Wikimedia

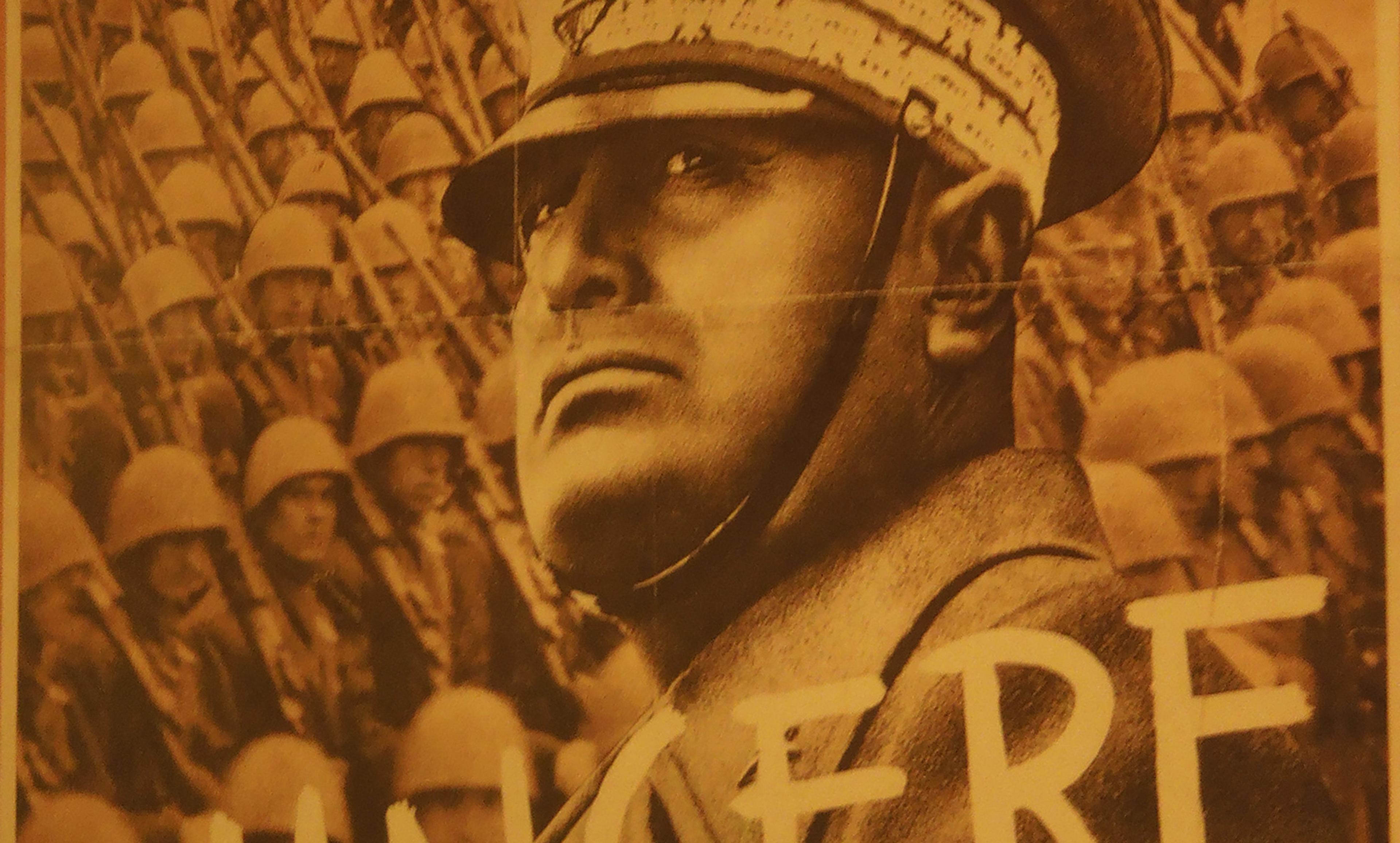

Politicians spend a lot of time trying to portray the leader they oppose as weak. They believe this resonates with a broader public. It’s not only in authoritarian regimes but in democracies, too, that the notion prevails that we need a strong leader. What is usually meant by that is a leader who concentrates a great deal of power in his (or her) hands, dominates public policy, calls the shots in the political party, and makes all the big decisions in government.

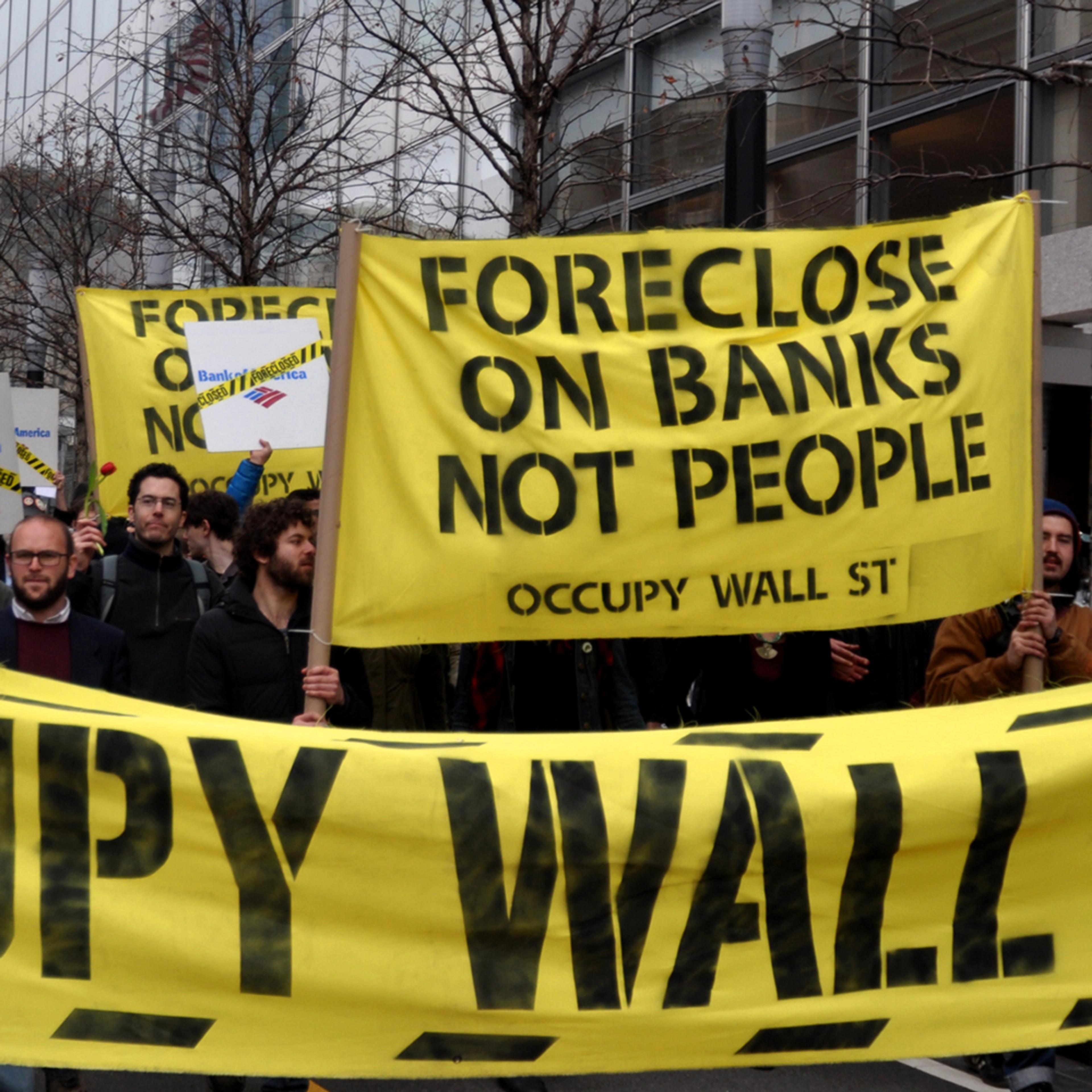

It is a recurring theme of Republicans in the United States that President Barack Obama is a weak leader. In Obama’s case, this is often linked to his failure to deploy US military force in distant trouble spots, even though the calamitous US experience from Vietnam to Iraq hardly suggests his caution is misplaced. The appeal of someone who very consciously projects an image of the strong leader is apparent in the support for the Republican frontrunner Donald Trump. The fact that his policies are a hodge-podge of wildly unrealistic aspirations – such as building a wall to keep Mexicans out of the US, and getting Mexico to pay for it – counts for less than Trump’s ability to persuade disillusioned conservative voters that his strong personality and mobilisation of their anger will somehow, in the words of his campaign, ‘Make America Great Again!’

Yet, whether we are talking about authoritarian regimes or democracies, the idea that the most admirable and successful leader is one who maximises his or her individual power is deeply suspect. In the case of totalitarian and authoritarian regimes, it is especially clear that a more collective leadership is a lesser evil than personal dictatorship. The Soviet Union, prior to the liberalisation and pluralisation of the system during Mikhail Gorbachev’s perestroika, was never less than highly authoritarian. But the USSR in the 1920s and in the period after Stalin’s death in 1953 was a less murderous place than it was during the years of Stalin’s personal dictatorship, which became absolute in the early 1930s. Similarly, China in the first half of the 1950s or in the years since Mao Zedong’s death in 1976 was and remains authoritarian, but the tens of millions who died in the Great Leap Forward and the hundreds of thousands who were killed in the Cultural Revolution were victims of Mao’s personal obsessions and of his power at its most untrammelled.

Overweening leaders within a well-established democratic system can, of course, do less harm than a Stalin or a Mao. Yet why should we heed calls to strengthen the hand of the prime minister and of 10 Downing Street rather than to strengthen collective leadership within the Cabinet and the political party? The mass media are constantly urging prime ministers and party leaders to do this, that and the other, bolstering the odd assumption that the leader is entitled to have the last word on everything.

It is puzzling why the idea persists that the more power is placed in a prime minister’s or president’s hands in a democracy, the better. It is high time to rebut the idea that the leader we should most look up to is one of unshakeable convictions, able utterly to dominate the political party, the Cabinet and the policy process. One-person domination is undesirable in principle in a democracy and it is fortunate that it is only rarely achieved in practice, whatever the leader’s pretensions.

Margaret Thatcher and Tony Blair – in contrast with the more collective post-war British governments headed by Clement Attlee, Winston Churchill, Harold Macmillan, Harold Wilson and James Callaghan – sought to dominate the policy process. Their attempts to do so came unstuck in different ways.

A major contributory factor in Thatcher’s downfall was her overruling of the Chancellor of the Exchequer Nigel Lawson’s objections to the poll tax. To her own ultimate cost, she persuaded a majority of the Cabinet to endorse this extremely unpopular tax. Blair, in contrast, failed in his efforts to take the United Kingdom into the euro. He announced in the year 2000: ‘I will decide the issue of monetary union.’ Blair’s former trade and industry secretary Alistair Darling noted that Blair involved the Cabinet in the policy process more than was his custom in order to achieve that goal. In this case, however, the Chancellor of the Exchequer Gordon Brown prevailed. Brown, who was opposed to the UK entering into the common currency, easily outwitted Blair.

Politicians who like to think of themselves as strong leaders, or who are anxious to be perceived as strong, might be especially tempted by foreign adventures. The two most counterproductive British foreign policy decisions since the Second World War were the military intervention in Egypt in 1956, when Britain colluded with France and Israel, and the invasion of Iraq in 2003, with the UK as the junior partner of George W Bush’s US. In both cases – with Anthony Eden in charge in the first, and Blair in the second – the prime minister was the dominant player in committing UK troops to these wars of choice. In each case, they were less than fully frank with their Cabinet colleagues and paid scant attention to those in the Foreign Office and outside government who knew most about the Middle East.

Prime ministers and party leaders – unless they are as well grounded as a Stanley Baldwin or an Attlee – acquire an unrealistic belief in the exceptional quality of their judgment and corresponding right to pull rank and determine policy, sustained as these convictions are by their entourage and the ambitions of some of those around them. It is not altogether surprising that leaders should fall prey to arrogance and to seeing themselves as being above the party that elevated them to its leadership. What is more astonishing is that so many of the rest of us should undervalue collegial and collective decision-making. Party leaders and prime ministers were not chosen because they were deemed to have a monopoly of wisdom. It is time we stopped worshipping the false god of the strong individual leader.