Wikimedia

Northeastern Turkey has not received much attention from scholars of Jewish history. It was not an area of dispute nor a region known to host famous schools such as the Jewish academies (yeshiva) in Babylon, where the Talmud was written. There was only fragmented historical records of Jewish settlement in this area.

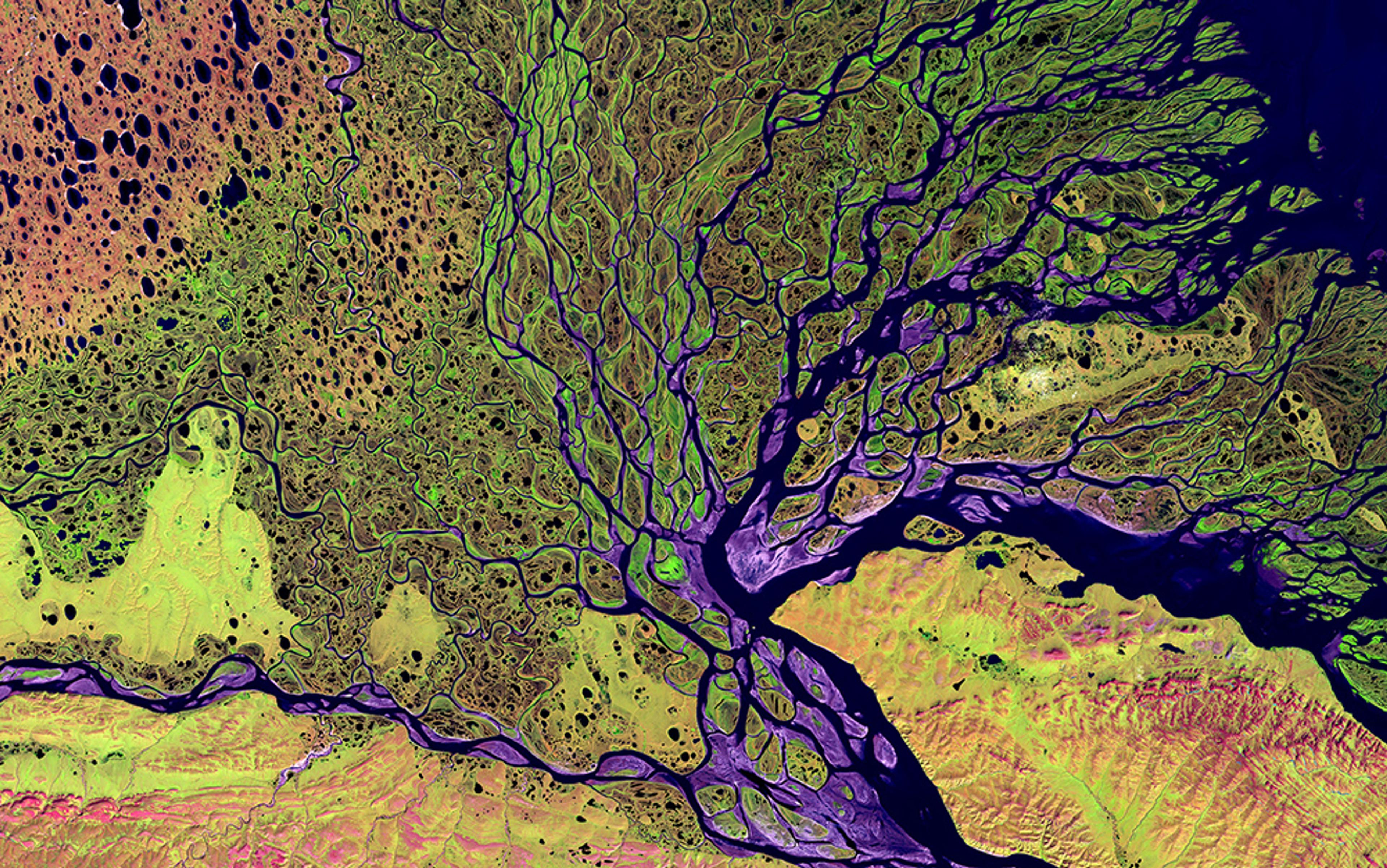

But genetics can now track DNA 1,500 years into the past, with village-level geographical accuracy. This accuracy was made possible with Geographical Population Structure (GPS) technology, which works in a similar way to the satnav geolocation system, and uses DNA instead of satellites to predict the most recent geographical origins of a DNA sample. To study the geographical origins of Yiddish, the native language of Ashkenazic Jews, my lab at the University of Sheffield has applied this GPS technology to the DNA of Ashkenazic Jews. Surprisingly, the results led us to northeastern Turkey, a finding that contradicts the orthodox view that the Ashkenazic Jewry emerged in Germany.

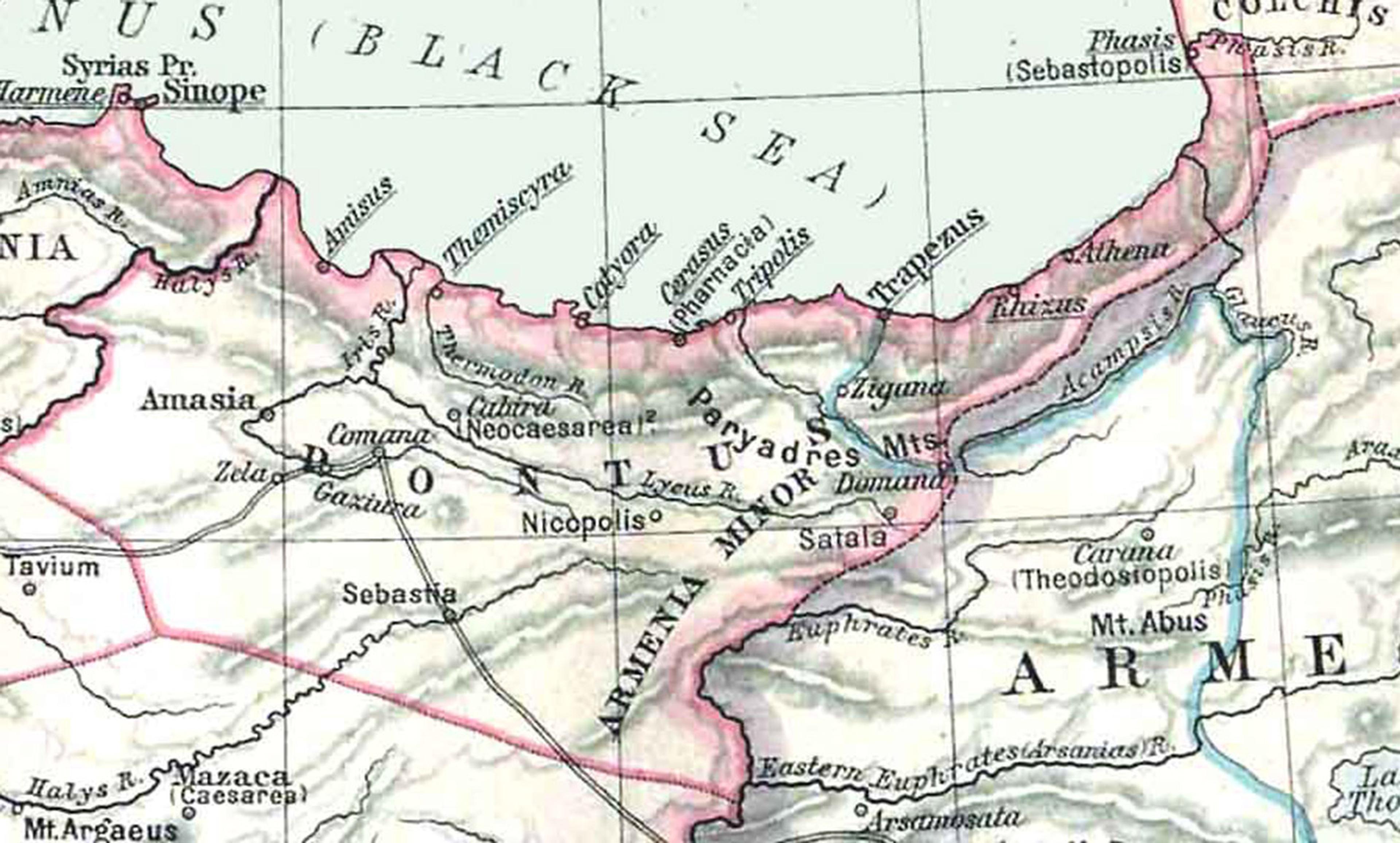

Our continued research revealed that the ancestry of nearly all Ashkenazic Jews could be traced to four ancient villages with remarkable names: Iskenaz (or Eskenaz), Eskenez (or Eskens), Ashanas, and Aschuz (30BCE-640CE). These names might be derived from the word ‘Ashkenaz’, and are unique to northeastern Turkey. There are no other such place names anywhere in the world. However, this area had a rich history.

Until the first century BCE, the region was part of the Greek Kingdom of Pontus. It had been established by Greek settlers in the early first millennium. At that time, Iranian Jews were the largest Jewish community in the world. They held a monopoly on trading on the Silk Roads, and were known to Judaise the people they encountered.

Traces of the Iranian conversion of the Ashkenazic population can be found in the genetic similarity of the two populations, the residues of Iranian in Yiddish, and by certain genetic disorders common to Iranian and Ashkenazic people today, which is of crucial importance to medical research. These findings are of great interest to historians, geneticists, linguists and the large community of genealogists.

But genealogy was not always a popular hobby. It was not until the early civil rights movement of the late 19th century that non-elites began researching their ancestry and celebrating their newly found identities. Before then, genealogy had been something elites used to legitimate political rule.

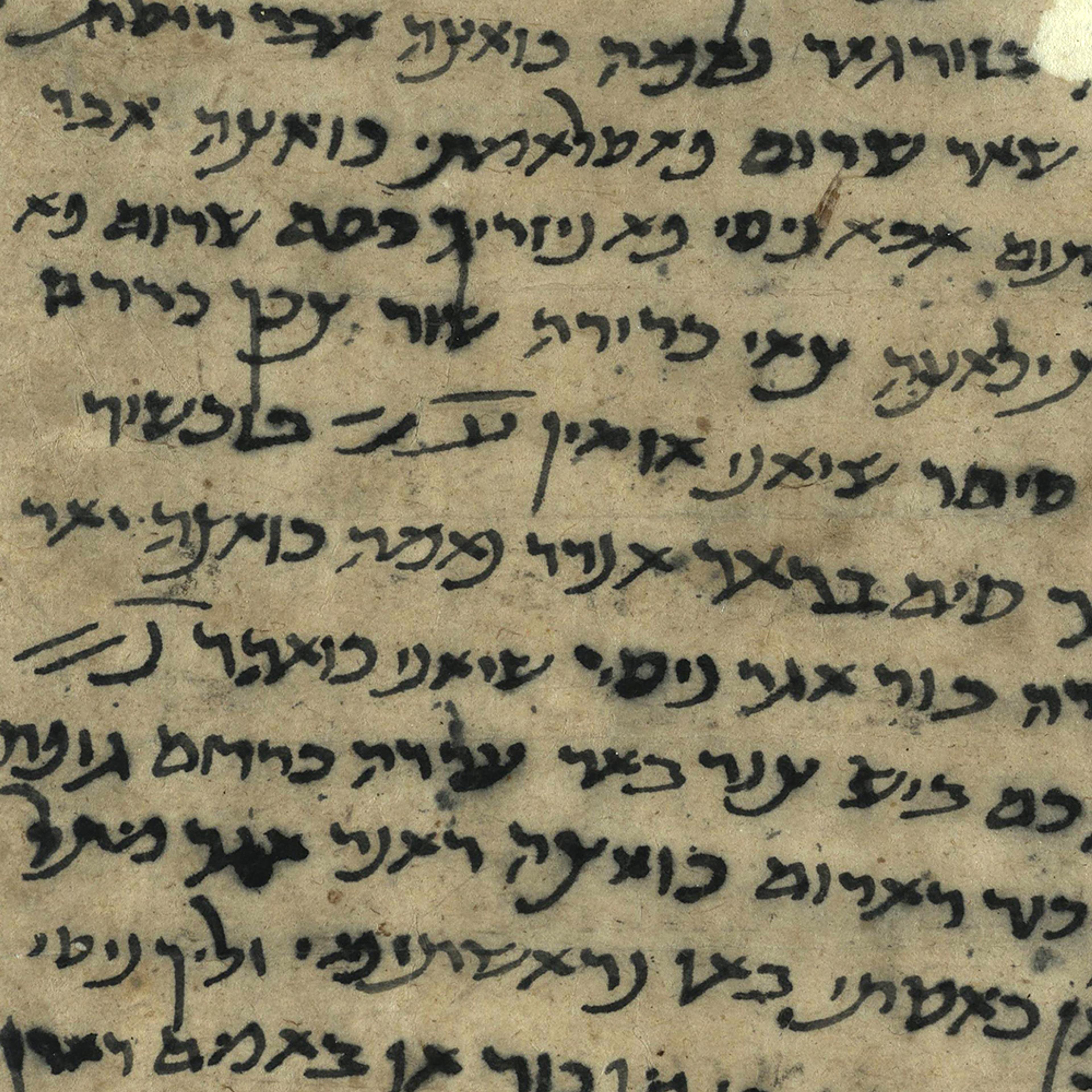

Digital technology has recently improved the accessibility of genealogical records. But even in the best-case scenario, genealogical records could take us back only about 500 years. Now, genetic research allows us to establish findings far beyond five centuries.

Genetic tools for genealogical research initially consisted of classifying individuals into paternal and maternal haplogroups, each prevalent in a different part of the world (eg. western Europe or Oceania). However, these haplogroups allowed for only very imprecise chronological placement or identification within the past 2,000 to 20,000 years. By 2003, new genetic genotyping technology enabled a newly comprehensive – and affordable – analysis. This new technique drew on the remaining 22 chromosomes (called autosomal), which reveal a great deal more information than techniques based only on haplogroups. Analysis based on autosomal characteristics tells us more about the genome, allowing broader and more specific inferences of the past. Comprising of more than 90 per cent of our genomes, autosomal chromosomes enable major advances in genealogical research. Since they are inherited from both parents, they also preserve their genetic signatures, allowing us to learn about our family’s genetic history.

It is important to bear in mind that genealogical research into the past can answer only certain questions. Importantly, it cannot tell the significance for our time of genealogical findings. Interpreting the meaning of millions of mutations is also a different kind of challenge from interpreting the meaning of a 300-year-old diary record of a remote ancestor who had 10 pigs and five roosters. Biogeography aims to provide contextual meaning by tracing both the geographical origin of DNA and the particular time it originated in the population. As scientists’ understanding of genealogical mutations has improved, so too have we been able to develop biogeographical tools to trace the origin of the DNA with more precision.

And so, in 2014, we developed GPS, capable of tracing the geographical origins of individuals with an accuracy, in the best-case scenario, down to village of origin. At present, the technology works best for no more than 1,000 years in the past. Beyond that, the results become more imprecise and speculative.

But can GPS help generate new knowledge? Can it illuminate the history of past cultures and languages? In 2016, we attempted to answer this question by applying GPS to the genomes of nearly 400 Ashkenazic Jews. Half of them came from families who speak solely Yiddish. The language is at least 1,100 years old yet, even after centuries of research, its geographical origins remain uncertain. But since geography and genetics are connected with language (as evidenced by GPS), we surmised that predicting the origin of Yiddish-speaking Ashkenazic Jews would also indicate where Yiddish originated. Linguistic studies had pointed at either Germany or the western Khazarian Empire in modern-day Ukraine as potential points of origins.

Our research, however, led us to conclude that the origin of the Ashkenazic DNA signature derives from the encounter of Iranians Jews, Greeks and other peoples in northeastern Turkey.

This region might hold the answers to the origins of the Ashkenazic culture, customs and rituals, but it was never systematically scrutinised for ancient Jewish remains. We hope that the findings enabled by our GPS technology will stimulate further investigation. Follow-up research can help provide more answers to one of the most mysterious and secretive chapters in history: the ancient origin of the Ashkenazic Jewish community and the Yiddish language.