Children have a lot of learning to do. Arguably, this is the purpose of childhood: to provide children with protected time so that they can focus on learning how to communicate, how the world around them works, what values their culture finds important, and so on. Given the massive amount of information that children need to absorb, it would seem prudent for them to spend as much of this protected time as possible engaged in the serious study of real-world issues and problems.

Yet anyone who has spent time around young children knows that they hardly look like a set of serious, focused scholars. Instead, children spend a lot of their time singing songs, running around, and making a mess – that is, playing. Not only do they take great joy in uncovering the structure of reality through their exploratory play, children (like many adults) also tend to be deeply attracted to unrealistic games and stories. They pretend to have magical, superhero powers, and imagine interactions with impossible beings such as mermaids and dragons.

For a long time, both parents and researchers assumed that these flights of fancy were, at best, harmless episodes of fun – perhaps necessary to let off a little steam now and then, but with no real purpose. At worst, some have argued that these were dangerous distractions from the important task of understanding the real world, or manifestations of an unhealthy confusion about the barrier between reality and fiction. But new work in developmental science shows that not only are children perfectly capable of separating reality from fiction, but also that an attraction to fantastical scenarios might actually be helpful to their learning.

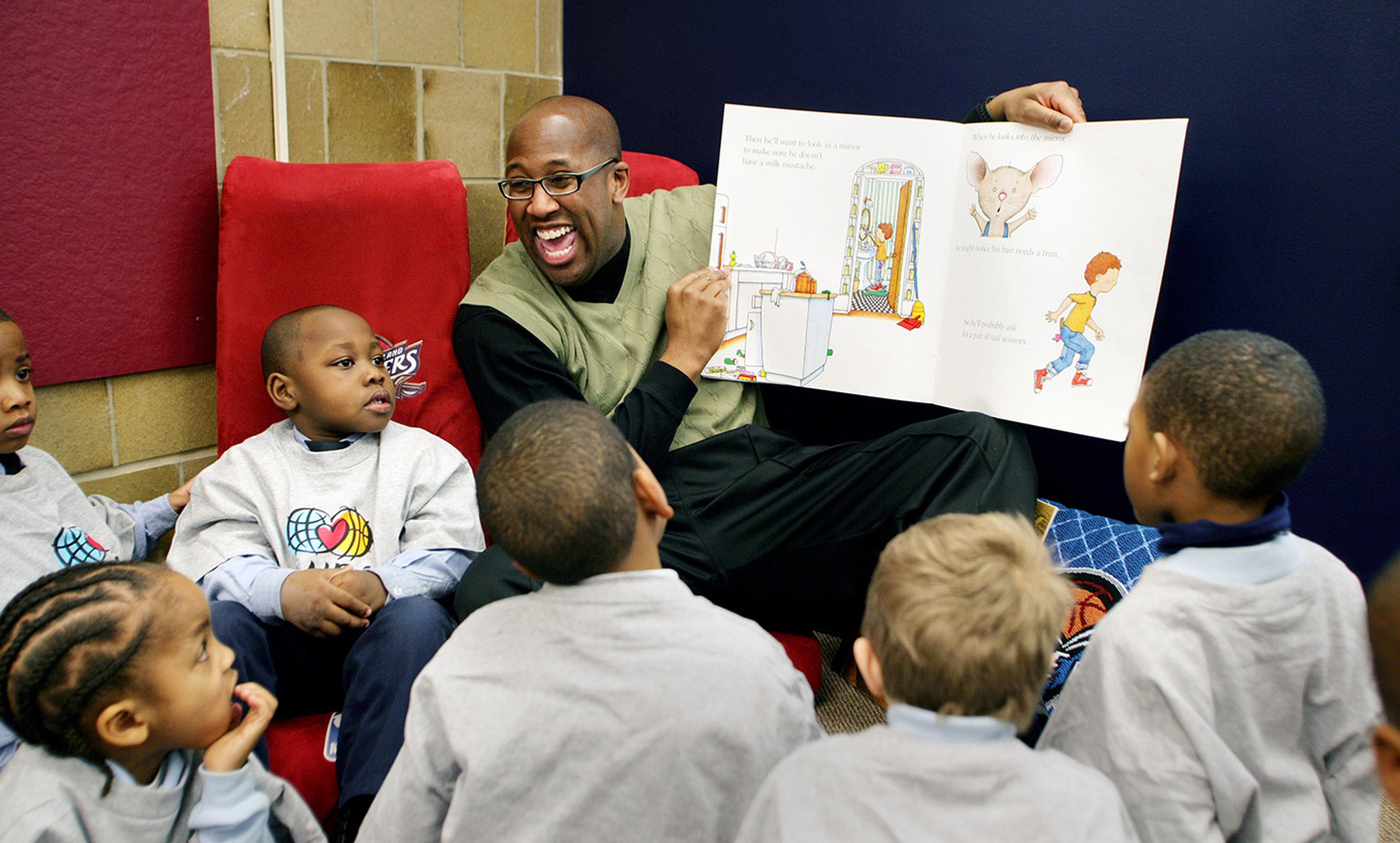

I arrived at this perspective after testing ways of teaching new words of vocabulary to preschoolers in the Head Start programmes, in hopes of combating the language deficit that exists between children from high and low socioeconomic backgrounds. To do the study, my team presented new words of vocabulary in the course of a shared book-reading activity, and then further reinforced the meanings of these words in adult-guided play sessions.

The intervention succeeded, and children’s understanding of the new words improved between pre- and post-test. But what was most interesting to us was the difference between two groups of children in this study: those whose stories described realistic themes, such as cooking, and those whose stories described fantastical themes, such as dragons. At the start of the study, published in 2015 in Cognitive Development, children knew less about words from the fantastical books, perhaps because these words were somewhat more challenging. But we found that children’s lexical knowledge caught up over the course of the intervention and, at the post-test, they knew as much about these words as they did about the words from the realistic stories. That is, children gained more knowledge from the fantastical stories than from the realistic ones.

This finding is surprising, since it flies in the face of everything we know about learning and transfer. A large body of literature in psychology has shown that the more similar the learning context is to the context where the information is eventually going to be applied, the better. This strongly suggests that the realistic books should have helped children learn the meanings of words better and report them more accurately on the post-test. But our study showed exactly the opposite: the fantasy books, the ones that were less similar to reality, allowed children to learn more.

In more recent work, our lab has been replicating the effect. One ongoing study is finding that children learn new facts about animals better from fantastical stories than from realistic ones. Other researchers, using a variety of methods and measures, have shown that representations of seemingly impossible events can help children’s learning. For example, infants are more prepared to accept new information when they are surprised, thus violating their assumptions about the physical world.

What can be going on? Perhaps children are more engaged and attentive when they see events that challenge their understanding of how reality works. After all, the events in these fantastical stories aren’t things that children can see every day. So they might pay more attention, leading them to learn more.

A different, and richer, possibility is that there’s something about fantastical contexts that is particularly helpful for learning. From this perspective, fantastical fiction might do something more than hold children’s interest better than realistic fiction. Rather, immersion in a scenario where they need to think about impossible events might engage children’s deeper processing, precisely because they can’t treat these scenarios as they would every other scenario that they encounter in reality.

They must consider every event with fresh eyes, asking whether it fits with the world of the story and whether it could fit within the laws of reality. This constant need to evaluate a story might make these situations particularly ripe for learning.

Future work will investigate all of these possibilities but, for now, it’s important to note that our findings could have profound implications for education. Even if it’s ‘only’ the case that children learn better in fantasy contexts because these contexts help them to pay better attention, we can leverage that fact to help make better instructional materials to benefit all children.