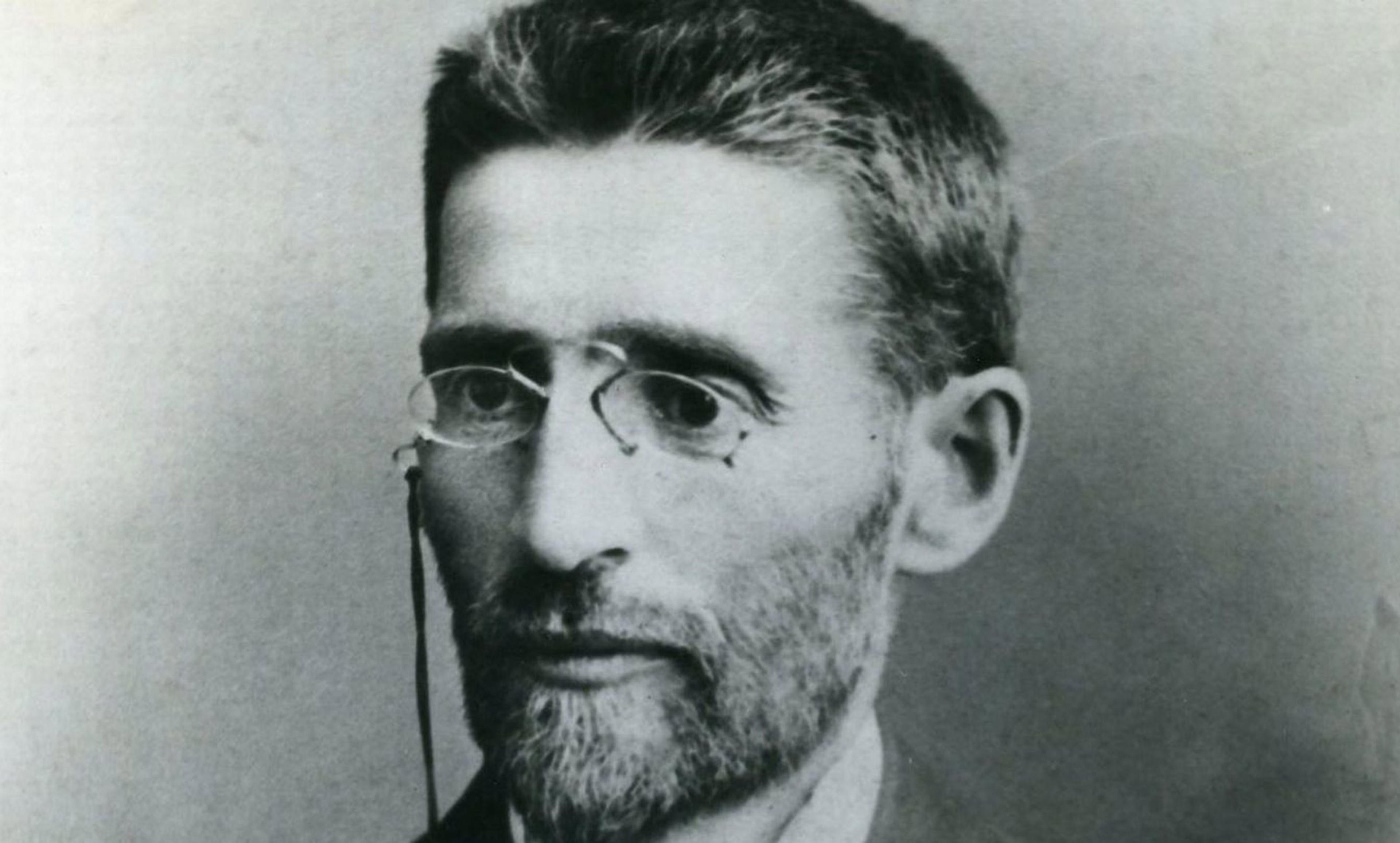

Eliezer Ben-Yehuda in 1905. Photo courtesy Wikipedia

In a Jewish section of Jerusalem, in 1885, a young couple, Eliezer and Devora Ben-Yehuda, were fearful for their child: they were rearing him in Hebrew, an unheard-of idea. They had taken in a wet-nurse, a dog and a cat; the nurse agreed to coo in Hebrew, while the dog and the cat – one male, the other female – would give the infant Itamar an opportunity to hear Hebrew adjectives and verbs inflected for gender. All other languages were to be silenced.

When Itamar turned three, however, he had still not uttered a word. Family friends protested. Surely this mother-tongue experiment would produce an imbecile. And then, the story goes, Itamar’s father marched in and upon finding the boy’s mother singing him a lullaby in Russian, flew into a rage. But then he fell silent, as the child was screaming: ‘Abba, Abba!’ (Daddy, Daddy!) Frightened little Itamar had just begun the reawakening of Hebrew as a mother tongue.

This is how I heard the story (embroidered, no doubt, by time) when I interviewed Itamar’s last living sister, Dola, for my BBC documentary ‘Tongue of Tongues’ in 1989.

As a young man in Russia, Eliezer Ben-Yehuda (born Perlman) had a far more modest dream: Jewish cultural rebirth. Groups of eastern European Jews, intensively schooled in the Bible and the Talmud in the traditional religious way, were beginning to explore a new, secular Jewish identity, built on reimagining their past and at the same time forging a ‘modernised’ Hebrew to acquaint fellow Jews with contemporary arts and sciences. Hebrew novels started appearing in Warsaw and Odessa, along with periodicals, newspapers, textbooks and encyclopaedias. They variously called their project haskalah (‘enlightenment’) or tehiyah (‘reawakening’).

Cultural renaissance, of course, was a rallying cry across 19th-century Europe, driven by a romantic reverence for a simpler or more glorious national past and, especially after 1848, by tumultuous struggles for ethnic and linguistic self-determination. The driving forces and goals were various and complex. Some, such as ennui in the soulless big city or the mobilisation of the masses through literacy, were modern; others were rooted in old ethnic identities or a respect for the vernacular in the arts and religion. The words and ways of the peasantry had a particular ring of authenticity for many nationalistic intellectuals, often neurotically out of touch (as Elie Kedourie and Joshua Fishman have documented) with the masses they aspired to lead. These sophisticated intellectuals were equally enchanted by childhood and the child’s access to truth and simplicity, as celebrated by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, William Blake and William Wordsworth.

To the vast majority of Jews, Hebrew language and Hebrew culture felt passé – pious, outmoded, arcane. The future, as they saw it, lay with English, German and Russian, and with the education, earning power and passport to assimilation that these languages promised. Migration to the West was on many minds. The young Ben-Yehuda was well aware of this. If current trends continued, he believed that his generation might well be the last erudite enough to understand its Jewish literary heritage.

But what kind of cultural ‘liberation’ could Jewish nationalists hope for? The Jews had no territory of their own, and a Jewish state, even Jewish autonomy, seemed a fantasy. (Zionism as a mass movement was still a generation in the future.) Nor was there a Hebrew-speaking peasantry or a Hebrew folk heritage to turn to for authenticity, or so it seemed. Hebrew was incorrigibly adult, stuffy. There was Yiddish, of course, the vernacular of most European Jews in the 19th century, but they generally considered it undignified, comic, a language without a grammar, a mishmash.

Then, in 1878, as Europe was toasting Bulgaria’s triumph against the Ottomans, the 19-year-old Ben-Yehuda had his epiphany. As he recalled years later in his memoirs: ‘The heavens opened … and I heard a mighty voice within me calling: “The rebirth of the Jews and their language on ancestral soil!”’ What if Jews could build a modern way of life in the Holy Land – raising their children to speak the old language?

Ben-Yehuda wanted great literature to be preserved down the generations. But to speak in order to read? Today, it sounds back-to-front, but in the 19th century it would have seemed quite reasonable. The trouble was that no child had used Hebrew as a mother tongue in close to 2,000 years. Thinking logically, Ben-Yehuda reasoned that a new mother tongue would need a willing mother: and so he found one, in an intellectual young woman named Devora Jonas, raised like him in Yiddish and Russian, and with only the barest knowledge of Hebrew. (Intensive textual study was traditionally reserved for young men.) No matter – they would marry and she would learn. In 1881, the young couple set sail for the Holy Land, pledging to set up the first secular, ‘progressive’ household in the pious city of Jerusalem, and to communicate with each other (and eventually, their children) only in Hebrew.

Speaking Hebrew was actually nothing new in itself; it had long been a lingua franca between Yiddish-, Ladino- and Arabic-speaking Jewish traders (and refugees). The markets of the Holy Land had resonated with Hebrew for hundreds of years. But a pidgin is not a mother tongue. Ben-Yehuda was a born philologist; he plucked words from ancient texts and coined his own, hoping one day to launch Hebrew’s answer to the Oxford English Dictionary. The birth of Itamar gave him an opportunity to put his experiment with Hebrew to the test. Could they rear the boy in Hebrew? Could they shield him from hearing other tongues? And, just as critical, could the family be a model for others?

Devora’s limited Hebrew was presumably sufficient for a three-year-old, but, like immigrant mothers everywhere, she eventually learned fluent Hebrew from her children, thereby demonstrating the two-way validity of the model. Ben-Yehuda, however, won the acclaim. ‘Why does everyone call him the Father of Modern Hebrew?’ sniffed the author S Y Agnon. ‘The people needed a hero,’ a politician wryly quipped, ‘so we gave them one.’ Ben-Yehuda’s political vision and scholarly toil complemented the physical toil by which the Zionist pioneers made their return to the Holy Land sacred.

Many more pieces had to fall into place in subsequent years to turn a language of books into a stable mother tongue for an entire society – some carefully laid, others dropping from heaven. But amid the waves of revolutionary-minded migrants deeply schooled in traditional texts, the developing demographics, economics and institutions of a new nation, the nationalistic fervour, and a lot of sheer desperation, we should not forget Hebrew’s very special version of the romance of a child’s talk.

The Story of Hebrew by Lewis Glinert is out now with Princeton University Press.