Kent Wang/Flickr

As a Brit with both working‑class and immigrant roots, there are two words on an invitation that I dread reading even more than ‘fancy dress’. They are ‘black tie’ – or what Americans would call a ‘tuxedo’. The costume party can be easily missed, but when instructed to turn up in a dinner jacket it’s usually because the host is an august institution whose favour you do not reject lightly.

I don’t like wearing ties at any time, and one of the advantages of my freelance life is that I can forgo the straightjacket of the business suit and work in my pyjamas instead. But my unease with black tie is not just about personal sartorial preferences. What really riles me is that, like most dress codes worldwide, the evening suit is a symbol of elitism and exclusion. When people are required to put on special dress, you don’t need to be an anthropologist to recognise that it is designed to emphasise the difference in status between those who wear it and those who do not.

My irritation might seem eccentric but I am in good company. Until he became the UK’s prime minister in 2007, Gordon Brown had spent years as Chancellor of the Exchequer refusing to wear the traditional white tie at events such his annual Mansion House speech. His critics charged Brown with engaging in a childish political gesture, and defended the dress code as a harmless, charming tradition.

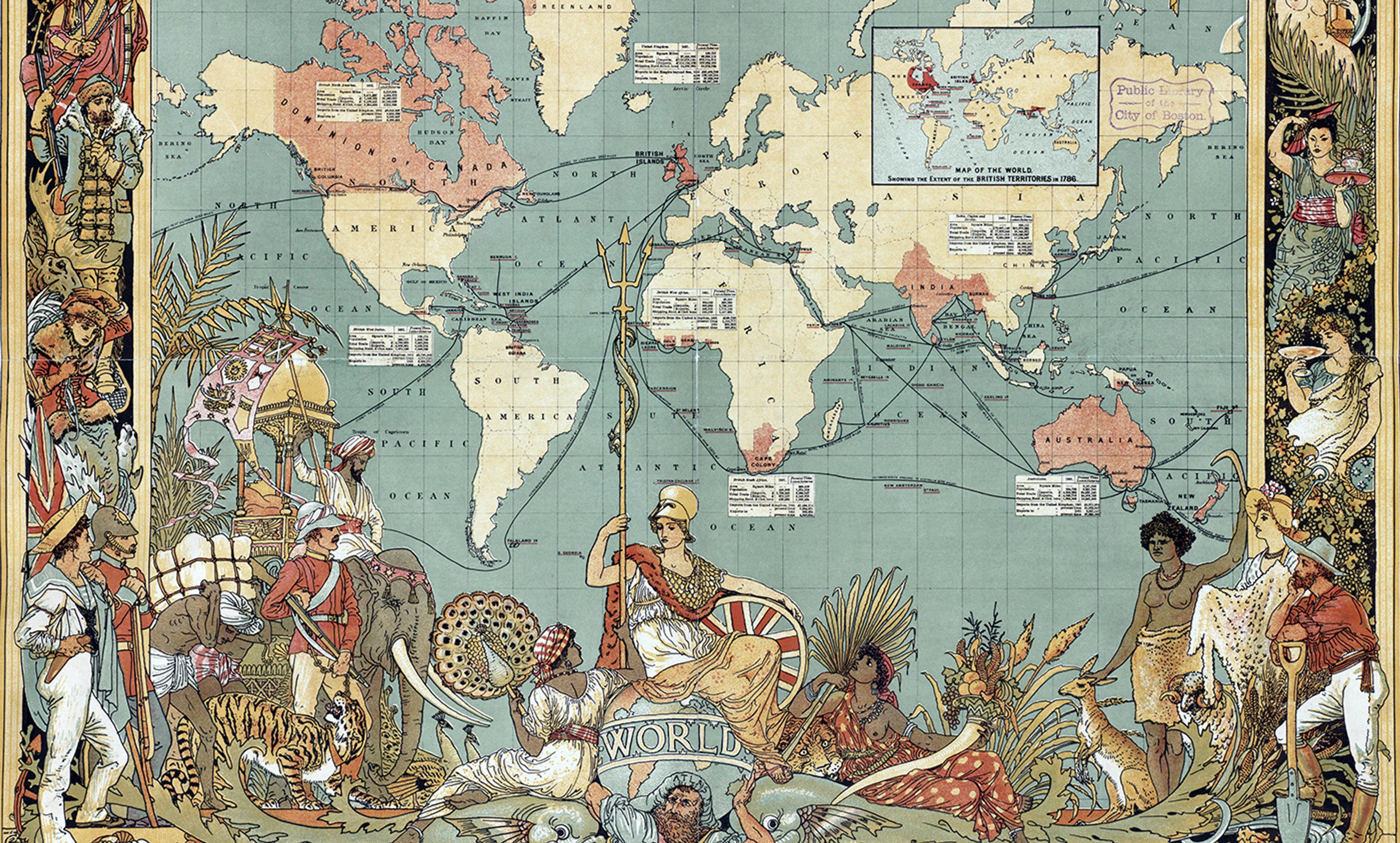

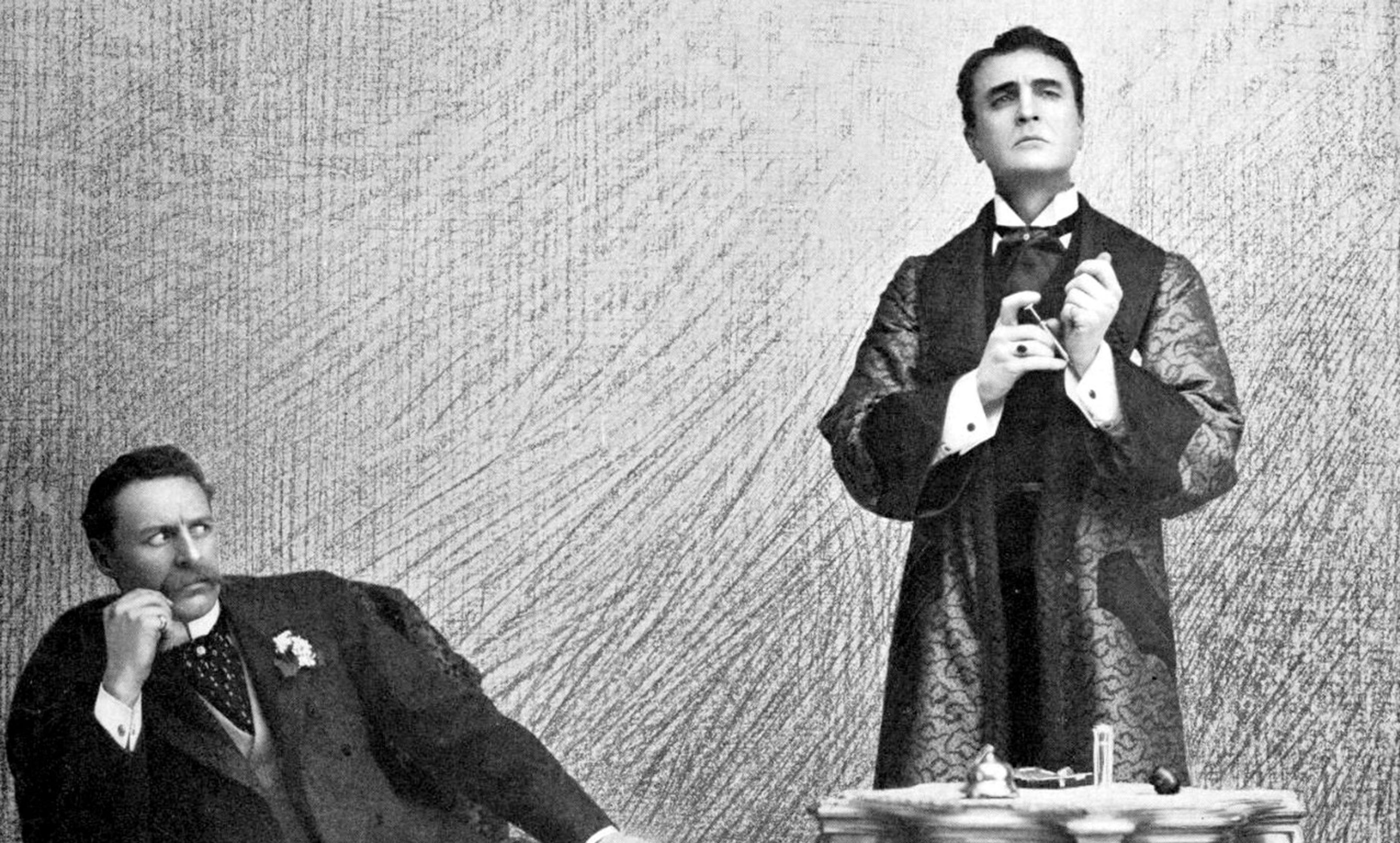

Not all traditions are charming or harmless. Sometimes they are not even especially traditional. Formal evening wear for men has been continually reinvented since the 18th century. Between the 1850s and the end of the 19th century, aristocrats and gentlemen dressed for dinner in a tailcoat with a wingtip collar and white tie. When the shorter dinner jacket was introduced in Victorian Britain, it was a somewhat outré informal alternative to wearing tails. It was considered far too daring for mixed company, and became standard formal wear only after the First World War. Even in the 1950s, the American etiquette expert Amy Vanderbilt declared the tuxedo an ‘essentially frivolous garment’ that ought never to be worn in a church.

In the UK, however, the dress code of black tie still evokes the habit of dressing for dinner in an aristocratic country house. Those who are perfectly at ease in black tie have usually been acculturated by the balls and formal dinners of elite universities, and they cannot possibly understand what it means to an outsider to be required to imitate them. To them, the idea of not having an evening suit in their wardrobes is as odd as it would be for me to own one. Even if I wore the most stylish evening suit possible, I would still be uncomfortable: I would feel as if I were wearing an actor’s costume, pretending to be someone I am not.

That is how formal dress codes work: they require the person who doesn’t have the right clothes either to turn up defiantly without them and stand out like a sore thumb, or to spend money buying or renting clothes in order to fit in, however awkwardly. Most would rather pay the financial rather than the social penalty.

Plenty of people who didn’t grow up in a world of balls and gowns gladly don evening dress when asked in order to integrate themselves into this elite world. Brown eventually put on the more formal white tie for a dinner with the Queen. In October, even Jeremy Corbyn, the leader of the UK Labour Party, sacrificed some of his socialist firebrand credentials by turning up to a dinner at Buckingham Palace in white tie. I don’t blame either of them for conforming in unique circumstances. But to me, when others roll over and conform too easily, that means colluding with structures of exclusive privilege. The tie that binds is also a uniform that alienates many others.

Refusing to wear black tie isn’t simply a matter of asserting one’s own ‘authentic’ individuality against the pressure to subsume that identity within a group. It’s more complicated than that. Even in ordinary dress, people are judged because of their accents, their names or where they were educated. When we are made acutely aware of class and privilege, we are also made aware of how our own identities are not simply the product of our own free choices and will. We cannot escape our histories, especially in cultures where people are so finely attuned to the markers of class.

For me, the intolerable tension created by the demand to wear black tie is that it forces me to observe the conventions of a class that I can never really join. If I refuse, it is not so much an egocentric assertion of my own uniqueness, but an acceptance that I cannot change who I am simply by following a new etiquette. And to those who want me to do just that, it is a reminder that their world is simply theirs – a tiny elite world, and not the world of everybody else, including me.