Photo by Mihai Surdu/Unsplash

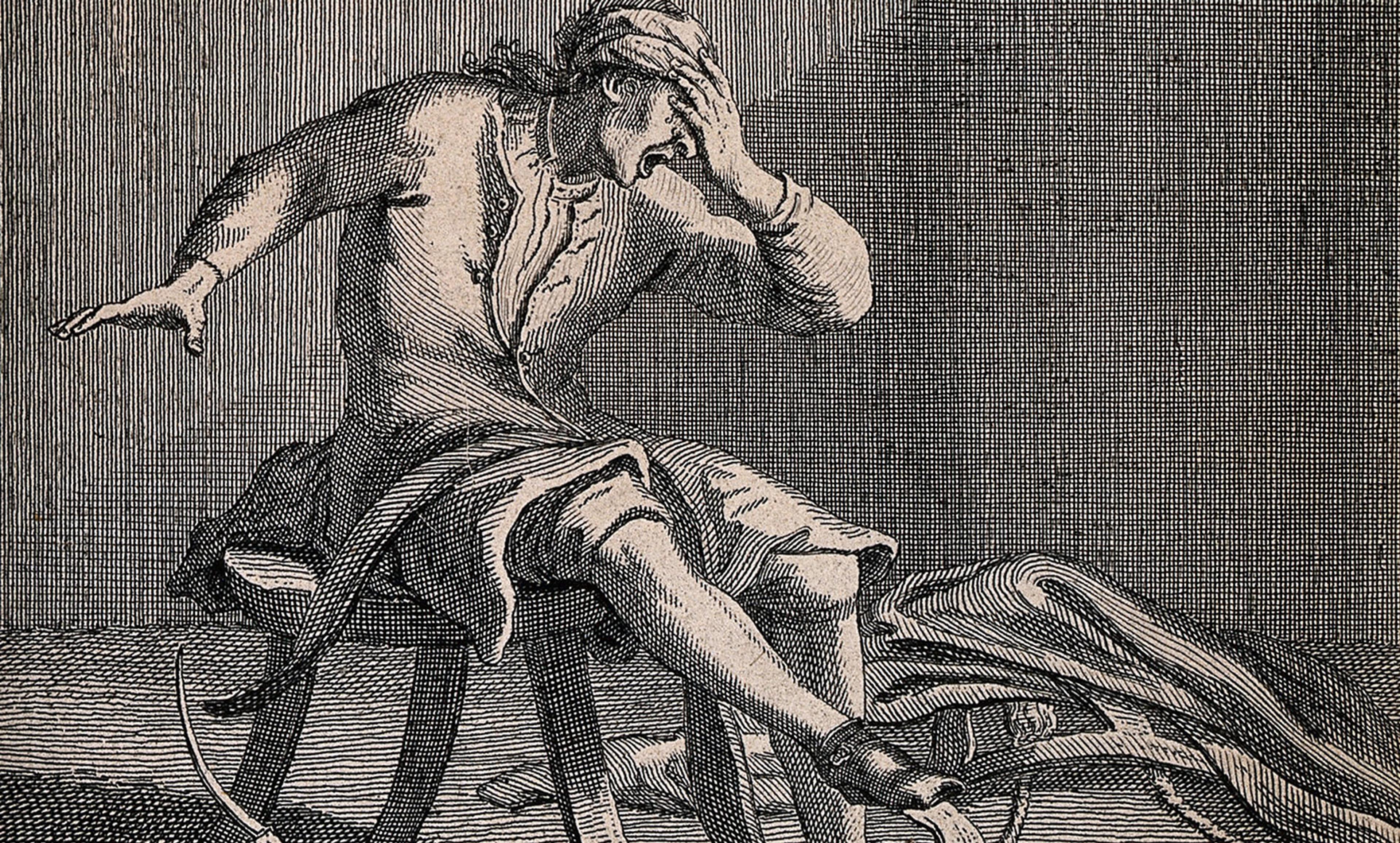

What, exactly, is boredom? It is a deeply unpleasant state of unmet arousal: we are aroused rather than despondent, but, for one or more reasons, our arousal cannot be met or directed. These reasons can be internal – often a lack of imagination, motivation or concentration – or external, such as an absence of environmental stimuli or opportunities. We want to do something engaging, but find ourselves unable to do so and, more than that, are frustrated by the rising awareness of this inability.

Awareness, or consciousness, is key, and might explain why animals, if they do get bored, generally have higher thresholds for boredom. In the words of the British writer Colin Wilson: ‘most animals dislike boredom, but man is tormented by it’. In both man and animal, boredom is induced or exacerbated by a lack of control or freedom, which is why it is so common in children and adolescents, who, in addition to being chaperoned, lack the mind furnishings – the resources, experience and discipline – to mitigate their boredom.

Let’s look more closely at the anatomy of boredom. Why is it so damned boring to be stuck in a departure lounge while our flight is increasingly delayed? We are in a state of high arousal, anticipating our imminent arrival in a novel and stimulating environment. True, there are plenty of shops, screens and magazines around, but we’re not really interested in them and, by dividing our attention, they serve only to exacerbate our boredom. To make matters worse, the situation is out of our control, unpredictable (the flight could be further delayed, or even cancelled) and inescapable. As we check and re-check the monitor, we become painfully aware of all these factors and more. And so here we are, caught in transit, in a high state of arousal that we can neither engage nor escape.

If we really need to catch our flight, maybe because our livelihood or the love of our life depends on it, we will feel less bored (although more anxious and annoyed) than if it had been a toss-up between travelling and staying at home. In that much, boredom is an inverse function of perceived need or necessity. We might get bored at the funeral of an obscure relative but not at that of a parent or sibling.

So far so good, but why exactly is boredom so unpleasant? The 19th-century German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer argued that, if life were intrinsically meaningful or fulfilling, there could be no such thing as boredom. Boredom, then, is evidence of the meaninglessness of life, opening the shutters on some very uncomfortable feelings that we normally block out with a flurry of activity or with the opposite feelings. This is the essence of the manic defence, which consists in preventing feelings of helplessness and despair from entering the conscious mind by occupying it with opposite feelings of euphoria, purposeful activity and omnipotent control – or, failing that, any feelings at all.

In Albert Camus’s novel The Fall (1956), Clamence reflects to a stranger:

I knew a man who gave 20 years of his life to a scatterbrained woman, sacrificing everything to her, his friendships, his work, the very respectability of his life, and who one evening recognised that he had never loved her. He had been bored, that’s all, bored like most people. Hence he had made himself out of whole cloth a life full of complications and drama. Something must happen – and that explains most human commitments. Something must happen, even loveless slavery, even war or death.

People who suffer from chronic boredom are at higher risk of developing psychological problems such as depression, overeating, and alcohol and drug misuse. A study found that, when confronted with boredom in an experimental setting, many people chose to give themselves unpleasant electric shocks simply to distract from their own thoughts, or lack thereof. Out in the real world, we expend considerable resources on combatting boredom. The value of the global entertainment and media market is set to reach $2.6 trillion by 2023, and entertainers and athletes are afforded ludicrously high levels of pay and status. The technological advances of recent years have put an eternity of entertainment at our fingertips, but this has made matters only worse – in part, by removing us further from our here and now. Instead of feeling sated and satisfied, we are desensitised and in need of ever more stimulation – ever more war, ever more gore, and ever more hardcore.

The good news is that boredom can also have upsides. Boredom can be our way of telling ourselves that we are not spending our time as well as we could, that we should be doing something more enjoyable, more useful, or more fulfilling. From this point of view, boredom is an agent of change and progress, a driver of ambition, shepherding us out into larger, greener pastures.

But even if we are one of those rare people who feels fulfilled, it is worth cultivating some degree of boredom, insofar as it provides us with the preconditions to delve more deeply into ourselves, reconnect with the rhythms of nature, and begin and complete highly focused, long and difficult work. As the British philosopher Bertrand Russell put it in The Conquest of Happiness (1930):

A generation that cannot endure boredom will be a generation of little men, of men unduly divorced from the slow processes of nature, of men in whom every vital impulse slowly withers as though they were cut flowers in a vase.

In 1918, Russell spent four and a half months in Brixton prison for ‘pacifist propaganda’, but found the bare conditions congenial and conducive to creativity:

I found prison in many ways quite agreeable … I had no engagements, no difficult decisions to make, no fear of callers, no interruptions to my work. I read enormously; I wrote a book, Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy … and began the work for Analysis of Mind … One time, when I was reading Strachey’s Eminent Victorians, I laughed so loud that the warder came round to stop me, saying I must remember that prison was a place of punishment.

Of course, not everyone is a Bertrand Russell. How might we, mere mortals, best cope with boredom? If it is, as we have established, an awareness of unmet arousal, we can minimise boredom by: avoiding situations over which we have little control; eliminating distractions; motivating ourselves; expecting less; putting things into their proper perspective (realising how lucky we really are); and so on.

But rather than fighting a constant battle against boredom, it is easier and much more productive to actually embrace it. If boredom is a window on to the fundamental nature of reality and, by extension, on to the human condition, then fighting boredom amounts to pulling back the curtains. Yes, the night is pitch-black, but the stars shine all the more brightly for it.

For just these reasons, many Eastern traditions encourage boredom, seeing it as the path to a higher consciousness. Here’s one of my favourite Zen jokes:

A Zen student asked how long it would take to gain enlightenment if he joined the temple.

‘Ten years,’ said the Zen master.

‘Well, how about if I work really hard and double my effort?’

‘Twenty years.’

So instead of fighting boredom, go along with it, entertain it, make something out of it. In short, be yourself less boring. Schopenhauer said that boredom is but the reverse side of fascination, since both depend on being outside rather than inside a situation, and one leads to the other.

Next time you find yourself in a boring situation, throw yourself fully into it – instead of doing what we normally do, which is to step further and further back. If this feels like too much of an ask, the Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh advocates simply appending the word ‘meditation’ to whatever activity it is that you find boring, for example, ‘standing-in-line meditation’.

In the words of the 18th-century English writer Samuel Johnson: ‘It is by studying little things that we attain the great art of having as little misery and as much happiness as possible.’