Mortal Kombat X gameplay. NetherRealm/Warner Bros. Interactive Entertainment/Wikipedia

Let’s play a game. One of the quotes below belongs to a trained soldier speaking of killing the enemy, while the other to a convicted felon describing his first murder. Can you tell the difference?

(1) ‘I realised that I had just done something that separated me from the human race and it was something that could never be undone. I realised that from that point on I could never be like normal people.’

(2) ‘I was cool, calm and collected the whole time. I knew what I had to do. I knew I was going to do it, and I did.’

Would you be surprised to learn that the first statement, suggesting remorse, comes from the American mass murderer David Alan Gore, while the second, of cool acceptance, was made by Andy Wilson, a soldier in the SAS, Britain’s elite special forces? In one view, the two men are separated by the thinnest filament of morality: justification. One killed because he wanted to, the other because he was acting on behalf of his country, as part of his job.

While most psychologically normal individuals agree that inflicting pain on others is wrong, killing others appears socially sanctioned in specific contexts such as war or self-defence. Or revenge. Or military dictatorships. Or human sacrifice. In fact, justification for murder is so pliant that the TV series Dexter (2006-13) flirted exquisitely with the concept: a sociopath who kills villainous people as a vehicle for satisfying his own dark urges.

Operating under strict ‘guidelines’ that target only the guilty, Dexter (a forensics technician) and the viewer come to believe that the kill is justified. He forces the audience to question their own moral compass by asking them to justify murder in their minds in the split second prior to the kill. Usually when we imagine directly harming someone, the image is preventive: envision a man hitting a woman; or an owner abusing her dog. Yet, sometimes, the opposite happens: a switch is flipped with aggressive, even violent consequences. How can an otherwise normal person override the moral code and commit cold-blooded murder?

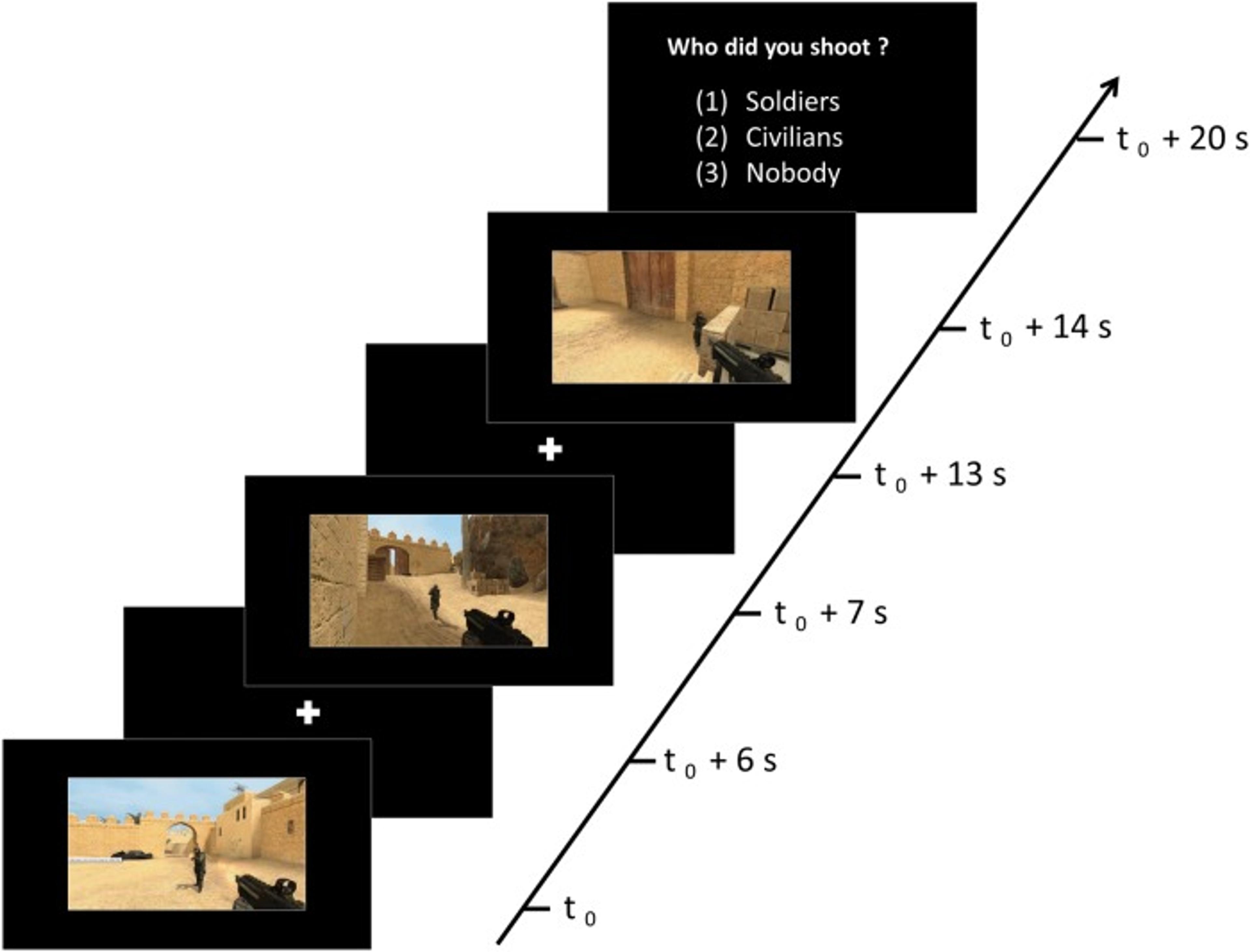

That was the question asked at the University of Queensland in Australia, in a study led by the neuroscientist Pascal Molenberghs, in which participants entered an fMRI scanner while viewing a first-person video game. In one scenario, a soldier kills an enemy soldier; in another, the soldier kills a civilian. The game enabled each participant to privately enter the mind of the soldier and control which person to execute.

Screenshot of what each participant saw

The results were, overall, surprising. It made sense that a mental simulation of killing an innocent person (unjustified kill) led to overwhelming feelings of guilt and subsequent activation of the lateral orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), an area of the brain involved in aversive, morally sensitive situations. By contrast, researchers predicted that viewing a soldier killing a soldier would create activity in another region of the brain, the medial OFC, which assesses thorny ethical situations and assigns them positive feelings such as praise and pride: ‘This makes me feel good, I should keep doing it.’

But that is not what occurred: the medial OFC did not light up when participants imagined themselves as soldiers killing the enemy. In fact, none of the OFC did. One explanation for this puzzling finding is that the OFC’s reasoning ability isn’t needed in this scenario because the action is not ethically compromising. That is to say – it is seen as justified. Which brings us to a chilling conclusion: if killing feels justified, anyone is capable of committing the act.

Since the Korean War, the military has altered basic training to help soldiers overcome existing norms of violence, desensitise them to the acts they might have to commit, and reflexively shoot upon cue. Even the drill sergeant is portrayed as the consummate professional personifying violence and aggression.

The same training takes place unconsciously through contemporary video games and media. Young children have unprecedented access to violent movies, games and sports events at an early age, and learning brutality is the norm. The media dwells upon real-life killers, describing every detail of their crime during prime-time TV. The current conditions easily set up children to begin thinking like soldiers and even justify killing. But are we in fact suppressing critical functions of the brain? Are we engendering future generations who will accept violence and ignore the voice of reason, creating a world where violence will become the comfortable norm?

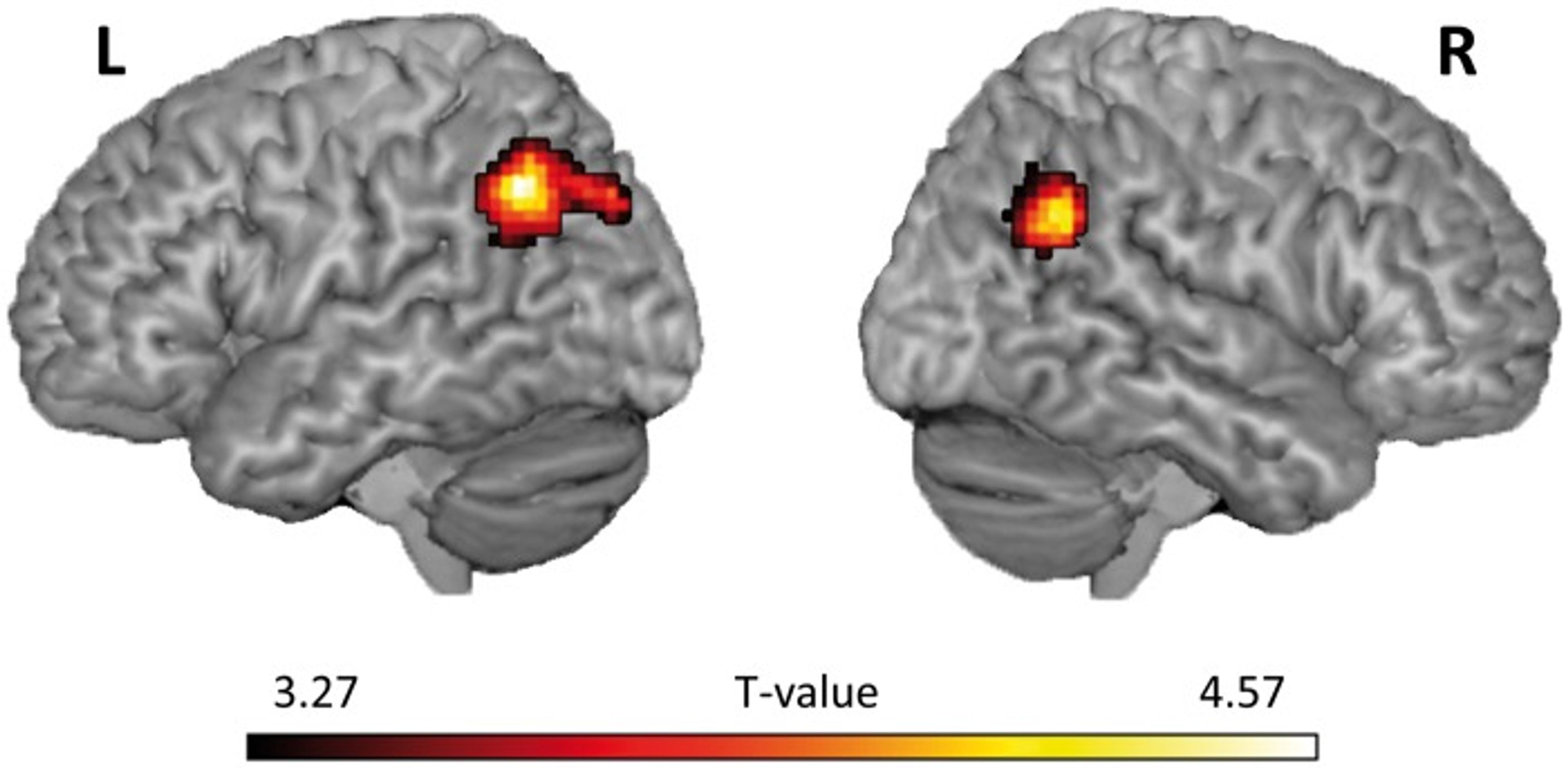

The Queensland study had something to say about this as well. When participants were viewing unjustified killings, researchers noticed increased connectivity between the OFC and an area called the temporal parietal junction (TPJ), a part of the brain that has previously been associated with empathy. They show that disrupting function of the TPJ transforms participants into psychopaths, judging any action as morally permissible and making the TPJ a critical region for empathy. Increased connectivity between the two regions suggests that the participants were actively putting themselves in the shoes of the observer, judging whether killing civilians was morally acceptable or not.

Increased connectivity between left OFC and left and right TPJ for simulating shooting a civilian

‘Emotional and physical distance can allow a person to kill his foe,’ says Lt Colonel Dave Grossman, director of the Killology Research Group in Illinois and one of the world’s foremost experts in human aggression and the roots of violence. ‘Emotional distance can be classified as mechanical, social, cultural and emotional distance.’ In other words, a lack of connection to humans allows a justified murder. The writer Primo Levi, a Holocaust survivor, believed that this was exactly how the Nazis succeeded in killing so many: by stripping away individuality and reducing each person to a generic number.

In 2016, technology and media have turned genocide viral. The video game Mortal Kombat X features spines being snapped, heads crushed and players being diced into cubes. In Hatred, gamers play as a sociopath who attempts to kill innocent bystanders and police officers with guns, flamethrowers and bombs to satisfy his hatred of humanity. Characters beg for mercy before execution, frequently during profanity-laced rants.

A plethora of studies now associate playing such games with greater tolerance of violence, reduced empathy, aggression and sexual objectification. Compared with males who have not played violent video games, males who do play them are 67 per cent more likely to engage in non-violent deviant behaviour, 63 per cent more likely to commit a violent crime or a crime related to violence, and 81 per cent more likely to have engaged in substance use. Other studies have found that engaging in cyberviolence leads people to perceive themselves as less human, and facilitates violence and aggression.

This powerful knowledge could be used to turn violence on its head. Brain-training programs could use current neuroscientific knowledge to serve up exhilarating games to train inhibition, instead of promoting anger. Creating games with the capability to alter thought patterns is itself ethically questionable and could be easily implemented to control a large population. But we’ve already gone down that road, and in the direction of violence. With today’s generation so highly dependent on technology, phasing in games from an early age that encourage tolerance could be a potent tool for building a more humane, more compassionate world.