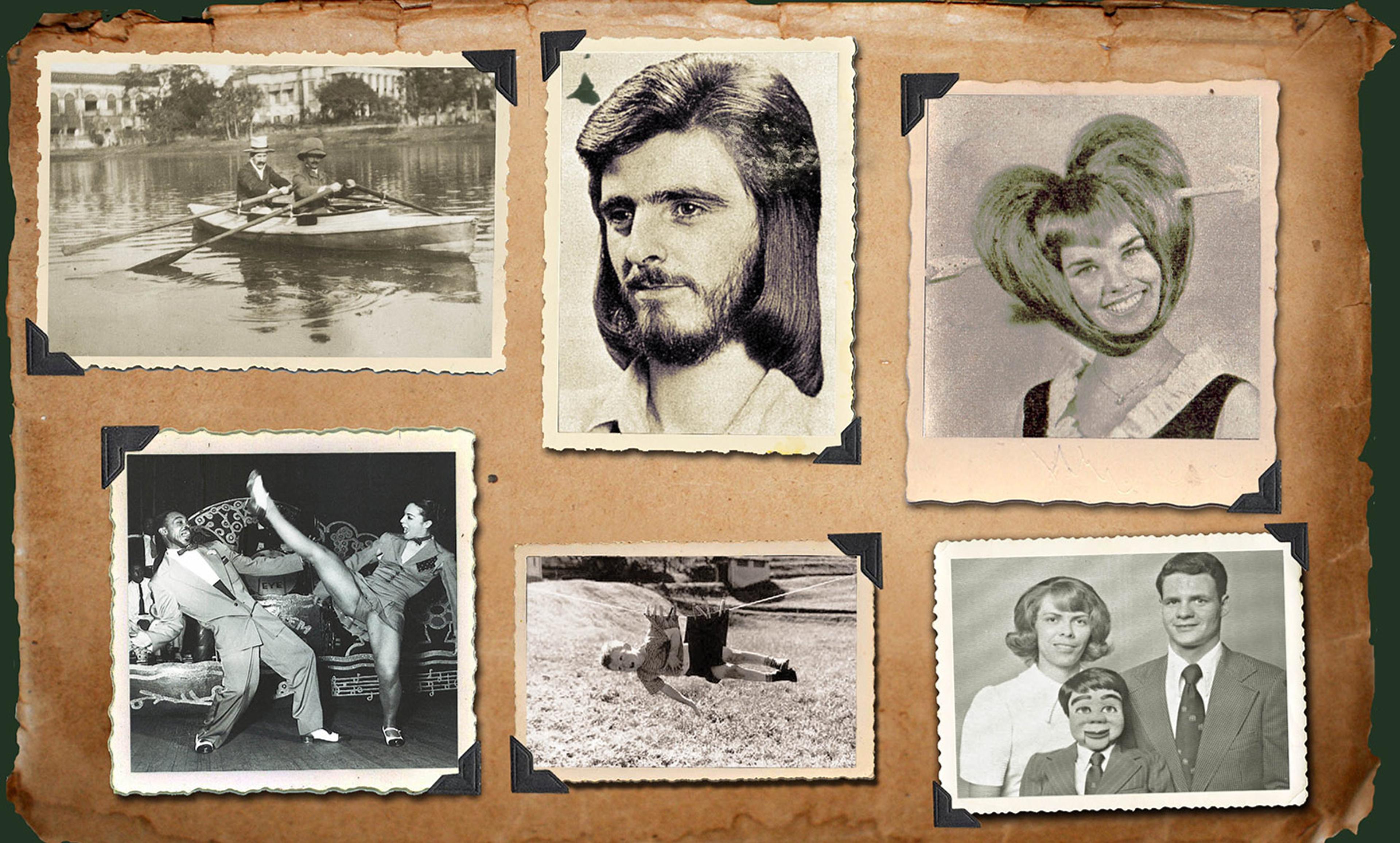

Fans of the rapper Cardi B. Photo by Jessica Rinaldi/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

Why do so many people care so much about celebrities? Just as each generation believes it invented sex, so each thinks it created celebrity. Ask someone born in the 21st century what defines celebrity culture, and they will likely single out the digital media that allow anyone with a cell phone to ‘like’, retweet and comment on a Kim Kardashian post in seconds.

The mid-century cultural critics Theodor Adorno and Daniel Boorstin had a more paranoid view: they believed that the media imposed stars on a mindless public. Then in the 1980s and ’90s, the scholars Jackie Stacey and Henry Jenkins saw the public as in charge, making or breaking stars. In prosperous times, celebrity biographies tend to attribute stardom to talent, luck and hard work. In precarious times, we hear more about icons who self-destruct.

All these views assign power to one and only one element in the equation: the media, the public or the stars. All of them are wrong – because all of them are right. No single group has the power to make or break a star. Three equally powerful groups collude and compete to define celebrities: media producers, members of the public and celebrities themselves. None has decisive power, and none is powerless.

The three-way effort to create, define and undo celebrities is tireless. To become famous, the American rapper Cardi B had to do more than record catchy tunes. She had to promote them effectively to people who liked them. She had to be outrageous and self-revealing enough to garner a huge following on Instagram. She had to collaborate with a celebrity band, Maroon 5, and feud with the already established star rapper Nicki Minaj. (Don’t know who these people are? Many 12-year old girls will be happy to enlighten you.)

In January 2019, Cardi B won an online battle with Donald Trump when she posted an Instagram video calling his government shutdown ‘crazy’. The Twitter-mad president signalled his defeat with an uncharacteristic response: silence. A month later, Instagram trolls attacked Cardi B for not deserving her Grammy. She left the platform, only to return two days later. The story continues.

Social media amplifies and speeds up interactions between audiences, media and stars, but YouTube and Twitter did not invent modern celebrity culture. That happened more than 150 years ago, thanks to the popular press, commercial photography, railways and steamships, and national postal systems.

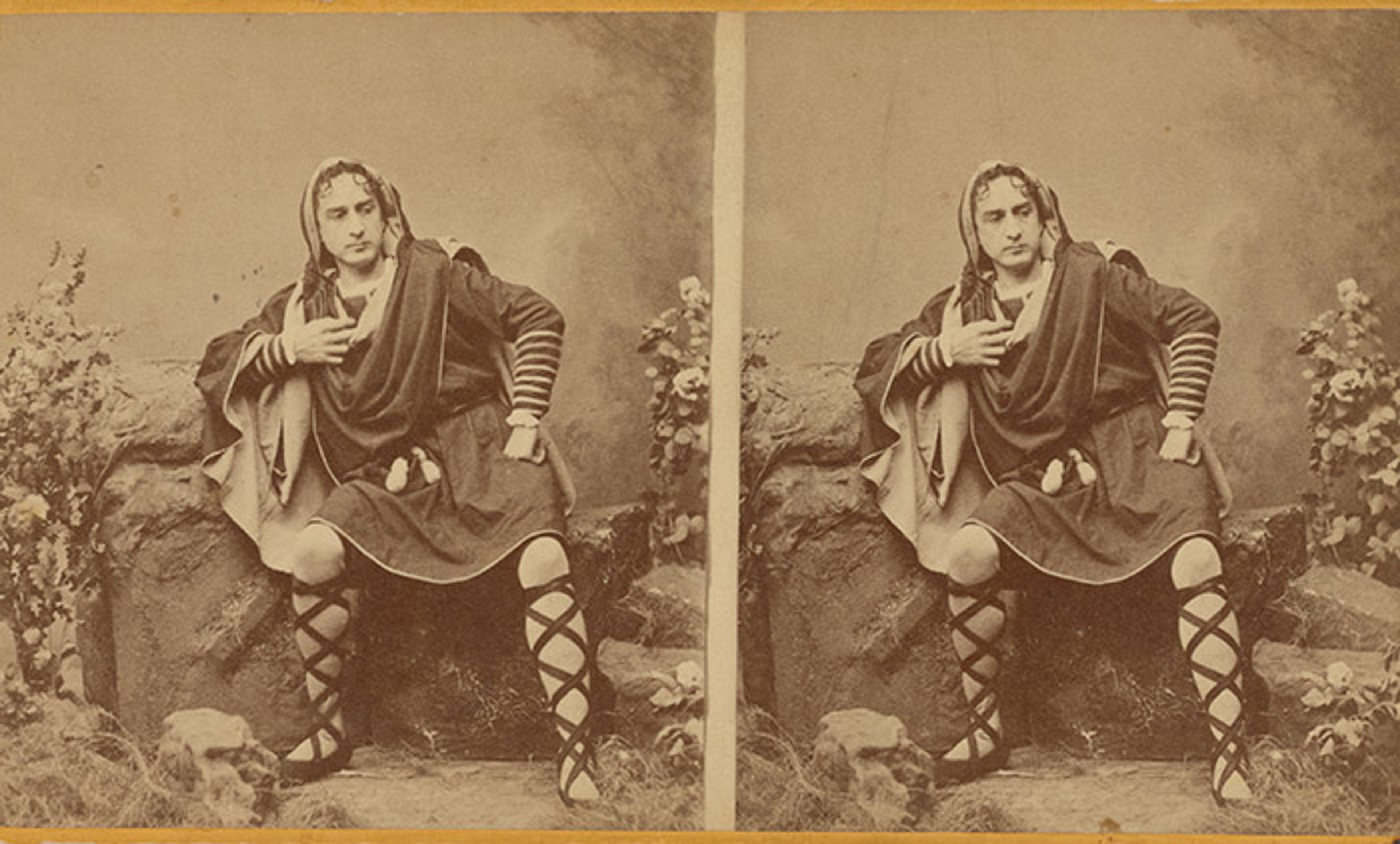

Consider Edwin Booth (1833-93), one of the most famous American actors of the 19th century. Remembered today, if at all, as a brother of the man who assassinated president Abraham Lincoln, Booth became known in his time for playing Hamlet, Richard III and Brutus in Julius Caesar. His acting yielded enough money for him to buy several theatres and a Gramercy Park mansion in New York City that he turned into an all-male club, the Players, where actors could rub shoulders with elites. He lived on the building’s top floor, surrounded by books, theatrical memorabilia and the hundreds of letters he received between the 1860s and ’90s and chose to save.

Edwin Booth. Courtesy NYPL Digital Collections.

Booth’s fanmail attests to the many links connecting 19th-century audiences, media and stars. Thanks to steamships, he had performed in Europe and received letters from England and Germany. Thanks to railways, his US audiences included major cities and smaller locales from Akron to Zanesville.

Some of the letters that Booth preserved were ‘mash notes’ soliciting assignations. Others begged for money, jobs or free acting lessons. Some plied him with quack medical remedies or tried to convert him. Dozens sent the actor long poems combining all of the above.

Many letters lavished Booth with praise but quite a few offered unsparing criticism worthy of any Twitter troll. One correspondent in 1866 advised Booth how to be a better Richard III. ‘Your appearance was not sufficiently stern and sombre,’ the writer complained. ‘You might … have a larger hump on the back & a more infirm gait as you move on the stage.’ Other critiques were less polite. ‘Shakespear No 2’ offered pungent advice in a scrawl that grew larger with each line: ‘Mr Booth Your Hamlet is overdone. Your constant contortions render your part monotonous. Some parts are well done but in others where you should act like a rational man you act more like a maniac.’

One correspondent ranked Booth’s critics. A journalist who had reviewed Booth’s Charleston appearances sent clippings for the actor’s perusal. A woman who requested an edition of Booth’s most frequently performed plays used a colour code to distinguish the six different occasions she had seen him as Hamlet.

The French opera singer Pauline Viardot received and kept a similar set of letters, as did the American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. To be sure, 19th-century print publics were less visible to one another than digital publics are today. But the continuities between celebrity cultures past and present are real, and offer a telling clue to what really intrigues people about celebrity culture.

All of us, even those who ignore celebrities, are part of a story whose outcome we can influence but never fully predict. Celebrities are neither pawns nor gods. Every time Cardi B releases a new song, poses for a magazine cover or posts on social media, she can gain or lose status. Members of the public are neither passive consumers nor omnipotent creators. They argue among themselves, and each individual’s decision to engage or ignore celebrities helps to make or break stars. Journalists use celebrity coverage to get the public’s attention. Some criticise celebrities; others cater to them.

The resulting pandemonium is celebrity culture – a drama that many help to script but that no-one fully controls. If we knew for certain how the story ended, we might lose interest. If we had no role to play in the outcome, we might be less intrigued. The moral of this tale: celebrity culture is neither all good nor all bad. But if you don’t like celebrity culture, don’t blame the internet. Blame everyone.