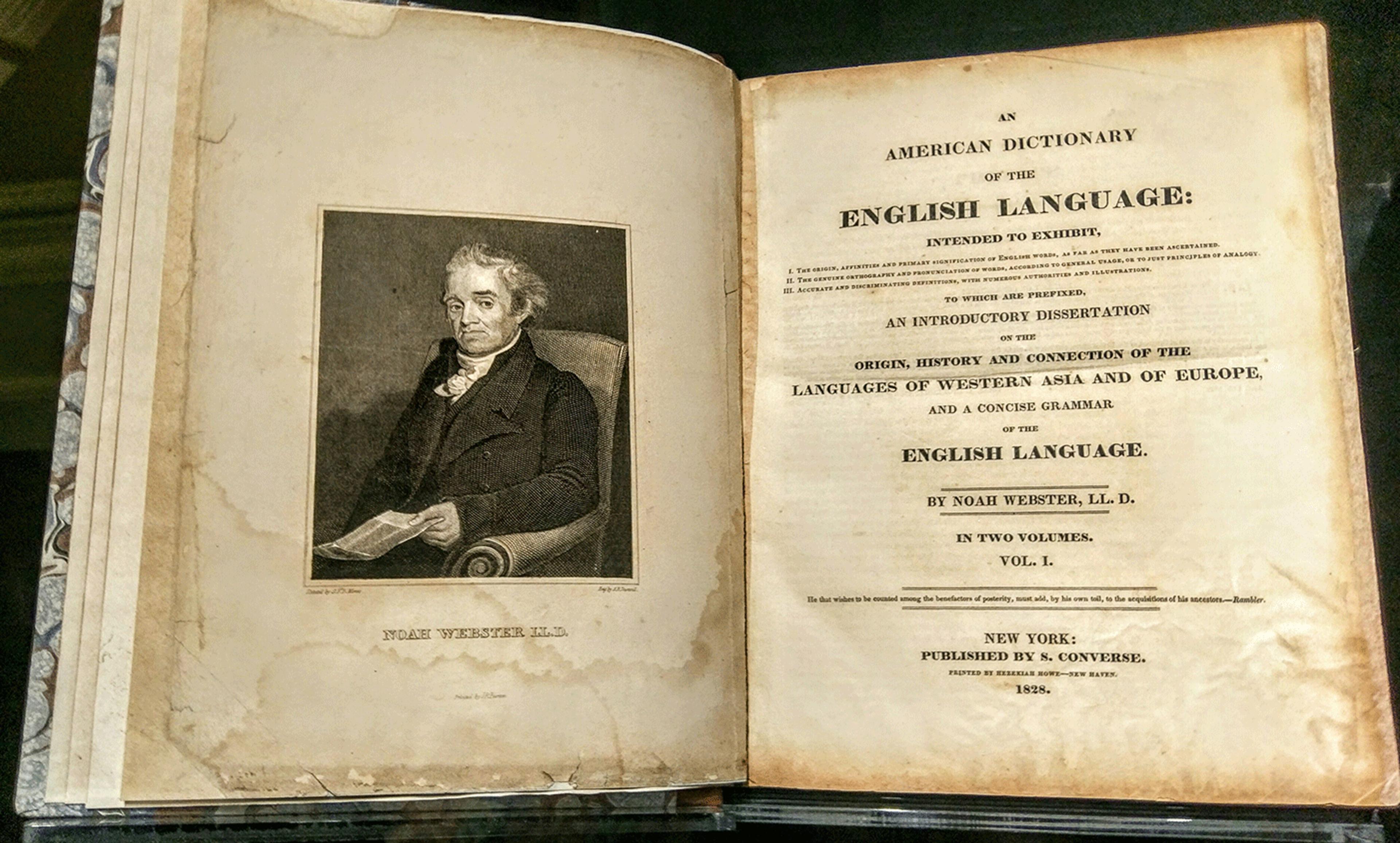

The title page of Noah Webster’s 1828 edition of the American Dictionary of the English Language. Courtesy Wikimedia

In the United States, the name Noah Webster (1758-1843) is synonymous with the word ‘dictionary’. But it is also synonymous with the idea of America, since his first unabridged American Dictionary of the English Language, published in 1828 when Webster was 70, blatantly stirred the young nation’s thirst for cultural independence from Britain.

Webster saw himself as a saviour of the American language who would rescue it from the corrupting influence of British English and prevent it from fragmenting into a multitude of dialects. But as a linguist and lexicographer, he quickly ran into trouble with critics, educators, the literati, legislators and much of the common reading public over the bizarre nature of his proposed language reforms. These spelling reforms – for example, wimmen for ‘women’, greeve for ‘grieve’, meen for ‘mean’ and bred for ‘bread’ – were all intended to simplify spelling by making it read the way that words were pronounced, yet they brought him the pain of ridicule for decades to come.

His definitions were regarded as his strong suit, but even they frequently rambled into essays, and many readers found them overly aligned with New England usage, to the point of distortion. Surfeited with a Christian reading of words, his religious or moral agenda also shaped many of his definitions into mini-sermons or moral lessons rather than serving as clarifications of meaning. A typical example is one of his expositions of purpose: ‘We believe the Supreme Being created intelligent beings for some benevolent and glorious purpose, and if so, how glorious and benevolent must be his purpose in the plan of redemption!’ Overall, his dictionary was prescriptive rather than descriptive, a violation, if you will, of a central tenet of lexicography that holds that dictionaries should record the way language is used, not the way the lexicographer thinks it should be used.

Webster’s etymology, meanwhile, which he spent a decade dreaming up, was deeply flawed because of his ignorance of the exciting discoveries made by leading philologists in Europe about the evolution of Indo-European languages from roots such as Sanskrit. His etymologies conform entirely to the interpretation of words as presented in the Bible. He was convinced that ‘the primitive language of man’ spoken by the ‘descendants of Noah … must have been the original Chaldee’.

Webster fought his battles over language not within philology circles but within the larger context of an emerging American dialect (pejoratively dismissed by the British as provincialisms). He believed that increasing immigration, the multiplication of unique American words, the new meanings attaching to English words and the proliferation of slang – or, as the English saw it, vulgar and undisciplined language – made an American dictionary essential to American life.

New words came from several sources. Native Americans contributed wampum, moccasin, canoe, moose, toboggan and maize; from Mexico came hoosegow, stampede and cafeteria; from French, prairie and dime; meanwhile, cookie and landscape came from the Dutch. Existing words were combined to make new ones, for example rattlesnake, eggplant and bullfrog. Settlers of the West borrowed mesa and canyon from Spanish, and came up with robust words and expressions such as cahoots and kick the bucket. There were also entirely new words: gimmick, fudge, notify, currency, hindsight, graveyard, roundabout. Shakespearean and other Old World words returned: gotten (got), platter (plate), mad (angry). There were new spellings, too, a few of them of Webster’s own invention: some of those were preserved – specter (spectre) and offense (offence) for example – but many more were mocked: wimmen (women), blud (blood), dawter (daughter). Idiomatic ‘tall talk’, as Daniel Boorstin called it in The Americans (1965)– the robust informality and ‘brash vitality’ often attacked by the British as vulgar Americanisms – thrived, especially out West: down-and-out, flat-footed, to affiliate, down-town, scrumptious and true-blue. Not surprisingly, the British worried that, one day, if this mushrooming of Americanisms continued, they would scarcely be able to understand Americans.

That didn’t happen. Because of high mobility and the blending of different cultures and backgrounds in the US, there were far fewer dialects or dramatically different pronunciations than in England, where isolation was more common in spite of the smallness of the country.

The British thought that Samuel Johnson’s great Dictionary of the English Language (1755) would suffice for America as it did for Britain. Many Americans agreed, but many more wanted their own national dictionary to lend them a type of secular authority that was analogous to the spiritual authority of the Bible. But then there was the question of whose American dictionary would provide such an authority – which consideration instigated the ‘American dictionary wars’. Should Webster’s voice prevail, on behalf of the Americanising of English and the writing of dictionaries that would record such usage? Or would Webster’s great rival Joseph Emerson Worcester (1784-1865) with his more traditional, well-informed and solid scholarship triumph? Their conflict became America’s. What emerged in the country was an adversarial culture concerning language in which Americans fought each other in a civil war of words. It was also partly an ideological war, pitting various sectors of society – political, social, educational, religious – against each other over the direction that American English should take.

Webster died before these wars were resolved, feeling that he had failed as a lexicographer (and a visionary), and disheartened by poor sales of his dictionaries. His legacy and eventual iconic standing was secured largely by his editors (chiefly Webster’s son-in-law Chauncey Allen Goodrich) and publishers (Charles and George Merriam) who began to remove most of his work from his dictionary while he was living, and continued the process over the 20 years following his death. The Merriams knew that Worcester was the superior lexicographer, but they recognised that Webster was more marketable because of his patriot credentials, so they dedicated themselves to cleaning up his dictionary and defeating Worcester in the marketplace.

Ultimately, the Merriams were the real winners in the American dictionary wars, having made a fortune from Webster’s name. Had Webster returned to see what had happened to his dictionary, he probably would have thought of himself as one of the big losers. Meanwhile, American English would pursue its own inevitable national development, with little help from him.