Michael Fleshman/Flickr

As the United States enters into another presidential season, the media is once again covering the election as a horse race. CNN, MSNBC, and Fox News constantly discuss the latest polling debate, generate controversies in order to boost ratings, and wonder how particular candidates will lead when events such as the Paris bombings happen again. This personality-driven coverage credits presidents when things go right for the nation and blames them when they don’t. In other words, it ignores the structural limitations of US politics. Yes, the president is the most important single individual in US political life, but the holder of that office cannot overturn a Supreme Court decision, break a Senate filibuster, or force the House to pass a budget. Power in the US is unusually decentralised for a strong nation. The fact that there are so many levers to that power should undermine narratives of presidential leadership. Alas, such complexity would not help television ratings.

We can see how damaging this focus on presidential leadership is on the activism of the citizenry if we look at the aftermath of the 2008 election of Barack Obama. This was a remarkable election not only because Obama became the first African American elected to the nation’s highest office. Obama won in 2008 partly because so many people believed his ‘hope and change’ narrative. They thought that, if they elected Obama, progressive change would transform the US. What they found out was that a) presidents don’t lead social movements, and b) conservatives could undermine the president’s agenda by protests and expressions of anger in a variety of media.

By the 2010 midterm elections, the shine was off the Obama administration. There was a lot of bitterness on the left that Obama had not created a single-payer healthcare system, that he had not closed Guantánamo Bay, that he had not prosecuted the banks for causing the financial crisis, and that we still had troops in the Middle East. But the fact is, Obama could not have changed any of these things. Too many other people had the power of veto.

Maybe the problem is that we need to change the way we think about power and change. Instead of just waiting for a president to provide leadership, maybe we should go to the streets, the online forums and the rallies to demand the change we want to see. Certainly any understanding of US history demonstrates that this is actually how most change takes place. From the thousands of striking workers in 1934 who helped to convince the Roosevelt Administration to support the right to collective bargaining, to the Civil Rights movement’s decade of organising which finally convinced Lyndon Johnson to fight for a meaningful Civil Rights bill in 1964, activism can often lead presidents instead of the other way around. People organise, and then politicians respond. Electing the right candidate is an important part of that change, but it’s not the only part. We need to recognise and act upon that.

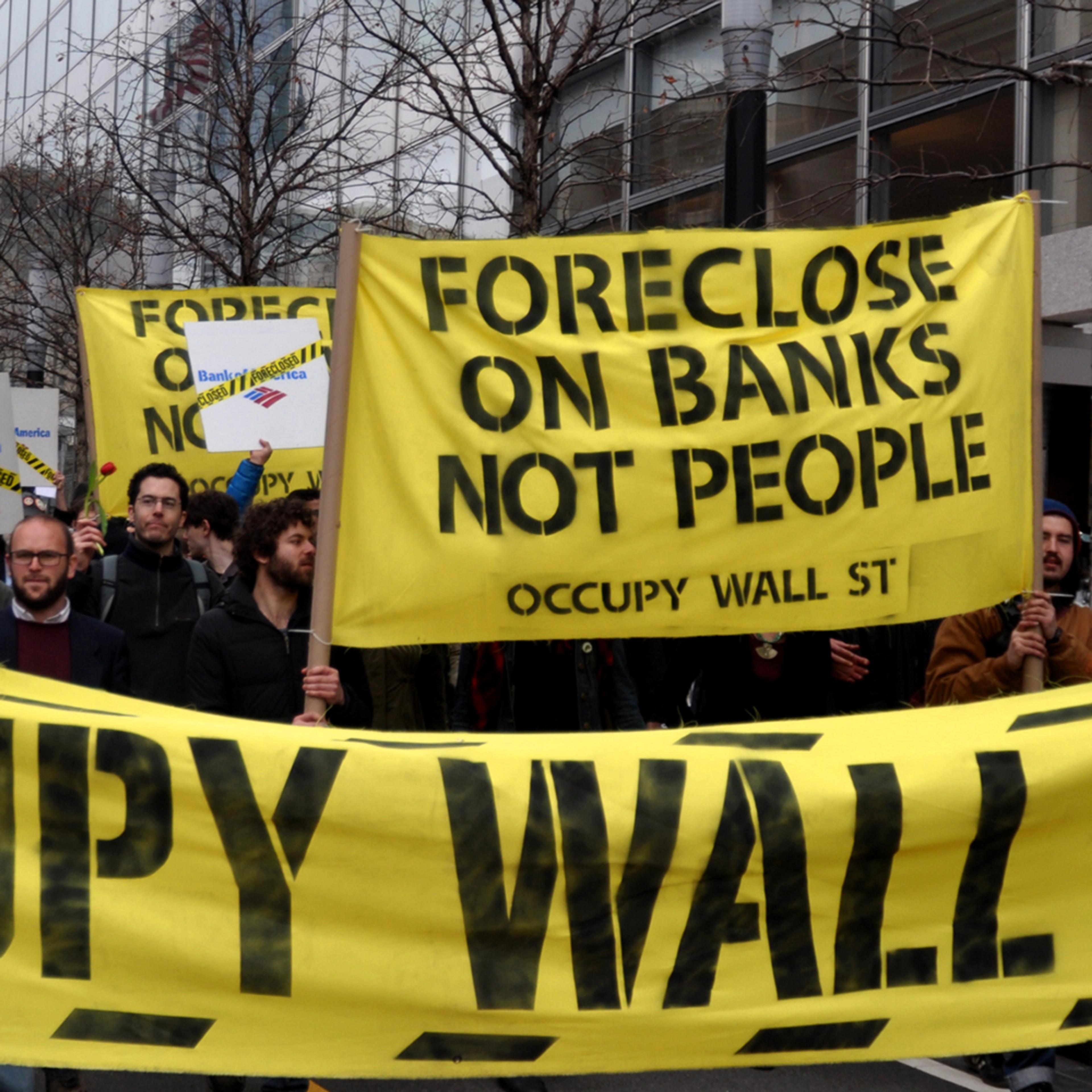

In fact, we are seeing an important upsurge in protests throughout the US and can clearly trace changes in the political parties in response. Beginning with the Occupy movement in 2011 and continuing through the Black Lives Matter movement, the Fight for $15 campaign among fast‑food workers, and the recent protests on US college campuses over racial discrimination, Americans are increasingly aware that they need to go to the streets to fight for their rights. By protesting, they can gain media attention and force politicians to move toward their position. For example, the 350.org climate change movement’s protests recently won a major victory when Obama refused to approve the Keystone XL Pipeline. Even conservative states such as Arkansas and Nebraska are approving minimum-wage increases in order to fight income inequality. These are major victories – both in themselves, and because they seem to be pulling the Democratic Party to the left, as the popularity of Bernie Sanders helps to demonstrate.

If anything, the case for grassroots protest is even stronger when examining the Republicans. Despite derisive responses to the rise of the Tea Party as an ‘AstroTurf’ movement orchestrated by wealthy backers, its growth has tapped into real popular discontent. The Tea Party has driven the Republican Party significantly to the right, its politicians fearful that they might anger their core supporters. Donald Trump and Ben Carson are not leading the Republican base. The Republican base is demanding candidates such as Trump and Carson. They are angry at how the nation has turned and have organised against it. For many Americans who are not right-wingers, the rise of this new hyper-conservative politics is frightening. But it should teach us a valuable lesson about the power of campaigners.

The real lesson we should take from presidential campaigns, no matter what our political perspective, is that people organising for change matters. It’s natural to think of presidents as leaders, and to some extent they are. But they are also political beings and they respond to pressure. The rightward drift of the Republican Party and leftward drift of the Democratic Party are both evidence of this statement. The more we understand this, the less we will buy into cheap media narratives of presidential leadership and understand that change ultimately resides in our actions.