At the Whitney Museum’s Jeff Koons retrospective in 2014. Photo by Robert Nickelsberg/Getty

For Americans who love art by the likes of Hans Holbein, Édouard Manet, Georges Braque and Paul Klee, dark times lie ahead. Each one is a brilliant artist, but none is a household name like Claude Monet or Pablo Picasso. After years of declining public arts education, only the most high-profile artists are recognised by the general public, capable of luring people to see their art in museums. And that spells trouble for artists of the past.

We’re already seeing it, in fact. Museum-going in the United States overall seems to be fairly healthy. For the past three years, the 242 museums affiliated with the Association of Art Museum Directors attracted more than 60 million visits annually. National Endowment for the Arts surveys indicate that, in 2015, 19 per cent of adults attended an art exhibition at a museum or gallery.

But then there is this more pertinent number: between 2007 and 2015, nearly half the special exhibitions at the major museums in the US were devoted to art created after 1970, according to The Art Newspaper, which annually tabulates the subjects of, and attendance at, special exhibitions. And it is special exhibitions, not permanent collections, that draw most visitors to museums.

‘Just 20 years ago,’ the paper said, ‘Impressionism was king; no contemporary shows cracked the top ten most visited exhibitions in US museums in our 1997 attendance figures survey. Back then, only around 20 per cent of the shows organised by US institutions were devoted to the art of their time.’ Last year, seven of the top ten concerned contemporary art, by the paper’s measure, which ranks by average daily attendance rather than total attendance. (Using gross attendance figures, four of the top ten were contemporary; four were modern art; just two were pre-20th century.)

The research, which was conducted with the National Center for Arts Research at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, also came to a starker conclusion: museums that organise contemporary art exhibitions attract more people per exhibition than those presenting ‘balanced’ programming that includes exhibits of historic art.

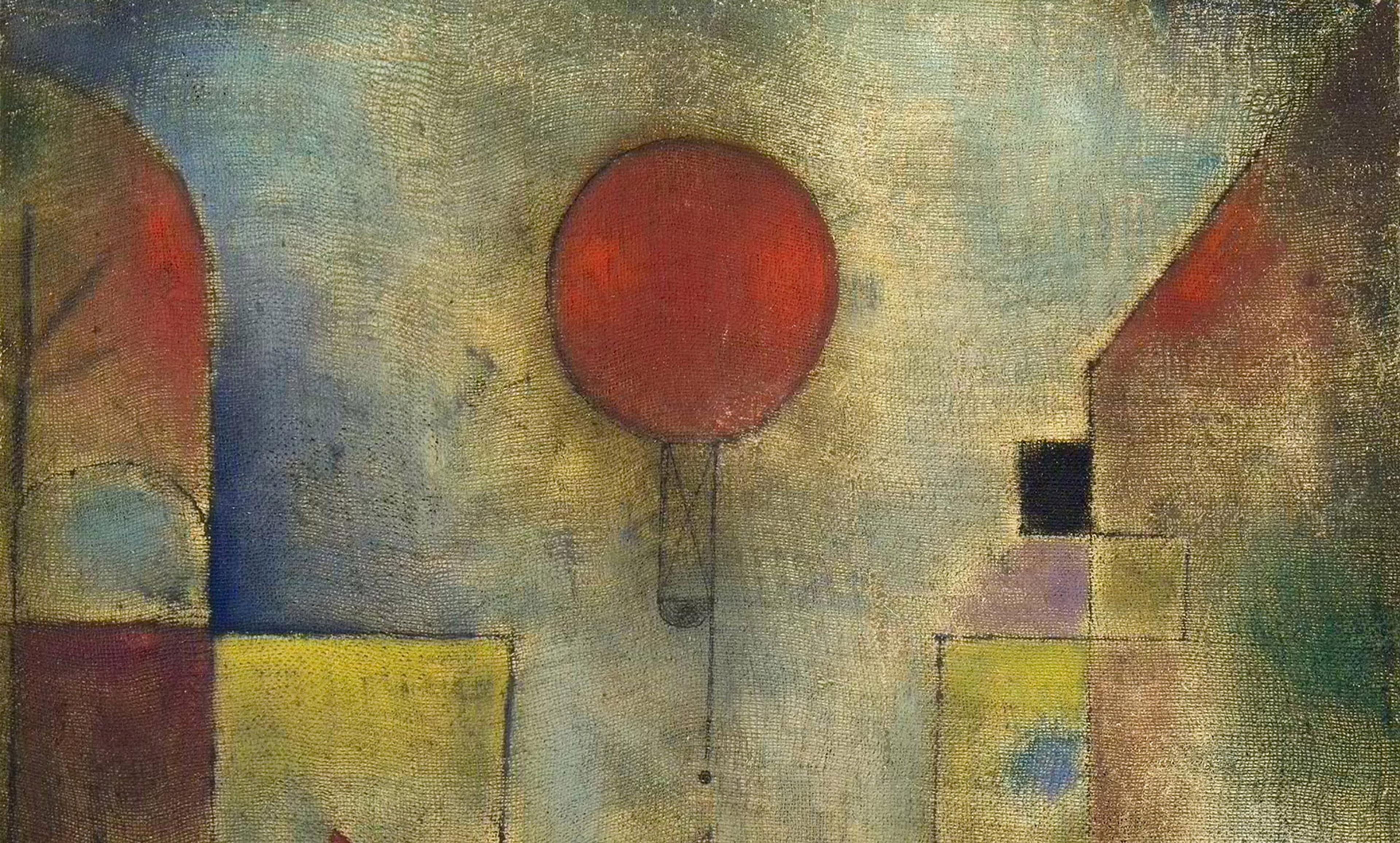

In this environment, with museum directors under pressure to boost attendance, Holbein loses out to Damien Hirst, Manet to Christian Marclay, Braque to Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Klee to Jeff Koons. Even museums whose collections extend back to the ancients are stressing contemporary art. In the past few years, some museum directors and fundraisers have told me that it has become difficult to find money for exhibitions displaying what some are now calling ‘pre-contemporary art’. Sponsors, be they corporations, foundations or individuals, are simply uninterested.

This is, as one art dealer remarked to me, like losing Mozart.

Or would be, if Mozart were being shunted aside by, say, Du Yun or Henry Threadgill, the two most recent winners of the Pulitzer Prize in music. But he isn’t. At the opera, Mozart, Verdi and Puccini still reign, while works by living composers are tough sells. Dance companies sell out performances of Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker and Swan Lake, but beg for audiences for contemporary dance programmes. The symphony halls of the US are crowded when classical geniuses such as Beethoven are on the programme, but sit half-empty when contemporary classical music is played. A bass player at a large symphony orchestra recently told me that fellow musicians refer to a common programming ploy – a contemporary work played between two popular classical compositions – as a ‘shit sandwich’.

Those disciplines are having their own audience problems, of course. Perhaps the most popular programmes in US concert halls are those offering movie themes, video-game music and the like – music that appeals to younger generations. Core audiences – those who love Mozart and his ilk – are greying, even as orchestras and opera companies strive to bring them to newer classical music.

That’s almost the opposite of what is happening in the visual arts, where curators and directors struggle to make ‘old art’ seem ‘relevant’, whatever that means, but contemporary art gets a pass on that score because it is made in the present. According to conventional wisdom, contemporary art is more ‘accessible’ to the public, though even some museum directors admit that mischaracterises the situation. Rather, contemporary art seems more accessible because curators are loath to ascribe meaning to an art work. Their labels fall back instead on describing physical properties and processes, and viewers are supposed to find their own meaning.

This ambiguity – that art can mean anything a viewer wants, or nothing at all – makes contemporary art more appealing to wider audiences. There is no need to learn the history, the characters or the symbols that artists of old portrayed and employed in their works. And therefore no reason to feel deficient.

Along with this non-taxing easiness, there is an experience or spectacle aspect to some contemporary art that draws young people in particular. Think of Marina Abramovic’s The Artist is Present at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York in 2010, of Rain Room at MoMA in 2013 and at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art from 2015-17, and of Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Mirrors at the Hirshhorn Museum of Art in Washington this year. There, people waited in lines for hours to get 20 to 30 seconds inside each of many mirrored rooms. These tales beget media attention, which begets more visitors motivated by fear of missing out.

The soaring art market, inflated by record-setting prices for works by Andy Warhol, Koons and company, also contributes to this state of affairs. Those sales grab headlines, and Americans will follow to see what the fuss is about. That is how Gustav Klimt, Alberto Giacometti and a few other long-dead artists have moved into the realm of known names that draw visitors to museums. Everyone wants to see the Woman in Gold by Klimt that cost Ronald Lauder $135 million. But a great work by Holbein or Manet, one that could make the news, doesn’t come up for sale all that often.

There are other reasons why museums are displaying more contemporary art: it is collected by many of their trustees, who push (and will fund) exhibitions; it is made by a more diverse group of artists than that of the past, when women and people of colour were excluded from art circles and art history, which allows museums to correct a historical imbalance – a welcome move; and those exhibitions are often cheaper to mount. Graduate art history students, those who intend to be curators, also focus increasingly on contemporary art.

But when these factors combine to crowd out attention to some of the world’s greatest works of art, our knowledge of past civilisations is diminished. Knowing less about different times and places means our knowledge of human nature grows thinner, narrower. We become, in short, less sophisticated. And aside from squandering the pure pleasure of viewing something as aesthetically satisfying as, say, a masterpiece by Albrecht Altdorfer or Luis Meléndez – to name just two magnificent artists who should be better known – we forfeit a connection that should enrich the experience of contemporary art.

Whenever culture, writ large, contracts, everyone loses.