Ik T /Flickr

Easter Island, also known as Rapa Nui, is an island in the Pacific famous for the massive humanoid statues peppered along its coasts. These moai are commonly called stone heads, but actually most possess bodies, and the largest constructed stands at over 30 feet and weighs 82 tons. Ever since these monoliths were encountered by European explorers in the 18th century, the history of the island has been a topic of fascination and debate. Most captivating is the mystery of how almost 900 moai were carved and transported, mostly between 1250 CE and 1500 CE, only to be toppled and abandoned by the 18th century.

The history remains contentious and its scholarship is currently hosting a fierce debate between two rival camps. The first account, popularised by Jared Diamond in his bestselling book Collapse (2005), presents the island’s history as a cautionary tale of the destructive potential of humans to overexploit natural resources. A contradictory account has been advocated over the past decade by a group of scholars, led by the anthropologists Carl Lipo and Terry Hunt, who contend that the ‘collapse’ Diamond describes is largely a European myth. Instead, continuity is the hallmark of settlement on Rapa Nui.

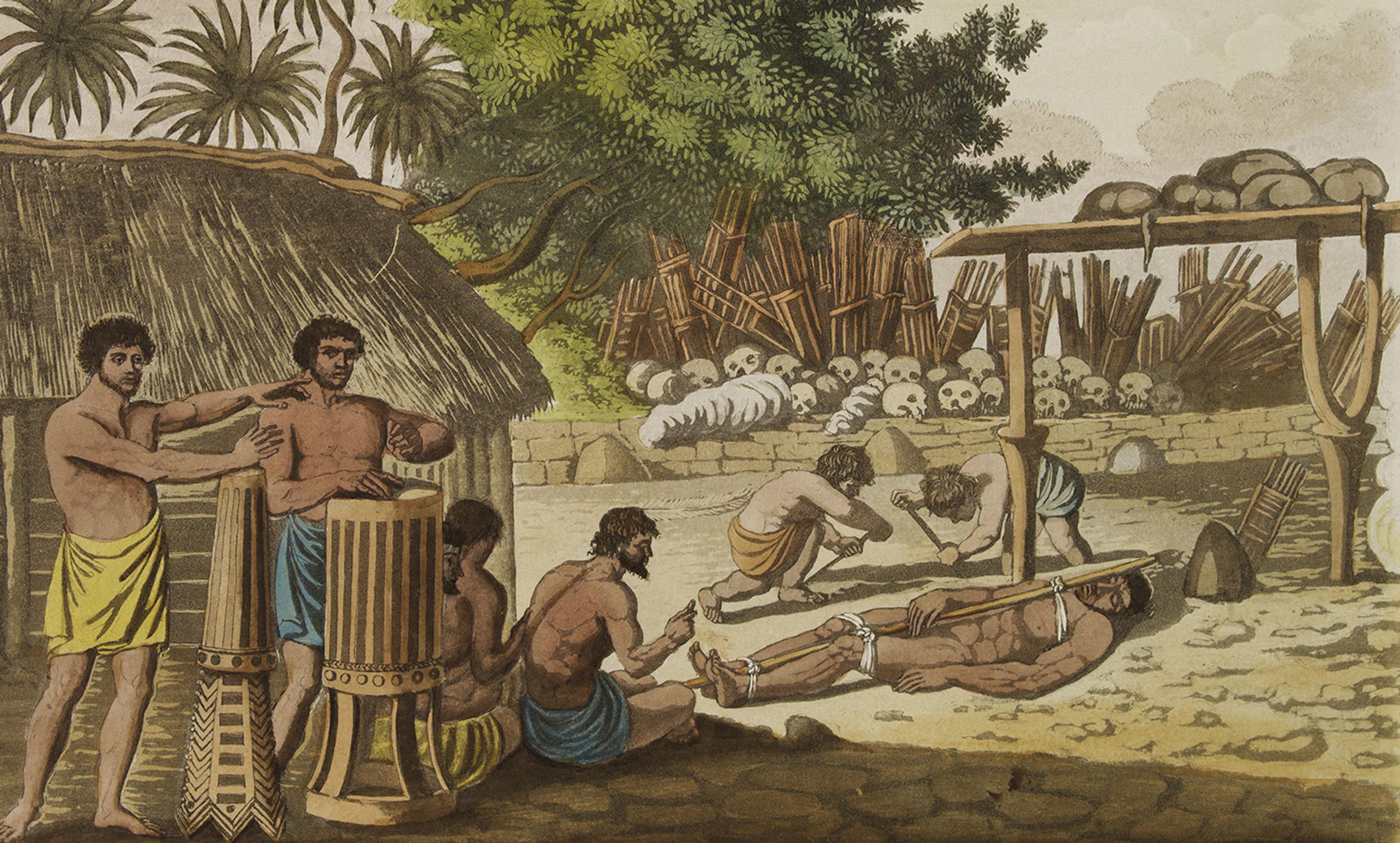

Let’s start with the Collapse narrative, a simplified version of which goes as follows: Easter Island was once a lush forested environment that housed a thriving Polynesian civilisation. However, overpopulation and destructive agricultural practices eventually depleted its natural resources, which in turn resulted in destructive tribal conflicts. Starvation, mass warfare and even cannibalism led to a population crash, from an estimated high of approximately 15,000 to just 2,000-3,000 by the time Europeans arrived in the 18th century.

The moai have a part in this story, too: the pressure on resources is thought to have been exacerbated by the need for trees, which served as a means of transporting the massive icons that signalled a chief’s status and power. Even this had to end, however, and moai construction was ultimately abandoned, with many half-finished monoliths left standing in a quarry. European settlers found the existing moai all toppled, victims of wartime defiance.

This story has spread well, but it is not without its critics. A significant group of scholars favour an alternative interpretation, arguing that Polynesian rats (perhaps as many as 3 million), and not humans, were responsible for much of the deforestation. In this telling, the island’s population was never much higher than 3,000, and the construction of moai was not really that resource-intensive. This latter point forms the core argument of Lipo and Hunt’s book The Statues That Walked (2011), which proposes that the moai did not require many trees to transport, as they could be ‘walked’ upright into place by small groups rocking them from side to side by rhythmically pulling them with ropes.

This year, another new study led by Lipo and Hunt analysed obsidian artefacts known as mata’a which are found on Rapa Nui, and claimed to offer more evidence in support of their position. Mata’a are plentiful across the island, and were previously believed to be spear points. They were therefore seen as archaeological evidence that supported oral traditions of mass warfare on the island. But the new study called this interpretation into question by demonstrating that the mata’a came in many shapes, most of which would have been poor for stabbing and piercing. Instead, the authors suggest that mata’a were more likely used as tools in agricultural cultivation, or as part of domestic and ritual practices.

This study presented a compelling case and made a valuable contribution to the research literature examining the island’s history. However, the way such scientific studies are packaged by university PR departments, promoted by academics and then presented to the public is a problem. Following the study, there was a brief glut of articles with headlines such as ‘New Evidence: Easter Island Civilisation Was Not Destroyed by War’ and ‘Easter Island: Prehistoric Warfare Did Not Bring About Collapse of Rapa Nui Population’. Most of the articles summarising the study presented it as decisively overturning a false consensus based on Diamond’s misleading portrayal, and quotes from the study’s authors seemed to reinforce this view.

It is understandable why this is an appealing angle: Diamond is a controversial figure, especially among anthropologists (a 2013 paper was titled ‘F**k Jared Diamond’), and he has repeatedly been accused of misrepresenting facts to fit his grand narratives. Additionally, the narrative that Lipo and Hunt promote sits better with modern sensibilities as it suggests that the Rapa Nui people suffered no real collapse prior to their well-documented mistreatment by Europeans. Conversely, Diamond’s narrative can be (uncharitably) presented as a case of academic elites blaming powerless victims, largely due to the unreliable reports of racist European sailors, in order to generate a modern ecological morality tale for a modern Western audience.

The appeal of the alternative account to current political palates is precisely why caution is warranted: a narrative’s popular appeal is a poor indicator of its truth. This is not to say that we should reject Lipo and Hunt’s study or the continuity hypothesis more broadly, but rather we should be careful not to overinterpret studies lest we fall into a classic case of wishful thinking. Single studies very rarely establish a new consensus in science, and this case is no exception. Indeed, in the paper’s actual conclusion, despite restating their alternative thesis, the authors commendably and candidly state: ‘This conclusion does not imply that prehistoric islanders did not experience violence, only that mata’a do not appear to be related to systemic warfare.’

Rather than the final nail in the coffin of some discredited pet theory of Diamond’s, Lipo and Hunt’s study actually contributes a new piece of evidence to a lively and ongoing debate among a broad range of scholars. What’s more, from surveying the literature, my assessment is that most scholars in the field (broadly) agree with Diamond’s thesis about a human-caused ecological and population decline, more than they agree with Lipo and Hunt’s alternative. The crucial point is that such debates continue, and can almost never be settled by a single study or analyses of a single type of artefact. Writers, readers, researchers and scientists must recognise that most questions worth asking demand complex answers that cannot be provided by any single study, regardless of whether we prefer the narrative it implies.