Florence Ivy/Flickr

‘You step into the little stationery shop – or maybe it’s the corner drug store, the restaurant, the saloon, the roadside inn or the penny arcade. Instantly, the glittering device – its name may be Red Hot, Lineup, Landslide, Brite Spot, Mascot, Three Score or Sporty of Scoop – catches your eye. You walk over to it, gravely study the set-up for a moment, then drop in your nickel and fire away. The lights begin to flash, the sparks begin to fly, the bells and bumpers jingle and whir. You are in the throes of the great American pastime – pinball.’ – Sidney M Shalett, New York Times Magazine (1941)

I grew up playing pinball. I spent many happy hours at my local arcade pushing quarters into the slots of glass-topped mini-worlds, often under the tutelage of my father. He taught me how to pull the plunger just so, how to wait for just the right moment to press the powerful flippers and send the silver ball careening on its way. It was a wholesome, fun way to pass a Saturday afternoon. When I recently told him that pinball had once been banned in much of America, I expected him to be shocked and amused. ‘Oh yes,’ he immediately replied. ‘Your grandfather was totally against playing pinball. He said it was immoral and tied to the Mafia and gambling.’

Though his response initially surprised me, it actually makes sense. My grandfather had come of age in the ‘30s and ‘40s, when many local and state governments waged a war on the newfangled pinball machine. And once the propaganda that something is evil has been absorbed, it can be hard to shake off.

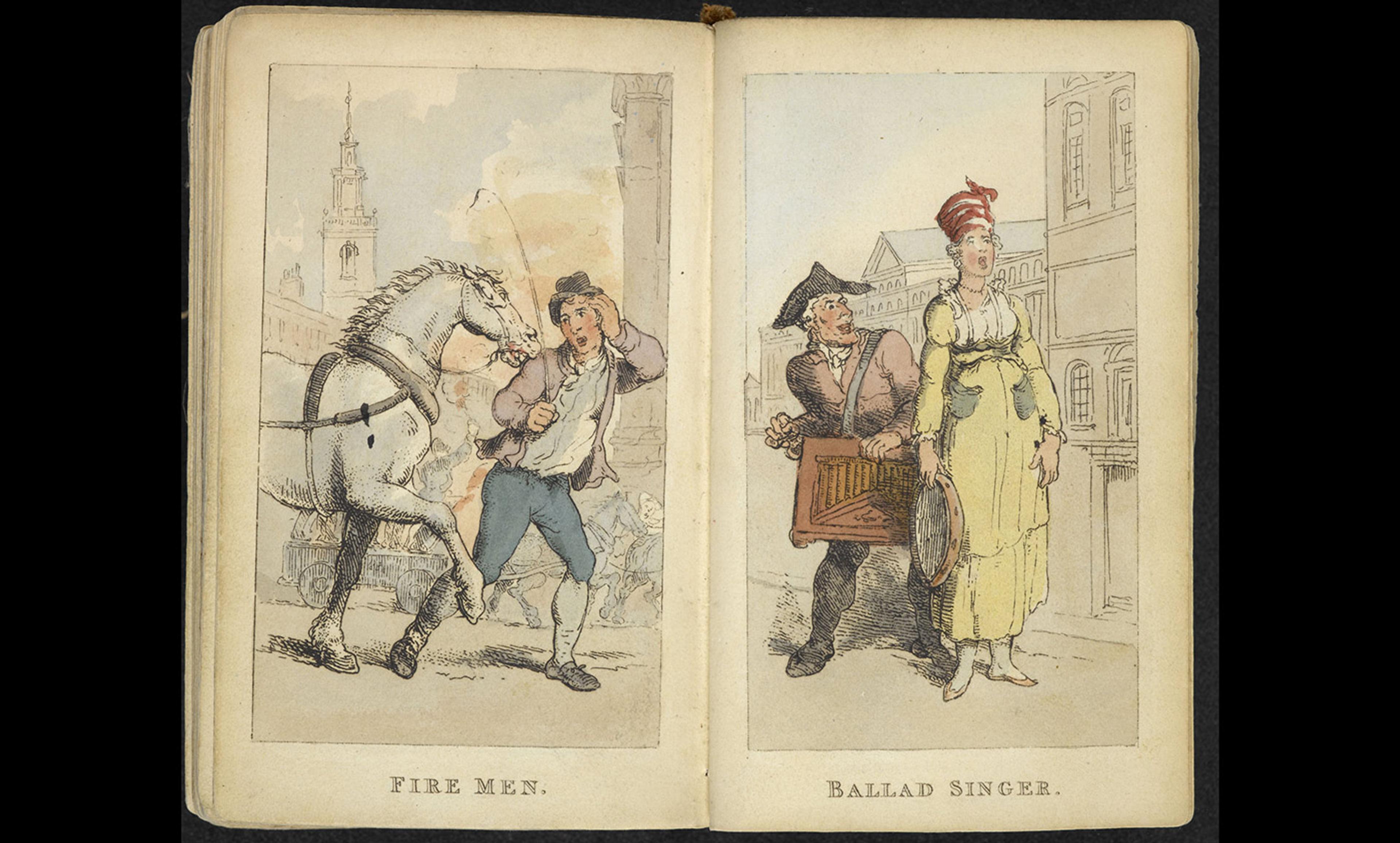

Games like pinball have been played since ancient times. During the decadent reign of Louis XIV, restless courtiers at Versailles became enchanted with a game they called ‘bagatelle’ which means a ‘trifle’ in French. This game was played on a slanted felt board. A wooden cue was used to hit balls into numbered depressions in the board – usually guarded by metal pins. The game arrived in America in the 19th century, and by the turn of the 20th century attempts were being made to commercialise the game. According to Edward Trapunski, author of the invaluable pinball history Special When Lit (1979), the first successful coin operated bagatelle game, Baffle Ball, was produced by the D Gottlieb Company at the end of 1931.

Soon the metal plunger took the place of the wooden cue stick, and lights, bumpers and elaborate artwork appeared on the machines. The game had arrived at the right time – the Depression had just hit America hard, and the one-nickel amusement helped entertain many struggling citizens. It also kept many small businesses afloat, since the operator and location owner usually split the profits 50/50. The game was particularly popular with youngsters in claustrophobic cities like New York, which boasted an estimated 20,000 machines by 1941. That year, one local judge who was confronted with a pinball machine during a case voiced the complaint of many older citizens when he whined: ‘Will you please take this thing away tonight. I can’t get away from these infernal things. They have them wherever I go.’

Although pinball was quickly vilified in many parts of America, the poster child for the vilification was none other than ‘the little flower’ himself: the pugnacious, all-powerful Fiorello H La Guardia, mayor of New York City from 1934 to 1945. La Guardia argued that pinball was a ‘racket dominated by interests heavily tainted with criminality’, which took money from the ‘pockets of school children’. In one rant, he fumed:

The main [pinball] distributors and wholesale manufacturers are slimy crews of tinhorns. Well-dressed and living in luxury on penny thievery…I mean the manufacturers in Illinois and Michigan. They are the chief offenders. They are down in the same gutter level of the tinhorn.

Although to our eyes these allegations seem hysterical, there is some proof to back up La Guardia’s beliefs. After an intense crackdown on slot machines in 1932, there is no doubt that some gamblers turned to pinball to satisfy their wagering itch, which some manufacturers, particularly the Bally Company, facilitated and supported. According to Trapunski, the name ‘pinball’ itself was coined by reporters in Louisville, Kentucky, when they were covering a gambling case centred on the games. And, most damning of all, early pinball games did not have flippers. You simply pulled the plunger and the ball went where it wanted to go.

There is also the fact that with the repeal of prohibition in 1933, some organised crime groups did turn to ‘games of chance’ like pinball to shake down small business owners. Local officials purportedly accepted bribes to license the games. Ninety per cent of pinball machines were manufactured in mob-tainted Chicago. Many machines were owned by Jewish and Italian businessmen, who were unfairly branded as crooks. And, of course, pinball was a game loved by the young. All these things contributed to the public’s negative perception of pinball.

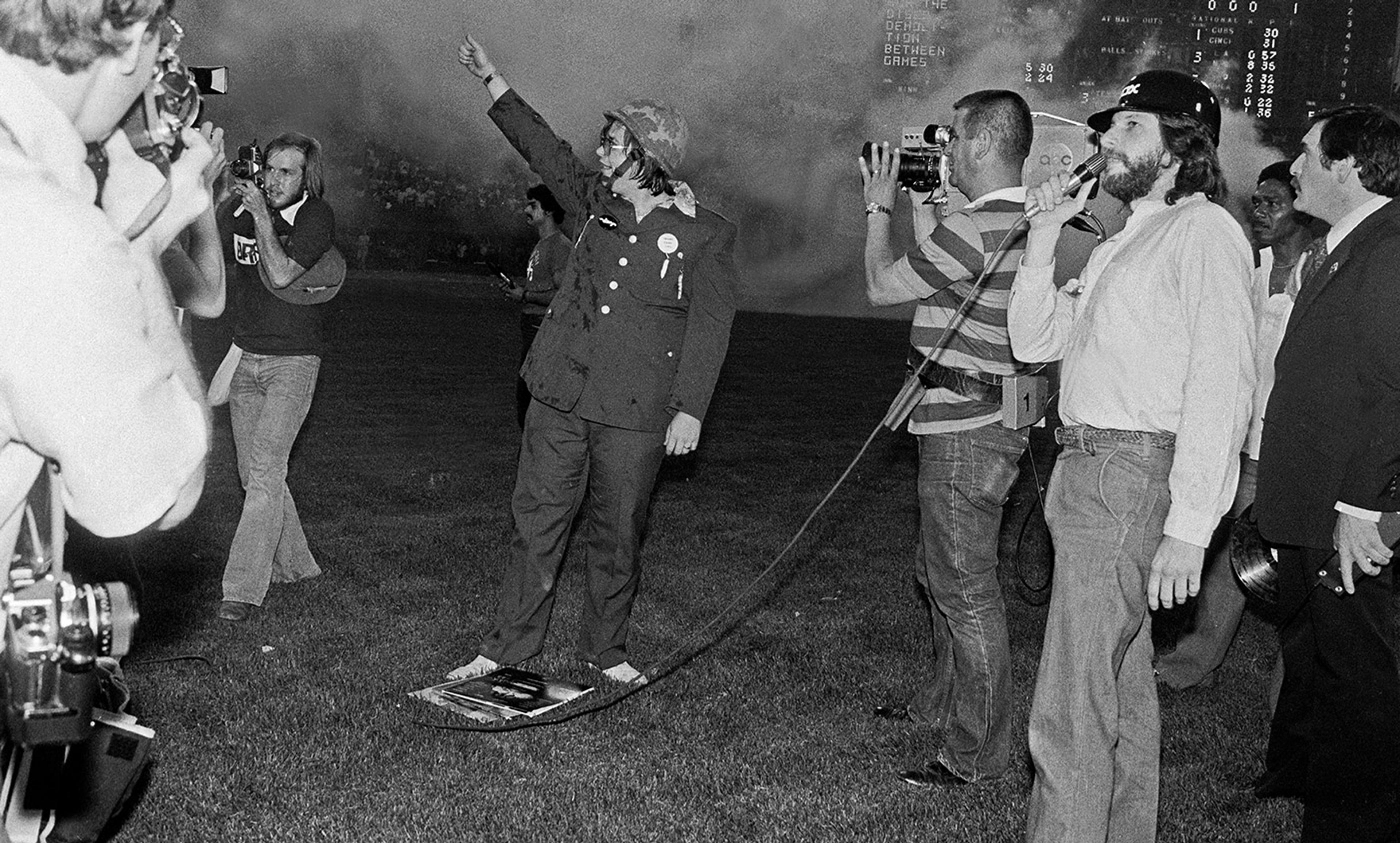

La Guardia and other leaders took these facts and ran with them all the way to the political bank. In 1941, La Guardia and the NYPD set up a much publicised ‘pinball squad’ of eight patrolmen to investigate the so-called pinball ‘racket’. In January 1942, New York Judge Ambrose J Haddock ruled that all pinball machines were gambling devices, and therefore illegal. Before the ruling could be overturned or stayed, La Guardia and the NYPD sprang into action. Within days, it was reported that ‘pinball machines throughout the city clacked and jangled merrily…but only on the backs of policemen ordered to confiscate them’. By October 1942, 4,999 pinball machines in New York City had been destroyed, and over a thousand summonses had been issued. The industry was further decimated that year when the American government ordered all manufacturing in the amusement industry shut down in order to aid the war effort.

The raids were a public relations bonanza for the wily La Guardia. The mayor could point to these raids as proof that he was tough on crime. The confiscated machines were broken down and used to aid the war effort and meet shortages caused by the conflict. In one radio address, the mayor explained that one machine could be turned into 77 brass buttons for NYPD officers. Portions of some machines were sent to educational institutions like Columbia to aid in electronic studies, while other parts were melted down to make bullets and bombs. At one public event, Police Commissioner Valentine of the NYPD, showed La Guardia police clubs which had been fashioned from the legs of the machines. ‘You see how nicely these ring,’ Valentine told the mayor, clanging two clubs together. ‘I’d like to hear them ring on the heads of these tinhorns,’ the mayor replied.

The pinball industry was not down for the count for long. After wartime manufacturing restrictions were lifted in 1945, pinball machines again began to flood into New York City. ‘I could not believe it was so when I read it,’ La Guardia, in the last year of his reign, exclaimed. ‘Commissioner Valentine, keep your eyes open and nab the first one that comes in. Just roll it into the station house and mark it for identification. Do not let them get a start.’

In 1947, the main argument against pinball – that it was undoubtedly a ‘game of chance,’ was negated with the release of the D Gottlieb Company’s ‘Humpty Dumpty’ which included a now standard flipper. However, this didn’t matter to La Guardia’s successor, Mayor William O’Dwyer. While some on the city council fought to license pinball machines, claiming that they were simply harmless amusements, O’Dwyer responded, ‘over my dead body’. So on 1 July 1948, a law declaring pinball illegal in the city of New York officially went into effect. Photos of policemen smashing up confiscated machines filled the local papers, and those in the pinball trade, mostly small business people and veterans, were again dragged into court and fined.

These scenes were replicated all over the US during the 1940s and ’50s, and largely supported by much of the public, who like my grandfather, had been thoroughly convinced of pinball’s moral rottenness. The game was banned in Los Angeles, Atlanta and even Chicago.

Decades after pinball machines had lost any of their purported ties to organised crime or gambling, the bans remained, vestiges of a bygone prejudice. As one New York Times reporter wrote in 1975, ‘with the state in the lottery business, the city taking bets on the horses, pornographic films being advertised in the press and prostitutes plying their trade on busy corners,’ the pinball ban was ludicrously outdated. It was finally lifted on 1 April 1976, but only after a pinball wizard named Roger Sharpe proved to some elderly sceptics on the New York City Council in 1976 that pinball was indeed a game of skill. Other cities slowly lifted their bans as well, though remarkably the city of Oakland, California did not follow suit until 2014.

Moral outrage over flimsy issues can often be a dangerous diversion, falsely soothing our prejudices and fears. In times of change and uncertainty, politicians and moral leaders often vilify products that give some people pleasure. Railing against video games or vibrators or vending machines is a way to concentrate anger, to make people feel their governments can actually get something done, that the world is not as out of their control as appears to be.