Aeon

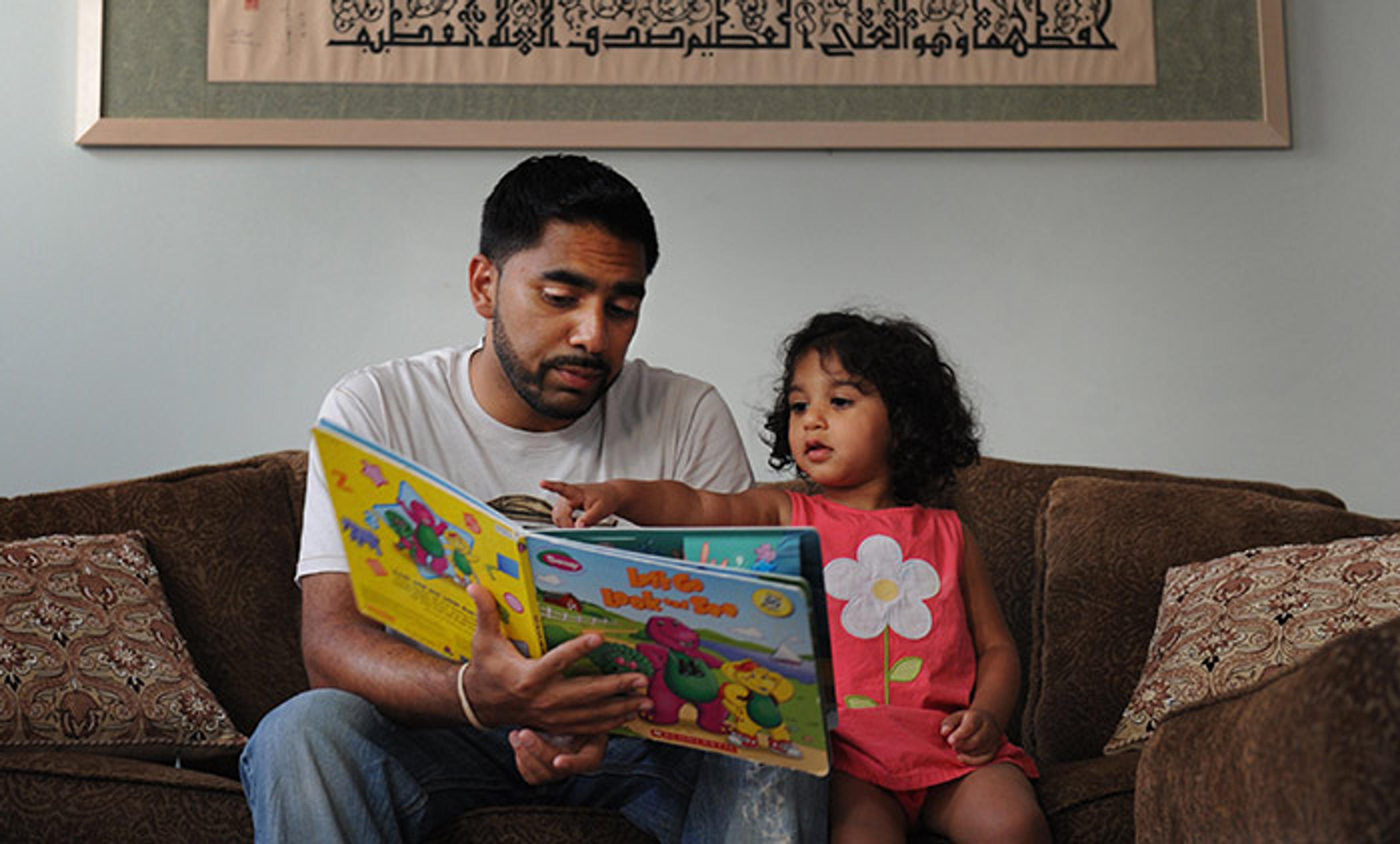

Imagine how an infant, looking out from her crib or her father’s arms, might see the world. Does she experience a kaleidoscope of shadowy figures looming in and out of focus, and a melange of sounds wafting in and out of hearing?

In his Principles of Psychology (1890), William James imagined the infant’s world as ‘one great blooming, buzzing confusion’. But today, we know that even very young infants have already begun to make sense of their world. They integrate sights and sounds, recognise the people who care for them, and even expect that people and other animate objects – but not inert objects – can move on their own.

Very young infants also tune in to the natural melodies carried in the lilting stream of language. These melodies are especially compelling in ‘motherese’, the singsong patterns that we tend to adopt spontaneously when we speak to infants and young children. Gradually, as infants begin to tease out distinct words and phrases, they tune in not only to the melody, but also to the meaning of the message.

Once infants utter their first words, typically at around their first birthdays, we can be sure that they have begun to harness the sounds of language to meaning. In my own family, after nearly a year of guessing what my daughters’ babbles might mean, their first words – datoo (bottle), Gaja (Roger, a beloved dog), uppie (a plea for someone to pick her up) – assured me, in a heartbeat, that they do speak my language!

In all cultures, babies’ first words are greeted with special joy. This joy is testimony to the power of language – a signature of our species and our most powerful cultural and cognitive convention. Language permits us to share the contents of our hearts and minds, in ways that are unparalleled elsewhere in the animal kingdom. It is the conduit through which we learn from and about others, across generations and across cultures.

But how, and when, do infants begin to link language to meaning?

We know that the path of language acquisition begins long before infants charm us with their first words. From the beginning, infants are listening, and they clearly prefer some sounds over others. How could we possibly know this? Newborn infants can’t point to what they like or crawl away from what they don’t. But when infants’ interest is captured by a particular sight or sound, they will suck rapidly and vigorously on a pacifier.

Using rates of sucking as a metric, infancy researchers have discovered that, at birth, infants prefer hearing the vocalisations of humans and non-human primates. Then, within months, they narrow their preference specifically to human vocalisations. And toward the end of their first year, infants become ‘native listeners’, homing in with increasing precision on the particular sounds of their own native language.

So, the early preference of newborns for listening to language sets the stage for them to zero in on their own native language sounds and to discover its words and syntax. But only recently did we discover that listening to language benefits more than language acquisition alone. It also boosts infants’ cognition.

It might be difficult to imagine how we discovered the influence of language on infant cognition, especially in tiny infants who respond only in gurgles, giggles and rates of sucking. Fortunately, developmental psychologists have a talent for distilling such complex questions down to their essences. To discover the power of language on infant cognition, my colleagues and I began by focusing on one especially powerful building block of cognition known as object categorisation. We asked whether and how infants link language to this core cognitive capacity.

To form an object category such as dog, an infant must somehow notice that, despite their differences, different individuals – perhaps her own dog, Magic, and a neighbour’s dog, Fido – have a lot in common: they are members of the same category. Once they have detected this category, and even before they have learned the word dog, infants can use it spontaneously, just like we do, to make educated guesses about all dogs, including ones they’ve never seen. Imagine, for instance, an infant who has already learned, by observing Magic and Fido, that when a dog is pulled by its tail, it’s likely to growl or snap back angrily. Armed with such categories, an infant can make inferences about new dogs, even before she begins to play with them.

In other words, when we form object categories, we streamline our subsequent learning.

We can now turn to the question at hand: do infants link language and object categories? To address this, with my colleagues Alissa Ferry and Sue Hespos, we invited three- and four-month-old infants and their parents to visit our lab at Northwestern University in Illinois. Once infants were settled in and seated comfortably on their parents’ laps, we showed them a series of different objects, all from the same object category, such as dinosaurs.

As they viewed these objects, half of the infants listened to human language; the others listened to a series of sine-wave tone sequences. We created these sequences so that they matched the language in pitch and duration; we also imposed pauses in exactly the same places as there were pauses in the language stimuli.

Next, we tested the infants’ categorisation. To do so, we showed them two new images: one was a new dinosaur that they hadn’t yet seen, and the other was a member of a new category, such as fish. Because these tiny infants cannot tell us what they think about the objects we showed them, we used infants’ eyes as windows into their thinking. We carefully analysed infants’ looking time at the two new objects.

Here is the logic: if infants successfully formed the object category dinosaur, then they should distinguish between the new dinosaur and the fish. And if listening to language offers them a cognitive boost, then infants who’d listened to language while they viewed the dinosaurs should be better able to notice the object category than infants who’d listened to sine-wave tone sequences.

Listening to human language had a powerful effect. Three- and four-month-olds listening to language successfully formed object categories; infants listening to the tone sequences did not. Thus, even before infants can roll over in their cribs, listening to language boosted their cognition.

Next, we wondered whether language alone offers this boost. To answer this question, we engaged another group of infants in the very same categorisation task, but with a twist. This time, infants listened to the vocalisations of a non-human primate, Eulemur macaco flavifrons – a Madagascan blue-eyed black lemur.

Infants’ responses to the lemur vocalisations were striking. At three and four months, listening to lemurs conferred precisely the same advantage as human language. Interestingly, although our infants had considerable exposure to human language, and very little, if any, to lemur calls, human and lemur vocalisations offered our youngest infants precisely the same cognitive advantage. This tells us that infants initially make a broad link between ‘language’ and cognition, one that includes vocalisations of both human and non-human primates, our closest genealogical cousins. But by six months, lemur calls no longer offered this cognitive advantage; only human language did the trick.

We also discovered that listening to language has more far-reaching effects, supporting not only infants’ categorisation and reasoning about objects, but also their social and communicative insights.

For example, one of the most complex problems that infants face is gaining insight into the minds of others. It turns out that infants’ headway in ‘mind reading’ is supported by language. By six months, infants appreciate the communicative status of speech, and view it as a conduit between minds, a channel through which we can share goals and intentions.

These glimpses into the infant mind illuminate the mystery of how infants forge a link between language and thought. They also give new meaning to the words of the poet Rita Mae Brown: ‘Language exerts a hidden power, like the tides on the Moon.’

Listening to language exerts its hidden power far earlier than even the most devoted parents, teachers or policy-makers could ever have imagined. Language is an elixir – and infants drink it in. It fuels the infant’s mind and catalyses her quintessentially human psychological capacities from the very beginning.