Ramen heaven. From Juzo Itami’s 1985 noodle-western Tampopo. Courtesy Criterion Collection

Parents often say that they don’t mind what their children do in life just as long as they are happy. Happiness and pleasure are almost universally seen as among the most precious human goods; only the most curmudgeonly would question whether benign enjoyment is anything other than a good thing. Disagreement soon creeps in, however, if you ask whether some forms of pleasure are better than others. Does it matter whether our pleasures are spiritual or carnal, intellectual or stupid? Or are all pleasures pretty much the same?

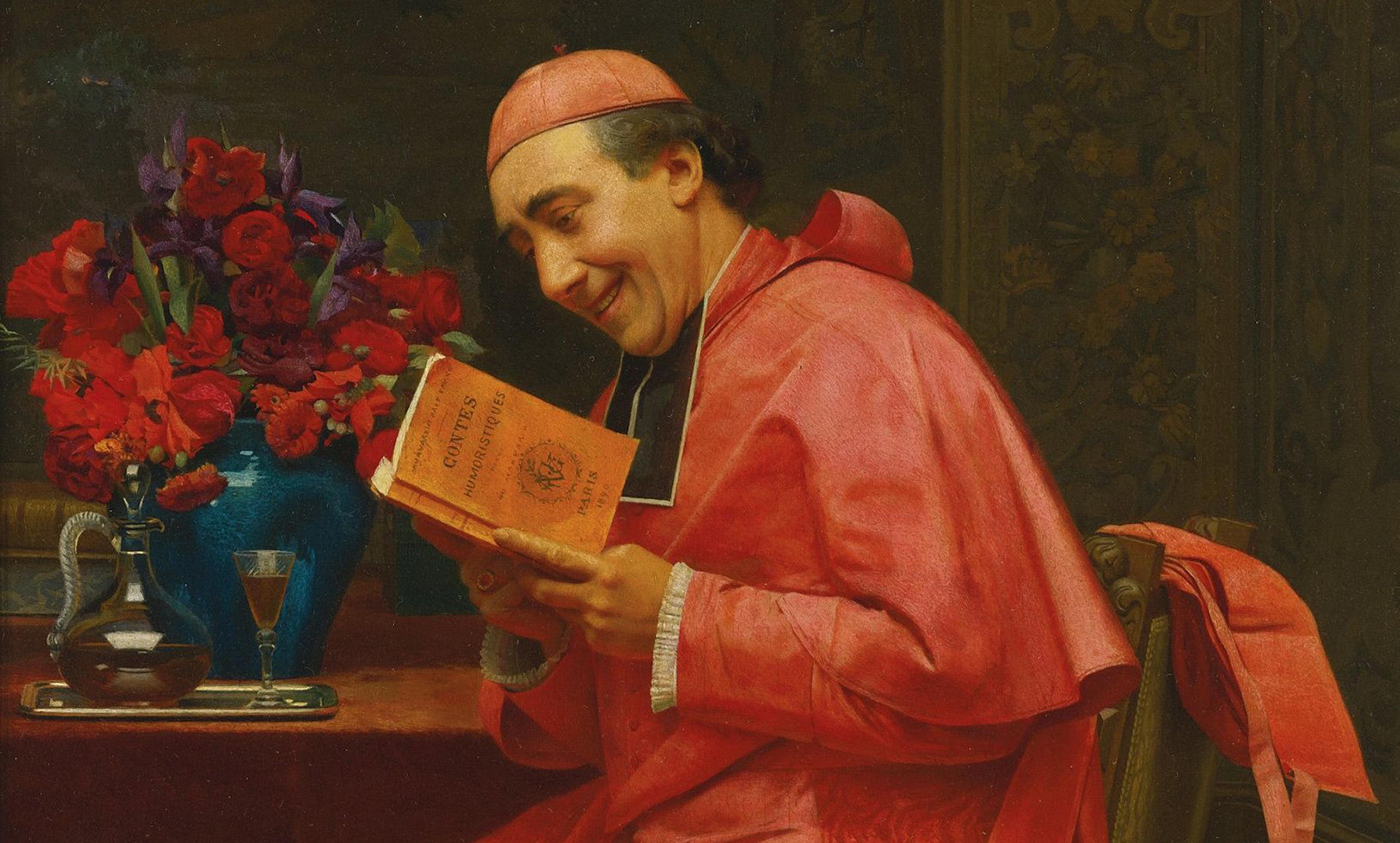

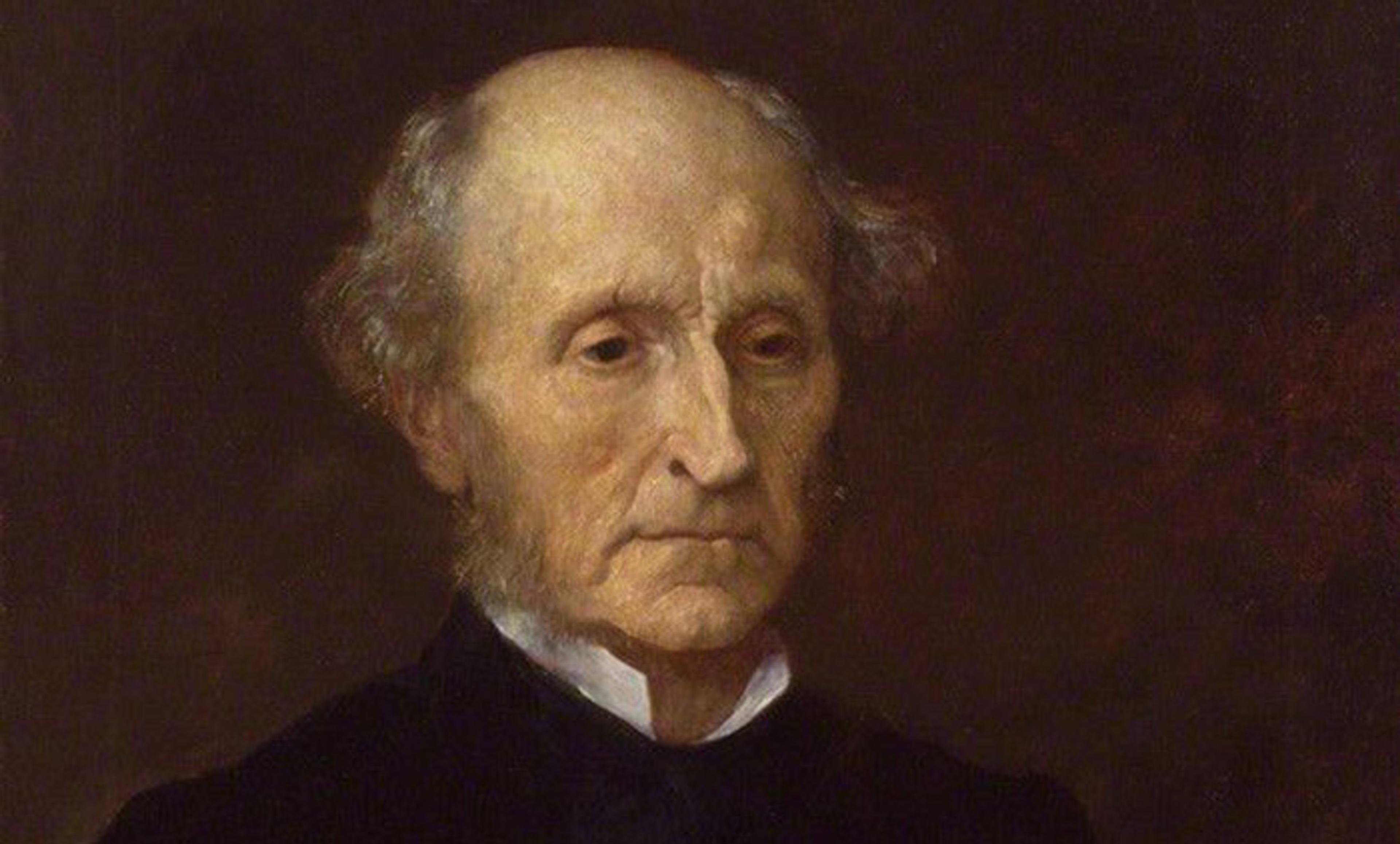

Utilitarianism, as a moral philosophy, puts pleasure at the centre of its concerns, arguing that actions are right to the extent that they increase happiness and decrease suffering, wrong to the extent that they cause the opposite. Yet even the early Utilitarians couldn’t agree about whether pleasures should be ranked. Jeremy Bentham believed that all sources of pleasure are of equal quality. ‘Prejudice apart,’ he wrote in The Rationale of Reward (1825), ‘the game of push-pin is of equal value with the arts and sciences of music and poetry.’ His protégé John Stuart Mill disagreed, arguing in Utilitarianism (1863) that: ‘It is better to be a human being dissatisfied than a pig satisfied; better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied.’

Mill argued for a distinction between ‘higher’ and lower pleasures. His distinction is difficult to pin down, but it more or less tracks the distinction between capacities thought to be unique to humans and those we share with other animals. Higher pleasures depend on distinctively human capacities, which have a more complex cognitive element, requiring abilities such as rational thought, self-awareness or language use. Lower pleasures, in contrast, require mere sentience. Humans and other animals alike enjoy basking in the sun, eating something tasty or having sex. Only humans engage in art, philosophy and so on.

Mill was certainly not the first to make this distinction. Aristotle among others thought that the senses of touch and taste were ‘servile and brutish’; the pleasures of eating were ‘as brutes also share in’ and so less valuable than those that used the more developed human mind. Yet many would continue to side with Bentham, arguing that we are really not so intellectual and high-minded as all that, and we might as well accept ourselves for the brutes that we are, shaped by biochemistry and animal drives.

The difficulty with resolving this disagreement about the kinds of pleasure is not that we struggle to agree on the right answer. It’s that we’re asking the wrong question. The entire debate assumes a clear divide between the intellectual and bodily, the human and the animal, which is no longer tenable. These days, few of us are card-carrying dualists who believe that we are made of immaterial minds and material bodies. We have plenty of scientific evidence for the importance of biochemistry and hormones in all that we do and think. Nonetheless, dualistic assumptions still inform our thinking. So, what happens if we take seriously the idea that the physical and the mental are inseparable, that we are fully embodied beings? What would it mean for our ideas about pleasure?

The dining table is a good place to start. Along with sex, food is usually considered to be the quintessential lower pleasure. All animals eat, using the senses of smell and taste. It doesn’t require any complex cognition to conclude that something is delicious. Philosophers have generally assumed that to take pleasure in eating is simply to sate a primitive desire. So, for instance, Plato believed that cookery could never be a form of art, because it ‘never regards either the nature or reason of that pleasure to which she devotes herself, but goes straight to her end’.

Plato and his successors, however, failed to appreciate something that the French food writer Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin captured pithily in The Physiology of Taste (1825): ‘Animals feed; man eats; only the man of intellect knows how to eat.’ Brillat-Savarin drew a distinction between mere animal feeding, which is the ingestion of food as fuel, and human eating, which can and should engage more than just our most basic carnal desires. Eating is a complex act. Simply gathering the ingredients takes thought, since what we buy not only requires planning but affects the wellbeing of growers, producers, animals and the planet. Cooking involves knowledge of ingredients, the application of skills, the balancing of different flavours and textures, considerations of nutrition, care for the ordering of courses or the place of the dish in the rhythm of the day. Eating, at its best, brings all these things together, adding an attentive aesthetic appreciation of the end result.

Eating illustrates how the difference between higher and lower pleasures is not what you enjoy but how you enjoy it. Wolfing down your food like a pig at a trough is a lower kind of pleasure. Preparing and eating it using the powers of reflection and attention that only a human being possesses turns it into a higher pleasure. This form of higher pleasure need not be intellectual in the academic sense. An accomplished chef might be judging the balance of flavours and textures intuitively; a home cook might simply be thinking about what his guests are most likely to enjoy. What makes the pleasure higher is that it engages our more complex human abilities. It expresses more than just the brute desire to satisfy a craving.

For every pleasure, it should not be difficult to see that the how matters more than the what. Furthermore, the highest pleasures do not merely use our distinctively human capacities, they use them for a valuable end. Someone who goes to the opera to be seen in a new dress is not experiencing the higher pleasures of music but indulging the lower pleasures of vanity. Someone who reads Dr Seuss with a careful ear for language gets a higher pleasure than someone who mechanically recites The Waste Land (1922) without any understanding of what T S Eliot was doing.

Even sex, perhaps the most primal human pleasure of all, can be appreciated in higher and lower ways. To adapt Brillat-Savarin, animals copulate, humans make love. In the intensity of sexual arousal and orgasm, it might not seem that our evolved human capacities are doing much work. But sex is highly contextual, and changes its nature depending on whether it is part and parcel of a genuine relationship between two human beings, however brief, or merely the satisfaction of a brute urge.

Mill was therefore right to believe that pleasures come in higher and lower forms but wrong to think that we could distinguish them on the basis of what we take pleasure in. What matters is how we enjoy them, which means that higher and lower pleasures are not two discrete categories but form a continuum. I think the persistence of the bogus form of the higher/lower pleasures distinction is a result of the fact that some things are more obviously amenable to richer appreciation than others. Art is typically enjoyed in mind-engaging ways, food all too often consumed in an animalistic one. This has led us to mistake association for identity.

The mistake also betrays a false view of human nature, which sees our intellectual or spiritual aspects as being what truly makes us human, and our bodies as embarrassing vehicles to carry them. When we learn how to take pleasure in bodily things in ways that engage our hearts and minds as well as our five senses, we give up the illusion that we are souls trapped in mortal coils, and we learn how to be fully human. We are neither angels above bodily pleasures nor crude beasts slavishly following them, but psychosomatic wholes who bring heart, mind, body and soul to everything we do.

Julian Baggini will be discussing his upcoming book and first global overview of philosophy, ‘How The World Thinks’, at this year’s HowTheLightGetsIn festival, a two-day philosophy and music festival in London, September 2018.