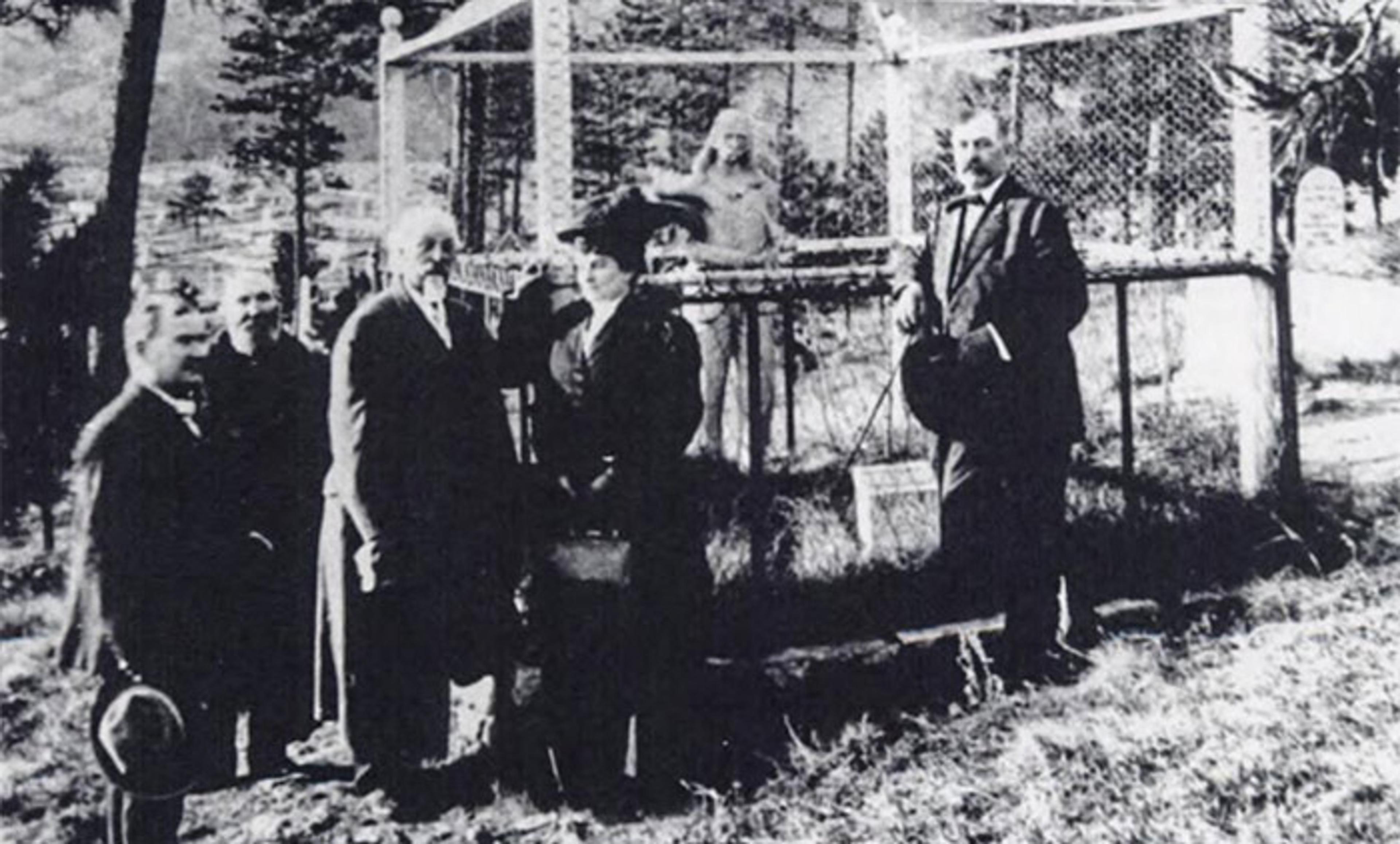

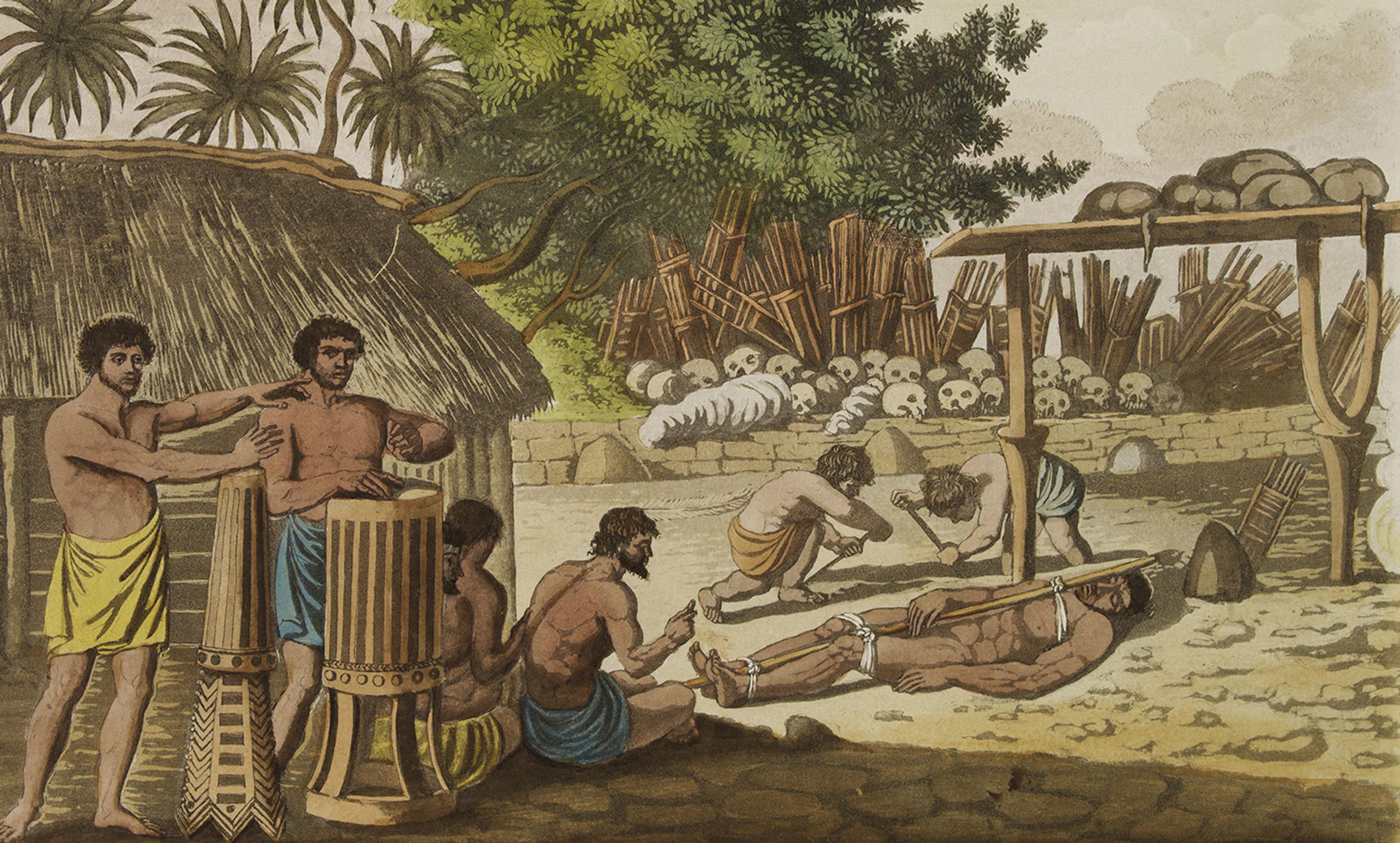

Aquatint depicting the Morai (Tahiti), practice of human sacrifice. From Giulio Ferrario’s work Le Costume Ancien et Moderne . Courtesy Wikimedia

To mourn the death of aristocrats, the Ngaju people of Borneo performed a sacred ritual that began at sunset with the tying of a slave to a pole, involved dancing throughout the night and stabbing the victim, and then climaxed with the slave collapsing in a pool of his own blood at sunrise. In other parts of the world, methods of human sacrifice included bludgeoning, drowning, strangling, burning, decapitation, burial and even being used as the rollers to launch a newly built canoe. How could something as costly as human sacrifice have been so common in early societies? And why did these rituals need to be so dramatic and gory?

Anthropologists and historians have put forward the ‘social control hypothesis’ of human sacrifice. According to this theory, sacrificial rites served as a function for social elites. Human sacrifice is proposed to have been used by social elites to display their divinely sanctioned power, justify their status, and terrorise underclasses into obedience and subordination. Ultimately, human sacrifice could be used as a tool to help build and maintain systems of social inequality.

Hereditary social inequality was the first form of social complexity to have emerged in human history, and gave rise to chiefdoms, kingdoms and political states. By helping to build and maintain social inequality, human sacrifices could have helped us establish the kinds of modern societies that we live in today. One line of support for this theory is found in the archaeological record of Southwest North America where the remains of ritually slaughtered individuals have been found in the same regions as the remains of early hierarchical societies. However, up until now, this idea had not been rigorously tested.

With my colleagues at the University of Auckland and elsewhere, we recently tested the social control hypothesis using a sample of 93 Austronesian-speaking cultures, and published our findings in Nature. The Austronesian family of cultures originated in Taiwan, developed outrigger canoes, and were some of the greatest ocean voyagers in human history. Thousands of years before the Viking sagas, the Austronesians had begun their great expansion, sailing west to Madagascar, east to Easter Island and south to Aotearoa – a total area covering more than half the world’s longitude.

In early Austronesian cultures, a wide range of events called for human sacrifice, including burying an important chief, preparing for war, constructing a new canoe, appeasing the gods, or simply hoping for a season of plentiful crops. The victims tended to be of low social status and the perpetrators were the social elite. While it might have been the gods who demanded the ritualised human sacrifice, it was often the chiefs and priests who conveniently got to choose the victims.

By collecting data on Austronesian cultures from the historical records of early explorers, missionaries and anthropologists, we built the Pulotu database of Pacific religions. As part of this database, we identified whether traditional Austronesian cultures practised human sacrifice, and the extent of inherited social inequality within societies (social inequality included such things as hereditary slave casts and ruling lineages).

Human sacrifice was surprisingly common. It occurred in almost half of the cultures we studied (43 per cent). While it was relatively scarce in egalitarian societies, human sacrifice was practised in the majority of cultures with strictly inherited class systems. This suggests that there is a relationship between social inequality and human sacrifice, but it doesn’t tell us whether human sacrifice leads to social inequality or vice versa.

Using a language-based family tree and statistical methods developed by evolutionary biologists, we were able to model how human sacrifice and social inequality evolved in the prehistory of Austronesia. These phylogenetic methods enabled us to target causality by modelling the order in which human sacrifice and social inequality tended to arise, as well as the effects they had on one another. We found strong support for the social control hypothesis: human sacrifice helped to build strictly inherited class systems, and prevented cultures from becoming more egalitarian.

The overlap in religious and political authority allowed ritualised human sacrifice to be used by social elites to build and maintain social inequality. In Austronesian cultures, specialist religious knowledge, such as how to perform elaborate prayers or magic rituals, could be handed down through elite family lineages. In many cases, these families claimed to be favoured by the gods or to have descended from them. Religious superiority was used to justify social status, and often the chiefs and priests were either one and the same person, or drawn from the same lineage.

There are innumerable ways in which religious beliefs and practices favoured those in charge. For example, the Bughotu of the Solomon Islands believed that the gods demanded food sacrifices, but for the food to make its way to the gods it first had to be eaten by the high priest. We also know from ethnographic descriptions that those who were out of favour with social elites had a habit of being sacrificed. This highlights how ritualised human sacrifice could be used by social elites to remove dissidents, instil fear, and justify authority in early Austronesian societies.

Despite being scarce today, ritualised human sacrifice was performed in early human societies throughout the world. During the First Dynasty of ancient Egypt, the graves of Pharaohs were accompanied by ‘retainers’ or human sacrifices who were believed to provide assistance in the afterlife. In Europe, mutilated bodies are found buried in peat pits, some of which are up to 8,000 years old and are accompanied by religious paraphernalia such as crucibles, idols and sacred plants. Aztec high priests extracted the beating hearts of victims in front of visiting dignitaries from competing communities. Often the victims were themselves captives from one of the competing communities, and the dignitaries returned home trembling in fear.

Religion is often un-falsifiable, and can express all-too-human whims. When religious truth is placed in the hands of a powerful social elite, religion can become a tool for nothing more high-minded than building and maintaining social control. That control is most vividly and bloodily seen through the widespread use of ritualised human sacrifice.