Excavations at Banias Photo by Derek Winterburn/Flickr

In the complex world of Middle Eastern boundary disputes, spare a thought for Banias, the ancient City of Pan. Straddling a strategic crossroads, it has for centuries seen masters come and go. Today’s tug-of-war is between Syria and Israel, for Banias is located in the Golan Heights. The settlement was based on a beautiful spring at the foot of Mount Hermon on whose summit, according to an Arab proverb, it is winter, on whose shoulders it is autumn, on whose flanks spring blossoms, and at whose feet eternal summer reigns. The waters from the spring eventually lead into the Sea of Galilee, Israel’s largest reservoir.

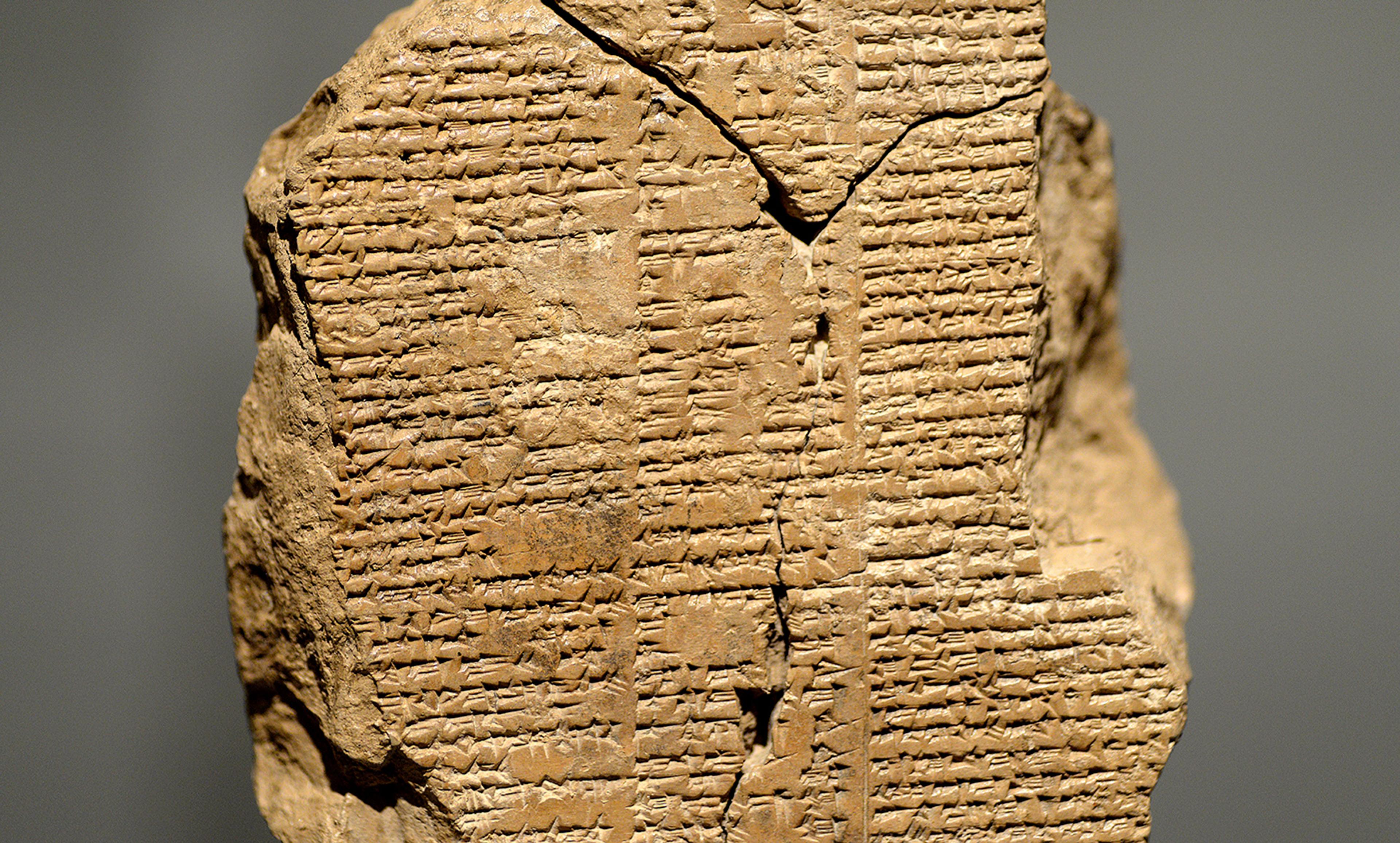

The Canaanites (Joshua XI, 16-17) first settled the place, worshipping the divinity of the spring. In 198BCE it was the scene of the Battle of Panium between the Macedonian armies of Ptolemaic Egypt and the Seleucid Greeks of Syria, whose elephants won the day. To commemorate their victory, the Greeks built a temple to Pan, the goat-footed god of nature and wild things, and creator of panic in the enemy. The local name became Paneas, the origin of modern Banias – Arabic has no ‘p’, so uses ‘b’ as the closest sound.

The Romans renamed it Caesarea Philippi (4BCE-43CE), after the son of Herod the Great, and the city was rich in biblical associations. Here it was that Jesus told Peter he would be the Rock of the Church and be given the keys of the kingdom of Heaven (Matthew XVI, 13-18).

Conflicts continued here between the pagan tradition and Christianity, then between Christians and Muslims. Under the Crusaders, the site was known as Belinas and on the hills above, an hour’s walk away, they built the imposing Subeiba Castle, today called Nimrod, which still dominates the pass leading up towards Damascus. A Christian sanctuary dedicated to St George – whom the Muslims called al-Khidr (the ‘green one’) – was built above the grotto; later, it was converted into a mosque. Today it is maintained by the local Syrian Druze people of the Golan.

After the First World War, Banias found itself contested by both the British Mandate over Palestine and the French Mandate over Syria. Britain wanted to retain control of the whole Jordan water system, while France wanted total control of the route linking Damascus and the Golan to Tyre on the Lebanese coast. The case of Banias was among the compromises reached, where Britain agreed for the line to be drawn 750 metres south of the springs so that it fell to the French. The French Mandate came to an end in 1946, and Syria gained its independence as a state within the same borders.

When the state of Israel was created in 1948 without the agreement of its Arab neighbours, the stage was once again set for conflict. Israel insisted on control of the Jordan headwaters, but Syrian troops refused to withdraw from Banias. Israel began work in 1951 on a channel to drain the nearby Huleh swamps, bulldozing Arab villages that lay in the way, so Syria reinforced its military presence. A swimming area on the stream was called the ‘Syrian Officers’ Pool’.

Throughout the 1950s and ’60s, Syrian and Israeli units attacked and counter-attacked, each determined to take control of the vital snowmelt from Mount Hermon. Israel announced a plan to divert the water from the Banias stream into its National Water Carrier, and Syria countered with a plan to build a canal from Banias to Yarmouk. When the heavy machinery moved in to start on the project, Israeli guns destroyed them.

In June 1967, the penultimate day of the Six Day War saw Israeli tanks storm into Banias in breach of a UN ceasefire accepted by Syria hours earlier. The Israeli general Moshe Dayan had decided to act unilaterally and take the Golan. The Arab villagers fled to the Syrian Druze village of Majdal Shams higher up the mountain, where they waited. After seven weeks, abandoning hope of return, they dispersed east into Syria.

Israeli bulldozers razed their homes to the ground a few months later, bringing to an end two millennia of life in Banias. Only the mosque, the church and the shrines were spared, along with the Ottoman house of the shaykh perched high atop its Roman foundations. Within days, Israeli volunteers began building on the banks of the river, creating the Kibbutz Snir, the first Israeli settlement on the Golan. In 1981, Israel annexed the Golan Heights in an illegal move unrecognised by any state but international law remained impotent. No foreign power dared intervene.

Since 2003, Israel’s confidence has increased and the Golan is now covered in scores of settlements, while dozens of hotels offering settler-made wine from the Château Golan serve as weekend getaways for Israeli city elites. A ski resort has been built on Mount Hermon. Tourist websites refer to ‘Israel’s Golan Heights’, and all local maps show it as part of Israel.

As for Banias, now emptied of residents, the site has been incorporated into one of Israel’s many ‘nature reserves’ on the Golan. Four walking trails have been neatly laid out in loops around the ancient city, its springs and its waterfalls. The souvenir shop sells T-shirts emblazoned with ‘Israeli Air Force’ and ‘Mossad’. Explanatory signs give the Israeli version of history. On the map, the basilica has become a synagogue, the Ottoman shaykh’s house has become ‘Corner Tower’, and the Syrian Officers’ Pool is simply ‘the Officers’ Pool’. The free leaflet that accompanies the entry ticket explains that Banias is now ‘a perfect place to understand the pagan world of the Land of Israel and Phoenicia’. More certainly, Banias is a great place to understand how some very modern disputes have reshaped an ancient city.