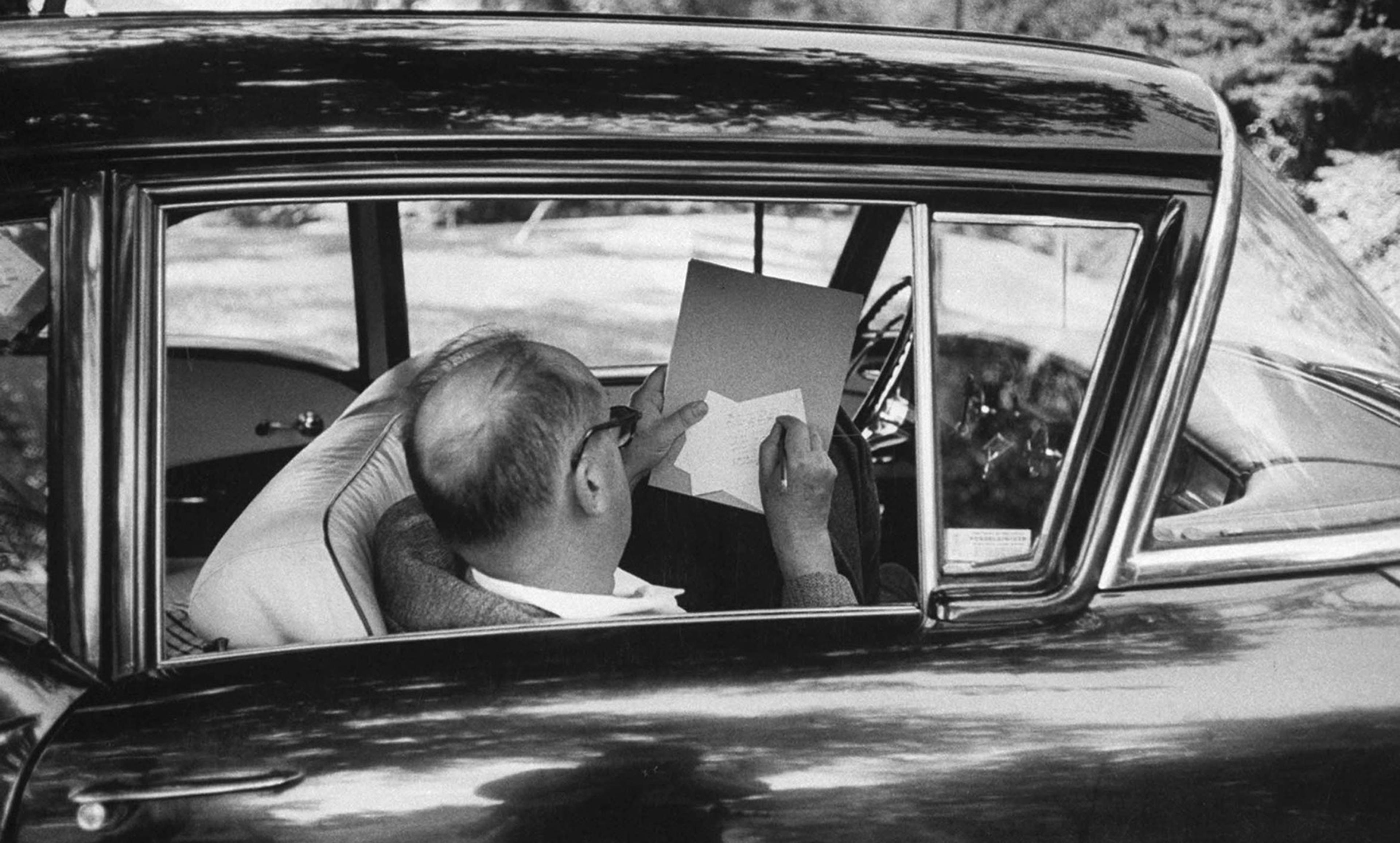

Non-native tongue. Vladimir Nabokov pictured writing notes in his car in Ithaca, New York, in 1958. Photo by Carl Mydans/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty

Learning a new language is a lot like entering a new relationship. Some will become fast friends. Others will hook their arms with calculus formulas and final-exam-worthy historical dates, and march right out of your memory on the last day of school. And then sometimes, whether by mere chance or as a consequence of a lifelong odyssey, some languages will lead you to the brink of love.

Those are the languages that will consume you – all of you – as you do everything to make them yours. You dissect syntax structures. You recite conjugations. You fill notebooks with rivers of new letters. You run your pen over their curves and cusps again and again, like you would trace your fingers over a lover’s face. The words bloom on paper. The phonemes interlace into melodies. The sentences taste fragrant, even as they tumble awkwardly from your mouth like bricks built of foreign symbols. You memorise prose and lyrics and newspaper headlines, just to have them at your lips after the sun dips and when it dawns again.

Verbs after adverbs, nouns after pronouns, your relations deepen. Yet, the closer you get, the more aware you become of the mirage-like void between you. It’s vast, this void of knowledge, and you need a lifetime to traverse it. But you have no fear, since the path to your beloved gleams with curiosity and wonder that is almost urgent. What truths will you uncover amid the new letters and the new sounds? About the world? About yourself?

As with all relationships, the euphoria wears off eventually. With your wits regained, you keep dissecting and memorising, listening and speaking. Your accent is incorrigible. Your mistakes are inescapable. The rules are endless, as are the exceptions. The words – grace; bless you; once upon a time – have lost their magic. But your devotion to them, your need for them is more earnest than ever. You have wandered too far from home to turn back now. You feel committed and vulnerable, trusting of their benevolence. On the occasion of your renewed vows, the language comes bearing gifts of inspiration and connection – not only to new others, but to a new you.

Many renowned writers have revelled in the gifts of their non-native tongues. Vladimir Nabokov, for instance, had been living in the United States for only a few years before he wrote Lolita (1955): a work that has been hailed as ‘a polyglot’s love letter to language’ and had him called a ‘master of English prose’. The Irishman Samuel Beckett wrote in French to escape the clutter of English. The Canadian Yann Martel found success writing not in his native French, but in English – a language that he says provides him with ‘a sufficient distance to write’. This distance, observes the Turkish novelist Elif Shafak of writing in her non-native English, leads her closer to home.

When Haruki Murakami sat at his kitchen table to write his first novel, he felt like his native Japanese was getting in the way. His thoughts would rush out of him like out of a ‘barn crammed with livestock’, as he put it in 2015. Then he tried writing in English, with limited vocabulary and simple syntax at his hands. As he translated (‘transplanted’, he calls it) his compact English sentences ‘stripped of all extraneous fat’ into Japanese, a distinctly unadorned style was born that decades later became synonymous with his worldwide success. When the Pulitzer Prize-winning author Jhumpa Lahiri started writing in Italian – a language she had been loving and learning for years – she felt like she was writing with her weaker hand. She was ‘exposed’, ‘uncertain’ and ‘poorly equipped’. Yet, she writes in 2015, she felt light and free, protected and reborn. Italian made her rediscover why she writes – ‘the joy as well as the need’.

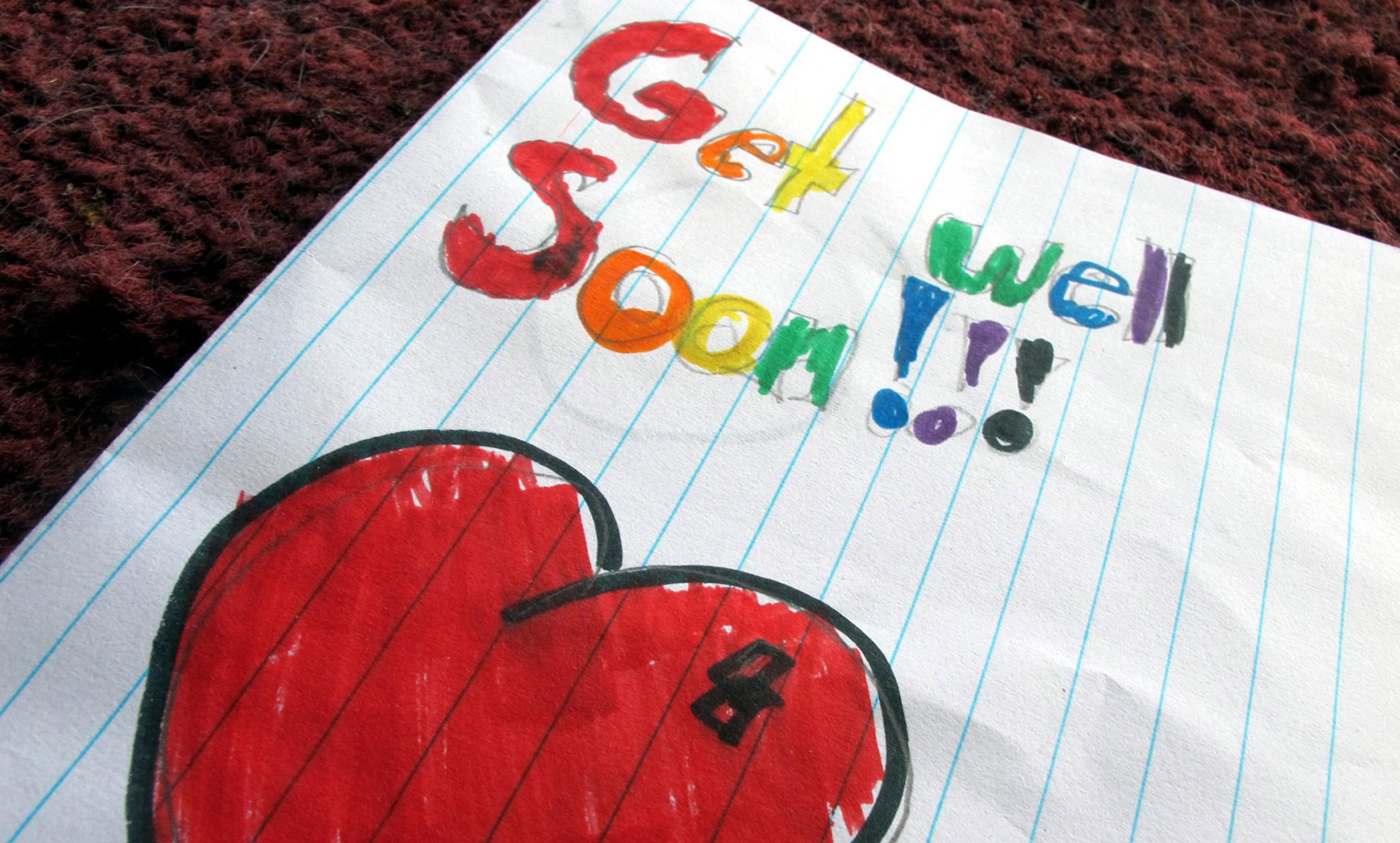

But affairs of the heart rarely leave any witnesses untouched. Including our mother tongues. My grandmother has a collection of letters that I wrote to her after I left Armenia for Japan. Once in a while, she takes out the stack of envelopes with Japanese stamps that she keeps next to her passport, and reads through them. She knows all the words by heart, she insists with pride. One day, as we sit across each other with a screen and a continent between us, grandma shakes her head.

Something changed, she tells me ominously, skimming my sentences through her oversized glasses. With each letter, something kept changing, she says.

Of course something changed, grandma, I tell her. I moved to Japan. I hit puberty. I…

No, she laments with teacher’s remorse, your writing changed. First, it was the odd spelling mistake here and there. Then, the verbs and the nouns would pop up in wrong places.

Silence settles between us. I keep my eyes on the procession of English letters on my keyboard.

It’s nothing dramatic, she tells me, mostly to console herself, but enough for me to hold my breath every time I stumbled on errors that weren’t there before.

She opens another envelope.

Oh, and then, she exclaims, the punctuation! All of a sudden, there were too many commas. Then a single dot at the end of your sentences.

She lifts her glasses on top of her puff of white hair and begins to wrap her treasures back into my late grandfather’s handkerchief.

The last one that you sent me, she says with a defeated simper, that’s when everything changed. You wrote in our letters, you used our words, but it no longer sounded Armenian.

The truth is that entering an intimate relationship with a new language often colours everything. Our eyes expect the new words. Our ears habituate to the new sounds. Our pens memorise the new letters. While the infatuation takes over our senses, the language’s anatomy etches into our brains. Neural pathways are laid, connections are formed. Brain networks integrate. Grey matter becomes denser, white matter gets strengthened. Then, splatters of the new hues begin to show up in letters to grandma.

Linguists call this ‘second language interference’, when the new language interferes with the old language, like a new lover rearranging the furniture of your bedroom, as if to say – this is how things will be done around here from now on. Somehow, writing exposes this interference (this betrayal, as grandma saw it) more than speaking ever could. Maybe because, when spoken, our words are at the mercy of our facial expressions and the range of our timbres, as the French author Guy de Maupassant observed; ‘But black words on a white page are the soul laid bare.’

Although it has been two decades since I last wrote in Armenian, grandma shouldn’t have wept over my dying mother tongue. Mother tongues, like any other first love, are very hard to forget. They are loyal and forgiving. Even when our speech shrivels and our writing is plagued with errors. Even when our native letters appear foreign and our native sounds ring forsaken. After all, our mother tongues raised us. They knew us when we didn’t know ourselves. They watched us learn to speak, to write, to reason. They taught us to love and to grieve. They showed us the rules and the exceptions. They know they’ll echo within our walls long after we become guests in our own homes: from the way we will combine the new words, to the way we will whisper the old prayers. So they watch over us quietly, unfretfully, as we drift away to another’s arms. There, in a juxtaposition of ignorance and wonder, constraint and freedom, awe and reverence, frustration and joy, they will see their writers exercise what Murakami calls their inherent right – ‘to experiment with the possibilities of language’. There, in the throes of belonging and nonbelonging, they will find their sons and daughters finding themselves.