A Syrian refugee camp near Erbil. Photo by Mustafa Khayat/Flickr

Humanity has entered a new, more enlightened era, marked by a consensus on universal human rights. Human rights are now paramount. Mass atrocities will not be allowed. Sovereignty will no longer protect states that violate these standards. So say well-meaning advocates of human rights. Don’t believe them. Two decades have shown that plans to protect people from massacres are so rife with practical and political shortcomings that we might be better off discarding the ideal.

The best-known plan is ‘The Responsibility to Protect’ (R2P) doctrine. It warns governments slaughtering their citizens that they will be stopped, with military might if essential, and that sovereignty will no longer provide them with cover to act with impunity.

At its 2005 World Summit, the United Nations endorsed R2P. Nearly 200 states signed on. Many scholars, activists and NGOs are guided by the ‘responsibility to protect’ doctrine. They point to the 2005 UN endorsement as evidence that it has become a norm that is global and enforceable.

Unfortunately, these lofty claims have no basis in reality. To begin with, R2P cannot be enforced. States routinely sign grand human-rights treaties and declarations – and then do as they please. Think, for instance, of the highfalutin language in the UN Charter, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Genocide Convention, and the International Covenant of Economic and Social and Cultural Rights. The noble wording in these documents lends itself to many different interpretations. Knowing this, states duly affix their signatures, formally recognising provisions they have no intention of honouring. When they violate the terms, they can parse words or, because these documents lack enforcement provisions, resort to simple defiance. The lack of implementation mechanisms in human-rights agreements is scarcely an oversight. States simply will not sign them if they include specific and enforceable obligations.

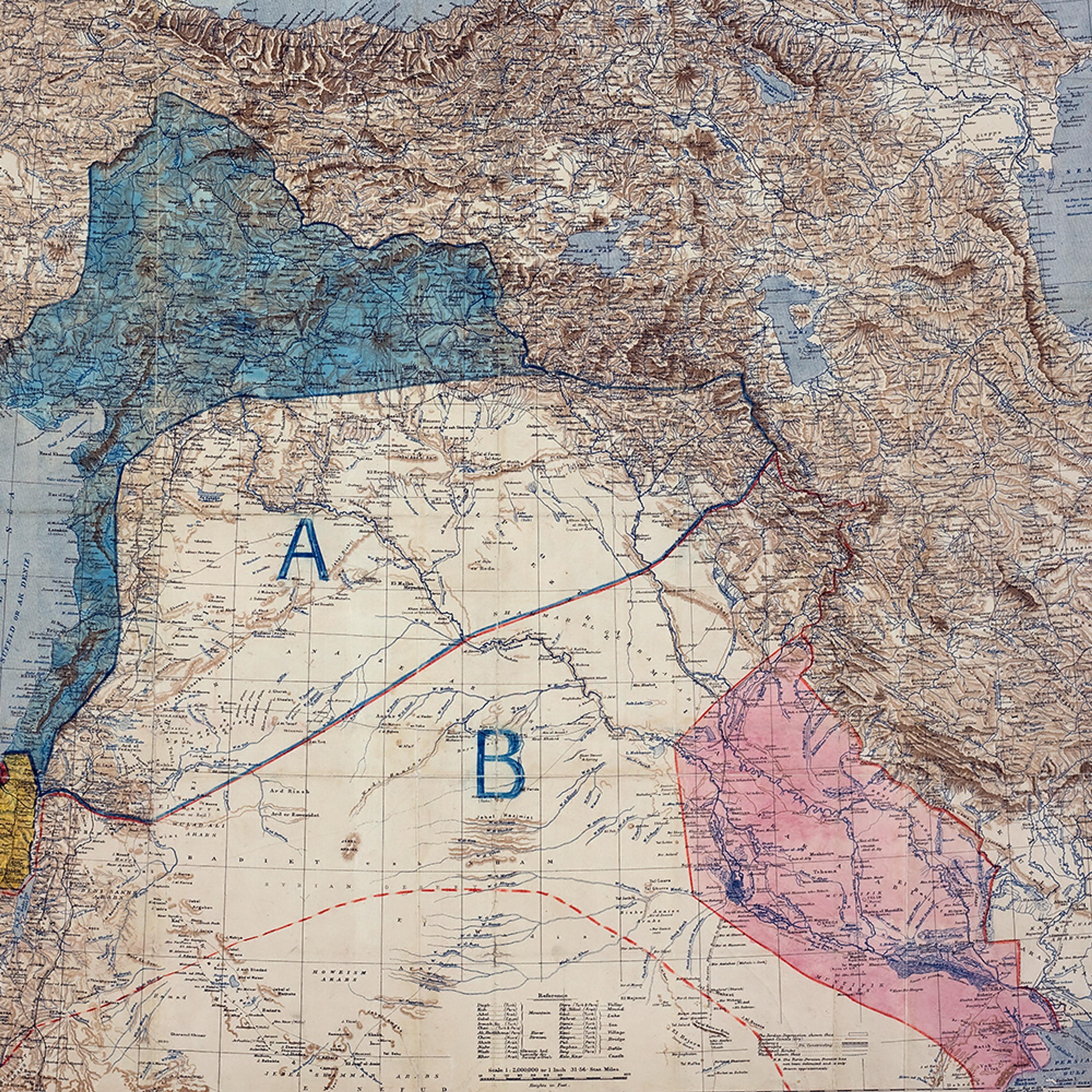

R2P suffers from this same gap between ideals and implementation. When the blood of innocents starts flowing somewhere, multiple barriers arise to implementing its provisions, not least the requirement for Security Council approval. A blood-soaked tyrant with a friend or two within the UN Security Council need not lose any sleep. Consider Omar al-Bashir of Sudan or Bashar al-Assad of Syria, or close US allies Saudi Arabia and Turkey who, in Yemen and in the Kurdish-majority regions respectively, are currently conducting airstrikes with little regard for non-combatants’ lives.

Mission creep is another flaw inherent in humanitarian intervention. A recent case in point: Security Council Resolution 1973 authorised the use of force in Libya to protect civilians under assault from Muammar Gaddafi’s army. The ensuing rescue operation quickly transmuted into a ‘regime change’ that is beginning to look like post-2003 Iraq. Consequently, it might well be both the first and the last UN-backed armed humanitarian intervention. After the Libya debacle, Brazil presented to the UN a proposed amendment to R2P, ‘Responsibility While Protecting’, which reflects the fears of smaller states that more powerful ones will invoke humanitarian ideals as a pretext to topple governments that they don’t like.

The 2011 Libya war also reveals another flaw of humanitarian intervention: hubris. Demolishing a rights-infringing regime is relatively easy; building even a semi-decent post-war order involves enormous challenges and resources. But without diligent, long-term state building and economic reconstruction, there can be no effective human rights, and humanitarian intervention will resemble a wrecking operation.

This is the lesson offered by post-intervention Libya, which has become an arena for bloodletting. Fighting rages among freewheeling militias and between two governments, each claiming to have the sole legitimate right to rule. Amid the mayhem, ISIS and criminal syndicates have established franchises. Neighbouring powers with irreconcilable agendas are arming their gun-toting clients. Libya might not survive as a unified state. The most vulnerable Libyans will suffer the most if it does collapse. And the Maghreb, already ravaged by terrorism and Islamic extremism because of the fallout from Libya, will become an even more dangerous place.

Finally, pace its boosters, humanitarian intervention lacks strong public support in the Western democracies that will necessarily be its main spear-carriers. Opinion polls confirm that only a minority of the Western public favours armed humanitarian interventions because of the fear that they could become messy and bloody. Not surprisingly, there have been no demonstrations on European and American streets demanding intervention in Syria.

American and European leaders understand this leeriness about armed humanitarian interventions full well. That’s why the interventions in Bosnia, Kosovo and Libya relied on high-altitude airpower. This style of intervention all but assures a zero death toll for intervening forces. But it also prolongs the war and thus provides perpetrators time to kill more and kill faster – precisely what happened in Kosovo and Libya.

Granted, armed intervention represents a big step; but sadly, Western governments have failed to deliver even on the much less demanding forms of support for the universal human rights they tout. Today, with a few exceptions, they are scrambling to keep out refugees fleeing the killing fields of Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan, having already failed to fund the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) adequately. Overburdened by having to feed and shelter several millions of people fleeing violence and war, UNHCR issues plaintive appeals for funding and has periodically been forced to cut back on essential supplies for Syrian refugees, who number 4 million and counting.

For these reasons, the prospects of a humanitarian intervention plan with universal legitimacy, a minimal amount of consistency, and robust procedures for implementation and for building a just post-war order are minimal. Yes, we will see interventions here and there of the usual sort; but when the rescuers resort to the blunt instrument of military force, prepare for more Libyas.