Wikipedia

Great philosophy is not always easy. Some philosophers – Kant, Hegel, Heidegger – write in a way that seems almost perversely obscure. Others – Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Wittgenstein – adopt an aphoristic style. Modern analytic philosophers can present their arguments in a compressed form that places heavy demands on the reader. Hence, there is ample scope for philosophers to interpret the work of their predecessors. These interpretations can become classics in their own right. While not all philosophers write obscurely (eg, Hume, Schopenhauer, Russell), many do. One might get the impression that obscurity is a virtue in philosophy, a mark of a certain kind of greatness – but I’m skeptical.

To some degree, all texts need interpretation. Working out what people mean isn’t simply a matter of decoding their words, but speculating about their mental states. The same words could express quite different thoughts, and the reader has to decide between the interpretations. But it doesn’t follow that all texts are equally hard to interpret. Some interpretations might be more psychologically plausible than others, and a writer can narrow the range of possible interpretations. Why should philosophy need more interpretation than other texts?

Academics assume an advanced knowledge of their field, as well as familiarity with conceptual nuances, contemporary references, cultural norms. All this background needs filling in for those outside the tradition. When dealing with work from another time or culture, different scholars might produce different interpretations of the original. But this openness to interpretation is merely an accident of distance. The text could have been quite clear to its original readers, and with sufficient knowledge we might settle on a definitive reading. This doesn’t explain the special difficulties presented by some philosophical texts.

Maybe these difficulties exist because great philosophers operate at a higher intellectual level than the rest of us, packing their work with profound insights, complex ideas and subtle distinctions. We might need these difficult thoughts unpacked by interpreters and, since these are usually less gifted than the original authors, they might differ on the correct reading. But then, if a clear interpretation of the ideas can be provided, why didn’t the original authors do it themselves? Such a failure of communication is a defect rather than a virtue. Skilled writers shouldn’t need interpreters to patch up holes in their texts.

Another explanation focuses on the nature of philosophical enquiry. Philosophers do not simply marshal facts: they engage reflectively with a problem, raising questions, teasing out connections, investigating ideas. Readers can respond with their own questions, connections and ideas. Consequently, great works of philosophy naturally generate different interpretations. But is that because readers engage with the problem being discussed and explore their own ideas about it? Or because they engage with the problem of what the author meant and try to come up with hypotheses? Only the former is the mark of good philosophy. A work can be tentative, exploratory and suggestive without being hard to understand. The options canvassed can be set out with precision and clarity.

Perhaps obscure texts are more open to reinterpretation. Philosophy, some argue, does not progress as science does. Philosophical problems aren’t solved but continually re-explored in new contexts, and each generation returns to great works of the past and reinterprets them for its own time. So texts that are obscure are more likely to become classics, since they naturally lend themselves to reinterpretation. By contrast, unambiguous texts can soon seem sterile and dated. Personally, I am skeptical of the view that philosophy does not progress but, even if we accept it, this doesn’t justify a preoccupation with reinterpretation. If one is grappling with the same problem as an earlier writer, it might be useful to study his work, but what is gained by effectively rewriting it in light of knowledge previously unknown? Why not produce a new work that draws on the old but is not bound by it? Devotion to reinterpretation betrays a misplaced focus on philosophers rather than philosophical problems.

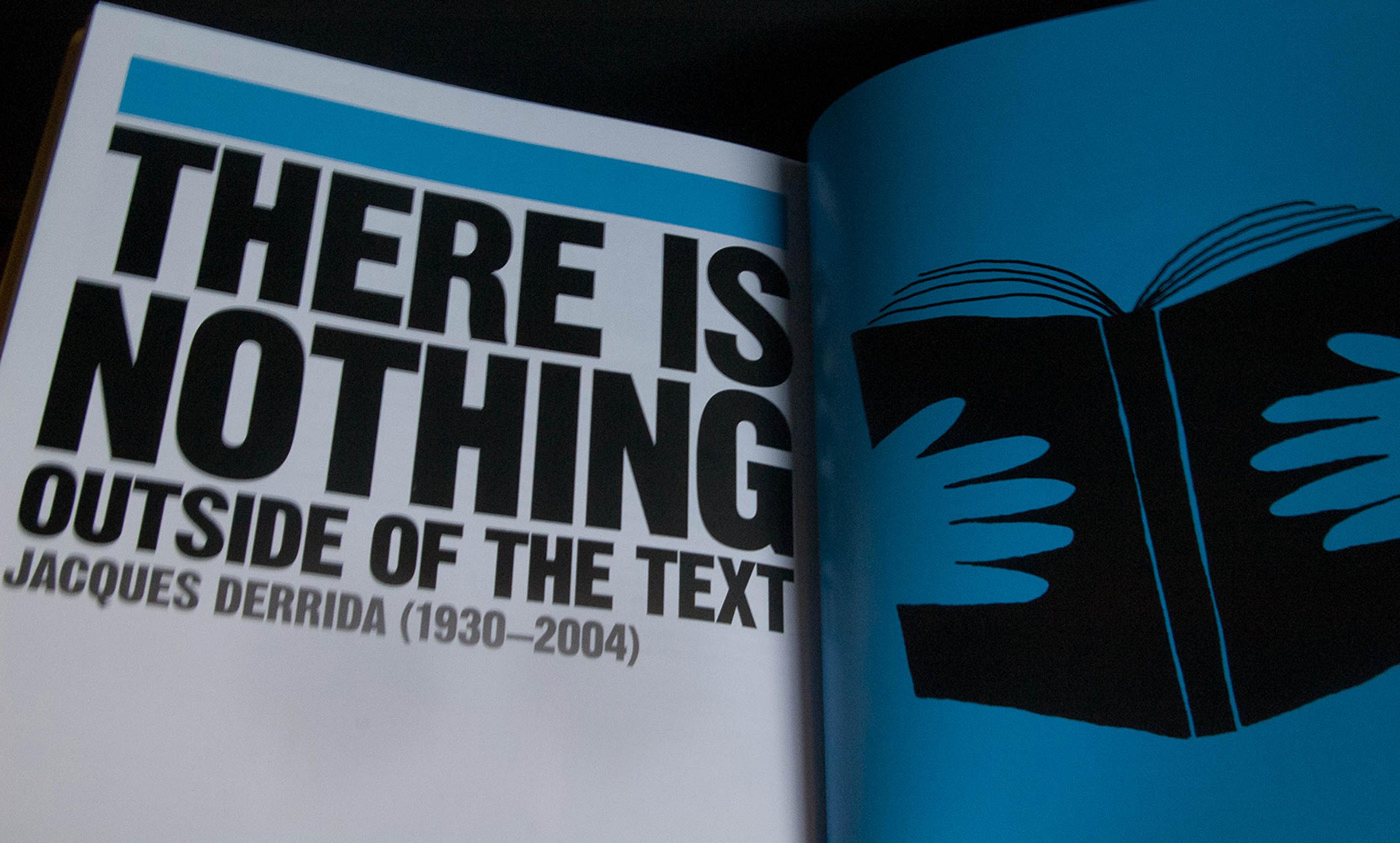

But some great philosophy is creative in a way that is incompatible with clarity. It doesn’t seek to construct precise theories; rather, it reaches out to unmapped areas of thought, where we do not yet know what techniques to employ, what concepts to use, or even what questions to ask. It is more like art than science, and it makes its own rules. It is not that such work is defective by being ambiguous; it is trying to do something that cannot be done clearly, and its aim is precisely to stimulate diverse interpretations.

This is, perhaps, the best justification for obscurity. However, it should be used with great caution. Work that respects standards of clarity can be evaluated against those standards, but how to tell if a difficult text is ground-breaking and creative or just pretentious nonsense? And how can we be sure that any good ideas it spawns were latent in the original, rather than the creation of ingenious interpreters? It’s prudent to be very suspicious of such texts; they must earn their status as serious works through a long history of intellectual fertility.

Finally, some philosophers might write obscurely because it creates an aura of profundity and mystery. This invites interpretation and scholarly attention: special effort is required to engage with the work, helping to create a cult following among scholars. The work is also harder to challenge, and criticisms can be dismissed as misinterpretations. Meanwhile, writing that is more transparent can seem less fertile or exciting, and its errors easier to spot. Not admirable, perhaps, but is it cynical to think that such motives for obfuscation sometimes play a role?

In most cases, obscurity is a defect, not a virtue, and undue concern with interpretation puts the focus on people rather than problems. It is not easy to write clearly, especially on philosophical topics, and it is risky. Clear writers stand naked before their critics, with all their argumentative blemishes visible; but they are braver, more honest and more respectful of the true aims of intellectual enquiry than ones who shroud themselves in obscurity.