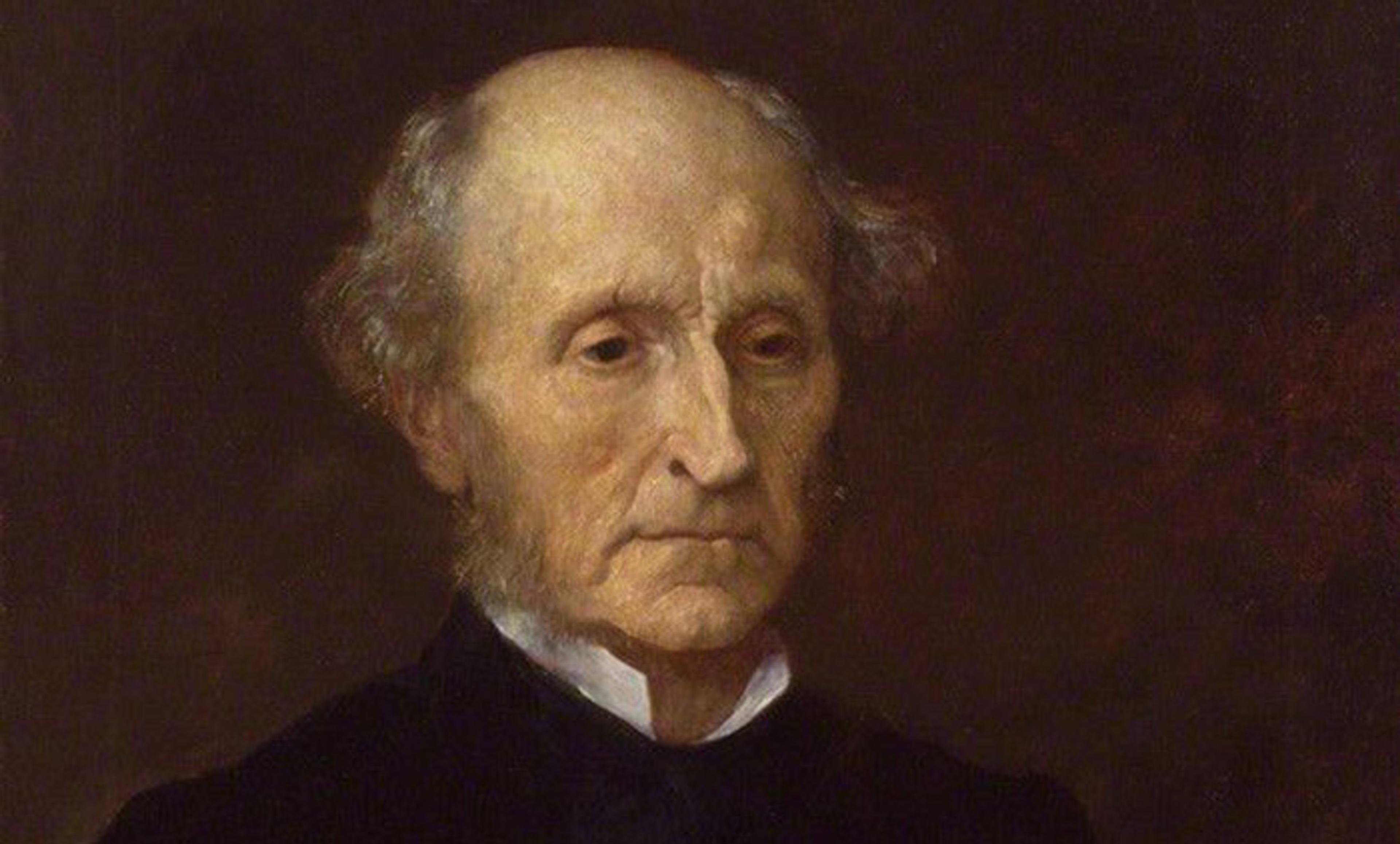

Telling-tales; a comet above Augsburg in 1618. Courtesy Wikipedia

After Hurricane Katrina in 2005, the American pastor John Hagee became notorious for blaming the devastating storm on the ‘sins’ of the people of New Orleans. The outcry forced him to recant his statement. More recently, in the wake of Hurricane Harvey, a sociology lecturer lost his job for the comparatively milquetoast suggestion that a vague karmic influence might have lured the storm to the conservative stronghold of Texas.

The surprising thing, from a historical point of view, is not that they believed that natural disasters are related to human actions, but rather the outrage this suggestion caused. Today, we seem to rebel at the idea that nature takes sides, or that the victims of disaster somehow get their just desserts for sin. We’d rather put the chaos of a natural disaster down to the vicissitudes of geography, meteorology and luck than any broader plan. But this wasn’t always the case.

Compare a news report from 1792, describing the demise of a group of Philadelphia pleasure-boaters who were killed by a storm on Sunday, 4 July. The article goes into gleeful and gory detail, and says the daytrippers brought it upon themselves for daring to make light of the Sabbath. Across the Atlantic world, every storm or comet or two-headed baby sparked the publication of pamphlets urging the authorities to take action to avert God’s judgment.

These accidents of nature were known as ‘prodigies’. A non-exhaustive list might include floods; rains of blood or body parts; miscarriages, human and animal; volcanic eruptions and earthquakes; comets, eclipses, and conjunctions of the planets; apparitions of armies in the sky; and beached whales. What united this Borgesian collection was its strangeness. Each of these phenomena departed from the ‘norm’, but not enough to be considered a true miracle. They occupied a middle ground between natural and supernatural: the preternatural.

In theory, prodigies could be explained by natural causes. But in creating them, nature wasn’t tending to business as usual. This strange, quirky, slippery realm, the realm of the monstrous, fulfilled a human need to see the moral order reflected in the non-human domain. Prodigies allowed humans to see their own desires, fears and political judgments woven into the fabric of nature itself. In a secularised form, this impulse is still with us today.

‘Monster’ comes from the Latin word monstrum meaning ‘divine omen’ – and prodigies, above all, were signs. In medieval Europe until the 18th century, people believed that God manifested his pleasure or displeasure through signals that ranged from the intimate to the cosmic. In the 17th century, the Puritan minister Anne Hutchinson gave birth to a ‘monstrous’ ball of tissue that resembled a bunch of grapes; her religious opponents in New England claimed that the corruption of her foetus proved the corruption of her theology and her morals. As a pamphleteer put it: ‘See how the wisdom of God fitted this judgment to her sin in every way, for look as she had vented mis-shapen opinions, so she must bring forth deformed Monsters.’

A comet, on the other hand, was always political. ‘Corruption’ of the otherwise-unchanging stars could be seen from all over the Earth, so astronomical anomalies meant something momentous was afoot, like the death of a king or the downfall of an empire.

In 1677, a woman who practised ‘the wicked art of fortune-telling’ prophesied about a comet that had appeared in the English sky. ‘She said that the late blazing star … signified that the best (or greatest) person of this kingdom’ – the king – ‘should before next Michaelmas be poisoned.’ Her prophecy survives only because a spy reported it to Crown officials – not as a joke, but as a serious threat to the state. Her listeners would have remembered with horror the great fire and plague of London just a decade before. Not one but two ‘monstrous’ comets had preceded that double catastrophe; opponents of the king used the new comet to show that the monarchy had lost God’s favour.

For much of history, then, prodigies wielded immense public power. They measured how humanity was faring in God’s plan, and people at the highest levels of society took them very seriously. After the great comet of 1680, one pamphlet attacked Roger L’Estrange – the king’s much-despised official censor who tried to keep a lid on preternatural speculation – and dared him to speak now that the heavens themselves had declared war against him:

Now crack-fart Roger, let your crack-farts fly!

The tell-tale comet, scribble out th’ sky!

Yet, beyond bawdy name-calling, some pamphleteers stirred up real danger. One of the Puritan patriarchs of early America, Increase Mather, grew so concerned about the misinterpretation of prodigies that in 1684 he wrote up a series of rules. Mather advocated for a kind of Bureau of Preternatural Investigation, making himself the first agent and publishing a list of carefully vetted ‘true’ prodigies, verified by numerous independent witnesses. He tracked down stories of cows struck with strange diseases, of suspected fornicators hit by lightning, and of villages burned by natives. The idea was to sort out how sin affected the geography, the politics, and even the climate of New England. For Mather, and for many in the pre- and early modern world, there was no such thing as a truly natural disaster – because nature, since Eden, had been corrupted by human sin.

The Enlightenment of the 18th century went on to naturalise disasters. New views of science and God made it fashionable to emphasise that everything in the world was a prodigy, because God had created it. All strange and wondrous things became objects of scientific enquiry, separated from moral meaning. At the same time, rulers became more effective at shutting down seditious pamphleteering that urged monarchs and other sinners to repent.

For the periwigged Enlightenment philosophes, nature became a beautiful, orderly, law-governed place. Later, the Romantics emphasised nature’s power and otherness. But both groups took it for granted that nature acted without regard for petty human concerns. When an earthquake in Lisbon killed thousands of people in 1755, few watchers blamed it on human foibles; in fact, it precipitated a crisis of faith, as philosophers wondered how a benevolent deity could inflict such suffering.

Yet removing a wrathful God from our explanations for strange events hasn’t excised the desire for blame. When weird things happen, we still crave the sense of control we get from believing that there’s a reason, that they lay bare the good and evil in society. The human toll of natural disasters tells a story of collective apathy that allows a famine to unfold; corporate greed and unchecked development causes a flood. When nature throws something unexpected our way – as it did to us here in Houston, when I was writing this article from the island that used to be my neighbourhood – we are all apt to look, despite ourselves, for meaning in the madness.