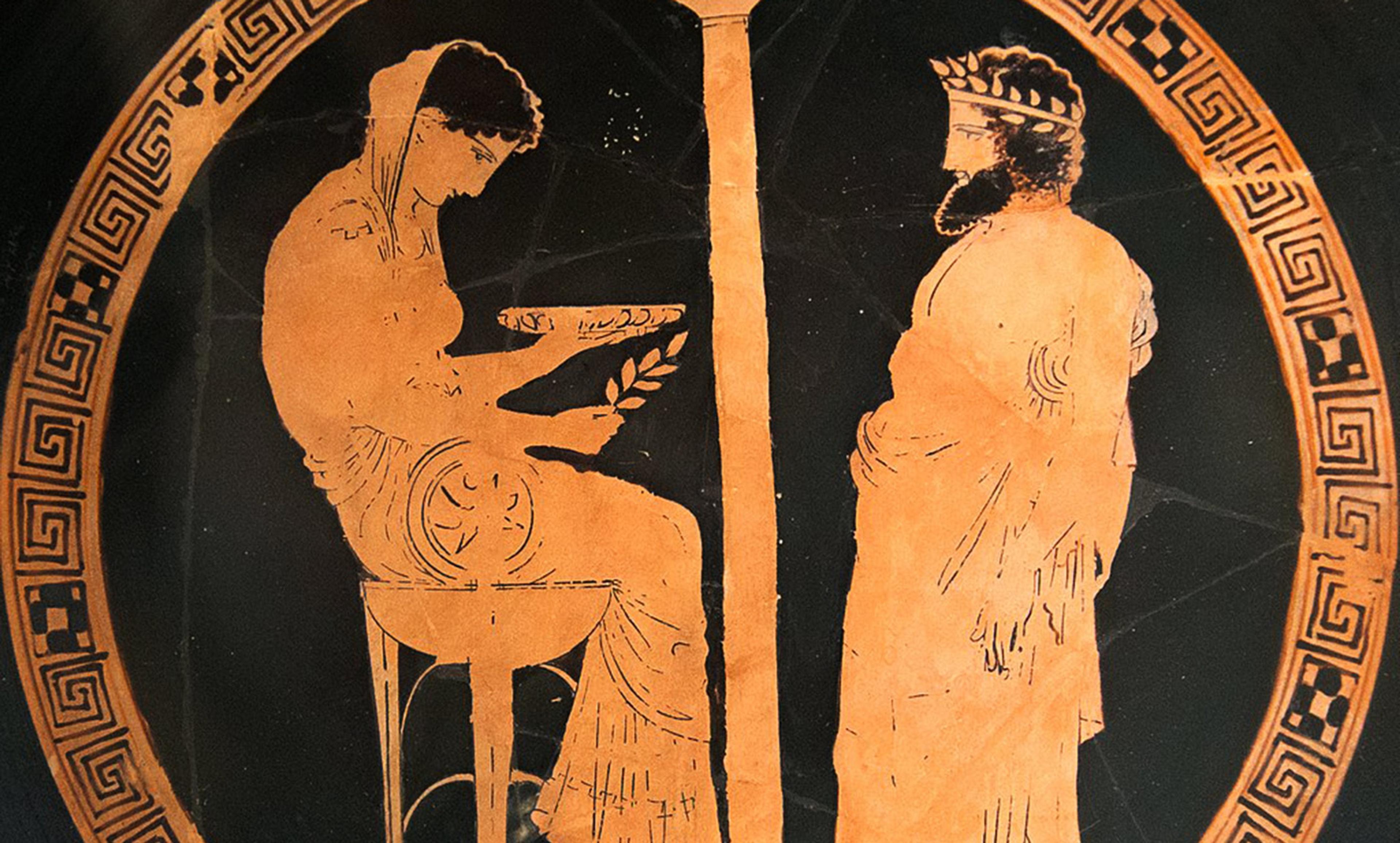

An Attic red-figure kylix from Vulci (Italy), 440-430 BC, depicting King Aigeus in front of the Pythia at the Oracle of Delphi. Courtesy Wikimedia.

In 480 BCE, the citizens of Athens were in more trouble than it is possible for our modern minds to fathom. Xerxes, the seemingly omnipotent son of Darius the Great, had some unfinished business left to him by his father. A decade earlier, at the Battle of Marathon in August 490 BCE, the miraculous had happened: the underrated Athenian army had seen off Darius and his mighty Persian horde, saving the threatened city-state from certain destruction. Now Xerxes had invaded Greece again, to finish the work his father had started, and he’d assembled a vast army that the Greek historian Herodotus (typically exaggerating) put at 5 million, but – though modern scholars disagree on precise numbers – was likely to have been a still-overwhelming force of 360,000, on top of a gigantic armada of 750 ships. Confronted with an insurmountable foe and almost certain destruction, the hard-pressed Athenian leadership requested the services of the world’s first political risk consultant.

Already, by 480 BCE, the Pythia of Delphi was an ancient institution. Now commonly known as the Oracle of Delphi – when, in ancient Greek, the oracles were the pronouncements that the Pythia dispensed – the Pythia were the senior priestesses of the Temple of Apollo, the Greek God of Prophecy. For more than 1,100 years (until 390 CE, when radical Christians chased the last Pythia out of Parnassus), they were viewed as the most authoritative soothsayers in Greece. Pilgrims descended from all over the ancient world to the temple on the slope of Mount Parnassus to have their questions about the future answered. From the small, enclosed chamber at the base of the shrine, the Pythia (there were three priestesses on call at any time) delivered her oracles in a frenzied state – the likely result of imbibing the hallucinogenic vapours rising from the clefts in the rock of Mount Parnassus, which we now know sits atop the intersection of two tectonic plates.

The Pythia would be sitting in a perforated cauldron astride a tripod. Pilgrims reported (and Plutarch, who for a time served as high priest at Delphi, assisting the Pythia in her mission, confirmed) that as she inhaled the strange vapours her hair would stand on end, her complexion altered, and she would often begin panting, her voice assuming an otherworldly tone. In classical days it was said that the Pythia spoke in rhyme, in pentameter or hexameter. To put it in modern terms, the Pythia was clearly as high as a kite. But let’s look at the Pythia afresh, for I would argue that the Temple at Delphi was effectively the world’s first political risk-consulting firm.

Since the height of the Persian Wars, political and business leaders have looked to outsiders blessed with seemingly magical knowledge to divine both the present and the future. While the tools of divination have obviously changed, the pressing need for establishing the rules of the road for managing risk in geopolitics have not. The question for political risk analysis remains the same as it was during the heyday of the Pythia: with superior knowledge (spiritual or intellectual), can we reliably do this?

The Pythia’s prognosticating advantages, not least her outsider status, curiously track the qualities that political risk firms look for in their best analysts today. In their isolation at Mount Parnassus, the Pythia were not in danger of elite capture, and the curse of analytical groupthink that so often follows, in terms of what they predicated. This is the curse that doomed so many modern-day analysts to be so very wrong about the Brexit vote because they didn’t bother to look outside the hermetically sealed elite shell of London; or the startling advent of Donald Trump (they never left the East Coast corridor). Physical, intellectual and emotional distance have great analytical value.

Yet despite being isolated, the Pythia had limited but regular contact with the elites of the day who made the arduous trek to visit them. Over time, the priestesses at the Temple of Apollo came to understand what it was their clients wished to know, and how to provide exactly what they lacked; independent, outside, authoritative advice. It should be noted that the Pythia were chosen from a group of highly educated women, well-acquainted with the world. It is this strange and unique mix of special knowledge, education, distance from (and yet connection to) the centres of corruption and power, that describes the ideal CV for political risk analysts today.

The Pythia offered practical counsel that could shape future actions, just as political risk analysts do today – though we’d use modern jargon and call it ‘policy’ in the public sphere, and ‘corporate strategy’ in the business world. It is amazing how good a political risk record the priestesses actually had. Between 535 and 615 of the oracles have survived to the present day, and well over half of these are said to be historically correct. (I can name a goodly number of modern firms that would kill for that record.)

There has always been a market to answer basic political risk questions: can the Persians be stopped, and if so how? Will the UK vote for Brexit? Will Trump become president? Then as now, those with a reputation for getting basic political risk questions right were venerated, just as those who failed were over time discredited. Crucially, on the biggest political risk question Delphi was ever presented with – Xerxes’ invasion – the Pythia came through with flying colours. In her peculiar poetic and riddling fashion she suggested a ploy to get the Athenians off the hook. She recounted that when Athena, Greek goddess of wisdom and the patron of her namesake city, implored her father Zeus to save Athens, he told her that he would grant them ‘a wall of wood that alone should be uncaptured, a boon to you and your children’.

Naturally, the Pythia’s mysterious oracular pronouncements required interpretation by the city leaders of Athens. One of them, Themistocles, argued that a wall of wood specifically referred to the Athenian navy, and persuaded the city’s leaders to adopt a maritime-first strategy against the Persians. This policy – concocted by the Pythia – led directly to the decisive naval Battle of Salamis, the turning point that brought to an end the Persian risk to Athens’s very survival. To put it mildly, the Pythia had proven to be well worth her political-risk fee – both the direct monetary payment customarily made to her by pilgrims, and the larger donations to the gods, which secured petitioners an advanced place in the line.

To Dare More Boldly: The Audacious Story of Political Risk by John C Hulsman is out now via Princeton University Press.