King William I or William the Bastard. Courtesy Wikipedia

Today, ‘bastard’ is used as an insult, or to describe children born to non-marital unions. Being born to unmarried parents is largely free of the kind of stigma and legal incapacities once attached to it in Western cultures, but it still has echoes of shame and sin. The disparagement of children born outside of marriage is often presumed to be a legacy of medieval Christian Europe, with its emphasis on compliance with Catholic marriage law.

Yet prior to the 13th century, legitimate marriage or its absence was not the key factor in determining quality of birth. Instead, what mattered was the social status of the parents – of the mother as well as of the father. Being born to the right parents, regardless of whether they were married according to the strictures of the Church, made a child seem more worthy of inheriting parents’ lands, properties and titles.

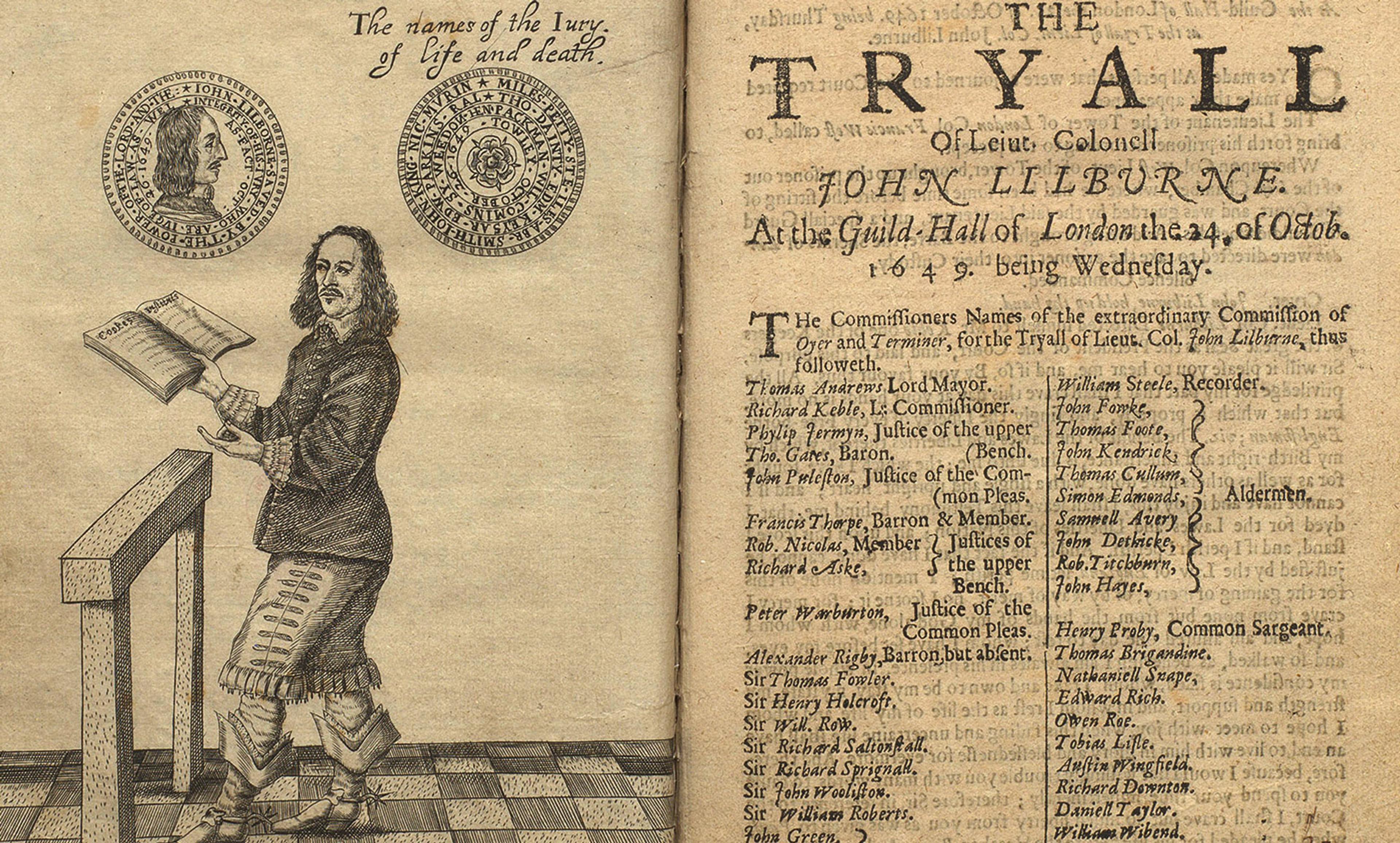

Consider, for example, the case of William the Bastard, more commonly known as William the Conqueror. Born to Robert, Duke of Normandy and Herleva, a woman clearly not his wife, William was nevertheless recognised by his father as his heir. Despite his youth and questionable birth, William managed to conquer and rule first Normandy and then England, and to pass his kingdom and titles on to his children.

Why then was William called ‘the Bastard’? Writing about William in the 12th century, the chronicler Orderic Vitalis called him ‘nothus’, an Ancient Greek term used to indicate birth to anything other than two Athenian citizens. What might Orderic have meant by this? The only elaboration he offered suggests a concern not with William’s mother’s marital status but rather with his maternal lineage. During William’s siege of Alençon in the 1050s, as Orderic wrote, the people gathered on the battlements taunted William not because his father hadn’t married his mother, but over his mother Herleva’s paternity, as the daughter of either a tanner or an undertaker. In other words, they objected not to his birth out of wedlock, but to his mother’s poor lineage. That sense of what made a birth illegitimate, what made a child a ‘bastard’, matches the definition of nothus often found in early medieval sources. As one late-11th-century chronicler declared, the French called William ‘bastard’ because of his mixed parentage: he bore both noble and ignoble blood, ‘obliquo sanguine’.

William’s social advancement, despite his dubious birth, is not unique. Kings before and after him, and even queens, successfully inherited and reigned despite allegations of illegitimacy. There are many cases in which the children of illegal marriages, including even the children of monks and nuns, inherited noble and royal title throughout the 12th century. Children born to a high-status couple could inherit from those parents, even if their union violated contemporary prohibitions on marrying close kin, marrying those already married to other living spouses, or marrying those sworn to celibacy. As such, the ideal of legitimate kingship as defined by legitimate birth, and legitimate birth as determined by a legitimate marriage between the parents, took hold only slowly and inconsistently in medieval Europe. It’s not until the late 12th century that evidence for the exclusion of children from succession on the grounds of illegitimate birth first appears. ‘Bastard’, as we now understand it, began to emerge here.

Importantly, this shift in the meaning and implications of illegitimacy did not arise as an imposition of Church doctrine. Instead, ordinary litigants began exploiting bits of Church doctrine to suit their own ends. Perhaps the earliest signs of this can be found in the annals of English legal history, with the Anstey case of the 1160s. This might have been the first time an individual was barred from inheriting because her parents had married illegally. And it happened not because the Church intervened, but because one clever plaintiff figured out how to exploit some scraps of theological doctrine. After that time, more and more plaintiffs began to do the same.

For example, towards the end of the 12th century, a regent countess of Champagne rushed to make use of an allegation of illegitimate birth against her nieces, in an effort to secure her son’s succession. Daughters could inherit in this region, and so these sisters did have a claim to the county once ruled by their late father. But the regent countess denounced the sisters as the product of an illegal marriage and therefore not legitimate heirs of their father. The strategy worked in that both daughters did eventually renounce their claims to the county, but not without first obtaining a great deal of money, enough to make them both extremely wealthy. As this suggests, the papacy had a far more passive role than is often imagined.

As bastardy began to acquire its modern meaning, in the early 13th century, it remained the case that the papacy focused on the regulation of illicit unions rather than the exclusion from succession or inheritance of those born to illicit unions. Hatred of illicit sex did trump dynastic politics on occasion. Hatred of the children born to such unions did not. There is very little evidence to suggest that an interest in keeping illegitimate children from inheriting noble or royal title outweighed political or practical considerations in the same way that the policing of illegal marriages sometimes did.

Understanding the changing meanings of bastardy helps us to arrive at a clearer picture of the workings and priorities of medieval society before the 13th century. Society then did not operate subject to rigid Christian canon law rules. Instead, it measured the value of its leaders based on their claims to celebrated ancestry, and the power attached to that kind of legitimacy. To be sure, marrying legitimately certainly received a good deal of lip service throughout the Middle Ages. Nevertheless, in this pre-13th-century world, the most intense attention was paid not to the formation of legitimate marriages, but to the lineage and respectability of mothers. Only beginning in the second half of the 12th century did birth outside of lawful marriage begin to render a child illegitimate, a ‘bastard’, and as such potentially ineligible to inherit noble or royal title.

Royal Bastards: The Birth of Illegitimacy, 800-1230 (2017) by Sara McDougall is out now through Oxford University Press.